Us Policy and Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazmin Rose (714) 930-5408 [email protected]

Jazmin Rose (714) 930-5408 [email protected] www.jazminrose.com EDUCATION: B.A. Broadcast Journalism, Biola University, December 2016 (La Mirada, CA) EXPERIENCE: TODAY Show (New York, NY) 03/19-Present Crash Researcher Responsible for gathering up-to-date/archived video elements, coordinating between crew and producer, logging video, coordinating with assignment desk, and additional editorial research for producers before overnight edit. NBC News (New York, NY) 09/18-05/19 News Associate NBC Nightly News with Lester Holt (09/18 — 12/18) Weekday responsibilities include: Logging, researching, finding characters/locations for stories, and assisting as “Rundown P.A.” by adding director cues, printing scripts, and spell-checking banners on iNews. -- Cut 2 extended interviews (multi-cam) on Avid for Nightly Digital -- Booked character for Tammy Leitner Flooded Cars Segment (aired 12/16/18) -- Booked character for Rehema Ellis “Green Book” Feature (aired 11/29/18) Fill-in weekend responsibilities include: Help with cutting VO’s/Teases for the show, gathering video, researching, pitching stories, and logging. NBC Digital Original Video (12/18-3/19) Assisting digital producers with gathering video (MAM/PAM), setting up equipment, editing on Adobe Premiere Pro, and shooting broll with Sony FS5, and pitching stories. Today Show (3/19-5/19) Performed as a crash researching gathering video elements and additional editorial research for producers before edit. KFMB-TV (San Diego, CA) 05/17-08/18 Producer (03/18-08/18) Responsible for 4:30A and 5:00A shows for CBS News 8. Capable of producing rundown, writing various anchor news segments and teases, and managing show times. -

Agent Orange: a Controversy Without End

Environmental Pollution and Protection, Vol. 3, No. 4, December 2018 100 https://dx.doi.org/10.22606/epp.2018.34002 Agent Orange: A Controversy without End Alvin L. Young* A. L. Young Consulting, Inc., Cheyenne, Wyoming, United States *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Confusion and misinformation are common when discussing Agent Orange, a tactical herbicide used in the Vietnam War. This is partially the result of inaccurate news coverage or false information that is purposely spread to deceive veterans. Sensationalized reporting has frequently left the public with a distorted view of what occurred in Vietnam and of the minimal risks related to the use of herbicides in an operational combat environment. However, such a discrepancy between perceived risks and actual risks has also been enhanced by a public policy where historical records and science have been ignored while favoring a policy of “presumptive” compensation promoted by the Agent Orange Act of 1991. The Act has resulted in a narrow focus on tactical herbicides as the key factor in explaining the health risks of Vietnam veterans, ignoring other important risk factors that occurred in the war in Vietnam, namely, widespread endemic tropical diseases and parasites, psychological and physiological impacts of war, and health and lifestyle. Thus, it is not surprising that the controversies surrounding the use of Agent Orange in Vietnam have raged for 40 years. Indeed, more than a million United States veterans and billions of dollars have been spent by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs in providing compensation and health care for unrelated diseases where the vast majorities are not deployment-related health problems or related to herbicide exposure, but rather to aging and quality of life issues. -

2015-2016 Chicago/Midwest Regional Emmy® Nominees

2015-2016 Chicago/Midwest Regional Emmy ® Nominees Chicago/Midwest Chapter National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences NATAS CHICAGO/MIDWEST CHAPTER 33 E. Congress, Suite 535 Chicago, IL 60605 312-369-8600 [email protected] chicagoemmyonline.org facebook.com/emmyschicago Twitter: chi_natas Category #1-a Outstanding Achievement for News Programming – Evening Newscast: Larger Markets (1-50) (Award to the Team of Reporters, Meteorologists, Anchors, Producers, Photographers, Editors, Directors, and Assignment Editors) • FOX6 News at 9:00 - November 10, 2015: Vince Condella. Stephanie Grady, Brad Hicks, Kelly Stoop, Jennifer Tamsen. WITI • 10pm Newscast: Gage Park Massacre Arrests: Maria Atkinson, Sylvia Barragan, Mario Bernal, Iris Berrios, Marali Madrid Burciaga, Alfonso Gutierrez, John Hodai, Jorge Lara, Anabel Monge, Rick Munoz, Javier Pacheco, Cesar Rodriguez, Wendy Straw, Curtis Sweat, Sebastian Torres, Alberto Urbina, Ricardo Vento. WSNS • CBS 2 10pm News McDonald Video Released: Marissa Bailey, Ryan Baker, Steve Baskerville, Audrina Bigos, Brad Edwards, Rob Johnson, Jeff Kiernan, Dana Kozlov, Jay Levine, Ginger Maddox, Megan Mawicke, David Parrish, Karen Rariden, Irika Sargent, Carol Thompson, Michele Youngerman, Deb Zimmer. WBBM • 10pm Newscast -- 11/24/15: Kathy Brock, Josh Bryant, Cheryl Burton, Rodney Correll, Rob Elgas, Ann Marie Esp, John Garcia, Chuck Goudie, Patricia Helmstetter, Glen Holcomb, Jennifer Hoppenstedt, Eric Horng, Dartise Johnson, Casey Klaus, Alyson Koch, Lauro Lopez, Ron Magers, James Mastri, Lisa McGonigle, Carleen Mosbach, Vince Munyon, Laura Podesta, Derrick Robinson, Jose Sanchez, Mark Scodro, Eric Siegel, Mark Urban, Douglas Whitmire, Christina Zambrano. WLS • NBC 5 News at 10: The Laquan McDonald Shooting: Dick Johnson, Katie Kim, Joe Kolina, Patrick Lake, Jennifer Lay-Riske, Tammy Leitner, Carol Marin, Natalie Martinez, Don Moseley, Phil Rogers, Allison Rosati, Rob Stafford. -

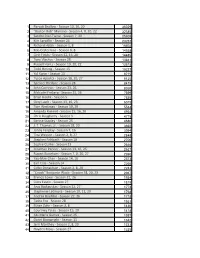

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx. -

NOMINEES for the 40Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY

NOMINEES FOR THE 40th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED NBC’s Andrea Mitchell to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award September 24th Award Presentation at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 25, 2019 (revised 8.19.19) – Nominations for the 40th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019, at a ceremony at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “The clear, transparent, and factual reporting provided by these journalists and documentarians is paramount to keeping our nation and its citizens informed,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO, NATAS. “Even while under attack, truth and the hard-fought pursuit of it must remain cherished, honored, and defended. These talented nominees represent true excellence in this mission and in our industry." In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to honor Andrea Mitchell, NBC News’ chief foreign affairs correspondent and host of MSNBC's “Andrea Mitchell Reports," with the Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award for her groundbreaking 50-year career covering domestic and international affairs. The 40th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards honors programming distributed during the calendar -

Journalism and Mass Communication Schools

Alabama • Alabama, University of mail: Box 870172, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0172. street: Reese Phifer Hall, 901 University Blvd., Tuscaloosa, AL 35487; Tel: (205) 348-4787, FAX: (205) 348-3836; Email: [email protected], College of Communication and Information Sciences, 1927. ACES, SPJ, NABJ, NPPA. Loy Singleton, Dean. FACULTY: Profs.: Elizabeth Aversa, Beth S. Bennett (chair, Communication Studies), Bruce Berger (Phifer professor), Andrew Billings (Reagan chair), Kimberly Bissell (assoc. dean Research, Southern Progress prof.), Rick Bragg, Matthew Bunker (Phifer prof.), Jeremy Butler, Karen J. Cartee, William Evans, William Gonzenbach, Karla Gower (Behringer prof.), Heidi Julien (dir., School of Library and Information Studies), Steven Miller, Yorgo Pasadeos, Joseph Phelps (chair, Advertising and Public Relations), Pamela Doyle Tran, Danny Wallace (EBSCO chair), Shuhua Zhou (assoc. dean, Graduate Studies); Assoc. Profs.: Jason Edward Black (asst. dean, Undergraduate Student Services), Gordon Coleman, Caryl Cooper (asst. dean, Undergraduate Studies), George Daniels, Anne Edwards, Janis Edwards, Anna Embree, Jennifer Greer (chair, Journalism), William Glenn Griffin, Lance Kinney, Margot Lamme, Wilson Lowrey, Steven MacCall, Carol Bishop Mills, Jeff Weddle, Glenda Williams (chair, Telecommunication and Film); Asst. Profs.: Dan Albertson, Meredith Bagley, Jane Baker, Laurie Bonnici, Robin Boylorn, Jennifer Campbell-Meier, Alexa Chilcutt, Kristen Heflin, Suzanne Horsley, Hyoungkoo Khang, Eyun-Jung Ki, Doohwang Lee, Regina Lewis, Mary Meares, Jamie Naidoo (Foster-EBSCO prof.), Matthew Payne, Rachel Raimist, Robert Riter, Chris Roberts, Adam Schwartz, Lu Tang, Kristen Warner; Lecturers: Chip Brantley, Dwight Cammeron, Andrew Grace, David Grewe; Instrs.: Angela Billings, Dianne Bragg, Michael Bruce, Chandra Clark, Nicholas Corrao, Treva Dean, Meredith Cummings, Susan Daria, Naomi Gold, Teri Henley, Robert Imbody, Michael Little, Daniel Meissner, Jim Oakley (placement dir.), Tracy Sims, Charles Womelsdorf. -

SIPA News January 2012

JANUARY 2012 SIPANEWS NATIONAL IDENTITY AND THE POWER OF PERCEPTION SIPANEWS VOLUME XXV No. 1 JANUARY 2012 Published semiannually by Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs The quickening pace of globalization over the past two decades has undermined traditional national From the Dean identities and helped to promote ethnic, social, cultural, and even transnational solidarities that com- pete for primacy. More than 200 million people worldwide now reside outside their country of birth. Most of the rest of the world’s population now live in cities that are becoming more and more diverse. As the essays in this issue of SIPA News demonstrate vividly, individual identities and attachments are changing on a vast scale. In some places, of course, economic crises and political tensions have fueled a revival of nationalist sentiment against outsiders, but in most of the world, urbanization, education, and rising consumption are making people more cosmopolitan. In many places, identity formation has become an object of policymaking for national as well as local governments and of lobbying (or marketing) by social entrepreneurs of all kinds. Governments seek to reshape the attitudes of potential foreign investors and end up creating or perpetuating national or local mythologies, while cultural symbols and achievements, from ancient ruins and transnational religiosity to pop music and football (soccer), are being deployed by governments and non-state actors alike to create a sense of community (or of tension and confrontation) where it did not exist before. These are powerful trends, pushed along by the rapid proliferation of new means of social communication. -

Introduces New Learning Style

^jethbridge Community College UbraO" Lethbridge Community College //V> Vol: XXXVI Issue: 15 Wednesday, March 6, 2002 / 1NSIDL£THIS Rem instructional building^'' \\EF.K introduces new learning style By Chris Hibbard EndBavonr Staff Five Lethbridge Community College staff have returned from Phoenix, Arizona with new knowledge and concepts pertaining to the operation of the new instructional building. Last spring, Jean Valgardson, VP of Curriculum and Instruction went to Phoenix for an initial visit to look at two very similar high tech computers that wiU be used in efficiency of computii^S^S^^d'^"^ SHUTE schools, Glendale and Mesa b/mmunity An OVervieW of the college with the new instructional building under Colleges. construction (centre). The building will be ready for classes beginning next fall. From that visit came conjunction with classroom instruction. education. the base model for LCC's new building "It refines the outcome attached to "It felt good, and the students seemed to be fully operational by September. leaming methods," said Valgardson. to like it," said Walker. "Since our visit last spring, there were "Learners will have to Usten better in The trip was joint-funded by some details to be ironed out. We class, because when they leave a lecture professional development funds and figured we'd be better off to leam from they have the skills to practice. If they Valgardson's administrative budget. example than from trial and error," said haven't been paying attention they'll be The new LCC building houses a Valgardson. in trouble. But there are lab guides and commons lab with 160 computers, Along with Valgardson there was the instructional aides to help them in that breakout rooms for small group work, team leader for applied management, case." and four theatres which can be Gloria Dannoch, and three business and There are few schools in Canada that individually used or combined for a office administration instructors, Rob offer the same high-tech atmosphere very large one. -

NOMINEES for the 40Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY

NOMINEES FOR THE 40th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED NBC’s Andrea Mitchell to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award September 24th Award Presentation at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 25, 2019 (revised 9.09.19) – Nominations for the 40th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019, at a ceremony at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “The clear, transparent, and factual reporting provided by these journalists and documentarians is paramount to keeping our nation and its citizens informed,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO, NATAS. “Even while under attack, truth and the hard-fought pursuit of it must remain cherished, honored, and defended. These talented nominees represent true excellence in this mission and in our industry." In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to honor Andrea Mitchell, NBC News’ chief foreign affairs correspondent and host of MSNBC's “Andrea Mitchell Reports," with the Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award for her groundbreaking 50-year career covering domestic and international affairs. The 40th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards honors programming distributed during the calendar -

Parvati Shallow

1 Parvati Shallow - Season 13, 16, 20 36029 2 "Boston Rob" Mariano - Season 4, 8, 20, 22 32385 3 Sandra Diaz-Twine - Season 7, 20 25909 4 Kim Spradlin - Season 24 23257 5 Richard Hatch - Season 1, 8 15602 6 Rob Cesternino - Season 6, 8 14558 7 Cirie Fields - Season 12, 16, 20 14485 8 Tony Vlachos - Season 28 13841 9 Russell Hantz - Season 19, 20, 22 13618 10 Todd Herzog - Season 15 10221 11 Yul Kwon - Season 13 9715 12 Tyson Apostol - Season 18, 20, 27 9125 13 Spencer Bledsoe - Season 28 8419 14 John Cochran - Season 23, 26 8020 15 Malcolm Freberg - Season 25, 26 7599 16 Brian Heidik - Season 5 7535 17 Ozzy Lusth - Season 13, 16, 23 6015 18 Tom Westman - Season 10, 20 5534 19 Amanda Kimmel - Season 15, 16, 20 4964 20 Chris Daugherty - Season 9 4715 21 Denise Stapley - Season 25 4680 22 J. T. Thomas, Jr. - Season 18, 20 3692 23 Jonny Fairplay - Season 7, 16 3094 24 Tina Wesson - Season 2, 8, 27 2848 25 Stephen Fishbach - Season 18 2700 26 Sophie Clarke - Season 23 2646 27 Jonathan Penner - Season 13, 16, 25 2627 28 Rupert Boneham - Season 7, 8, 20, 27 2390 29 Yau-Man Chan - Season 14, 16 2373 30 Earl Cole - Season 14 2266 31 Colby Donaldson - Season 2, 8, 20 2243 32 "Coach" Benjamin Wade - Season 18, 20, 23 2067 33 Brenda Lowe - Season 21, 26 1934 34 Ciera Eastin - Season 27 1819 35 Aras Baskauskas - Season 12, 27 1774 36 Stephenie LaGrossa - Season 10, 11, 20 1768 37 Andrea Boehlke - Season 22, 26 1718 38 Tasha Fox - Season 28 1523 39 Ethan Zohn - Season 3, 8 1440 40 Courtney Yates - Season 15, 20 1418 41 Abi-Maria Gomes - Season 25 1397 -

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints a History- 1959-2017

INSTANCES OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE ALLEGEDLY PERPETRATED BY MEMBERS OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS A HISTORY- 1959-2017 SIC LOQUITUR PRO SE Compiled by Deborah J. Diener RN BSN CLNC WE CANNOT CHANGE WHAT WE FAIL TO CONFRONT Child abuse dramatically increases the risk of 7 out of 10 of the leading causes of death; decreases life expectancy by 20 years; and this damage is passed genetically generation after generation. The lifelong health effects of child sexual abuse include: Brain atrophy; Suicide risk- GIRLS 2-4 times the risk and BOYS 4-12 times the risk; Psychological problems; Anorexia Bulimia; PTSD; High risk behaviors such as drug and alcohol abuse; Promiscuity and exploitation;Teenage pregnancies are higher than the norm in child sexual abuse victims; COPD 2-5 times the risk; Hepatitis 2-5; times the risk; Depression 4-5 times the risk; Lung cancer 33% higher risk; Ischemic heart disease 3.5 times the risk; ADHD 2.5 times the risk; & Self Harm. There is a substantial increase in delinquent acts leading to more incarcerations by a victim vs the general population. There is a high association with child abuse resulting in homelessness.1 Child predators on average, will abuse 175 children in their lifetime; some have admitted to over 1000 children.2 Researchers at Harvard have determined that “there is no cure for pedophilia” therefore the focus should be on protecting our children.3 A child predator will abuse 50-75 children before he is caught, but only 3% of predators are apprehended.