Full Advantage of the Beauty of Lakshadweep

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Affairs December 2013

Current Affairs December 2013 RATHNAKUMAR R. Email address: [email protected] © 2013 www.gktoday.in Price: Rs. 50/- Published by: GKToday (www.gktoday.in ) Disclaimer While all care has been taken in the preparation of this material, no responsibility is accepted by the author(s) for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies. The material provided in this resource has been prepared to provide general information only. It is not intended to be relied upon or be a substitute for legal or other professional advice. No responsibility can be accepted by the author for any known or unknown consequences that may result from reliance on any information provided in this publication Current Affairs Compendium December 2013 Contents ......................................... 6 ........................................................... 7 No capital gains tax or stamp duty on foreign banks converting to WoS - - .................. 7 Medium enterprises to be included under priority sector: RBI - .. 8 Cyber Coalition 2013: NATO’s largest ever cyber security exercise held in Estonia .......................................................................................................... 8 Direct cash transfer better option than other anti poverty schemes: Planning Commission ........................................................................................ 9 P.V. Sindhu clinches Macau Grand Prix .................................................. 9 Suwannapura bags India Open golf tournament .......................................................................................... -

IBPS CLERK CAPSULE for ALL COMPETITIVE EXAMS Exclusively Prepared for RACE Students Issue: 04 | Page : 102 | Topic : IBPS CAPSULE | Price: Not for Sale

IBPS CLERK CAPSULE for ALL COMPETITIVE EXAMS Exclusively prepared for RACE students Issue: 04 | Page : 102 | Topic : IBPS CAPSULE | Price: Not for Sale INDEX TOPIC Page No BANKING & FINANCIAL AWARENESS 2 LIST OF INDEXES BY VARIOUS ORGANISATIONS 11 GDP FORECAST OF INDIA BY VARIOUS ORGANISATION 15 LIST OF VARIOUS COMMITTEE & ITS HEAD 15 LOAN SANCTIONED BY NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL BANKS TO 17 INDIA PENALITY IMPOSED BY RBI TO VARIOUS BANKS IN INDIA 18 LIST OF ACQUISTION & MERGER 18 APPS/SCHEMES/FACILITY LAUNCHED BY VARIOUS 19 BANKS/ORGANISATIONS/COMPANY STATE NEWS 22 NATIONAL NEWS 38 IIT’S IN NEWS 46 NATIONAL SUMMITS 47 INTERNATIONAL SUMMITS 51 INTERNATIONAL NEWS 52 BUSINESS AND ECONOMY 60 LIST OF AGREEMENTS/MOU’S SIGNED 66 BRAND AMBASSADORS / APPOINTMENTS 68 AWARDS & HONOURS 70 BOOKS & AUTHORS 74 SPORTS NEWS 78 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 86 DEFENCE EXERCISES 93 IMPORTANT EVENTS OF THE DAY 94 OBITUARY 96 CABINET MINISTERS 2019 / LIST OF MINISTERS OF STATE 101 (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) CHIEF MINISTERS AND GOVERNORS 102 ________________________________________________________ 7601808080 / 9043303030 RACE Coaching Institute for Banking and Government Jobs www. RACEInstitute. in Courses Offered : BANK | SSC | RRB | TNPSC |KPSC 2 | IBPS CLERK CAPSULE | IBPS CLERK 2019 CAPSULE (JULY – NOVEMBER 2019) BANKING AND FINANCE Punjab & Sind Bank has set up a centralized hub named “Centralised MSME & Retail Group” (Cen MARG) for processing retail and Micro, Small and RBI gets the power to regulate housing finance companies instead Medium Enterprises (MSME) loans for better efficiency of branches in of NHB business acquisition. It is headquartered in New Delhi. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman stated that India's central bank, Wilful defaults exceed $21 billion in India for the year 2018-19, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) will now be given power to takes over as the SBI holds the highest regulator of Housing Finance Firms(HFFs) instead of NHB(National Housing The state-owned banks in India stated that Rs. -

India Extended US$18 Mn Line of Credit to Maldives for Expansion of Fishing Facilities at MIFCO

India extended US$18 mn Line of Credit to Maldives for expansion of fishing facilities at MIFCO NATIONAL NEWS Haryana Govt launched Mahila Evam Kishori Samman Yojana & Mukhya Mantri Doodh Uphar Yojana for state’s girls & women The state government of Haryana has launched two schemes, namely “Mahila Evam Kishori Samman Yojana” and “Mukhya Mantri Doodh Uphar Yojana” with a total budget of Rs 256 Crore was launched by the Chief Minister of Haryana Manohar Lal Khattar. Mahila Evam Kishori Samman Yojana is launched to provide free sanitary napkins to girls and women of Below Poverty Line (BPL) families. Mukhya Mantri Doodh Uphar Yojana is to provide fortified flavoured skimmed milk powder to women and children. The schemes mainly focusses on the enhancement of the “Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao” campaign. Fact: Governor of Haryana - Satyadeo Narain Arya India extended US$18 mn Line of Credit to Maldives for expansion of fishing facilities at MIFCO India has extended the Line of Credit (LoC) worth US$18 million to the Government of Maldives for the expansion of fishing facilities at Maldives Industrial Fisheries Company (MIFCO). MIFCO will expand the fishing facilities by the development of fish collection and storage facilities, and the setting up of a tuna cooked plant and fishmeal plant. The amount will also be utilized to develop a 50 tonne ice plant in Gemanafushi, Gaafu Dhaalu Atoll, in addition to a 100 tonne ice storage facility. Fact: Maldives capital – Male President of Maldives – Ibrahim Mohamed Solih ‘Moothon’, ‘Son Rise’ wins awards at 20th edition of New York Indian Film Festival Malayalam film ‘Moothon’ and National Award winning documentary ‘Son Rise’ won awards at the 20th edition of New York Indian Film Festival (NYIFF) of Indo-American Arts Council (IAAC). -

Actress Mouni Roy Who Plays the Role Kunal Kapoor and Represent It in 1948 Summer of Tapan Das’S(Akshay Kumar’S) Wife SYNOPSIS: Akshay Kumar Olympics

Community Community Qatar Cathy Academy Alderson P6Sidra P16 talks celebrates first about natural IB Diploma massage and Programme techniques for results. wellness. Thursday, August 16, 2018 Dhul-Hijja 5, 1439 AH Doha today 330 - 440 ARTEFACTS: Medical artefacts, including a jar once used to hold leeches, at the Science Center collection at Taylor Community Resource Center in St. Louis. COVER Q for quirky STORY What’s hiding in the Science Center’s vault? Shrunken heads, an iron lung and Mork. P4-5 REVIEWS SHOWBIZ Ready Player One is a I have more freedom in virtual disappointment. fi lms, says Sobhita. Page 14 Page 15 2 GULF TIMES Thursday, August 16, 2018 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.46am Shorooq (sunrise) 5.08am Zuhr (noon) 11.38am Asr (afternoon) 3.07pm Maghreb (sunset) 6.11pm Isha (night) 7.41pm USEFUL NUMBERS Ploey: You Never Fly Alone family migrates in the fall. He must survive the arctic winter, DIRECTION: Árni Ásgeirsson vicious enemies and himself in order to be reunited with his CAST: Jamie Oram, Harriet Perring, Iain Stuart Robertson beloved one next spring. Emergency 999 SYNOPSIS: A plover chick has not learned to fl y when his THEATRE: The Mall, Landmark, Royal Plaza Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Qatar Airways 44496000 Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, 44393333 Qatar General Electricity and Water Corporation 44845555, 44845464 Primary Health Care Corporation 44593333 44593363 Qatar Assistive Technology Centre 44594050 Qatar News Agency 44450205 44450333 Q-Post – General Postal Corporation 44464444 Humanitarian Services Offi ce (Single window facility for the repatriation of bodies) Ministry of Interior 40253371, 40253372, 40253369 Ministry of Health 40253370, 40253364 Hamad Medical Corporation 40253368, 40253365 Gold won 3 gold medals under British rule faced willingly to make India Proud. -

PLUTUS IAS 1.India Extends Line of Credit Worth 18 Million US Dollars to Maldives

CLICK ON -PLUTUS IAS 1.India extends Line of Credit worth 18 million US dollars to Maldives. ● India has extended Line of Credit worth 18 million US dollars to the Government of Maldives for the expansion of fishing facilities at Maldives Industrial Fisheries Company (MIFCO). ● The project envisages investment in fish collection and storage facilities and the setting up of a tuna cooked plant and fishmeal plant. ● It is part of the 800 million US dollars line of credit offered by India with repayment tenor of 20 yearsPLUTUS and a 5-year moratorium. IAS ● The loans will be issued through EXIM bank when the government of Maldives will present India with the proposals for future projects. 2.RBI to set up 'Innovation Hub'. Join Telegram Group https://t.me/studymaterialofexam IAS ● The Reserve Bank will set up an 'Innovation Hub' in the country for ideation and incubation of new capabilities which can be leveraged to deepen financial inclusion and promote efficient banking services. ● The Hub will act as a centre for ideation and incubation of new capabilities that can create innovative and viable financial products to help achieve the wider objectives of deepening financial inclusion, efficient banking services, business continuity in times of emergency, and strengthening consumer protection, among others. ● It is said that the central bank earlier took various initiatives for setting up a Regulatory Sandbox. ● Regulatory sandboxPLUTUS (RS) usually refers to live testing of new products or services in a controlled/test regulatory environment for which regulators may (or may not) permit certain relaxations for the limited purpose of testing. -

Reasoning Ability Number of Particiapants - 3237

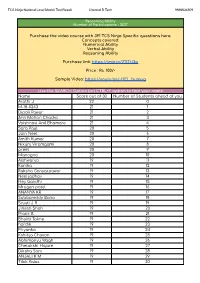

TCS Ninja National Level Mockk Test Result Channel B.Tech 9566634509 Reasoning Ability Number of Particiapants - 3237 Purchase the video course with 391 TCS Ninja Specific questions here: Concepts covered: Numerical Ability Verbal Ability Reasoning Ability Purchase link: https://imjo.in/ZS7U3w Price : Rs. 100/- Sample Video: https://youtu.be/-HEL_buoxyg Use the SEARCH Option (or) CTRL+F option to find your name Name Score out of 30 Number of Students ahead of you Arathi J 22 0 M-18-0243 21 1 Dipali Pawar 21 2 Ann Mohan Chacko 21 3 Vaishnavi Anil Bhamare 21 4 Sara Paul 20 5 Jain Neel 20 6 Amith Kumar 20 7 Nikunj Viramgami 20 8 preet 20 9 Manogna 20 10 Aishwarya 19 11 Kanika 19 12 Raksha Ganyarpawar 19 13 Neel jadhav 19 14 Hey Gandhi 19 15 Mrugen patel 19 16 ANANYA KR 19 17 Subbareddy Bana 19 18 Srusti J R 19 19 Jinesh Shah 19 20 Pratik B. 19 21 Bhakti Takne 19 22 hardik 19 23 Priyanka 19 24 Kshitija Chavan 19 25 Abhimanyu Wagh 19 26 Chetakshi Hajare 19 27 Diksha Soni 19 28 ANJALI K M 19 29 Tilak Kalas 19 30 TCS Ninja National Level Mockk Test Result Channel B.Tech 9566634509 G. Madhuri 19 31 Tushar Panchangam 19 32 Srijith Bhat 19 33 madhumitha 18 34 Jainam D. Belani 18 35 Manan Patel 18 36 Paheli Bhaumik 18 37 Harshil Shah 18 38 Disha Kotari 18 39 Morusu Yogesh 18 40 Amer Khan 18 41 SHAIK KHALID MATEEN 18 42 Abbas Ali Shaik 18 43 Shaik Mahammed Muzamil 18 44 Yogeshwari R 18 45 Akshit Chaudhary 18 46 Solanki Akash 18 47 Yuvraj Sharma 18 48 Varun Kumar 18 49 Nainitha N Shetty 18 50 Shweta 18 51 Shreyas Shetty 18 52 Preetam Ghosh 18 53 Nikhil -

Other States

www.gradeup.co 1 www.gradeup.co Important News: Other States August 2020 ✓ Madhya Pradesh state government has identification number. The 8-digit number will launched a public awareness campaign “Ek enable seamless delivery of state government Mask-AnekZindagi” from August 1-15. services. ✓ Maharashtra government approved MagNet ✓ Uttarakhand state is set develop India’s first project worth Around Rs 1,000 crore to Help Snow Leopard Conservation centre. Farmers. Note: The main aim of the centre is to Note: This will boost the fruit and vegetable conserve and restore Himalayan ecosystems. It production and will improve processing and also aims to conserve elusive snow leopards minimise the losses in the sector of and other endangered Himalayan species. A perishables. number of snow leopards has been spotted in ✓ Andhra Pradesh state government has signed the districts of Pithoragarh and Uttarkashi. an MoU with Hindustan Unilever Ltd, P&G ✓ Haryana state government has launched and ITC to Support Economic Empowerment “Mahila Evam Kishori Samman Yojana” to of Women. provide free sanitary napkins to girls and ✓ Union territories Dadra and Nagar Haveli & women of below poverty line (BPL) families. Daman and Diuhas launched E-Gyan Mitra ✓ Haryana state government has launched mobile application for online education. “:Mukhya Mantri DoodhUphar Yojana” to Note: Through the app, the students from provide fortified flavoured skimmed milk primary till the higher secondary can take powder to women and children. online classes along with attempting. The app ✓ Chhattisgarhgovernment has launched will have lectures and quizzes posted by “Shaheed Mahendra Karma teachers along with a system of monitoring in TendupattaSangrahakSamajik Suraksha which teachers can monitor students’ progress Yojana” for tendu leaves collectors. -

Research Update (July-Dec 2020)

Azim Premji University Research Update (July-Dec 2020) 1 Note from the Research Centre 2020 has been one of the most difficult of years. It was listed by the UN as the “International Year of Plant Health” and by the World Health Organization as the “Year of the Nurse and Midwife”. Sadly, the main thing the year will be remembered for is the COVID-19 Pandemic. As the year draws to an end, it is time for us to look forth with hope and expectation to a very different 2021. For the past two years, Azim Premji University has brought out a newsletter at regular intervals, to keep us updated on the research we collectively conduct. What started as a simple exercise of collation became more than a summary, as we experimented with different sections, and added new formats. As 2020 draws to a close, we have changed the format to a ‘magazine-like’ version. In this issue, you will find the regular newsletter coverage of articles, journal papers, research, etc. In addition, you will also find a new thematic focus: with some crystal ball-gazing into the future, we collectively engage in “Heralding 2021”. We have tried to make it as readable and visually rich as possible. As said earlier, we are evolving with time, and if you have any comments to share on the content, format or look n feel, do drop us a mail on [email protected] In the end, as we ring in the new year – 2021, declared as the “International Year of Peace and Trust,” and “the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development” by the UN, one can only hope and pray that it does not get stamped by one label or defined by one trend. -

Curriculum-Vitae

Roshan Mathew B.Tech(Civil), A.M.I.E. Civil Engineer Curriculum-Vitae CAREER OBJECTIVE Secure a challenging position in an established organization, where my initiative, ambition and skills are utilized to its full potential and where there are sample opportunities for improvement of my skills and potential for advancement. Intended to secure a challenging position where I can utilize all my skills and abilities effectively as an Engineer and that offers professional growth while being resourceful, innovative and flexible. JOB DESCRIPTION Organization : WVA Consulting Engineers, Kerala, India Project : Grover Apartment, Thiruvankulam, India Designation : Structural Engineer-Industrial training Duration : June 2017 to July 2017 Responsibilities : • Analyzed photographs, drawings and maps to inform the direction of projects as well as the overall budget constraints • Created cost effective, sustainable and safe plans for large and small building designing • Completed accurate engineering calculations for different loads which would be acting upon the structure • Followed standards and procedures to maintain safe structural designs • Performed drafting duties for professionals and coordinated architects and engineers • Prepared reports, designs and drawings • Collaborated with team to ensure smooth workflow and efficient organization operations • Assessed the environmental impact and risks connected to projects Organization : K.J. Raphel Government Contractor, Kerala, India Project : Police station, Mananthavady, India Designation : Project -

Numerical Ability Number of Particiapants - 3627

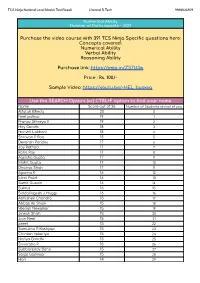

TCS Ninja National Level Mockk Test Result Channel B.Tech 9566634509 Numerical Ability Number of Particiapants - 3627 Purchase the video course with 391 TCS Ninja Specific questions here: Concepts covered: Numerical Ability Verbal Ability Reasoning Ability Purchase link: https://imjo.in/ZS7U3w Price : Rs. 100/- Sample Video: https://youtu.be/-HEL_buoxyg Use the SEARCH Option (or) CTRL+F option to find your name Name Score out of 26 Number of Students ahead of you Alfatah Bheda 20 0 Neel jadhav 19 1 Pranav Athreya V 19 2 Hey Gandhi 18 3 Harshil Lakhani 18 4 Shravan P Rao 18 5 Devansh Pandey 17 6 Jay Rathod 17 7 Rohit Roy 17 8 Aayisha Gupta 17 9 Mohit Gupta 17 10 Dhairya Shah 17 11 Aparna K 16 12 Meet Patel 16 13 Sumit Gusain 16 14 Sukrut 16 15 Siddalingesh J Huggi 16 16 Abhishek Chandra 15 17 Abbas Ali Shaik 15 18 Veenali Newalkar 15 19 Jinesh Shah 15 20 Jain Neel 15 21 preet 15 22 Sumukha R Kashyap 15 23 Chintan Vekariya 15 24 Nofiya Gandhi 15 25 Srivarsha P 15 26 Subbareddy Bana 15 27 Saijal Gadewar 15 28 Hari 14 29 TCS Ninja National Level Mockk Test Result Channel B.Tech 9566634509 madhumitha 14 30 trilok 14 31 Deep Paghdar 14 32 Jayachndra C D 14 33 Prasun Chakraborty 14 34 DIBYARANJAN DAS 14 35 Srusti J R 14 36 Dhruv Umraliya 14 37 lokesh 14 38 Amanpalsingh Bhusari 14 39 Karan Sharma 14 40 Jigar Limbasiya 14 41 Deepa Agrawal 14 42 Hasit Parmar 14 43 Naman 14 44 Sandali Ranjan 14 45 S BALAJI 14 46 Vaishnavi P 14 47 Mokshi Gupta 14 48 Bindu 13 49 Sonal borkar 13 50 Varun Aashara 13 51 Amer Khan 13 52 spoorthi kl 13 53 2VD18EC106 13 -

App No Name Dob Caste Code MINDEX Rank 1012859

Provisional Rank List of Govt ITI Idukki-Kanjikuzhy (Admission 2019) App No Name DoB Caste Code MINDEX Rank 1012859 SWARARAJ R 20-May-01 EZ 305 1 1018143 MOHAMED SHEHIN S 28-Aug-00 MU 295 2 1090200 AMAL RAJU 04-Apr-00 EZ 295 3 1052246 THOMAS JOY 05-Nov-00 LC 295 4 1047571 AJAY P MANI 05-Sep-00 SC 290 5 1043584 AKHIL.A 14-May-01 EZ 285 6 1051798 ANANDA KRISHNAN U 17-Sep-01 OC 285 7 1081206 FATHIMA THESNI 03-Sep-01 MU 285 8 1000152 ASWIN DAS 19-Aug-01 OBH 280 9 1054133 SANDRA P K 13-Feb-02 OBH 280 10 1039850 AMBADY GOPI M G 01-Jun-01 OBH 280 11 1095473 NANDUKRISHNA K S 30-Dec-00 OBH 280 12 1062424 RIYAN CLEETUS 01-Nov-00 LC 280 13 1034953 ALTHAF SADATH 15-Aug-00 MU 275 14 1097391 ROHIT BINOY 07-Sep-01 OC 275 15 1051915 ATHUL REMESH 08-Mar-01 OC 275 16 1062117 MIDHUN KUMAR M 23-Sep-98 EZ 275 17 1085608 SHARATH C B 01-Oct-01 OBH 275 18 1033004 ABHILASH M K 08-Dec-01 OBH 275 19 1053169 MIDHUN KA 15-Oct-00 SC 275 20 1067386 SEBASTIAN SHERON 27-Jan-02 LC 275 21 1023456 AKSHAY V KUMAR 08-Feb-01 OC 275 22 1059117 SIDHARTH S S 30-Jun-01 EZ 275 23 1031033 ASHIQ SABITH 10-Oct-01 MU 275 24 1097347 CHRISTY BABU C 31-Oct-01 OC 275 25 1048616 SWAROOP POULOSE 12-Jul-01 OC 270 26 1088695 ALAN A S 28-Aug-00 OBX 270 27 1023476 KARTHIK TP 21-Sep-01 EZ 270 28 1095698 IMMANUEL CHERUVATHUR 10-Nov-01 OC 270 29 1031542 ABHINAND K S 18-Dec-01 OC 270 30 1034396 ANANDHU S 24-Aug-00 EZ 268 31 1037309 ARJUN C 27-May-01 EZ 267 32 1047136 ASHWIN V S 22-Sep-01 EZ 265 33 1057542 MUHAMMAD ALTHAF J 22-Aug-01 MU 265 34 1036752 MANU S KUMAR 17-Dec-01 EZ 265 35 1011037 ASLAM -

Imdb ANNOUNCES the 2019 TOP 10 STARS of INDIAN CINEMA and TELEVISION SERIES AS DETERMINED by PAGE VIEWS

IMDb ANNOUNCES THE 2019 TOP 10 STARS OF INDIAN CINEMA AND TELEVISION SERIES AS DETERMINED BY PAGE VIEWS IMDb 2019 STARmeter Award Winner Priyanka Chopra Jonas Earns the Top Spot on the IMDb Year-End List Rankings Determined by IMDbPro STARmeter Data on the Actual Page Views of the Hundreds of Millions of IMDb Customers Worldwide MUMBAI, INDIA — December 5, 2019 — IMDb (www.imdb.com), the world’s most popular and authoritative source for movie, TV and celebrity content, today unveiled the 2019 Top 10 Stars of Indian cinema and television web series. Rather than base its annual rankings on small statistical samplings, reviews of professional critics, or box office performance, IMDb determines its definitive top 10 lists using data from IMDbPro STARmeter rankings, which are based on the actual page views of the more than 200 million monthly IMDb visitors. 2019 IMDb Fan Favorite STARmeter Award recipient Priyanka Chopra Jonas ranks as this year’s No. 1 top star of Indian cinema and television. And the 2019 winners are: IMDb Top 10 Stars of Indian Cinema and Television in 2019* 1. Priyanka Chopra Jonas 2. Disha Patani 3. Hrithik Roshan 4. Kiara Advani 5. Akshay Kumar 6. Salman Khan 7. Alia Bhatt 8. Katrina Kaif 9. Rakul Preet Singh 10. Sobhita Dhulipala *The 10 stars appearing in 2019 Indian films or television web series who consistently ranked highest on the IMDbPro weekly STARmeter chart throughout the year. IMDbPro STARmeter rankings are based on the actual page views of the more than 200 million monthly visitors to IMDb. To learn more about top rated and trending Indian movies, go to www.imdb.com/india.