GREGORY Drone Geographies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

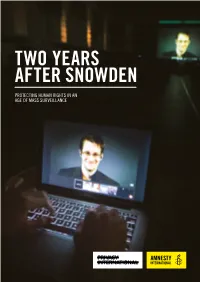

Two Years After Snowden

TWO YEARS AFTER SNOWDEN PROTECTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN AN AGE OF MASS SURVEILLANCE (COVER IMAGE) A student works on a computer that is projecting former U.S. National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden as he appears live via video during a world affairs conference in Toronto © REUTERS/Mark Blinch 2 TWO YEARS AFTER SNOWDEN JUNE 2015 © REUTERS/Zoran Milich © REUTERS/Zoran “The hard truth is that the use of mass surveillance technology effectively does away with the right to privacy of communications on the Internet altogether.” Ben Emmerson QC, UN Special Rapporteur on counter-terrorism and human rights EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On 5 June 2013, a British newspaper, The exposed by the media based on files leaked by Guardian, published the first in a series Edward Snowden have included evidence that: of revelations about indiscriminate mass surveillance by the USA’s National Security Companies – including Facebook, Google Agency (NSA) and the UK’s Government and Microsoft – were forced to handover Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). their customers’ data under secret orders Edward Snowden, a whistleblower who had through the NSA’s Prism programme; worked with the NSA, provided concrete evidence of global communications the NSA recorded, stored and analysed surveillance programmes that monitor the metadata related to every single telephone internet and phone activity of hundreds call and text message transmitted in of millions of people across the world. Mexico, Kenya, and the Philippines; Governments can have legitimate reasons GCHQ and the NSA have co- for using communications surveillance, for opted some of the world’s largest example to combat crime or protect national telecommunications companies to tap security. -

+ – . Evidentiary Realism Exhibition Presented by NOME Gallery +

. Evidentiary Realism exhibition presented by NOME Gallery + Fridman Gallery in NYC. February 28 – March 31, 2017 287 Spring St, New York, NY 10013. Artists talk moderated by Hrag Vartanian and opening 5-9pm on Feb. 28th More information on the website EvidentiaryRealism.net Artists: Nora Al-Badri & Jan Nikolai Nelles, Amy Balkin, Josh Begley, James Bridle, Ingrid Burrington, Harun Farocki, Hans Haacke, Thomas Keenan & Eyal Weizman, Navine G. Khan-Dossos, Mark Lombardi, Kirsten Stolle, Suzanne Treister. Curated and organized by Paolo Cirio. Evidentiary Realism features artists engaged in investigative, forensic, and documentary art. The exhibition aims to articulate a particular form of realism in art that portrays and reveals evidence from complex social systems. The truth-seeking artworks featured explore the notion of evidence and its modes of representation. Evidentiary Realism reflects on post-9/11 geopolitics, increasing economic inequalities, the erosion of civil rights, and environmental disasters. It builds on the renewed appreciation of the exposure of truth in the context of the cases of WikiLeaks, Edward Snowden, the Panama Papers, and the recent efforts to contend with the post-factual era. Contemporary sharing and processing of information in an open global collaborative environment entails an amplified sense of reality. Leaks, discoveries, and facts are collectively verified and disseminated among numerous distribution networks. Techniques of presentation and engaging the public have been evolving in the same direction—through reconfiguration of media and languages, the evidence is presented in a variety of strategies and artifacts in dialogue with contemporary art practices. Evidentiary Realism focuses on artworks that prioritize formal aspects of visual language and mediums; diverging from journalism and reportage, they strive to provoke visual pleasure and emotional responses. -

Drone Geographies Derek Gregory

Drone geographies Derek Gregory Last year Apple rejected Josh Begley’s Drones+ app Homeland insecurities three times. The app promised to send push noti- The first set of geographies is located within the fications to users each time a US drone strike was United States, where the US Air Force describes reported, but Apple decided that many people would its remote operations as ‘projecting power without find it ‘objectionable’ (they said nothing about what vulnerability’. Its Predators and Reapers are based they might feel about the strikes). When he defended in or close to the conflict zone, where Launch and his thesis at NYU earlier this year, Begley asked: ‘Do Recovery crews are stationed to handle take-off and we really want to be as connected to our foreign landing via a C-band line-of-sight data link; given the policy as we are to our smart phones? … Do we really technical problems that dog what Jordan Crandall want these things to be the site of how we experience calls ‘the wayward drone’, there are also large mainte- remote war?’1 These are good questions, and Apple’s nance crews in-theatre to service the aircraft.3 Once answer was clear enough. A number of other artists airborne, however, control is usually handed to flight have also used digital platforms to bring into view crews stationed in the continental United States via a these sites of remote violence – I am thinking in Ku-band satellite link to a ground station at Ramstein particular of Begley’s Dronestream and James Bridle’s Air Base in Germany and a fibre-optic cable across the Dronestagram, but there are a host of others2 – and Atlantic. -

Security Without Iot Mandatory Backdoors Carl Hewitt

Security without IoT Mandatory Backdoors Carl Hewitt To cite this version: Carl Hewitt. Security without IoT Mandatory Backdoors: Using Distributed Encrypted Public Recording to Catch & Prosecure Criminals. 2016. hal-01152495v12 HAL Id: hal-01152495 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01152495v12 Preprint submitted on 29 Feb 2016 (v12), last revised 14 Jun 2016 (v14) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Security without IoT Mandatory Backdoors Using Distributed Encrypted Public Recording to Catch & Prosecute Criminals Our greatest enemy is our own apathy. Bill Mullinax Carl Hewitt Board Chair of Standard IoTTM Foundation https://plus.google.com/+CarlHewitt-StandardIoT/ The Internet of Things (IoTi) is becoming pervasive in all aspects of life including personal, corporate, government, and social. Adopting IoT mandatory backdoorsii ultimately means that security agencies of each country surveil IoT in their own country and perhaps swap surveillance information with other countries.[11][30]][32] Security agencies have proposed -

Drone Lyrics US Terrorism and Digital Biopower

Drone Lyrics US Terrorism and Digital Biopower Erin A. Corbett Drone Lyrics 2014-2015 Committee Chair: Stephen Dillon Committee Member: Lorne Falk © Copyright Erin Corbett, 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family and friends for all of their support and excitement. Even though you still have to write down the title of my self-designed major in order to remember it, I thank you for that extra effort. Many thanks to my committee, Stephen Dillon and Lorne Falk for believing in my project and taking me on as an advisee. Your guidance and the time you have offered me throughout this project have helped me create this work, and I cannot imagine what it would look like without all of your support. Thank you to each professor at Hampshire College who has helped mold my critical lens and my studies over the past four years. You have impacted my studies, my interests, and most importantly my mind. For you— Contents Introduction: Digital Disposability and the Global War on Terror 1 VULNERABILITY The Drone, the Apparatus, the Human 14 Drone Imagery in the Digital Era 18 Marriage Industrial 22 IMAGINED IDENTITIES Invisible 28 Charlie Hebdo: The Case for Satire or Racism? 32 Free Speech to Terror Threat 36 Terror of “Illegality” 41 SPECTACLES Transportation Security 46 Intentional Language 51 Veterans Day and American Exceptionalism 55 BEYOND THE FRAME On Framing the Other 62 First Worldism 67 “They had lives beyond the violence by which they are known” 71 EROTICISM On the NSA, Privacy, and the Home 76 Blaming the Victim 80 On Nicknaming Predators 86 THE BODY The Case for Reproductive Justice 91 Jane Doe 95 Whiteness and Police Violence in the Land of the Free 101 Conclusion: An Era of Digital Biopower 106 Bibliography 115 0 Introduction Digital Disposability and the Global War on Terror Anwar al-Awlaki, a Yemeni-American male, was killed by a US drone in Yemen on September 30, 2011. -

Lethal Surveillance: Drones and the Geo-History of Modern War A

Lethal Surveillance: Drones and the Geo-History of Modern War A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Katharine Hall Kindervater IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Eric S. Sheppard May 2015 © 2015 by Katharine Hall Kindervater Acknowledgements I first would like to thank my advisor, Eric Sheppard. Through long discussions, patient readings, and encouraging feedback, Eric has not only supported this project in its many twists and turns, but has also served as a mentor in the truest sense. I have learned a lot about how I now want to shape and foster my interactions with future students and advisees, using him as a model. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee as a whole, which includes Eric, Vinay Gidwani, Bruce Braun, Cesare Casarino, and JB Shank. Over the many years of graduate school, my conversations with each of you have formed the basis of the arguments in the thesis. I only manage to scratch the surface here, but it sets the groundwork for what I hope are life-long investigations into questions of modern science, violence, and state power. More importantly, as I reflect on why I have assembled such a formidable committee, I am reminded that you all have taught me how to read. My own encounter with philosophy and theory has been the greatest and most unexpected gift of my decision to start graduate school and has changed the direction of my life in many ways. I treasure that and my time spent with each of you. -

Drone Technopolitics: a History of Race and Intrusion on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1948-2016

Drone Technopolitics: A History of Race and Intrusion on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1948-2016 by Iván Chaar-López A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Lisa Nakamura, Co-Chair Professor Alexandra Minna Stern, Co-Chair Associate Professor John Cheney-Lippold Professor Paul N. Edwards Iván Chaar-López [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-4731-6013 © Iván Chaar-López 2018 DEDICATION To Yiyi and all those who steadfastly struggle to build a different kind of world. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The pages that follow would never have been possible without the contributions and support of many people. They were present during those moments of potential, excitement, and difficulty in the research and writing process. And for all their time, thoughtfulness, work and kindness I will forever be grateful. Research for this dissertation relied on the support of various people and organizations. Archivists and librarians at the Library of Congress, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services History Library, the San Diego Air & Space Museum, and the Seattle Public Library shared their breadth of knowledge about their research materials. They also suggested new and unexpected avenues of inquiry. Catherine Morse and Alexa Pearce at the University of Michigan Library were instrumental in identifying primary source sites to explore for the project. Funding support was obtained from the Rackham Graduate School and the Department of American Culture at the University of Michigan, the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress, and from my mentor and dissertation co-chair, Lisa Nakamura. -

Struggling to Reduce the Damage

SportingGreen SanFrancisco Chronicle and SFChronicle.com | Sunday, October 28, 2018 | Section B xxxxx• THE FUTURE OF FOOTBALL Carlos Avila Gonzalez / The Chronicle The 49ers exit the locker room on their way to the field before a preseason game against the Dallas Cowboys at Levi’s Stadium on Aug. 9. By Eric Branch The series In February, Josh Begley, a For years, mount- STRUGGLING San Francisco native and Cal ing evidence has graduate, finished producing linked football one of the most haunting violence with brain short films of 2018. trauma and life- For more than five minutes, threatening condi- TO REDUCE viewers are presented with tions. Now that we know the sport can stitched-together footage that produce deadly includes stretchers, motion- results, where do less bodies, thousand-yard we go from here? stares and high-impact colli- THE DAMAGE sions that result in flying Today: How is the spittle and, on one occasion, a NFL trying to make pair of trembling, locked arms its game safer? B1 As a violent sport wrestles with effects on brains, that suggest a seizure. We know what Begley’s film, “Concussion needs to be done. how is the NFL making things safer for players? Protocol,” is a compilation of But will we finally every reported concussion do it? A1 from the 2017 NFL season. An avid football fan who Monday: Falling increasingly struggles with youth participation the game’s violence, Begley is a sign of things wanted to create a historical to come. record of the carnage to The NFL reported 291 concussions which many fans have be- Tuesday: What 291 during the 2017 season, a16.4 percent come desensitized. -

Making Drones Illegal Based on a Wrong Example: the U.S. Dronified Warfare

TURKISH JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES Türkiye Ortadoğu Çalışmaları Dergisi Vol: 3, No: 1, 2016, ss.39-74 Making Drones Illegal Based on a Wrong Example: The U.S. Dronified Warfare Gloria Shkurti* Abstract A concoction between the technology, entertainment and military has resulted in a ‘new’ kind of warfare, which has started to determine the American coun- terterrorism strategy, the dronified warfare. The U.S. for a long time now has been the leader in the production and usage of armed drones and has attracted a lot of criticism regarding the way how it conducts the drone strikes, which in many cases has resulted in civilians killed. The U.S. dronified warfare has become the main determinant when discussing the legality, morality and ef- fectiveness of the drone as the weapon, as many critics fail in distinguishing drone as a weapon and dronified warfare as a process. This paper argues that if analyzed separately from the U.S. example, drone is a legal and moral weap- on. Nevertheless, the paper emphasizes the fact that the U.S. must change its current way of conducting the strikes by being aware of the fact that the irre- sponsible way it is acting in the Middle East and regions around, sooner or later will backfire. Keywords: Dronified Warfare, U.S., Legality, Morality, Effectiveness *Assistant to Editor-in-Chief of Insight Turkey, SETA, [email protected] 39 TÜRKİYE ORTADOĞU ÇALIŞMALARI DERGİSİ Turkish Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Cilt: 3, Sayı: 1, 2016 , ss.39-74 Dronların İllegalleştirilmesine Yanlış Bir Örnek Olarak ABD’nin Dronlaştırılmış Savaşı Gloria Shkurti* Özet Dronlaştırılmış savaş (dronified warfare), ABD’nin Terörle Mücadele Strate- jisinde teknolojinin, eğlencenin ve ordunun bir karışımından oluşan yeni bir savaş türü olarak görülmeye başladı. -

Security Without Iot Mandatory Backdoors Carl Hewitt

Security without IoT Mandatory Backdoors Carl Hewitt To cite this version: Carl Hewitt. Security without IoT Mandatory Backdoors: Using Distributed Encrypted Public Recording to Catch Criminals. 2015. hal-01152495v10 HAL Id: hal-01152495 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01152495v10 Preprint submitted on 29 Dec 2015 (v10), last revised 14 Jun 2016 (v14) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Security without IoT Mandatory Backdoors Using Distributed Encrypted Public Recording to Catch Criminals Our greatest enemy is our own apathy. Bill Mullinax Carl Hewitt Board Chair of Standard IoTTM Foundation https://plus.google.com/+CarlHewitt-StandardIoT/ The Internet of Things (IoT)i is becoming pervasive in all aspects of life including personal, corporate, government, and social. Adopting IoT mandatory backdoorsii ultimately means that security agencies of each country surveil IoT in their own country and perhaps swap surveillance information with other countries.[9][25][27] Security agencies have proposed that it must be possible -

Security Without Iot Mandatory Backdoors Carl Hewitt

Security without IoT Mandatory Backdoors Carl Hewitt To cite this version: Carl Hewitt. Security without IoT Mandatory Backdoors: Using Distributed Encrypted Public Recording to Catch & Prosecute Suspects. 2016. hal-01152495v13 HAL Id: hal-01152495 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01152495v13 Preprint submitted on 20 Apr 2016 (v13), last revised 14 Jun 2016 (v14) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Security without IoT Mandatory Backdoors Using Distributed Encrypted Public Recording to Catch & Prosecute Suspects Our greatest enemy is our own apathy. Bill Mullinax Carl Hewitt Board Chair of Standard IoTTM Foundation https://plus.google.com/+CarlHewitt-StandardIoT/ This article explains how Citizens' civil liberties can be preserved by banning Internet of Things (IoTi) mandatory backdoors while at the same time effectively catching and prosecuting suspects (such as alleged “terrorists”). IoT devices are becoming pervasive in all aspects of life including personal, corporate, government, and social. Adopting IoT mandatory backdoors -

An Organizational Case Study of a Reentry Organization Ifeoma Yvonne Ajunwa Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

Brokering Freedom: An Organizational Case Study of a Reentry Organization Ifeoma Yvonne Ajunwa Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Ifeoma Yvonne Ajunwa All rights reserved ABSTRACT Brokering Freedom: An Organizational Case Study of a Reentry Organization Ifeoma Yvonne Ajunwa This dissertation employs an organizational approach to examine how reentry organizations seek to provide social value as public-private partnerships with the mission statement of aiding the reintegration of the formerly incarcerated. With the help of a case study of a reentry organization in Cleveland, Ohio, I examine the sociological significance of the discursive “brokerage metaphor” of reentry organizations as brokers of the social and cultural capital the formerly incarcerated require as catalysts for their reintegration back into society. Based on ethnographic data and in-depth field interviews collected over a period of 16 months in Cleveland, Ohio, my research finds that the “brokerage metaphor” for reentry elides important factors which play an integral role in the organizational behavior of reentry organizations and the sociological experience of reentry for the formerly incarcerated. These other factors notably include the competitive and regulatory organizational environment of the reentry organization, and the intersectional identities of formerly incarcerated women. These external factors reveal the paradox of the public-