Chapter 6 Environmental and Social Assessment of Draft Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector Development Plan (Fasdp)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghana Gazette

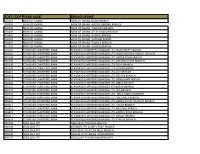

GHANA GAZETTE Published by Authority CONTENTS PAGE Facility with Long Term Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 1236 Facility with Provisional Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 201 Page | 1 HEALTH FACILITIES WITH LONG TERM LICENCE AS AT 12/01/2021 (ACCORDING TO THE HEALTH INSTITUTIONS AND FACILITIES ACT 829, 2011) TYPE OF PRACTITIONER DATE OF DATE NO NAME OF FACILITY TYPE OF FACILITY LICENCE REGION TOWN DISTRICT IN-CHARGE ISSUE EXPIRY DR. THOMAS PRIMUS 1 A1 HOSPITAL PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI KUMASI KUMASI METROPOLITAN KPADENOU 19 June 2019 18 June 2022 PROF. JOSEPH WOAHEN 2 ACADEMY CLINIC LIMITED CLINIC LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE MAMPONG KUMASI METROPOLITAN ACHEAMPONG 05 October 2018 04 October 2021 MADAM PAULINA 3 ADAB SAB MATERNITY HOME MATERNITY HOME LONG TERM ASHANTI BOHYEN KUMASI METRO NTOW SAKYIBEA 04 April 2018 03 April 2021 DR. BEN BLAY OFOSU- 4 ADIEBEBA HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG-TERM ASHANTI ADIEBEBA KUMASI METROPOLITAN BARKO 07 August 2019 06 August 2022 5 ADOM MMROSO MATERNITY HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI BROFOYEDU-KENYASI KWABRE MR. FELIX ATANGA 23 August 2018 22 August 2021 DR. EMMANUEL 6 AFARI COMMUNITY HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI AFARI ATWIMA NWABIAGYA MENSAH OSEI 04 January 2019 03 January 2022 AFRICAN DIASPORA CLINIC & MATERNITY MADAM PATRICIA 7 HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI ABIREM NEWTOWN KWABRE DISTRICT IJEOMA OGU 08 March 2019 07 March 2022 DR. JAMES K. BARNIE- 8 AGA HEALTH FOUNDATION PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI OBUASI OBUASI MUNICIPAL ASENSO 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 DR. JOSEPH YAW 9 AGAPE MEDICAL CENTRE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI EJISU EJISU JUABEN MUNICIPAL MANU 15 March 2019 14 March 2022 10 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION -ASOKORE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE KUMASI METROPOLITAN 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION HOSPITAL- DR. -

Vowel Height Agreement in Ewe

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research Volume 4, Issue 7, 2017, pp. 206-216 Available online at www.jallr.com ISSN: 2376-760X Vowel Height Agreement in Ewe Pascal Kpodo * University of Education, Winneba, Ghana Abstract This paper seeks to give a descriptive account of a vowel height feature agreement process in Ewe. The paper establishes that the height agreement process is neither height harmony nor metaphony. The paper further demonstrates the systematic difference between the coastal dialects and the inland dialects of Ewe in relation to the vowel height agreement process. The height agreement occurs in the cliticization of diminutive marker to nouns and adjectives as well as the cliticization of the 3rd person singular object pronominal to verbs. While the agreement process is host controlled in the inland (Ʋedome) dialects of Ewe, it is enclitic controlled in the coastal (Aŋlɔ) dialects of Ewe. A synchronic analysis indicates that while [i] is the underlying form of the enclitic for the 3rd person singular object pronominal as well as the diminutive marker in the coastal dialects of Ewe, [e] is the underlying representation of the 3rd person singular object pronominal as well as the diminutive marker in the inland dialects of Ewe. Keywords: clitic, enclitic, metaphony, feature agreement BACKGROUND The Ewe Language is a member of the Kwa sub-group of the Volta-Comoe branch of the Niger-Congo language family. Ewe is a member of the Gbe language cluster spoken within an area stretching from the southwestern corner of Nigeria, across southern Benin and Togo into the Volta Region of Ghana (Capo, 1985; Stewart, 1989, as cited in Kluge, 2000). -

Road Safety Review: Ghana Know Before You Go Driving Is on the Right

Association for Safe International Road Travel Road Safety Review: Ghana Know Before You Go Driving is on the right. Drivers are required to carry an International Driving Permit (IDP) or a Ghanian driving license; along with a passport or visa. An IDP must be obtained prior to arrival in Ghana. Keep passport and visa with you at all times; document theft from hotels is common. Pedestrians account for 46 percent of all road traffic fatalities. Riders of two- and three-wheeled motorized vehicles make up 18 percent of road crash deaths. Blood alcohol limit is below 0.08 g/dl for all drivers. Enforcement of drink driving laws is low. There are 24.9 road deaths per 100,000 people in Ghana, compared to 2.8 in Sweden and 3.1 in the UK. Driving Culture • Compliance with traffic rules and laws is low. • Aggressive driving and dangerous overtaking are typical. • Speed limit laws are poorly enforced. • Drivers may swerve suddenly into oncoming traffic to avoid potholes. Source: CIA Factbook • Drivers often speed and behave recklessly, including drivers of public transport. • Trotro minibus and minivan drivers are often untrained; reckless behavior among drivers is common. Trotro drivers commonly pull into traffic without signaling. • Pedestrians often walk along road edges or in road lanes, even in the dark. • There are many loose animals on roadways, particularly at dusk, dawn and during the night. • Drivers may place piles of leaves and/or grass in roadways to alert other motorists of a crash or hazard ahead. • Poorly maintained vehicles are common. Many vehicles lack standard safety features including seat belts, working brakes, adequate tires, headlights, tail lights, turn signals and windscreen wipers. -

Certified Electrical Wiring Professionals Volta Regional Register Certification No

CERTIFIED ELECTRICAL WIRING PROFESSIONALS VOLTA REGIONAL REGISTER CERTIFICATION NO. NAME PHONE NUMBER PLACE OF WORK PIN NUMBER CLASS 1 ABOTSI FELIX GBOMOSHOW 0246296692 DENU EC/CEWP1/06/18/0020 DOMESTIC 2 ACKUAYI JOSEPH DOTSE 0244114574 ANYAKO EC/CEWP1/12/14/0021 DOMESTIC 3 ADANU KWASHIE WISDOM 0245768361 DZODZE, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/06/16/0025 DOMESTIC 4 ADEVOR FRANCIS 0241658220 AVE-DAKPA EC/CEWP1/12/19/0013 DOMESTIC 5 ADISENU ADOLF QUARSHIE 0246627858 AGBOZUME EC/CEWP1/12/14/0039 DOMESTIC 6 ADJEI-DZIDE FRANKLIN ELENUJOR NOVA KING 0247928015 KPANDO, VOLTA EC/CEWP1/12/18/0025 DOMESTIC 7 ADOR AFEAFA 0246740864 SOGAKOPE EC/CEWP1/12/19/0018 DOMESTIC 8 ADZALI PAUL KOMLA 0245789340 TAFI MADOR EC/CEWP1/12/14/0054 DOMESTIC 9 ADZAMOA DIVINE MENSAH 0242769759 KRACHI EC/CEWP1/12/18/0031 DOMESTIC 10 ADZRAKU DODZI 0248682929 ALAVANYO EC/CEWP1/12/18/0033 DOMESTIC 11 AFADZINOO MIDAWO 0243650148 ANLO AFIADENYIGBA EC/CEWP1/06/14/0174 DOMESTIC 12 AFUTU BRIGHT 0245156375 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0035 DOMESTIC 13 AGBALENYO CHRISTIAN KOFI 0285167920 ANLOKODZI, HO EC/CEWP1/12/13/0024 DOMESTIC 14 AGBAVE KINDNESS JERRY 0505231782 AKATSI, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/12/15/0040 DOMESTIC 15 AGBAVOR SIMON 0243436475 KPANDO EC/CEWP1/12/16/0050 DOMESTIC 16 AGBAVOR VICTOR KWAKU 0244298648 AKATSI EC/CEWP1/06/14/0177 DOMESTIC 17 AGBEKO MICHEAL 0557912356 SOGAKOFE EC/CEWP1/06/19/0095 DOMESTIC 18 AGBEMADE SIMON 0244049157 DABALA, SOGAKOPE,VOLTA REGIONEC/CEWP1/12/16/0052 DOMESTIC 19 AGBEMAFLE MICHAEL 0248481385 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0038 DOMESTIC 20 AGBENORKU KWAKU EMMANUEL 0506820579 DABALA JUNCTION- SOGAKOPE, VOLEC/CEWP1/12/17/0053 DOMESTIC 21 AGBENYEFIA SENANU FRANCIS 0244937008 CENTRAL TONGU EC/CEWP1/06/17/0046 DOMESTIC 22 AGBODOVI K. -

University of G Institute of African Studies 3U C B

UNIVERSITY OF G INSTITUTE OF AFRICAN STUDIES 18 JUN1969 DEVEL0PMEN1 MUDIES "W 91/ 3 ) W O Jt. LIBRARY 3UCBAJ IS TER 1966 UNIVERSITY OF GHANA INSTITUTE OF AFRICAN STUDIES RESEARCH REVIEW VOL. 3 NO.1 MICHAELMAS TERM 1966 RESEARCH REVIEW CONTENTS INSTITUTE NEWS Staff......................... • • • p. 1 LONG ARTICLE African Studies in Germany, Past and Present.................... p. 2 PRO JECT REPORTS The Ashanti Research Project................ P*|9 Arabic Manuscripts........... ............. .................................. p .19 INDIVIDUAL RESEARCH REPORTS A Study in Urbanization - Progress report on Obuasi Project.................................................................... p.42 A Profile on Music and movement in the Volta Region Part I . ............................................. ........................ p.48 Choreography and the African Dance. ........................ p .53 LIBRARY AND MUSEUM REPORTS Seminar Papers by M .A . Students. .................. p .60 Draft Papers................................................... ........ p .60 Books donated to the Institute of African Studies............. p .61 Pottery..................................................................... p. 63 NOTES A note on a Royal Genealogy............................... .......... p .71 A note on Ancestor Cult in Ghana ................. p .74 Birth rites of the Akans ..................................... p.78 The Gomoa Otsew Trumpet Set........... ............. ............. p.82 ******** THE REVIEW The regular inflow of letters from readers -

Sdlao Uemoa Uicn

0° 1° E 2° E Kouffo Sakété Adjohoun ! ! Mono Lokossa Allada ! ! Haho Athiémè Tagbligbo ! Dangbo ! Bopa ! ! Akpro-MissérétéAvrankou ! ! Adjara ! Zio BENIN Foret d'Eto Sè Tori-Bossito ! ! Porto-Novo Lac Ahémé Lac ! ! Ganvié Akodéha.! Abomey-Calavi! .! ! ! Aguégué Kpomasse ! ! Tohouè Vo Ativé Zooti Lac Nokoué Djérèbé! Tsevie ! ! Kétonou ! Kevé ! Atitogon ! ! ! Comé Agatogbo! ! ! Agbanto Ekpé Kpodji-Agué TOGO Akoumapé ! Vo Afouinmé ! ! ! ! Kraké !Sèmè-Kpodji! Hahatoé Vo Koutimé Ouidah ! ! Gbéhoué ! ! Avlékété Aklakou ! ·[ Vogan Anfoin ! ! ! Djégbadji ! COTONOU k Ganavé Djondji h Sevagan ! ! ! Wogba Avlo ! ! Zones Humides du Littoral du Togo Noépé ! ! Djablé .! Akoda ! Agoué Aképé ! ! Grand-Popo Dzodze ! ! Togoville ! ! ! Volta Lebe ! Gbodjomé ! Aného ! ! h Agbodrafo Kpong ·[ ! h k LOME ! Denu Aflao Akatsi ! ! Adiome ! Sogakope Tsiame ! ! Anyako Dabala ! 7° N ! 7° N Atiavi Keta Lagoon ! GHANA Kasseh .! [ ! ! Keta k Songaw Lagoon ! Oyibi .! ! Lekpoguno Lolonya ! ! Palm Point Anloga ! ! ! Dzita ! Old Ningo ! Ada-Foah Strogboe New Ningo ! k ! k ! Prampram ! Grove Point Tema k Bontrase h ! ·[ Asafo ! Oduponkpehé Swedru ! k ! Accra Point Afranse Bortianor .! k ! ! Densu ACCRA k delta ! Nyanyano Buduburam ! Feté ! Awutu Senya k Beraku Point ! Winneba ! Muni .! Winneba Point Lagoon k Apam Apam Point ! k REGIONAL SHORELINE MONITORING STUDY AND ! Mumford DRAWING UP A MANAGEMENT SCHEME FOR Babli Point ! !Akra THE WEST AFRICAN COASTAL AREA Tantum Country borders TYPOLOGY OF HUMAN LAND-USE SYSTEMS LESS THAN 1KM FROM SHORE ROAD NETWORK West African Major -

The Ghanaian Dug-Out Canoe and the Canoe Carving Industry in Ghana

FAO LIBRARY AN: 314915 rIDAF/WP / 35 Mare.h1991 THE GHANAIAN DUG OUT CANOE AND THE CANOE CARVING INDUSTRY IN GHANA PAO/OLIOk 941 1 01 ISINFEWWPAT IDAF/WP/35 March 1991 THE GHANAIAN DUG-OUT CANOE AND THE CANOE CARVING INDUS1RY IN GHANA G.T. Sheves ProgrammedeDéveloppement Intégré des Péches Artisanales en Afrique de l'Ouest - DIPA ProgrammeforIntegrated DevelopmentofArtisanal Fisheries in West Africa - IDAF GCP/RAF/192/DEN With financial assistance from Denmark and in collaboration with the Republic of Benin, the Fisheries Department of FAO is implementing in West Africa a programme of small scale fisheries development, commonly called the IDAF Project. This programme is based upon an integrated approach involving production, processing and marketing of fish, and related activities ; it also involvesan active participation of the target fishing communities. This report isa working paper and the conclusions and recommendations are those considered appropriate at the time of preparation. The working papers have not necessarily been cleared for publication by the government (s) concerned nor by FAO. They may be modified in the light of further knowledge gained at subsequentstages ofthe Project and issued laterin other series. The designations employed and the presentation of material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of FAO or a financing agency concerning the legal status of any country or territory, city or area, or concerning the determination of its frontiers or boundaries. IDAF Project FAO Boite Postale 1369 Cotonou, R. Benin Télex : 5291 FOODAGRI Tél. 330925/330624 Fax : (229) 313649 Dr. Gordon Sheves was CTA of the Model Project Benin from 1984 to 1989. -

Northern Volta Ashanti Brong Ahafo Western Eastern Upper West

GWCL/AVRL Systems, Service Areas and Towns and Cities Served *# (!BAWKU BAWKU *# Legend Legend (! Upper East Water use in GWCL/AVRL Service Areas (AVRL 2007) NAVRONGO *#!(*# GWCL/AVRL system (AVRL 2007) NAVRONGO Upp(!er East Design plant capacity BOLGATANGA *# < 2000 m^3/day *# 2000 - 5000 m^3/day water use, tanker 5000 - 10000 m^3/day *# water use, domestic connection Upper West water use, commercial connections Upper West *# 10000 - 50000 m^3/day water use, industrial connections water use, industrial connections > 50000 m^3/day *# water use, sachet producers *# water use, unmetered standpipes Served town / city (!WA WA water use, metered standpipes Population (GSS 2000) Main road !( 1000 - 5000 Water body (! 5001 - 15,000 Region *# (! 15,001 - 30,000 !*# (! 30,001 - 50,000 (YENDI Northern YENDI TAMALE Norther(!nTAMALE (!50,001 - 100,000 (!*# DAMONGO (!> 100,000 Link between system and served town Main road Water body Region Brong Ahafo Brong Ahafo *# *# *# *# (!TECHIMAN (! TECHIMAN WORAWORA ! (!*# (BEREKUM *# JASIKAN BEREKUM (!SUNYANI Volta SUNYANI Volta !(*# *# DWOMMO !(*# *# NKONYA AHENKRO! HOHOE (HOHOE (! DWOMMO BIASO *# *# BIASO *# (! M(!AMPONG *# !( TEPA # (!*# MAMPONG ACHERENSUA * !( KPANDU (! SO*#VIE KPANDU AGONA !( TEPA (!*# ANFOEGA DZANA (!*# ACHERENSUA *# (!ASOKORE KPEDZE As*#hanti *# Ashanti *# KUMASI (!KUMASI (! KONONGO *# *# *# *# (! (!HO KONONGO HO ! !( TSITO Eastern N(KAWKAW ANUM NKAWKAW *# *# E(!a*#stern ANYINAM !( (! (! OSINOBEGORO *# KWABENG *#!( *# (! BUNSO *# (! ASUOM JUAPONG *# *#*# (! NEW TAFO # !( # NEW TAFO * -

2003 National Industrial Censu

GHANA STATISTICAL SERVICE AUGUST, 2011 PART A: YOUR ROLE AS A SUPERVISOR 1. Your Status in the MICS4 As a field supervisor, you play a vital role in the survey field operations. You are the mediator between the Field Interviewers who are collecting the required information and the MICS4 Survey Secretariat. The chart below shows your position in the survey organisation. SECRETARIAT FIELD SUPERVISOR FIELD INTERVIEWER As a Field Supervisor, you will work with three (3) Field Interviewers, One (1) Field Editor, One (1) Health Technician (for the Malaria Biomarker component of the survey) and a Driver. 2. Your main task in the survey You are required to supervise a number of interviewers who will work directly under you during the field work. During the period, interviewers are to interview selected households and some members of these households by administering four (4) different questionnaires –The Household Questionnaire, the Women’s Questionnaire, the Questionnaire for Children Under Five and the Men’s Questionnaire. To ensure good quality data from the field, it is your duty to see that interviewers carry out this assignment efficiently. To achieve this: a. You must master the interviewer’s manual The Interviewer’s manual contains detailed information about the survey as well as instructions showing how interviewers should go about the field work. You can supervise effectively only if you yourself understand very clearly what the interviewers are being asked to do. This means that you have to read the interviewer’s manual several times and get a clear understanding of what their work entails before starting your supervisory work. -

Sort Code Bank Name Branch Name

SORT CODE BANK NAME BRANCH NAME 010101 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA ACCRA BRANCH 010303 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -AGONA SWEDRU BRANCH 010401 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -TAKORADI BRANCH 010402 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -SEFWI BOAKO BRANCH 010601 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -KUMASI BRANCH 010701 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -SUNYANI BRANCH 010801 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -TAMALE BRANCH 011101 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA - HOHOE BRANCH 020101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-HIGH STREET BRANCH 020102 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD- INDEPENDENCE AVENUE BRANCH 020104 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-LIBERIA ROAD BRANCH 020105 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-OPEIBEA HOUSE BRANCH 020106 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-TEMA BRANCH 020108 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-LEGON BRANCH 020112 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-OSU BRANCH 020118 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-SPINTEX BRANCH 020121 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-DANSOMAN BRANCH 020126 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-ABEKA BRANCH 020127 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH)-ACHIMOTA BRANCH 020129 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD- NIA BRANCH 020132 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD- TEMA HABOUR BRANCH 020133 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD- WESTHILLS BRANCH 020436 -

Tropenbos International Ghana's Footprint in the Forestry Sector

Tropenbos International Ghana’s footprint in the forestry sector Tropenbos International Ghana’s footprint in the forestry sector ii This publication is produced under the Tropenbos Ghana Programme with financial assistance from the Dutch Ministry for Development Cooperation. The contents of this publication can in no way be taken as the views of the Dutch Government. Published by: Tropenbos International Ghana Copyright: © Tropenbos International Ghana. Kumasi, Ghana Texts may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, citing the source. Citation: Bernice Agyekwena, Jane Aggrey and Samuel Nketiah (2016). Tropenbos International Ghana’s footprint in the forestry sector. Tropenbos International Ghana, Kumasi, Ghana. 51 pp Layout and design Jane Aggrey Photos: Tropenbos International Ghana Printed by: KATA Prints Limited, Kumasi Ghana Available from: Tropenbos International Ghana Samuel Kwabena Nketiah P. O. Box UP 982 KNUST Kumasi, Ghana Tel: +233 3220 0310/61361 Www.tropenbos.org iii Table of contents TBI Ghana pilots Wood Tracking System for the domestic market 15 Contributing to good forest governance Working together for domestic lumber supply 2 Knowledge on VPA shared with three west African countries 16 Supplying legal lumber to the domestic market in Ghana 3 TILCAP launches training manuals to disseminate information on Ghana’s VPA 17 Artisanal Milling defined 4 Woodcarvers push for a place in Ghana’s voluntary partnership A giant step towards formalizing Artisanal Milling 5 agreement amidst risks of being excluded 18 Artisanal millers -

The Origins and Brief History of the Ewe People

THE ORIGINS AND BRIEF HISTORY OF THE EWE PEOPLE Narrated By Dr. A. Kobla Dotse© Published in 2011 ©XXXX Publications Disclaimer The material we present here is provided to you mainly for educational and information purposes only. This information is not intended to be a substitute for a true history book on Ewes. Please consult any book on Ewes, your historian or any appropriate history book dealing with Ewes for deeper understanding of Ewes and their history. Publications, websites and the author shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss, damage, sickness or injury caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in this article and a subsequent book to be published. Ewe Country Boundaries The boundaries of the new African nations are those of the old British, Belgian, French, German, and Portuguese colonies. They are essentially artificial in the sense that some of them do not correspond with any well-marked ethnic divisions. Because of this the Ewes, like some other ethnic groups, have remained fragmented under the three different flags, just as they were divided among the three colonial powers after the Berlin Conference of 1844 that partitioned Africa. A portion of the Ewes went to Britain, another to Germany, and a small section in Benin (Dahomey) went to France. After World War I, the League of Nations gave the Germans- occupied areas to Britain and France as mandated territories. Those who were under the British are now the Ghanaian Ewes, those under the French are Togo, and Benin (Dahomey) Ewes, respectively.