Livelihood Zones in West Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Batik in Java and Santiniketan

Universiteit Leiden Journey of Textile Designs: A Case Study of Batik in Java and Santiniketan Master Thesis, Asian Studies (60 EC) 2015-16 Name of student: Deboshree Banerjee Student Number: s1684337 Date: 1st September 2016 Supervisors: Prof. dr. N.K. Wickramasinghe-Samarasinghe Prof. dr. P.R. Kanungo Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures and Tables......................................................................................................... iv Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... v Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Textiles: A Medium of Cultural Studies ......................................................................... 1 1.2. Diffusion Theory ............................................................................................................. 3 1.3. Literature Review: Javanese and Santiniketan Batik ...................................................... 4 1.3.1. Javanese Batik .......................................................................................................... 5 1.3.2 Santiniketan Batik ..................................................................................................... 7 1.4. Proposed Hypothesis ...................................................................................................... -

Research Article

Available Online at http://www.journalajst.com ASIAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Asian Journal of Science and Technology ISSN: 0976-3376 Vol. 08, Issue, 10, pp.60 84-6089, October, 2017 RESEARCH ARTICLE KANTHA EMBROIDERY-A WOMAN-CENTRIC PATH TOWARDS EMPOWERMENT FOR ARTISANS IN WEST BENGAL 1Dr. Debaleena Debnath and 2Sreenanda Palit 1Assistant Professor, Folklore Dept., Kalyani University, Nadia, West Bengal 2Associate Professor and Centre Coordinator-Fashion Communication, National Institute of Fashion Technology, Kolkata, Ministry of Textiles, Govt. of India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: Niaz Zaman describes the needlecraft of Kantha as "women's art”. Traditionally the Kantha embroidery Received 04th July, 2017 of Bengal has been the forte of women, unlike Zardosi and Ari work which is predominated by men Received in revised form folk. The craft has a history of being a revered recycled product. A Kantha is considered to be layers of 21st August, 2017 old sarees or dhotis quilted together to form a blanket, used by the poor as a protection against cold. Accepted 06thSeptember, 2017 Later the ‘nakshi’ form of it was born in the household of undivided Bengal as a portrait of women’s th Published online 17 October, 2017 aspiration and dream. The paper discusses how Kantha has been dominated by women and has eventually helped to empower hundreds of them. The various factors that made it woman-centric have Key words: been explored through primary research conducted among 50 artisans from Nanoor, Birbhum District, Kantha, Needlecraft, Quilting, and Kadambagachi, Barashat District of West Bengal. The study presents a comparative study of both Women empowerment, the clusters. -

Rabindranath Tagore's Model of Rural Reconstruction: a Review

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT.– DEC. 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Rabindranath Tagore’s Model of Rural Reconstruction: A review Dr. Madhumita Chattopadhyay Assistant Professor in English, B.Ed. Department, Gobardanga Hindu College (affiliated to West Bengal State University), P.O. Khantura, Dist- 24 Parganas North, West Bengal, PIN – 743273. Received: July 07, 2018 Accepted: August 17, 2018 ABSTRACT Rabindranath Tagore’s unique venture on rural reconstruction at Silaidaha-Patisar and at Sriniketan was a pioneering work carried out by him with the motto of the wholesome development of the community life of village people through education, training, healthcare, sanitation, modern and scientific agricultural production, revival of traditional arts and crafts and organizing fairs and festivities in daily life. He believed that through self-help, self-initiation and self-reliance, village people will be able to help each other in their cooperative living and become able to prepare the ground work for building the nation as an independent country in the true sense. His model of rural reconstruction is the torch-bearer of so many projects in independent India. His principles associated with this programme are still relevant in the present day world, but is not out of criticism. The need is to make critical analysis and throw new lights on this esteemed model so that new programmes can be undertaken based on this to achieve ‘life in its completeness’ among rural population in India. Keywords: Rural reconstruction, cooperative effort, community development. Introduction Rathindranath Tagore once said, his father was “a poet who was an indefatigable man of action” and “his greatest poem is the life he has lived”. -

Call for Papers

'72 r , i ,/,,; f; VISVA-BHARAI'I (Founded by Rabindranath Tagore) A central university and Institution of National Impoftance -, International Conference "Rodd M4p--1tor the pevelopme?lof Rural rourisrn in & around Birbhum" NOVEMBER 08.10, 2OI9 Organised Bg Vis u a-Bhar ati, S antiniketan In Collaboration with To'urism Department, Gout. of West Bengal Call for Papers FOCAL THEME Tourism is likel1' to be a growing industry in India for some tirne. It has tremendous potential due to peoples' interest in travel and desire to explore nature and religious sites' Tourism in India is expected to play a key role in the country's economic growth, human resource, culture, wealth of the country in terms of foreign exchange earnings, etc. Simultaneously, it has a direct bearing on local culture, socio-economic patterns of life, traditions, lbod habits, language, values and ethics of the local people due to irequent visits of national and international tourists to attractive tourist destinations, R-ural tourism is essentially an activity which takes place in the countrysicle. The rural totirisrm is cr:rrently the trend of the world and also got recognition as an important .i.st':'lment of grorvth ofthe rural communitie s. It is defined as - any form of tourism that ''i''\\'cases rural life, art, culture and heritage at rural locations, t.hereby contribgiing tc the development of th,e local community economically and socially as well as enabling interaction betwr:en tcurists and locals for a more enriching tourism experience. Birbhum is regarded as the 'Land of Red Soil'. Birbhum has a culture of its own and is immersed in the richness of the cultural heritage of India in general and West Bengal in parti,:ular. -

Vibhash C Jha.Cdr

NGJI, An International Peer-Reviewed Journal NGSI-BHU, ISSN: 0027-9374/2020/1733 Vol. 66, No. 2, June 2020 Environmental Risk Assessment: A Geomorphic Investigation over the Bolpur-Santiniketan-Illambazar Lateritic Patch of Birbhum District, West Bengal, India Vibhash C. Jha1 and Subhasis Ghosh2 1Professor of Geography, Former Vice-Chancellor, TMBU, Former Director NATMO, DST, Government of India, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, 2Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, (Corresponding author's e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract A proper geomorphic study of a region can be useful in understanding past and present environmental circumstances and analyzing potential environmental risks. Careful analysis of morphodynamic processes and existing diagnostic landforms reveal several aspects about the origin, characteristics and possible pattern of morpho-climatic interactions on the landscape over temporal scale, which helps significantly in proper terrain evaluation from societal welfare and integrated management point of view, including environmental risk assessment and disaster management. This paper has made a thorough geomorphic investigation based on intensive fieldwork and multi-sourced remote sensing data to characterize the lateritic soil profile and landforms of the study area in respect to their morphology and Physico-chemical properties at the different sites of land degradation to understand the outcome of morphoclimatic interactions on the landscape over time, and to evaluate the severity of operation with pedo-geomorphic constraints in the lateritic environment for sustainable management purposes. It is found that the region is highly sensitive to weathering, mass movement and denudational activities, mainly caused by rainwater erosion which has resulted into varied landforms including well-developed rills and gullies, lateritic ridges, isolated residual hills etc and generated a unique identity to this part of the lateritic region. -

1 PERSONAL PROFILE Name : Pran Kumar

1 PERSONAL PROFILE Name : Pran Kumar Rajak Designation : Assistant Professor Department : Philosophy Academic Qualification : M.A. in Philosophy, B. T. Office address : MUC Women’s College, Burdwan (W. B.) Phone (Office) : 03422533168 Phone/Mobile : 9474321505 Correspondence Address : Vill + P. O. - Panchthupi Dist - Murshidabad PIN – 742161 (W.B.) E-mail : [email protected] Personal Profile including : a) Biography: Mr Pran Kumar Rajak graduated from Kandi Raj College, Murshidabad and did his M.A. from Visva- Bharati, Santiniketan, West Bengal. He has been teaching at MUC Women’s College, Burdwan since 2010. Formerly, he taught at Patikabari H. S. School, Murshidabad for more than eleven years. He acted as Joint- Coordinator in UGC Sponsored National Seminar on “The Place of Vedanta in Contemporary Indian Philosophy”, 14 September, 2011 and also on “Swami Vivekananda and the Present Day Indian Society”, 12-13 September, 2013. His areas of interest are Indian Philosophy and Contemporary Indian Philosophy. He has contributed scholarly articles to various journals and magazines. b) Research activity (if any) in bullet form (or within 250 words) Past Research program: Nil Present Research program: Nil Future research plan: Indian Philosophy c) List of Publication (if required add Annexure) Published Articles: 1. “Vhishmer Icchāmrityu Hala Aicchik Swastimrityu”, BARNOLIPI: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol.I. Issue VI. Apr., 2012. (ISSN 2249-2666) Pp. 107-113. 2. “Dalit O Ādibāsi, Ucchabarner Dwāra Ājo Padadalita”. BARNOLIPI: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol.II. Issue I. June, 2012. (ISSN 2249-2666) Pp. 136-148. 2 3. “Rupabaishamya - Kālo Meyer Kopāl Manda”, PURVA BHARAT (Mānush O Sanskriti). [Pub.by East Indian Society for the Studies of Social Sciences] Vol. -

Flyer BSW SMC Webinar

Sonamukhi College (NAAC Accredited B) The Department of Social Work In collaboration with Amar Kutir Society for Rural Development Hosting a National Webinar On “Social Work as a Career in India: Scope and Opportunities” Date: 5th July, 2021 Time: 11a.m.-1.30 p.m. No Registration Fees E-certificates will be provided to registered participants For Registration Click Here: https://forms.gle/cGkAdQBjG34Ev1ZY6 YouTube LIVE Streaming Link: https://youtu.be/3AKUHaYQv3k About the College and BSW Department Sonamukhi College, Sonamukhi, Bankura, West Bengal (presently affiliated to Bankura University) an institute of higher education was established in the year 1966 to fulfil the dreams of a few noble souls of the times. The contribution and role of the college as a pioneering in spreading education in the area cannot be overlooked. However, the department of social work is newly introduced subject in this college. It has started its journey in Sonamukhi College in the year 2019. This is the first college under the Bankura University who has initiated to introduce this course in undergraduate level. The department offers honours in Social Work (BSW). About the Course Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) is a three-year undergraduate degree that offers knowledge and skills to aspirants to prepare them for a professional career in social welfare. Graduates with a degree in social work have numerous employment opportunities in various sectors such as community development, education, industry, correctional and juvenile homes, rehabilitation centres, health care services, women, children, differently abled persons, social defence, poverty groups etc. Thus, the course is ideal for the students who wish to bring change in society by extending hands to the marginalized and unprivileged section of the society. -

Baisakhi Datta

BAISAKHI DATTA NATIONALITY: INDIAN. CATEGORY: GENERAL. Address : 46 Netaji Colony, Baranagar, Kolkata – 700090 Date of Birth: 20.10.1982 Designation: Govt. Approved College Teacher Dept. of Geography Women's College, Calcutta University of Calcutta Email: [email protected] Contact No. 9830200048. Educational Qualification: Course Subject Institution Year Percentage Class Madhyamik Maths, Bengali, Baranagar Mohan 1998 77.37% I English, Physical Sc, Girls High School Division Life Sc, History, *Above 80% Marks in Geography, Work Maths, Physical Sc, Life Sc Education Higher Bengali, english, Baranagar 2000 63.5% I Secondary Economics, Rajkumari Balika Division Geography, Maths, Vidyalaya *Above 80% Marks in Political Sc Geography B.Sc. Geography (Honours) University of 2003 64.75% I Class Calcutta M. Sc Geography University of 2005 63.5% I Class Calcutta PGDIP RS & GIS Jadavpur University 2008- ---- --- 09 Advance Course Geoinformatics Jadavpur University 2010- ---- ---- in 11 Geopinformatics Specialization: B.Sc Cartography, M.Sc. Cartography Software Knowledge: MapInfo, Erdaas, Arc GIS, QGIS etc. Academic Achievement: National Scholarship , Govt. of India Teaching Experience: 14 Years in UG level in Degree colleges. Contractual Whole Time Lecturer of Mrinalini Datta College Birati (North 24 Pgs.) in 2006 Contractual Whole Time Lecturer of Dinobandhu Mahavidyalaya Bongaon(North 24 Pgs.). Worked as Departmental In-Charge, 17th Aug 2006 to 18th Sept 2007. Contractual Whole Time Lecturer of Women”s College Calcutta from Sept 2007 Govt. Approved Whole Time Teacher of Womens College, Calcutta from 2010 to till date Attached with M.A/M.Sc PG courses offered by Vidyasagar University DDE, Centre WCC experienced as Subject co-coordinator Geography M.A/M.Sc course, Vidyasagar University DDE, Centre WCC for the session 2009-2012 Teaching & Research Interest Cartography, Social Geography, Cultural Geography, Population Geography, Environmental Geography, Statistical Methods in Geography, Human Geography, Rural Development, Sustainable Development. -

Sriniketan: a Model Centre for Rural Reconstruction

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 6 Issue 11||November. 2017 || PP.57-61 Sriniketan: A Model Centre for Rural Reconstruction Dr Mahua Das, Prof. Dept.of Political Science, Women’s College, Calcutta, and Principal, Women’s College, Calcutta Corresponding Author: Dr Mahua Das --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 23-10-2017 Date of acceptance: 09-11-2017 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION The emergence of Sriniketan as a Rural Reconstruction Centre Over a century ago, Rabindranath Tagore, as a reaction to the colonial system of education, felt the need for a non-conventional and an integral system of education. To give shape to his ideas, he founded Visva- Bharati and its two centres – Santiniketan and Sriniketan, each having different programmes and objectives. The Institute of Rural Reconstruction was founded in 1922 at Surul at a distance of about three kilometres from Santiniketan. It was formally inaugurated on February 6, 1922 with Leonard Elmhirst as its first Director. Thus the second but contiguous campus of Visva-Bharati came to be located at a site which assumed the name of Sriniketan. The chief object was to help villagers and people to solve their own problems instead of a solution being imposed on them from outside. Sriniketan focused on agriculture and rural development with the co-operative efforts of the villagers themselves and its aim was to develop a better life for the people of rural India by educating them to be self-reliant and encouraging the revival of village arts and crafts. -

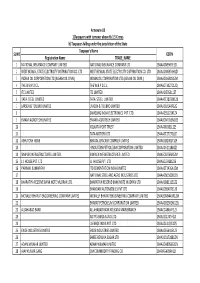

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Annual Report 2015-2016

VISVA-BHARATI Annual Report 2015-2016 Santiniketan 2016 YATRA VISVAM BHAVATYEKANIDAM (Where the World makes its home in a single nest) “ Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India's obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India's right to accept from others their best ” -Rabindranath Tagore Contents Chapter I ................................................................i-v Department of Biotechnology...............................147 From Bharmacharyashrama to Visva-Bharati...............i Centre for Mathematics Education........................152 Institutional Structure Today.....................................ii Intergrated Science Education & Research Centre.153 Socially Relevant Research and Other Activities .....iii Finance ................................................................... v Kala Bhavana.................................................157 -175 Administrative Staff Composition ............................vi Department of Design............................................159 University At a Glance................................................vi Department of Sculpture..........................................162 Student Composition ................................................vi Department of Painting..........................................165 Teaching Staff Composition.....................................vi Department of Graphic Art....................................170 Department of History of Art..................................172 -

Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State City PIN Details Amount Transfer to IEPF DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O

Biocon Limited Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend for the FY 2007-08 Folio NO/Demat Due date for Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State City PIN details Amount transfer to IEPF DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 250.00 22-AUG-2015 CAP MARK SERV PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 250.00 22-AUG-2015 CAPITAL MKT SER C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 250.00 22-AUG-2015 HEAD CAP MARK SERV CPU PL 82/83 RD 7 ST 15 OPP SPECAILITY RANBAXY LAB MIDC ANDHERI EAST MUMBAI URMILA LAXMAN SAWANT C/O KOTAK MAHINDRA BANK LTD VINAYA INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400098 BIO043838 250.00 22-AUG-2015 BHAVYA COMPLEX 5TH FLR 159-A CST ROAD KALINA SANTACRUZ E MUMBAI PHONE- 56768300 NEHA KAMLESH SHAH G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MARKET INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043408 250.00 22-AUG-2015 SERVISES CENTRAL PROCESSING UNIT PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 5 MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI NO NA INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI BIO054733 250.00 22-AUG-2015 NO NA INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI BIO054734 250.00 22-AUG-2015 NO NA INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI BIO054748 250.00 22-AUG-2015 NO 305 GOLF MANOR WIND TUNNEL ROAD 22-AUG-2015 MANISH SALNI MURUGESHPALYA BANGALORE INDIA KARNATAKA BANGALORE 560017 BIO038066 250.00 G 16 Marina Arcade Connaught Circus New Madhubani Investments P Ltd Delhi INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110001 IN30177410005267 4250.00 22-AUG-2015 VANDANA GOGIA HOUSE NO.904 SECTOR-28 FARIDABAD INDIA HARYANA FARIDABAD 121002 IN30209210046456 2500.00 22-AUG-2015 C/O JITENDRA PRATAP SINGH RESIDENT ENGINEER TEMPORARY DEPART.