{PDF EPUB} Which One Am I Multiple Personalities and Deep Southern Secrets by Thomas S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oct 2008 Master

The Patriot Issue 1 Washington Township High School, Sewell, NJ October 2008 Something to cheer about Contract issues in past, WTHS returns to normal Katie Mount ‘09 With the turbulent, 2007-8 school year behind, the students and staff of Washington Township High School are looking forward to what they hope will be a smoother one. “The 2008 school year began very smoothly,” WTHS Principal Rosemarie Farrow said. “... our students, expecially the seniors, seemed very excited to be off and running.” Last year, WTHS was negatively affected by the teacher negotiation dilemma. When the Board of Education and the Teahcer’s Association reached a stalemate, the Washington Township Education Association (WTEA) decided that the members would not volunteer for school events. Their attempt was to draw attention to the negotiation problem, but in doing so, many students were affected. Many activities were cancelled, and many students were disappointed. Now, with the contract issue solved, many staff Gina Parker ‘09/The Patriot members are again stepping forward to volunteer. Students share the good times as they display school spirit at a recent football game. “I’m glad that teachers are volunteering junior and senior girls do the playing, and the of volunteers. again,” Shamera Morales ‘11 stated. “I was a boys are the ones cheering. Last year the game “I am very excited for District Art Night freshman last year, and I felt like my first year was postponed to June, nearly seven months this year.” Brie Dace ’09 stated. “It’s a great wasn’t really complete with all of the activities later than its original date. -

Christmas Parade’

‘THE CHRISTMAS PARADE’ CAST BIOS ANNALYNNE McCORD (Hailee Anderson) – AnnaLynne McCord is an actress, writer and director. Known as an actress for playing vixen-type roles, McCord first gained prominence in 2007 as the scheming Eden Lord on the FX television series “Nip/Tuck.” In 2008, she was the second actress to be cast in the CW series “90210,” portraying antiheroine Naomi Clark. For the role, she was nominated for a Teen Choice Award and received the Hollywood Life Young Hollywood Superstar of Tomorrow Award in 2009. In 2010, she won a Breakthrough of the Year Award in the category of "Breakthrough Standout Performance.” AnnaLynne most recently was seen playing Heather McCabe in the third season of the TNT hit series “Dallas.” AnnaLynne just recently wrapped production as the lead in the thriller, “Photographs.” Apart from acting, McCord also passionately contributes her voice and support to charities in her free time. She has been labeled by the Look to the Stars organization as "one of the strongest young female philanthropists standing up in Hollywood and fighting for the charities she believes in." In 2009 Connecticut Congresswoman Rosa L. DeLauro awarded McCord with a Congressional Honor for her tireless efforts to fight slavery and end human-trafficking. McCord resides in Los Angeles, CA. ### JEFFERSON BROWN (Beck Thomas) – Born in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Jefferson Brown moved with his family at age seven to Newmarket, Ontario. Returning to New Brunswick for his post-secondary education, he pursued a degree in Visual Art at Mount Allison University in Sackville. In his third year of university, Brown was cast in the school’s annual musical and fell in love with performing. -

She's Back EXCLUSIVE Jennie Garth Returns to Beverly Hills

www.resident.com • August 12-25, 2008 • Vol. 20, N0. 53 • $2.95 She's Back EXCLUSIVE Jennie Garth Returns to Beverly Hills PLUS Gossip Girl’s Matthew Settle Dishes the Dirt on the Show’s Second Season FALL ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE Music, Art, Theater and More: Event Picks from Famous New Yorkers COVER She’s back! Jennie Garth returns to the small screen on the new 90210 and reprises the role that turned her into a televi- sion icon. By Rachel Bowie elly Taylor has been through a lot. teen drama 90210, a spin-off of Aaron Spell- Resident: 90210 has to be one of tele- During her time at West Beverly, the ing’s original series. Although her character is vision’s favorite zip codes. Did you fictional high school she attended the same, this time, Garth roams the halls of ever imagine that the day would come on the television series Beverly Hills, West Beverly with a different purpose, play- where you would get to reprise your 90210, she saved her mother from a ing a guidance counselor and helping her role as Kelly Taylor? Kcocaine addiction, slept with her best friend’s students through the challenges they will un- Jennie Garth: I never thought that the boyfriend and overdosed on diet pills, all be- doubtedly face growing up in L.A.’s wealthi- show would come back from the dead. For fore graduation! But with age comes wisdom est zip code. As gossip swirls around which me, it was tucked away nice and neat and and Kelly is all grown up now. -

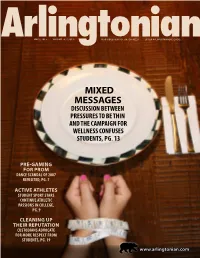

Mixed Messages Discussion Between Pressures to Be Thin and the Campaign for Wellness Confuses Students, Pg

may 3, 2013 Volume 76, Issue 8 1650 RIdgeview Rd., UA, oH 43221 uppeR ArlIngton HIgH scHool Mixed Messages diScussion between pressureS to be thin and the campaign for wellness confuSeS StudentS, pg. 13 Pre-gaMing for ProM dance Scandal of 2007 StudentS find their reviSited, pg. 7 handS are tied when it comeS to deciding active athletes Student Sport StarS whether to focuS continue athletic on nutrition or passionS in college, pg. 9 weight loss, pg. 13 cleaning uP their rePutation cuStodianS advocate for more reSpect from StudentS, pg. 19 www.arlingtonian.com advertisements Hair. For her, it means normal. It means no more stares. It means feeling beautiful Chocolates to live by.™ again. It means being a kid again. Donate your long locks of hair to a child struggling with cancer and other debilitating diseases. Artemis Medical Spa and Salon is helping Hawks Locks for Kids (founded by OSU athlete A.J Hawk and his wife, Laura) by holding a Cut-a-Thon on March 23rd from 10 am – 5 pm. You can make a difference and Artemis will give you a fantastic new hair style in return. Hair needs to be at least 12-14 inches in length to send and Graduation! cannot be chemically treated. For info call the Artemis at Celebrate with chocolate. 614-793-8346 and ask for Cheryl for more details! 3219 Tremont Road Upper Arlington, Ohio 43221 ARTEMIS (614) 326-3500 ONE LIFE • ONE BODY • ONE IMAGE [email protected] www.schakolad.com/store23 GET 10% OFF WITH YOUR STUDENT ID ALL YEAR! 2 MAY 3, 2013 visit us on our website at www.arlingtonian.com. -

Gossip Girl, 90210 Y One Tree Hill (The CW) Freaks and Geeks (NBC) Universidad De Sevilla, Facultad De Comunicación

Máster en Guión, Narrativa y Creatividad Audiovisual Universidad de Sevilla El género teen y la identificación de los adolescentes Autora: Pilar Baena. Directora: María del Mar Ramírez Diciembre de 2012 Foto de portada: Juan Luis Rincón Chamorro. Derechos de imagen: The Breakfast Club (Universal Studios) Gossip Girl, 90210 y One Tree Hill (The CW) Freaks and Geeks (NBC) Universidad de Sevilla, Facultad de Comunicación. MÁSTER UNIVERSITARIO EN GUIÓN, NARRATIVA Y CREATIVIDAD AUDIOVISUAL TRABAJO FIN DE MÁSTER El género teen en televisión y la identificación de los adolescentes. Director: María del Mar Ramírez Alvarado. Autor: Pilar Baena Fernández 1 "Querido señor Bernard: Admitimos el hecho de tener que quedarnos castigados todo un sábado por habernos portado mal, pero pensamos que está usted loco al intentar forzarnos a escribir un ensayo explicándole quiénes creemos ser, porque usted simplemente nos ve como quiere vernos. En pocas palabras, la definición más conveniente sería que hemos sacado en limpio lo que hay en cada uno de nosotros: un cerebro, un atleta, una irresponsable, una princesa y un criminal. ¿Contesta eso a su pregunta? Atentamente le saluda, El club de los cinco." (The Breakfast Club, John Hughes 1985) 2 Índice Introducción 4 1. Objetivos e hipótesis 6 2. Marco Teórico 7 3.1 Contextualización 7 3.1.1. Introducción al género teen 14 3.1.2 Características del género teen 16 3.2 ¿Quién es el adolescente? 32 3.2.1 Perfiles de adolescentes 33 3.2.1.1. La Princesa 33 3.2.1.2. El Atleta. 34 3.2.1.3. El Cerebrito 36 3.2.1.4. -

Numb3rs (Theme)

Delaware Winter Invitational, 2010 Numb3rs packet by Nick Lacock and Mark Pellegrini Tossups 1) Warning: year and team required. Throughout the season, this team wore a decal with the number 91 in memory of defensive end Marquise Hill. This team's quarterback openly admitted that they were trying to "kill" and "blow out" their opponents. In December, Mercury Morris went onto Sportscenter to perform a "diss" rap aimed at this team. In September, the Jets accused them of videotaping defensive signals, touching off the Spygate scandal. Wes Welker had 1,175 yards receiving while Randy Moss caught 23 of Tom Brady's 50 touchdown passes. For ten points, name the only NFL team to ever finish a regular season 16-0. ANSWER: 2007 New England Patriots 2) In this film, Whitey Duvall saves the protagonist from jail by convincing the judge to sentence him to community service coaching basketball, while Rob Schneider makes a minor appearance as the voice of a Mr. Chang, a waiter. The title of this movie comes from the fact that, throughout the course of this movie, several characters celebrate Hanukkah. Davey antagonizes fraternal twin midgets Whitey and Elanor in, for ten points, what animated film starring Adam Sandler? ANSWER: Eight Crazy Nights 3) The name's the same. David McCullough released a book by this name in 2005. That book revolves around the same events as an Avalon Hill wargame of this name, in which you can invade Canada. Sherman Edwards composed the music for the musical of this name, which was later turned into a film of the same name starring William Daniels and Howard Da Silva. -

Marieke-Oeffinger-Engl

Marieke Oeffinger Profession actor/actress, dubber, speaker, presenter Nationality German (Federal) State Bavaria 1st residence Munich Place of action Barcelona, Berlin, Cologne, Frankfurt a.M., Hamburg, Los Angeles, Munich, New York, Prague, Vienna Ethnic appearance White Central European/Caucasian Hair colour brown Hair length long Eye colour blue Stature slim Height 165 cm Confection size 34/36 Language(s) English - fluently French - basics Spanish - basics Dialects / accents Hessen Singing schlager - good musical - good chansons - basics Contact: Voice range soprano Musical instrument piano - basics Marieke Oeffinger Dancing jazz dance - concert level ballet - good showreel standard - basics German step - basics modern dance - basics (audio) dubbing hip-hop - basics (audio) commercial rock'n'roll - basics License B (car) TV host Special skills Produktpräsentationen, VIP Betreuung Area of operations Schauspiel, Moderation, Synchron, Hörspiel live, TV, Film References * Praktikum bei Columbia Tristar Home Entertainment, München * Produktion des Kurzfilms Die Katze und Heute macht man das wozu man Lust hat * Drehbuchseminar bei Brian Cordray (USA) * VIP Service und Betreuung bei der BAVARIA FILM GmbH * Produktpräsentation im Teleshopping * Mitwirken bei Fernsehreportagen * Hospitanz bei den Dreharbeiten zu dem Dokumentarfilm Ammas Ashram in Indien und Nepal im Frühjahr * Hospitanz bei den Dreharbeiten zu dem Dokumentarfilm Arena di Verona in Verona (Italien) im Sommer * Filmführungen über das Gelände der Bavaria Film Studios, Geiselgasteig -

PLUS Youth Impact Report ’09 Fia R D Y , D Ecember 4 , 2 0 0 9 V a R Iety

PLUS YOUTH IMPACT REPORt ’09 FIA R D Y , D ECEMBER 4 , 2 0 0 9 V A R IETY . C O M / F E A T U R ES n A 1 INSIDE THE ON-SET OF CHILDHOOD wo “Twilight” films have opened since T last year’s Youth Impact Report, demon- strating once again how talent not yet old enough GROWING UP to drink are driving some of the industry’s top properties. From teeny- bopper sensation Justin Bieber to YouTube break- Sam Emerson out Lucas Cruikshank SOCIAL CLICK: Nearly (aka “Fred”), these tyros IN CHARACTER are calling the shots. 2 million online fans were following Miley Cyrus when Top properties demand decade-or-more commitments from moppets — Peter Debruge, the teen celeb canceled her Associate Editor, Features Twitter account last October. By KATHY TRACY TW I EET S XTEEN rom “The Chronicles of Narnia” to “Twilight” and “Hannah Montana” to “Drake & Josh,” youth entertain- ment seems to depend less on one- T ech-savvy offs than massive multiyear proper- Fties. That in turn can put an enormous burden on the cast, who must commit the better part stars brave of their childhoods to playing characters indel- Power of Youth ibly identified with the franchise brand. In Variety fetes five stars – some cases, they are the brand on whom the WHEN DANIEL MET HARRY: Radcliffe who’ve used their fame virtual space whole enterprise depends. (The Harry Potter and co-stars Rupert Grint and Emma Wat- to aid others – at its an- series was able to replace its Dumbledore after son have been playing kid wizards since 2000.