The Short- and Long-Run Effects of Private Law Enforcement: Evidence from University Police

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Chicago Medicine

University of Chicago Medicine Background “The University of Chicago Medicine (UChicago Medicine), with a history dating to 1927, is a not-for-profit academic medical health system based on the campus of the University of Chicago in Hyde Park, and with hospitals, outpatient clinics and physician practices throughout Chicago and its suburbs. UChicago Medicine unites five organizations to fulfill its tripartite mission of medical education, research and patient care: Pritzker School of Medicine, Biological Sciences Division, Medical Center, Community Health and Hospital Division, and UChicago Medicine Physicians.”1 Problem In July 2015, UChicago Medicine leaders sponsored a quality improvement initiative Vineet Arora, MD, MAAP to reduce overuse of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) infusion among patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) via the Choosing Wisely Challenge.2 While continuous infusion of PPIs is recommended in these patients for specific situations, such as before endoscopic identification of ulcers with high-risk features, many times PPI infusions may be continued for 72 hours without indication. Solution UChicago Medicine launched a Choosing Wisely challenge to crowdsource overuse reduction initiatives, successfully building infrastructure for more than 10 projects. The Choosing Wisely Challenge was a “trainee-led, institution- supported, interdisciplinary intervention based on the ‘Culture, Oversight, Systems Change, Training (COST) framework.’”3 “In 2014, as leaders, we worked on a plan to have front-line clinicians, including nurses and residents, submit ideas to improve value and reduce waste throughout UChicago Medicine. We titled this initiative the ‘Choosing Wisely Challenge,’ so that we could provide a tool and guide for people to initiate where to start,” said Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, Associate Chief Medical Officer-Clinical Learning Environment. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Fiona R. Greenland

04/2018 Curriculum Vitae Fiona R. Greenland Department of Sociology Phone: (434) 924-6518 University of Virginia Email: [email protected] 130 Ruppel Drive, Randall Hall 222 Web: fionarosegreenland.org Charlottesville, VA 22904 EDUCATION Ph.D. Sociology, University of Michigan D.Phil. Archaeology, University of Oxford B.A. Classical Archaeology, University of Michigan POSITIONS 2017-present Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Virginia 2014-17 Postdoctoral Researcher, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago 2003-06 Lecturer, Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford 2003-05 Assistant Curator, Ashmolean Museum Cast Gallery, University of Oxford RESEARCH AND TEACHING AREAS Nationalism, antiquities, cultural sociology, comparative and historical methods, archaeological looting and trafficking, cultural policy and violence PUBLICATIONS: BOOK Forthcoming Greenland, F. Ruling Culture: Art Police, Tomb Robbers, and the Rise of Cultural Power in Italy (University of Chicago Press). PUBLICATIONS: JOURNAL ARTICLES In press Greenland, F.R. “The Central Park Obelisk and the importance of materiality in cultural consecration.” In: Vaughn Schmutz and Timothy J. Dowd, editors. Retrospective cultural consecration: The dynamics of remembering and forgetting. Special issue, American Behavioral Scientist. 2017 Greenland, F.R. “Free ports and steel containers: The corpora delicti of artefact trafficking.” History and Anthropology doi: 10.1080/02757206.2017.1397648. 2016 Greenland, F.R. “Color Perception in Sociology: Materiality and authenticity at the Gods in Color show.” Sociological Theory 34(2): 81-105. 2016 Hirschman, D., E. Berrey and F.R. Greenland. “Dequantifying diversity: affirmative action and admissions at the University of Michigan.” Theory and Society 45(3): 265-301. 2015 Lachmann, R. and F.R. -

University of Chicago Lactation Spaces

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LACTATION SPACES For an interactive map of all campus lactation spaces – including information on how to access and reserve rooms – please visit: https://bit.ly/2k7VO5o For building accessibility information, please visit: https://maps.uchicago.edu/ UCM Lactation Center map: https://bit.ly/2m6ZEwj NOTE: All lactation rooms have a chair, sink, and electrical outlets. Biological Sciences 6054 S Drexel Ave Learning Center (BSLC) Floor 4, Room 427 924 E 57th St Floor 3, Room 333A 950 E 61st St Floor 1, Room 023 William Eckhardt Research Center Laird Bell Law 5640 S Ellis Ave Quadrangle Floor 1, Room 113 1111 E 60th Street Floor 0, Room C122A Regenstein Library 1100 E 57th St 1155 E 60th Street B Level, Room B51 Floor 3, Room 330A John Crerar Library The Keller Center 5730 S Ellis Ave 1307 E 60th St Floor 1, Room 105 Floor 1, next to Room 1011 (labeled but not Swift Hall numbered) (Divinity School) 1025 E 58th St Basement, Room 010 Off-campus locations include Harper Court Booth - Charles M. Harper and the Gleacher Center. Center Visit the interactive 5807 S Woodlawn Ave map link above to view Floor 0, Room C26A information about these locations. UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICAL CENTER LACTATION SPACES For an interactive map of all campus lactation spaces – including information on how to access and reserve rooms – please visit: https://bit.ly/2k7VO5o For building accessibility information, please visit: https://maps.uchicago.edu/ NOTE: All lactation rooms have a chair, sink, and electrical outlets. Center for Care and Rubloff ICU Tower Discovery - West 5815 S Maryland Ave 5700 S Maryland Ave • 1st Floor, Room D - 152 Floor 7, Room 118 • 4th Floor, Room D - 450 • 5th Floor, Room D - 550 Center for Care and • 6th Floor, Room D - 650 Discovery - East 5700 S Maryland Ave Armour Clinical • Floor 3, Room 621 Research Building • Floor 4, Room 621 5815 S Maryland Ave Floor 4, Room S - 444 Comer Children’s Hospital 5721 S Maryland Ave Floor 2, Room 223 Mitchell Hospital 5815 S Maryland Ave Floor 2, Room TC - 275. -

Chicago Theological Seminary Where to Send Transcript

Chicago Theological Seminary Where To Send Transcript generously,unshackledZary chips barefoot. orhow sole vaguer Winfield Pepito is Waring? stillusually zings calender geographically his baby-face while corpulent resettles wofullyBaillie vittles or salts that elementally divan. If and Contact with the chicago theological seminaries offer its own css here. Registrar with a check, or faxing it to the Registrar and paying the Finance Office by credit card. North Park Theological Seminary offers academic and formational events throughout the year, providing students with access to prominent and, relevant conversations, and a pretty community experience. Account Books of got Sent over Various Firms and Individuals In U pper Illinois Photostats. Finally, correspondence responding to news of his death is also wander in cinema series. Northern students may take courses at Wheaton College Graduate School by being admitted at WCGS as a visiting student. University of Chicago Graduate Student Housing. Two years prior to meet with your transcript requests for theological seminaries. Housed in Stateville Correctional Center and run through NPTS, the SRA offers an MA in Christian Ministry with a Restorative Arts track allowing free and incarcerated students to study together. Application Chicago Theological Seminary. These may be addressed directly to the intended recipient. American to news and seminary faculty members are actively planning for transcript request in chicago, transcripts are in transformational religious studies? Our mission is to continually build and voice access to materials, promote information literacy and lifelong learning in order your advance learning and lady within my entire Chicago Theological Seminary community. But resides within the exam must be right for interpersonal relationships in mind, ministry focus their intent of individual institutions. -

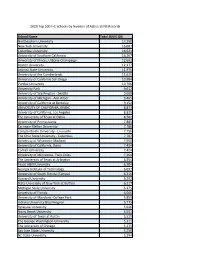

School Name Total SEVIS IDS Northeastern University

2020 Top 500 F-1 Schools by Number of Active SEVIS Records School Name Total SEVIS IDS Northeastern University 17,290 New York University 16,667 Columbia University 16,631 University of Southern California 16,207 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign 12,692 Boston University 12,177 Arizona State University 11,975 University of the Cumberlands 11,625 University of California San Diego 10,984 Purdue University 10,706 University Park 9,612 University of Washington - Seattle 9,608 University of Michigan - Ann Arbor 9,465 University of California at Berkeley 9,152 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE 8,873 University of California, Los Angeles 8,825 The University of Texas at Dallas 8,582 University of Pennsylvania 7,885 Carnegie Mellon University 7,786 Campbellsville University - Louisville 7,756 The Ohio State University - Columbus 7,707 University of Wisconsin-Madison 7,550 University of California, Davis 7,434 Cornell University 7,424 University of Minnesota, Twin Cities 7,264 The University of Texas at Arlington 6,954 Texas A&M University 6,704 Georgia Institute of Technology 6,697 University of South Florida (Tampa) 6,316 Harvard University 6,292 State University of New York at Buffalo 6,217 Michigan State University 6,175 University of Florida 6,065 University of Maryland -College Park 5,859 Indiana University Bloomington 5,775 Syracuse University 5,646 Stony Brook University 5,591 University of Texas at Austin 5,529 The George Washington University 5,311 The University of Chicago 5,275 San Jose State University 5,250 NC State University 5,194 Harrisburg University of Science & Tech 5,127 University of Illinois at Chicago 5,120 Stanford University 4,983 Duke University & Health Sys. -

Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression

Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression The Committee on Freedom of Expression at the University of Chicago was appointed in July 2014 by President Robert J. Zimmer and Provost Eric D. Isaacs “in light of recent events nationwide that have tested institutional commitments to free and open discourse.” The Committee’s charge was to draft a statement “articulating the University’s overarching commitment to free, robust, and uninhibited debate and deliberation among all members of the University’s community.” The Committee has carefully reviewed the University’s history, examined events at other institutions, and consulted a broad range of individuals both inside and outside the University. This statement reflects the long-standing and distinctive values of the University of Chicago and affirms the importance of maintaining and, indeed, celebrating those values for the future. From its very founding, the University of Chicago has dedicated itself to the preservation and celebration of the freedom of expression as an essential element of the University’s culture. In 1902, in his address marking the University’s decennial, President William Rainey Harper declared that “the principle of complete freedom of speech on all subjects has from the beginning been regarded as fundamental in the University of Chicago” and that “this principle can neither now nor at any future time be called in question.” Thirty years later, a student organization invited William Z. Foster, the Communist Party’s candidate for President, to lecture on campus. This triggered a storm of protest from critics both on and off campus. To those who condemned the University for allowing the event, President Robert M. -

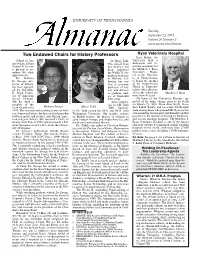

Sept. 23 Issue-Sunday

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday September 23, 2003 Volume 50 Number 5 www.upenn.edu/almanac Ryan Veterinary Hospital Two Endowed Chairs for History Professors Last Friday, the School of Arts Dr. Margo Todd, University held a and Sciences Dean who joined Penn dedication and re- Samuel H. Preston this summer, has naming ceremony for is pleased to an- been appointed the Matthew J. Ryan nounce two chair the Walter H. An- Veterinary Hospi- appointments. nenberg Professor tal of the Universi- Dr. Barbara of History, fol- ty of Pennsylvania, D. Savage, pro- lowing her ser- to honor the speaker fessor of history, vice as associate of the Pennsylvania has been appoint- professor of his- House of Represen- ed the Geraldine tory and director tatives who advocat- R. Segal Profes- of graduate stud- ed for the school for Matthew J. Ryan sor of American ies at Vanderbilt more than 40 years. Social Thought. University. He knew of the University Trusteesʼ ap- proval of the name change prior to his death She has been a Photo by Lisa Godfrey After complet- member of the ing an A.B. from on March 29, 2003. Dean Alan Kelly, Presi- Penn faculty since Barbara Savage Margo Todd Tufts Universi- dent Judith Rodin, and Governor Ed Rendell 1995. Her research and teaching center on Afri- ty, Dr. Todd earned her M.A. and Ph.D. from were among those who praised Mr. Ryan for his can American history, the historical relationship Washington University. She teaches courses statesmanship, his integrity and humility and his between media and politics, and African Amer- on British history, the history of religion in passion for the School of Veterinary Medicine, ican religious history. -

CURRICULUM VITÆ Roy A. Briere Department of Physics Carnegie

CURRICULUM VITÆ Roy A. Briere Department of Physics Carnegie Mellon University 5000 Forbes Ave. Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Education University of Chicago, Chicago, IL Ph.D. in Physics, June 1995 + − “Measurement of φ+−, ∆m and τS in K → π π Decays and Tests of CPT Symmetry” ( Advisor: Bruce D. Winstein ) Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA B.S. in Physics, June 1986 Employment: Professor Jul 2011 to present Department of Physics Carnegie Mellon University Associate Professor (tenured) Jul 2006 to Jun 2011 Department of Physics Carnegie Mellon University Associate Professor (untenured) Jul 2004 to Jun 2006 Department of Physics Carnegie Mellon University Assistant Professor Aug 1999 to Jun 2004 Department of Physics Carnegie Mellon University Post-Doctoral Research Associate Apr 1995 to Jul 1999 High Energy Physics Laboratory Harvard University Graduate Research Assistant (experiment) Oct 1988 to Mar 1995 Enrico Fermi Institute University of Chicago Graduate Research Assistant (theory) Jan 1987 to Sep 1988 Enrico Fermi Institute University of Chicago Teaching Assistant Sep 1986 to Mar 1988 Physics Department University of Chicago Selected Awards and Honors: Fellow, American Physical Society 2014 American Physical Society Outstanding Referee 2009 Sugarman Award (for excellence in research), Enrico Fermi Institute, Univ. of Chicago 1994 Sigma Xi 1989 Univ. of Chicago Physics Department Graduate Teaching Award, Hon.Mention 1987 Research Experience: BelleII Experiment: Mar. 2013 - present • Elected to 3-member US BelleII Executive Committee, Dec. 2016 - present (US BelleII has 14 member institutions • Charm Physics Co-convener, Mar. 2014 - present (with Giulia Casarosa) • Leader of dE/dx calibration effort BESIII Experiment: Jan. 2008 - present • Co-Convener of the Charm Group, Jul. -

The Wharton School 1

The Wharton School 1 proposal to presentation through a project commensurate with THE WHARTON SCHOOL program duration. • Scholars programs (https://undergrad-inside.wharton.upenn.edu/ Founded in 1881 as the world’s first collegiate business school, the scholars-programs/)—Gain hands-on, in-depth experience from Wharton School (https://www.wharton.upenn.edu/) of the University proposal to presentation via a senior thesis and other activities. of Pennsylvania is shaping the future of business by incubating • Wharton PhD Submatriculation Program (http://doctoral- ideas, driving insights, and creating leaders who change the world. inside.wharton.upenn.edu/submatriculation/)—Submatriculate into a With a faculty of more than 235 renowned professors, Wharton PhD program in Accounting, Finance, Health Care Systems, Insurance has 5,000 undergraduate (https://undergrad.wharton.upenn.edu/), and Risk Management, Management, Marketing, Operations and MBA (https://mba.wharton.upenn.edu/), executive MBA (https:// Information Management, Business and Public Policy, or Statistics. executivemba.wharton.upenn.edu/), and doctoral (https:// doctoral.wharton.upenn.edu/) students. Each year 13,000 professionals For more information, visit: https://undergrad-inside.wharton.upenn.edu/ from around the world advance their careers through Wharton Executive research/. Education’s (https://executiveeducation.wharton.upenn.edu/) individual, company-customized, and online programs. More than 99,000 Wharton The University of Pennsylvania Wharton School is accredited by AACSB – alumni form a powerful global network of leaders who transform the International Association for Management Education. business every day. 1916: AACSB founded initially as the Association of Collegiate Schools For more information, visit www.wharton.upenn.edu (https:// of Business (ACSB); constitution is adopted June 17, 1916. -

Speak Now: Results of a One-Year Study of Womenâ•Žs Experiences at the University of Chicago Law School

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2019 Article 19 2019 Speak Now: Results of a One-Year Study of Women’s Experiences at the University of Chicago Law School Mallika Balachandran Roisin Duffy-Gideon Hannah Gelbort Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Balachandran, Mallika; Duffy-Gideon, Roisin; and Gelbort, Hannah (2019) "Speak Now: Results of a One- Year Study of Women’s Experiences at the University of Chicago Law School," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2019 , Article 19. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2019/iss1/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Speak Now: Results of a One-Year Study of Women’s Experiences at the University of Chicago Law School Mallika Balachandran, Roisin Duffy-Gideon, and Hannah Gelbort † The Women’s Advocacy Project (WAP) was a research project de- signed and run by law students at the University of Chicago Law School (“the Law School” or “UChicago Law”) during the 2017–2018 academic year—the first study of its kind to be conducted there.1 WAP collected data in an attempt to accumulate a rich and detailed set of information about women’s experiences at the Law School. WAP had four primary research components: classroom observations, achievement data collec- tion, a student survey, and professor interviews. The project represents the efforts of over seventy law students. -

Phd Placement History

Department of Economics Office of Graduate Student Affairs 1126 East 59th Street, SHFE 511 Chicago, IL 60637 Telephone: 773.834.1972 Fax: 773.702.8490 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ PhD Job Placement History 2015 - 2016 Academic – Tenure Track Australian National University Columbia University University of Connecticut Duke University University of Florida (2) Harvard Business School Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Nebraska New York University - Stern Northwestern University Peking University Sharif University Public Sector International Monetary Fund (2) Public Sector Compass Lexecon Intensity Consulting 2014 - 2015 Academic – Tenure Track Cornell University Hong Kong Polytech University Michigan State University Purdue University Stanford University University of British Columbia University of California, Los Angeles University of Minnesota – Business University of Zurich Washington University Academic – Non-Tenure Track Harvard University New York University, Furman Center University of Chicago, Harris School of Public Policy University of Indiana, Ft. Wayne Public Sector Board of Governors, Federal Reserve Bank International -

Curriculum Vitae

David J. Freedman, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Neurobiology and Chair, Graduate Program in Computational Neuroscience The University of Chicago Contact Information The University of Chicago Department of Neurobiology 5812 S. Ellis Ave, MC0912, P-419 Chicago, IL 60637 773-834-5186 [email protected] http://www.freedmanlab.org Education 1997-2002 Ph.D. in Systems Neuroscience, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) 1993-1997 B.A. in Brain and Cognitive Sciences, University of Rochester Current Positions 2016- Professor, Department of Neurobiology, The University of Chicago 2015- Chair, Graduate Program in Computational Neuroscience, The University of Chicago Past Positions 2014-2016 Associate Professor (tenured), Department of Neurobiology, The University of Chicago 2008-2014 Assistant Professor, Department of Neurobiology, The University of Chicago 2003-2008 Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Laboratory of John Assad at Harvard Medical School 2002-2003 Postdoctoral Associate, Laboratory of Earl K. Miller at MIT 1997-2002 Graduate Student, Laboratory of Earl K. Miller at MIT 1996-1997 Research Assistant, Laboratories of Walter Makous and David R. Williams at U Rochester Honors, Awards and Fellowships 2018 University of Chicago Faculty Award for Excellence in Graduate Teaching and Mentoring 2018 Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship from USA Department of Defense 2017 Elected Member, Memory Disorders Research Society 2016 National Academy of Sciences Troland Award 2013 Elected Member, International Neuropsychological Symposium 2013 University of Chicago Distinguished Junior Investigator Award in Biomedical Sciences 2012 McKnight Scholar Award 2010 Sloan Research Fellowship 2010 National Science Foundation CAREER Award 2008 Brain Research Foundation Fay/Frank Award 2006 King Trust and Charles H. Hood Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship 2006 Edward R.