Argentina's Economic Crisis: Causes and Cures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argentina's Economic Crisis

Updated January 28, 2020 Argentina’s Economic Crisis Argentina is grappling with a serious economic crisis. Its Meanwhile, capital inflows into the country to finance the currency, the peso, has lost two-thirds of its value since deficit contributed to an overvaluation of the peso, by 10- 2018; inflation is hovering around 30%; and since 2015 the 25%. This overvaluation also exacerbated Argentina’s economy has contracted by about 4% and its external debt current account deficit (a broad measure of the trade has increased by 60%. In June 2018, the Argentine balance), which increased from 2.7% of GDP in 2016 to government turned to the International Monetary Fund 4.8% of GDP in 2017. (IMF) for support and currently has a $57 billion IMF program, the largest program (in dollar terms) in IMF Crisis and Initial Policy Response history. Despite these resources, the government in late Argentina’s increasing reliance on external financing to August and early September 2019 postponed payments on fund its budget and current account deficits left it some of its debts and imposed currency controls. vulnerable to changes in the cost or availability of financing. Starting in late 2017, several factors created In the October 2019 general election, the center-right problems for Argentina’s economy: the U.S. Federal incumbent President Mauricio Macri lost to the center-left Reserve (Fed) began raising interest rates, reducing investor Peronist ticket of Alberto Fernández for president and interest in Argentine bonds; the Argentine central bank former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner for vice reset its inflation targets, raising questions about its president. -

Representing Different Constituencies: Electoral Rules in Bicameral Systems in Latin America and Their Impact on Political Representation

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Nolte, Detlef; Sánchez, Francisco Working Paper Representing Different Constituencies: Electoral Rules in Bicameral Systems in Latin America and Their Impact on Political Representation GIGA Working Papers, No. 11 Provided in Cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Suggested Citation: Nolte, Detlef; Sánchez, Francisco (2005) : Representing Different Constituencies: Electoral Rules in Bicameral Systems in Latin America and Their Impact on Political Representation, GIGA Working Papers, No. 11, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182554 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, -

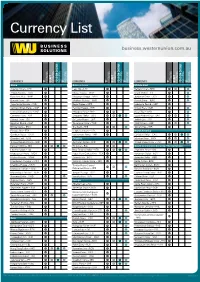

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Argentina: Rudderless

1 110TH CONGRESS " ! S. PRT. 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 110–48 ARGENTINA: RUDDERLESS REPORT TO THE MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 9, 2008 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations Available via World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/ index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 44–239 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 16:39 Sep 11, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 H:\DOCS\44239.TXT sfrela2 PsN: MIKEB seneagle COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., DELAWARE, Chairman CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin NORM COLEMAN, Minnesota BARBARA BOXER, California BOB CORKER, Tennessee BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire BARACK OBAMA, Illinois GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland JIM DEMINT, South Carolina ROBERT P. CASEY, JR., Pennsylvania JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia JIM WEBB, Virginia DAVID VITTER, Louisiana ANTONY J. BLINKEN, Staff Director KENNETH A. MYERS, JR., Republican Staff Director (II) VerDate Aug 31 2005 16:39 Sep 11, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 H:\DOCS\44239.TXT sfrela2 PsN: MIKEB CONTENTS Page Letter of Transmittal ............................................................................................... v Introduction ............................................................................................................. -

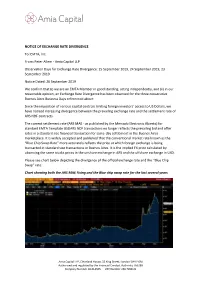

NOTICE of EXCHANGE RATE DIVERGENCE To: EMTA, Inc. From

NOTICE OF EXCHANGE RATE DIVERGENCE To: EMTA, Inc. From: Peter Allem - Amia Capital LLP Observation Days for Exchange Rate Divergence: 25 September 2019, 24 September 2019, 23 September 2019 Notice Dated: 26 September 2019 We confirm that (i) we are an EMTA Member in good standing, acting independently, and (ii) in our reasonable opinion, an Exchange Rate Divergence has been observed for the three consecutive Buenos Aires Business Days referenced above. Since the imposition of various capital controls limiting foreign investors’ access to US Dollars, we have noticed increasing divergence between the prevailing exchange rate and the settlement rate of ARS NDF contracts. The current settlement rate (ARS MAE - as published by the Mercado Electronic Abierto) for standard EMTA Template USDARS NDF transactions no longer reflects the prevailing bid and offer rates in a standard size financial transaction for same-day settlement in the Buenos Aires marketplace. It is widely accepted and published that the conventional market rate known as the “Blue Chip Swap Rate” more accurately reflects the price at which foreign exchange is being transacted in standard size transactions in Buenos Aires. It is the implied FX price calculated by observing the same stocks prices in the onshore exchange in ARS and the offshore exchange in USD. Please see chart below depicting the divergence of the official exchange rate and the “Blue Chip Swap” rate. Chart showing both the ARS MAE Fixing and the Blue chip swap rate for the last several years Amia Capital LLP, Cleveland House, 33 King Street, London SW1Y 6RJ Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 766288 Company Number OC414565 VAT Number 269 7958 22 Chart showing more recent performance of the divergence in FX rates NOTICE OF EXCHANGE RATE DIVERGENCE To: EMTA, Inc. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

Example 4.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I 1 Example4-PesoandUSDollar-ForeignCurrencyConversion(FCC)-MultiplePesoCalculations Page1of2 2 3 Travel Expense Description Date Time Currency Transportation Accommodation Meals Other Receipt / Voucher # 4 Bank Service Charge for 800.00 USD (Traveller's Cheques) 2008-07-02 CAD 5.75 A 5 Airport Currency Exchange Kiosk - Service Charge - 400.00 USD for Columbian Pesos 2008-07-02 CAD 6.00 B 6 TAXI - Depart Home to Ottawa International Airport 2008-07-02 6:00 AM CAD 52.00 C 7 Breakfast - Ottawa International Airport (after airline check-in / security) 2008-07-02 7:00 AM CAD 13.60 N/A 8 Flight 1 - Ottawa to Fort Lauderdale, USA (no meal on flight) 2008-07-02 8:40 AM CAD Prepaid Refer to itinerary document 9 Lunch - Airport - Fort Lauderdale, USA 2008-07-02 12:30 PM USD 12.85 10 Flight 2 - Fort Lauderdale, USA to Bogota, Columbia 2008-07-02 5:00 PM CAD Prepaid Refer to itinerary document 11 Dinner - Served on Flight 2 2008-07-02 CAD Prepaid Refer to itinerary document 12 Arrive Bogotá - Taxi from Airport to Hotel 2008-07-02 8:30 PM COLUMBIAN PESOS 12,710.00 D 13 Incidentals - Day 1 of trip - Appendix C - Incidentals 17.30 CAD 2008-07-02 CAD 17.30 N/A 14 Hotel - Radisson Royal Bogota (272,703.64 Room Rate + 4727.27 taxes) 2008-07-02 COLUMBIAN PESOS 277,430.91 E- Hotel Invoice 15 Breakfast - Bogotá, Columbia - Appendix D - receipt required 2008-07-03 COLUMBIAN PESOS 25,000.00 E-1 (Billed to Room) 16 Lunch - Bogotá, Columbia - Appendix D meal allowance 2008-07-03 COLUMBIAN PESOS 37,700.00 17 Dinner - Bogotá, Columbia - Appendix D - Meal allowance 2008-07-03 COLUMBIAN PESOS 49,500.00 18 Incidentals - Bogotá, Columbia - Appendix D incidental allowance 2008-07-03 COLUMBIAN PESOS 34,880.00 19 Hotel - Radisson Royal Bogota (272,703.64 Room Rate + 4727.27 taxes) 2008-07-03 COLUMBIAN PESOS 277,430.91 E- Hotel Invoice 20 Hotel Front Desk - Service Charge (US Traveller's Cheques to Col. -

The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences Workshop Report

The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences Workshop Report Lima, Peru 23-24 February 2003 © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2003 International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: Information Unit International IDEA SE -103 34 Stockholm Sweden International IDEA encourages dissemination of its work and will promptly respond to requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications. Graphic design by: Magnus Alkmar Cover photos: Anoli Perera, Sri Lanka Printed by: Trydells Tryckeri AB, Sweden ISBN: 91-89578-007 Preface The International Institute for Democracy and tion on quotas, IDEA is convening a series of regio- Electoral Assistance (IDEA), an intergovernmental nal workshops. This report documents the discus- organization with member states across all conti- sion at, and the findings from, the second in the seri- nents, seeks to support sustainable democracy in es, The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American both new and long-established democracies. Experiences, which is to be followed by workshops Drawing on comparative analysis and experience, in Africa, Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, and the IDEA works to strengthen electoral processes, Arab World. The workshop was held in Lima, Peru, enhance political equality and participation and to where IDEA has been operating a country program- develop democratic institutions and practices. The me since 2002. inclusive and responsive nature of those institutions Many individuals and organizations in Peru sup- is considered of particular importance if there is to ported IDEA’s workshop on quotas in Latin be effective governance, benefiting a wide spectrum America, and we are grateful for their enthusiasm of groups in society. -

Currency List

Americas & Caribbean | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ANG Netherland Antillean Guilder ARS Argentine Peso BBD Barbados Dollar BMD Bermudian Dollar BOB Bolivian Boliviano BRL Brazilian Real BSD Bahamian Dollar CAD Canadian Dollar CLP Chilean Peso CRC Costa Rica Colon DOP Dominican Peso GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal GYD Guyana Dollar HNL Honduran Lempira J MD J amaican Dollar KYD Cayman Islands MXN Mexican Peso NIO Nicaraguan Cordoba PEN Peruvian New Sol PYG Paraguay Guarani SRD Surinamese Dollar TTD Trinidad/Tobago Dollar USD US Dollar UYU Uruguay Peso XCD East Caribbean Dollar 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Europe | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ALL Albanian Lek BGN Bulgarian Lev CHF Swiss Franc CZK Czech Koruna DKK Danish Krone EUR Euro GBP Sterling Pound HRK Croatian Kuna HUF Hungarian Forint MDL Moldovan Leu NOK Norwegian Krone PLN Polish Zloty RON Romanian Leu RSD Serbian Dinar SEK Swedish Krona TRY Turkish Lira UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Middle East | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverabl Non-Deliverabl Special Symbol Capability e Forward e Forward requirements/ Restrictions AED Utd. Arab Emir. Dirham BHD Bahraini Dinar ILS Israeli New Shekel J OD J ordanian Dinar KWD Kuwaiti Dinar OMR Omani Rial QAR Qatar Rial SAR Saudi Riyal 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. -

1Q12 Prelease

www.embotelladoraandina.com For immediate distribution Contacts in Santiago, Chile Contacts in the U.S.A. Embotelladora Andina i-advize Corporate Communications, Inc. Andrés Wainer, Cheif Financial Officer Peter Majeski/ Rafael Borja Paula Vicuña, Head of Finance and Investor Relations (212) 406-3690 / [email protected] (56-2) 338-0520 / [email protected] Embotelladora Andina announces Consolidated Results for the First Quarter ended March 31, 2012 All figures included in this analysis, are expressed under IFRS and in nominal Chilean pesos and therefore all variations regarding 2011 are in nominal terms. For a better understanding of the analysis by country, we include a chart based on nominal local currency for the first quarter. Consolidated Sales Volume for the quarter amounted to 143.8 million unit cases, a 10.4% increase. Operating Income for the quarter reached Ch$41,566 million, an increase of 4.7% compared to the previous year. Operating Margin was 14.4%. First quarter EBITDA was Ch$53,483 million, an increase of 9.5%. EBITDA Margin was 18.5%. Net Income for the quarter reached Ch$24,710 million, a decrease of 11.7%. (Santiago-Chile, May 29th 2012) - Embotelladora Andina announced today its consolidated financial results for the First Quarter ended March 31, 2012. Comments from the Chief Executive Officer, Mr. Miguel Ángel Peirano “First quarter results reaffirm the improvement we began to report since the second half of 2011. We grew 10.4% in terms of consolidated volumes during the quarter, with double digit growth rates in Argentina as well as in Chile and a 6.5% growth rate in Brazil, driven by increases in market share of our operations, better weather conditions compared to the previous year, and improved macroeconomic scenarios in the three franchises where we operate. -

I. TOTAL FOREIGN EXCHANGE VOLUME, April 2006 Millions of U.S

I. TOTAL FOREIGN EXCHANGE VOLUME, April 2006 Millions of U.S. Dollars AVERAGE DAILY VOLUME Current Dollar Change Percentage Change Instrument Amount Reported over Previous Year over Previous Year Spot transactions 276,052 85,093a 44.6 Outright forwards 95,619 38,165 66.4 Foreign exchange swaps 157,503 8,403 5.6 OTC foreign exchange options 48,089 6,653 16.1 Total 577,263 138,314a 31.5 TOTAL MONTHLY VOLUME Current Dollar Change Percentage Change Instrument Amount Reported over Previous Year over Previous Year Spot transactions 5,521,016 1,510,884a 37.7 Outright forwards 1,912,480 705,969 58.5 Foreign exchange swaps 3,150,197 19,118 0.6 OTC foreign exchange options 961,882 91,760 10.5 Total 11,545,575 2,327,731a 25.3 Note: The lower table reports notional amounts of total monthly volume adjusted for double reporting of trades between reporting dealers; there were twenty-one trading days in April 2005 and twenty in April 2006. aReflects a revision to the April 2005 data. Survey of North American Foreign Exchange Volume 65 2a. SPOT TRANSACTIONS, Average Daily Volume, April 2006 Millions of U.S. Dollars Counterparty Reporting Other Other Financial Nonfinancial Currency Pair Dealers Dealers Customers Customers Total U.S. DOLLAR VERSUS Euro 21,172 45,168 27,542 5,261 99,143 Japanese yen 10,624 18,840 14,310 2,696 46,470 British pound 5,536 11,981 8,939 1,762 28,218 Canadian dollar 4,040 6,334 3,336 1,646 15,356 Swiss franc 3,686 7,025 7,300 889 18,900 Australian dollar 2,214 4,332 2,798 638 9,982 Argentine peso 34 52 43 12 141 Brazilian real 643 1,309 710 239 2,901 Chilean peso 172 344 130 39 685 Mexican peso 2,220 3,338 1,750 2,107 9,415 All other currencies 2,115 4,780 4,296 2,180 13,371 EURO VERSUS Japanese yen 2,255 4,312 2,748 424 9,739 British pound 1,410 2,855 1,076 508 5,849 Swiss franc 1,483 3,169 1,678 344 6,674 ALL OTHER CURRENCY PAIRS 1,958 4,003 1,776 1,471 9,208 Totala 59,562 117,842 78,432 20,216 276,052 2b.