The June 2007 Floods in Hull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hull's Flying High..!

9 Queen’s Gardens 11 City Walls & Citadel Hull Road, HU1 2AB Hull’s fortifications were established in the early 14th century, consisting of the city walls, four main gates and Hull’s flying high.. up to thirty towers. ! Demolished during The future’s bright! the 1860s, the lasting 13 Paragon Interchange segment of Hull’s Amy Johnson,Wow!! the first Civil engineers shape our world and we built this city... Ferensway, HU1 3UT female pilot to fly alone citadel - now to be seen from Britain to Australia, was improve lives. If you want to make born in Hull on Wow!! at Victoria Dock - is all 1st July 1903. a real difference, why not become a that remains of a vast triangular fort dating civil engineer? Photo courtesy of Hull Daily Mail back to 1681. This area - once known as Queen’s Dock - was the site of Which of these are examples Princes Quay Shopping Centre, Hull’s first enclosed dock - excavated between 1774 and 12 Q: of Civil Engineering? 1778. The dock was the first of its kind outside London and HU1 2PQ covers a total area of 11 acres. The original name of the Dams, reservoirs, drains and sewers; transport by road, rail, dock was ‘The Old Dock’ but it was re-named ‘Queen’s’ water and air; bridges for vehicles, trains and pedestrians; when Queen Victoria visited Hull in 1854. seaports, docks, airports, canals and aqueducts; power stations, renewable energy, pipelines and the structures that support towers and buildings. The Paragon Interchange, refurbished Queen Victoria Square 10 in 2000, links the bus station to the Hull, HU1 3RQ 150-year-old Victorian train station and Queen Victoria Square was now serves over 2.25 million people. -

Passionate for Hull

Drypool Parish, Hull October 2015 WANTED Drypool Team Rector / Vicar of St Columba’s Passionate for Hull Parish Profile for the Team Parish of Drypool, Hull 1/30 Drypool Parish, Hull October 2015 Thank you for taking the time to view our Parish profile. We hope that it will help you to learn about our community of faith and our home community; about our vision for the future, and how you might take a leading role in developing and taking forward that vision. If you would like to know more, or visit the Parish on an informal basis, then please contact any one of the following Revd Martyn Westby, Drypool Team Vicar, with special responsibility for St John’s T. 01482 781090, E. [email protected] Canon Richard Liversedge, Vice-chair of PCC & Parish Representative T. 01482 588357, E. [email protected] Mrs Liz Harrison Churchwarden, St Columba’s T. 01482 797110 E. [email protected] Mr John Saunderson Churchwarden, St Columba’s & Parish Representative T. 01482 784774 E. [email protected] 2/30 Drypool Parish, Hull October 2015 General statement of the qualities and attributes that the PCC would wish to see in a new Incumbent We are praying and looking for a priest to join us as Rector of Drypool Team Parish and vicar of St Columba’s Church. We seek someone to lead us on in our mission to grow the Kingdom of God in our community, and these are the qualities we are looking for. As Team Rector The ability to: Embrace a call to urban ministry and a desire to develop a pastoral heart for the people of the various communities in the Parish Be Strategic and Visionary Work in partnership with existing Team Vicar and Lay Leadership Developing and empowering Lay Leadership further Respect the uniqueness of each congregation and continue unlocking the sharing of each others strengths Be organised and promote good organisation and communication Someone who can grow to love this community as we love it. -

Humber Area Local Aggregate Assessment

OCTOBER 2019 (Data up to 2018) HUMBER AREA LOCAL AGGREGATE ASSESSMENT CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 3 Development Plans 4 Spatial Context 5 Environmental Constraints & Opportunities 6 2. GEOLOGY & AGGREGATE RESOURCES 8 Bedrock Geology 8 Superficial Geology 9 Aggregate Resources 10 Sand and Gravel 10 Chalk & Limestone 11 Ironstone 11 3. ASSESSMENT OF SUPPLY AND DEMAND 12 Sand & Gravel 12 Crushed Rock 14 4. AGGREGATE CONSUMPTION & MOVEMENTS 16 Consumption 16 Imports & Exports 18 Recycled & Secondary Aggregates 19 Marine Aggregates 23 Minerals Infrastructure 25 6. FUTURE AGGREGATE SUPPLY AND DEMAND 28 Managed Aggregate Supply System (MASS) 28 Approaches to Identifying Future Requirement 29 Potential Future Requirements 34 7 CONCLUSION 36 Monitoring and Reviewing the Local Aggregates Assessment 37 Consideration by the Yorkshire and Humber Aggregates Working Party 37 APPENDIX 1: YHAWP CONSULTATION RESPONSES TO A DRAFT VERSION OF THIS LAA, THE COUNCILS’ RESPONSE, AND ANY AMENDMENTS TO THE DOCUMENT AS A RESULT. 41 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The requirement to produce an annual Local Aggregate Assessment (LAA) was introduced through the publication of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in March 2012 and is still a requirement set out in the revised NPPF (2019). The Government issued further guidance on planning for minerals in the National Planning Practice Guidance (NPPG), incorporating previous guidance on the Managed Aggregate Supply System (MASS). This report is the sixth LAA that aims to meet the requirements set out in both of these documents. It is based on sales information data covering the calendar years up to 2018. Landbank data is 2018-based. Sales and land bank information is sourced from annual surveys of aggregate producers in the Humber area (East Riding of Yorkshire, Kingston upon Hull, North East Lincolnshire & North Lincolnshire), alongside data from the Yorkshire & Humber Aggregates Working Party Annual Monitoring Reports, planning applications, the Crown Estate, and the Environment Agency. -

River Hull Integrated Catchment Strategy Strategy Document

River Hull Advisory Board River Hull Integrated Catchment Strategy April 2015 Strategy Document Draft report This Page is intentionally left blank 2 Inner Leaf TITLE PAGE 3 This page is intentionally left blank 4 Contents 1 This Document.............................................................................................................................17 2 Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................18 3 Introduction and background to the strategy ..................................20 3.1 Project Summary .................................................................................................................................... 20 3.2 Strategy Vision ........................................................................................................................................ 20 3.2.1 Links to other policies and strategies .......................................................................................21 3.3 Background .............................................................................................................................................. 22 3.3.1 Location ........................................................................................................................................... 22 3.3.2 Key characteristics and issues of the River Hull catchment ...............................................22 3.3.3 EA Draft River Hull Flood Risk Management Strategy .........................................................26 -

Highways Agency Project Support Framework A63 Castle Street Improvements, Hull

Highways Agency Project Support Framework A63 Castle Street Improvements, Hull Scheme Assessment Report (Options Selection Stage) Document Reference: W11189/T11/05 Final Rev 6 FEBRUARY 2010 HIGHWAYS AGENCY PROJECT SUPPORT FRAMEWORK CASTLE STREET IMPROVEMENTS - HULL SCHEME ASSESSMENT REPORT (OPTIONS SELECTION STAGE) FEBRUARY 2010 PROJECT SUPPORT FRAMEWORK A63 CASTLE STREET IMPROVEMENTS – HULL SCHEME ASSESSMENT REPORT (W11189/T11/05) A63 CASTLE STREET IMPROVEMENTS - HULL SCHEME ASSESSMENT REPORT (OPTIONS SELECTION STAGE) FEBRUARY 2010 Revision Record Revision Ref Date Originator Checked Approved Status 1 14/12/09 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Draft 2 08/01/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Draft 3 13/01/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Draft 4 25/01/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Final 5 17/02/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Final 6 26/02/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Final This report is to be regarded as confidential to our Client and it is intended for their use only and may not be assigned. Consequently and in accordance with current practice, any liability to any third party in respect of the whole or any part of its contents is hereby expressly excluded. Before the report or any part of it is reproduced or referred to in any document, circular or statement and before its contents or the contents of any part of it are disclosed orally to any third party, our written approval as to the form and context of such a publication or disclosure must be obtained. Prepared for: Prepared by: Highways Agency Pell Frischmann Consultants Ltd Major Projects National George House Lateral George Street 8 City Walk Wakefield Leeds WF1 1LY LS11 9AT Tel: 01924 368 145 Fax: 01924 376 643 PROJECT SUPPORT FRAMEWORK A63 CASTLE STREET IMPROVEMENTS - HULL SCHEME ASSESSMENT REPORT (W11189/T11/05) CONTENTS 1. -

Future of Stormwater Lagoon Hull

Future of Stormwater Lagoon Hull LAGOON HULL A1165 N HULL 1km River front development A1033 opportunity areas BALANCED Victoria Dock Consent ready outer A63 harbour development 26-41% REDUCTION IN New four lane highway TRAFFIC ON THE A63 (9.6km) Outer harbour DEFENCE (2km!) 100% The ambitious Lagoon Hull project aims to protect Hessle IMPOUNDED LAGOON (5KM!) Tidal flood protection the city from flooding, while improving transport for at least 100 years connectivity and reinvigorating the local economy. Y £300M U A R Journey time savings Nadine Buddoo reports. E S T E R M B 1,600 100% THROUGH TRAFFIC H U MOVED TO LAGOON ROAD Construction jobs ull is one of the cities estuary – on the southern edge of in the UK which are Hull – compounds its vulnerability £1bn Gross value added most vulnerable cities KEY FACTS to flooding. per annum to coastal flooding “The city is almost trapped by Bridge Humber and rising sea levels. £1.5bn water,” says Hatley. “There has been But the proposed pluvial flooding, which we saw in Lagoon Hull project aims to change Cost of Lagoon 2007, where a massive downpour one or two types of flooding, but Hull is Hall that. into saturated land led to surface vulnerable to all of them. It is a perfect The £1.5bn scheme will involve the water runoff just pooling everywhere storm of all the risk factors.” construction of an 11km causeway in throughout the city before it even got Lagoon Hull aims to deliver a holistic the Humber estuary, creating a non- 11km to the drains. -

East Riding Proposed Submission Local Plan: Duty to Cooperate Background Paper

East Riding Proposed Submission Local Plan: Duty to Cooperate Background Paper East Riding Proposed Submission Local Plan Duty to Cooperate: Background Paper January 2014 1 East Riding Proposed Submission Local Plan: Duty to Cooperate Background Paper 1. Introduction 1.1 This Background Papers provides the context against which the East Riding Local Plan (Strategy Document and Allocations Document) has been prepared, specifically in relation to satisfying the requirements of the Duty to Cooperate 1. The duty requires local planning authorities to: • engage constructively, actively and on an ongoing basis; and • have regard to the activities of other bodies. 1.2 The bodies prescribed for the purposes of the Duty to Cooperate 2 are: • local planning authorities, or a county council that is not a local planning authority; • the Environment Agency; • the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England (known as English Heritage); • Natural England; • the Mayor of London; • the Civil Aviation Authority; • the Homes and Communities Agency; • each Primary Care Trust established under section 18 of the National Health Service Act 2006 or continued in existence by virtue of that section; • the Office of Rail Regulation; • Transport for London; • each Integrated Transport Authority; • each highway authority within the meaning of section 1 of the Highways Act 1980 (including the Secretary of State, where the Secretary of State is the highways authority); • the Marine Management Organisation; and • each Local Enterprise Partnership. 1.3 In addition, paragraph 180 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) highlights that local planning authorities should also work collaboratively with Local Nature Partnerships. 1.4 The Background Paper sets out East Riding of Yorkshire Council's evidence of having cooperated with these bodies 3 on strategic matters. -

Sutton Village Conservation Area Appraisal

Sutton Village Conservation Area Appraisal 1 Summary 1.1 The purpose of this appraisal is to define and record what makes Sutton Village an area of special architectural and historic interest. This is important for providing a sound basis, defensible on appeal, for Local Plan policies and development control decisions, as well as for the formulation of proposals for the preservation or enhancement of Sutton. The clear definition of this special interest, and therefore of what it is important to retain, also helps to reduce uncertainty for those considering investment or development in the area. 1.2 The writing of this appraisal has involved consulting many different sources, which are listed in the Bibliography at the end. Many of them have been quoted or directly referred to in the text, and these are acknowledged by means of superscripts and listed under “References” at the end. 1.3 This appraisal is not intended to be comprehensive and omission of any particular building, feature or space should not be taken to imply that it is of no interest. 2 Introduction 2.1 Sutton retains the character of a traditional village with winding streets of mediaeval origin overlooked by a 14th century church and some property boundaries recalling the mediaeval open field system. In the 19th century proximity to Hull led to the development of institutional buildings and big houses for wealthy Hull residents. During the course of the mid to late 20th century the village was surrounded, but not obliterated, by modern housing estates. Despite this it retains extensive areas of green space with many trees and bushes throughout. -

Drypool Parish Profile 2018 20S-40S

Drypool Parish Profile 2018 20s-40s Minister The Parish Drypool Parish is in the heart of East Hull. It is a wonderfully diverse and interesting parish, bordered by the River Humber and River Hull on two sides, with the city’s largest park on another. About 24,000 people live here, and in the 2011 census 9,200 of them were aged 18-44. According to the Church Urban Fund, Drypool is one of the 6% most deprived parishes in England, but that does not tell the full story. The parish includes the century-old Garden Village, built by a Quaker industrialist, and the modern Victoria Dock development, which attracts young professionals. It ranges from streets dominated by social housing, to industrial areas that have seen significant investment from the likes of Reckitts and Siemens. Being City of Culture in 2017 has given the city of Hull a boost in confidence, and as churches we are working to make the most of the increased openness this brings. Drypool is a great place to live – we are next to the City Centre, with all its shops, restaurants, museums, theatres etc; the Humber and East Park provide beautiful open spaces; the bustling shopping street of Holderness Road goes through the heart of the parish; we are a short drive from the beach at Hornsea or the countryside of the Yorkshire Wolds; we are just 5 minutes from the ferry to Europe too. There are 7 primary schools in the parish, and our churches have links with all of them. Drypool is an evangelical parish with 3 churches representing different styles, and reaching very different areas. -

Appendix 3.2: Route Corridor Investigation Study

T N E M U C O D 6.3.2 Appendix 3.2: Route Corridor Investigation Study River Humber Gas Pipeline Replacement Project Under Regulation 5(2)(a) of the Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 Application Reference: EN060004 April 2015 May 2013 Number 9 Feeder Replacement Project Final Route Corridor Investigation Study Number 9 Feeder Replacement Project Final Route Corridor Investigation Study Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 Appendix 5 Figures 2 Route Corridor and Options Appraisal Methodology 4 Figure 1 – Area of Search 61 Figure 2 – Route Corridor Options 62 3 Area of Search and Route Corridor Identification 5 Figure 2 (i) – Route Corridor 1 63 4 Route Corridor Descriptions 7 Figure 2 (ii) – Route Corridor 2 64 5 Route Corridor Evaluation 8 Figure 2 (iii) – Route Corridor 3 65 Figure 2 (iv) – Route Corridor 4 66 6 Statutory Consultee and Key Stakeholder Consultation 14 Figure 2 (v) – Route Corridor 5 67 7 Summary and Conclusion 15 Figure 3 – Primary Constraints 68 8 Next Steps 15 Figure 4 – Secondary Constraints 69 Figure 5 – Additional Secondary Constraints 70 9 Abbreviations and Acronyms 15 Figure 6 – Statutory Nature Conservation Sites 71 10 Glossary 16 Figure 7 – Local Nature Conservation Sites 72 Appendix 1 - Population and Planning Baseline 17 Figure 8 – Historic Environment Features 73 Figure 9 – National Character Areas 74 Appendix 2 - Engineering Information 19 Figure 10 – Landscape Designations 75 Appendix 3 - Environmental Features 23 Figure 11 – Landscape Character 76 Appendix -

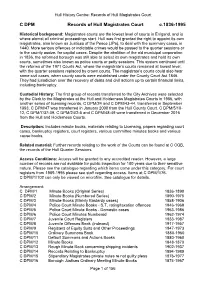

C DPM Records of Hull Magistrates Court C.1836-1995

Hull History Centre: Records of Hull Magistrates Court C DPM Records of Hull Magistrates Court c.1836-1995 Historical background: Magistrates courts are the lowest level of courts in Enlgand, and is where alomst all criminal proceedings start. Hull was first granted the right to appoint its own magistrates, also known as Justices of the Peace (JPs), to deal with the summary cases, in 1440. More serious offences or indictable crimes would be passed to the quarter sessions or to the county assize, for capital cases. Despite the abolition of the old municipal corporation in 1836, the reformed borough was still able to select its own magistrates and hold its own courts, sometimes also known as police courts or petty sessions. This system continued until the reforms of the 1971 Courts Act, where the magistrate’s courts remained at lowest level, with the quarter sessions replaced by crown courts. The magistrate’s courts could also hear some civil cases, when county courts were established under the County Court Act 1846. They had jurisdiction over the recovery of debts and civil actions up to certain financial limits, including bankruptcy. Custodial History: The first group of records transferred to the City Archives were selected by the Clerk to the Magistrates at the Hull and Holderness Magistrates Courts in 1986, with another series of licensing records, C DPM/24 and C DPM/43-44, transferred in September 1993. C DPM/47 was transferred in January 2008 from the Hull County Court. C DPM/5/10- 12, C DPM/7/37-39, C DPM/24/2-5 and C DPM/48-49 were transferred in December 2016 from the Hull and Holderness Courts. -

Australia Uk North America

OCTOBER 25 (GMT) – OCTOBER 26 (AEST), 2019 YOur dAILY TOP 12 STOrIES FrOM FRANK NEWS FuLL STOrIES STArT ON PAGE 3 NORTH AMERICA UK AUSTRALIA ‘Closed’ inquiry condemned PM will keep pushing for election Last Uluru climbers come down A leading Senate ally of President Donald Chancellor Sajid Javid says the The last climbers allowed to scale Uluru Trump has introduced a resolution government will push “again and again” have come down from the ancient and condemning the Democratic-run for a general election if the opposition sacred monolith, which is now officially House for pursuing an “illegitimate denies Boris Johnson a pre-Christmas closed for climbing. A group of eight held impeachment inquiry” and demanding poll. The Prime Minister said he would hands and stepped off the rock together that Republicans be given more chances give MPs more time to consider his Brexit about 7pm, local time, escorted by two to question witnesses. The nonbinding deal if they agreed to an election on rangers. Among them was Jayson Dudas resolution announced by GOP Sen. December 12. But Labour – whose votes from Las Vegas, who flew to Australia Lindsey Graham of South Carolina gives will be needed if he is to get the two- specifically to climb the rock. “I know Senate Republicans a chance to show thirds majority in the Commons which he there’s a big controversy. I respect the support for Trump. requires to go the country – has yet to first nations but since it’s an optional say what it will do. thing to do I decided to do it,” he said.