The Question of Uniqueness in the Teaching of Jesus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Places of the Passion Pilates' Judgement Hall March 24, 2021

Places of the Passion Pilates’ Judgement Hall March 24, 2021 Places of the Passion Pilates’ Judgement Hall March 24, 2021 AS WE GATHER In this service for Week 5 of Lent, the place of the Passion is Pilate’s Judgment Hall, where Pilate is positioned here to set Jesus free, but turns him over to be crucified in- stead. We are called to remember that the judgment that should have been placed on us was placed on him that we might be free. The meaning, history and spiritual inspira- tion associated with Pilate’s Judgment Hall help us to grow to understand more deeply the hard road our Lord took that the way to heaven might be open to us. PRESERVICE SONG: “Amazing Grace (My Chains Are Gone)” WELCOME OPENING HYMN: “How Deep the Father’s Love for Us” Verse 1 How deep the Father's love for us, How vast beyond all measure That He should give His only Son To make a wretch His treasure. How great the pain of searing loss. The Father turns His face away As wounds which mar the Chosen One Bring many sons to glory. Verse 2 Behold the Man upon a cross, My sin upon His shoulders. Ashamed, I hear my mocking voice Call out among the scoffers. It was my sin that held Him there Until it was accomplished; His dying breath has brought me life. I know that it is finished. Verse 3 I will not boast in anything: No gifts, no pow’r, no wisdom. But I will boast in Jesus Christ: 2 His death and resurrection. -

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ROOTS of CHRISTIANITY, 2ND EDITION Vii

The Ancient Egyptian Roots of Christianity Expanded Second Edition Moustafa Gadalla Maa Kheru (True of Voice) Tehuti Research Foundation International Head Office: Greensboro, NC, U.S.A. The Ancient Egyptian Roots of Christianity Expanded Second Edition by MOUSTAFA GADALLA Published by: Tehuti Research Foundation (formerly Bastet Publishing) P.O. Box 39491 Greensboro, NC 27438 , U.S.A. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recorded or by any information storage and retrieVal system with-out written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. This second edition is a reVised and enhanced edition of the same title that was published in 2007. Copyright 2007 and 2016 by Moustafa Gadalla, All rights reserved. Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gadalla, Moustafa, 1944- The Ancient Egyptian Roots of Christianity / Moustafa Gadalla. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. Library of Congress Control Number: 2016900013 ISBN-13(pdf): 978-1-931446-75-4 ISBN-13(e-book): 978-1-931446-76-1 ISBN-13(pbk): 978-1-931446-77-8 1. Christianity—Origin. 2. Egypt in the Bible. 3. Egypt—Religion. 4. Jesus Christ—Historicity. 5. Tutankhamen, King of Egypt. 6. Egypt—History—To 640 A.D. 7. Pharaohs. I. Title. BL2443.G35 2016 299.31–dc22 Updated 2016 CONTENTS About the Author vii Preface ix Standards and Terminology xi Map of Ancient Egypt xiii PART I : THE ANCESTORS OF THE CHRIST KING Chapter 1 -

“Places of the Passion: Pilate's Judgment Hall”

March 21, 2021 “PLACES OF THE PASSION: PILATE’S JUDGMENT HALL” Sunday, March 21, 2021 9:00AM Worship Service AS WE GATHER In this service for Week 5 of Lent, the place of the Passion is Pilate’s Judgment Hall, where Pilate is positioned here to set Jesus free, but turns him over to be crucified instead. We are called to remember that the judgment that should have been placed on us was placed on him that we might be free. The meaning, history and spiritual inspiration associated with Pilate’s Judgment Hall help us to grow to understand more deeply the hard road our Lord took that the way to heaven might be open to us. Sit OPENING HYMN “Christ, the Life of All the Living” LSB 420 sts. 1-4 1 Christ, the life of all the living, Christ, the death of death, our foe, Who, Thyself for me once giving To the darkest depths of woe: Through Thy suff’rings, death, and merit I eternal life inherit. Thousand, thousand thanks shall be, Dearest Jesus, unto Thee. 2 Thou, ah! Thou, hast taken on Thee Bonds and stripes, a cruel rod; Pain and scorn were heaped upon Thee, O Thou sinless Son of God! Thus didst Thou my soul deliver From the bonds of sin forever. Thousand, thousand thanks shall be, Dearest Jesus, unto Thee. 3 Thou hast borne the smiting only That my wounds might all be whole; Thou hast suffered, sad and lonely, Rest to give my weary soul; Yea, the curse of God enduring, Blessing unto me securing. -

The New Testament at the Time of the Egyptian Papyri. Reflections Based on P12, P75 and P126 (P

The New Testament at the Time of the Egyptian Papyri. Reflections Based on P12, P75 and P126 (P. Amh. 3b, P. Bod. XIV-XV and PSI 1497) Claire Clivaz To cite this version: Claire Clivaz. The New Testament at the Time of the Egyptian Papyri. Reflections Based on P12, P75 and P126 (P. Amh. 3b, P. Bod. XIV-XV and PSI 1497). Claire Clivaz; Jean Zumstein; Jenny Read-Heimerdinger; Julie Paik. Reading New Testament Papyri in Context - Lire les papyrus du Nouveau Testament dans leur contexte. Actes du colloque des 22-24 octobre 2009 à l’université de Lausanne, BETL 242, Peeters, p. 17-55, 2011, 978-90-429-2506-9. hal-02616341 HAL Id: hal-02616341 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02616341 Submitted on 6 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License I. PAPYROLOGY AND THE NEW TESTAMENT THE NEW TESTAMENT AT THE TIME OF THE EGYPTIAN PAPYRI REFLECTIONS BASED ON P12, P75 AND P126 (P.AMH. 3B, P.BOD. XIV-XV AND PSI 1497)1 “Si vous ne dédaignez point de parcourir ce papyrus égyptien sur lequel s’est promenée la pointe d’un roseau du Nil…” Apuleius, Metamorphoses I.1,1 The time has come for manuscripts to play a greater part in New Tes- tament exegesis. -

Svensk Exegetisk 81 Årsbok

SVENSK EXEGETISK 81 ÅRSBOK På uppdrag av Svenska exegetiska sällskapet utgiven av Göran Eidevall Uppsala 2016 Svenska exegetiska sällskapet c/o Teologiska institutionen Box 511, S-751 20 UPPSALA, Sverige www.exegetiskasallskapet.se Utgivare: Göran Eidevall ([email protected]) Redaktionssekreterare: Tobias Hägerland –2016 ([email protected]) David Willgren 2017– ([email protected]) Recensionsansvarig: Rosmari Lillas-Schuil ([email protected]) Redaktionskommitté: Göran Eidevall ([email protected]) Rikard Roitto ([email protected]) Blaåenka Scheuer ([email protected]) Cecilia Wassén ([email protected]) Prenumerationspriser: Sverige: SEK 200 (studenter SEK 100) Övriga världen: SEK 300 Frakt tillkommer med SEK 50. För medlemmar i SES är frakten kostnadsfri. SEÅ beställs hos Svenska exegetiska sällskapet via hemsidan eller postadress ovan, eller hos Bokrondellen (www.bokrondellen.se). Anvisningar för medverkande åter- finns på hemsidan eller erhålls från redaktionssekreteraren. Manusstopp är 1 mars. Tidskriften är indexerad i Libris databas (www.kb.se/libris/). SEÅ may be ordered from Svenska exegetiska sällskapet either through the homepage or at the postal address above. Instructions for contributors are found on the homep- age or may be requested from the editorial secretary (david.willgren@ altutbildning.se). This periodical is indexed in the ATLA Religion Database®, published by the Ameri- can Theological Library Association, 300 S. Wacker Dr., Suite 2100, Chicago, IL 60606; E-mail: [email protected]; WWW: https://www.atla.com/. Omslagsbild: Odysseus och sirenerna (attisk vas, ca 480–470 f.Kr., British Museum) Bildbearbetning: Marcus Lecaros © SEÅ och respektive författare ISSN 1100-2298 Uppsala 2016 Tryck: Bulls Graphics, Halmstad Innehåll Exegetiska dagen 2015/Exegetical Day 2015 Bruce Louden Agamemnon and the Hebrew Bible ...................... -

The Gospel According to Mark -- Chapter 3 of "From Crisis to Christ: a Contextual Introduction to the New Testament" Paul N

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies College of Christian Studies 2014 The Gospel According to Mark -- Chapter 3 of "From Crisis to Christ: A Contextual Introduction to the New Testament" Paul N. Anderson George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Paul N., "The Gospel According to Mark -- Chapter 3 of "From Crisis to Christ: A Contextual Introduction to the New Testament"" (2014). Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies. Paper 104. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs/104 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Christian Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 3 Ίhe Gospel According to Mark Begin with the text. Read the Gospel of Mark, and note important themes and details that come to mind. Author: traditionally, John Mark of Alexandria, the former companion of Paul Audience: believers ίη Jesus among Greek-speaking audiences Time: ca. 70 CE, around the time of the destruction of the temple ίη Jerusalem Place: possibly Rome or another setting in the Gentile mission Message: Ίhe kingdom of God is at hand; turn around, believe, and fol low Jesus. Ίhe Gospel of Mark describes the ministry and message of Jesus with a great sense of urgency. -

Places of the Passion a Series of Services for the Season of Lent PRELUDE "All Glory, Laud and Honor" Sanborn "Christ's Triumphant Ride Into Jerusalem" Bender

St. Luke’s Lutheran Church March 28, 2021 Palm Sunday Image by Daren Hastings. All rights reserved. Places of the Passion A Series of Services for the Season of Lent PRELUDE "All Glory, Laud and Honor" Sanborn "Christ's Triumphant Ride Into Jerusalem" Bender WEEK 6: PILATE'S JUDGEMENT HALL Matthew 27:22 Pilate said to them, “Then what shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?” They all said, “Let him be crucified!” INVOCATION AND CALL TO WORSHIP Pastor: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God the Father, and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all. Cong.: Amen. Pastor: Let us ever walk with Jesus. Cong.: To see the depths of his love. Pastor: To behold the gift of his forgiveness. Cong.: To gaze upon the heights of his grace. Pastor: To marvel at the magnitude of his mercy. Cong.: We walk with Jesus to Pilate’s judgment hall. Pastor: To hear about Jewish leaders, a prisoner named Barabbas and even Pilate’s wife. Cong.: It all boils down to three words—innocent, guilty and free. Pastor: Faithful Lord, with me abide. Cong.: I shall follow where you guide! PROCESSIONAL HYMN “All Glory Laud and Honor” LSB 442, sts. 1, 4–5 CONFESSION AND FORGIVENESS Pastor: Forgiving Father, though I don’t like to admit it, I am a sinner, much like Barabbas— Cong.: A rebel and a wretch. Pastor: Born dead in transgressions and sins. Cong.: Lost and without hope. Pastor: Doomed to perish. Cong.: Blinded by the god of this age. -

For Our 7:00 Pm Divine Service

FOR OUR 7:00 P.M. DIVINE SERVICE Lenten Midweek VI March 24,2021 INI (Please turn off cell phones in preparation for the Divine Service) Places of the Passion : Pilate’s Judgment Hall “Pilate said to them, “Then what shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?” They all said, “Let him be crucified!”” Matthew 27:22 PRELUDE PASTORAL GREETING INVOCATION AND CALL TO WORSHIP P The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God the Father, and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all. C Amen. P Let us ever walk with Jesus. C To see the depths of His love. P To behold the gift of His forgiveness. C To gaze upon the heights of His grace. P To marvel at the magnitude of His mercy. C We walk with Jesus to Pilate’s judgment hall. P To hear about Jewish leaders, a prisoner named Barabbas and even Pilate’s wife. C It all boils down to three words—innocent, guilty and free. P Faithful Lord, with me abide. C I shall follow where you guide! 1 | P a g e HYMN Let Us Ever Walk with Jesus TLH 409 vv.1,2 1. Let us ever walk with Jesus, Follow His example pure, Flee the world, which would deceive us And to sin our souls allure. Ever in His footsteps treading, Body here, yet soul above, Full of faith and hope and love, Let us do the Father's bidding. Faithful Lord, abide with me; Savior, lead, I follow Thee. -

Frescoes of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, the Apostles, Evangelists, Prophets

SACRED SIGHTS Frescoes of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, the Apostles, evangelists, prophets, and angels adorn the walls of the church of the Red Monastery, built in the late fifth century A.D. as part of the flowering of Coptic culture in Egypt. PEDRO COSTA GOMES COPTIC CHRISTIANITY IN ANCIENT EGYPT Christianity’s origins in the ancient world are found in many places, but perhaps the most surprising are in Egypt, where the new faith took root and flourished shortly after the death of Jesus. JOSÉ PÉREZ-ACCINO SAFETY IN EGYPT In this detail of a 13th-century Coptic manuscript, the Flight into Egypt (top right) is depicted. This episode is of particular importance to Copts, who revere the places in Egypt where they believe the Holy Family wandered. AKG/ALBUM gypt, land of the pyramids, is the set- who wanted to kill the child.The family stays in ting for many of the best known tales Egypt until the danger has passed. fromtheOldTestament.ThroughMo- In addition to its important place in Scripture, ses, God punishes the Egyptian pha- Egypt was a fertile garden in the early flowering E A.D. raoh for holding the Hebrew people in of Christianity.From the first century ,as the bondage.Betrayed by his brothers,young Joseph faith took root and began to grow,Egypt became suffers in slavery in Egypt before rising to be- an important religious center, as theologians come vizier, second in power only to Pharaoh. and scholars flocked there.Egyptian Christian- When turning to the New Testament, ity developed its own distinctive flavor,shaped many people think of the lands of Israel by the words, culture, and history of ancient and Palestine, the places where Jesus was Egypt. -

Tiberiana 4: Tiberius the Wise

1 Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Tiberiana 4: Tiberius the Wise Version 1.0 July 2007 Edward Champlin Princeton University Abstract: Abstract: This is one of five parerga preparatory to a book to be entitled Tiberius on Capri, which will explore the interrelationship between culture and empire, between Tiberius’ intellectual passions (including astrology, gastronomy, medicine, mythology, and literature) and his role as princeps. These five papers do not so much develop an argument as explore significant themes which will be examined and deployed in the book in different contexts. This paper examines the extraordinary but scattered evidence for a contemporary perception of Tiberius as the wise and pious old monarch of folklore. © Edward Champlin. [email protected] 2 Tiberius the Wise I The paranoia and cruelty of the aged tyrant in his island fastness are stunningly captured in the horrific tale of the fisherman: A few days after he reached Capreae and was by himself, a fisherman appeared unexpectedly and offered him a huge mullet; whereupon in his alarm that the man had clambered up to him from the back of the island over rough and pathless rocks, he had the poor fellow’s face scrubbed with the fish. And because in the midst of his torture the man thanked his stars that he had not given the emperor an enormous crab that he had caught, Tiberius had his face torn with the crab also. Suetonius Tiberius 601 Inevitably the tale has been conflated with the charge that Tiberius had the victims of his tortures thrown into the sea below (Suetonius 62. -

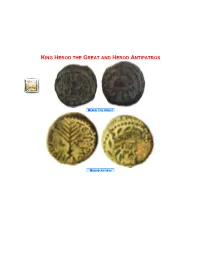

Herod Agrippa I Would Be King Over the Territories Formerly Ruled by Philip and Lysanias, to Which the Tetrarchy of Antipas Would Be Added and Then Judaea and Samaria

KING HEROD THE GREAT AND HEROD ANTIPATROS HEROD THE GREAT HEROD ANTIPAS HDT WHAT? INDEX HEROD ANTIPATROS KING HEROD 73 BCE At about this point Herod the Great was born as the 2d son of Antipater the Idumaean and Cypros, a Nabatean. “NARRATIVE HISTORY” IS FABULATION, HISTORY IS CHRONOLOGY HDT WHAT? INDEX KING HEROD HEROD ANTIPATROS 48 BCE Antipater the Idumaean sent his older son Phasael to Judaea to be governor of Jerusalem and his younger son Herod (who would come to be known as “Herod the Great”) to be governor of nearby Galilee. Cleopatra was removed from power by Theodotas and Achillas. HDT WHAT? INDEX HEROD ANTIPATROS KING HEROD “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY HDT WHAT? INDEX KING HEROD HEROD ANTIPATROS 43 BCE At about this point Lucius Munatius Plancus was directed by the Roman senate to found, at what would become the city of Lyon, a town called Lugdunum. Antipater the Idumaean granted financial support to the murderers of Julius Caesar, an act which brought chaos, and then was poisoned. Herod the Great, with the support of the Roman Army, executed his father’s poisoner. When Antigonus attempted to seize the throne from his uncle Hyrcanus, Herod the Great defeated him (without, however, managing to capture and kill him) and then, to secure for himself a claim to the throne, took Hyrcanus’s teenage niece, Mariamne (known as Mariamne I), to wife. Inconveniently, he already had a wife, named Doris, and a three-year-old son, named Antipater III — and so he banished both of them. -

The Shocking Truth About You, Me and Barabbas

The Shocking Truth about You, Me and Barabbas This amazing hidden truth in the Easter story will turn your life upside down! Berni Dymet Life Applicaton Booklet THE SHOCKING TRUTH ABOUT YOU, ME AND BARABBAS by Berni Dymet LIFE APPLICATION BOOKLET Published by Christianityworks © Berni Dymet 1st edition - Published 2019 Except where otherwise indicated in the text, the scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design: Mariah Reilly Design, Sydney Australia We gratefully acknowledge the creative contribution of Mariah Reilly in the cover design of this book. Printed by: Creative Visions Print & Design, Warrawong, NSW, Australia No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means - electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise - without prior written permission . Christianityworks Australia: PO Box 1729 BONDI JUNCTION NSW 1355 p: 1300 722 415 India: PO Box 1602 SECUNDERABAD - 500 003 Andhra Pradesh p: 91-9866239170 e: [email protected] w: christianityworks.com e: [email protected] CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Let’s Tarry for a While 5 CHAPTER 2 An Innocent Man 17 CHAPTER 3 Who is Barabbas? 31 THIS BOOKLET IS OUR FREE GIFT TO YOU Thank you for your generous support in making it freely available to others CHAPTER 1 Let’s Tarry for a While It’s interesting how quickly Easter passes us by, how quickly we forget it and move on.