How the Labour Market Evaluates Italian Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prof. Caterina Rizzi

Caterina Rizzi PROF. CATERINA RIZZI Dipartimento di Ingegneria Gestionale, dell’Informazione e della Produzione Università di Bergamo, Viale G. Marconi, 5, Dalmine (BG) Italy email: [email protected] www.unibg.it/vk Laurea Degree in Physics received from the University of Milan in 1985. Since 1 Nov 2001 Full Professor of Technical Drawing and Product Life-cycle Management for Mechanical and Management Engineering at Faculty of Engineering, University of Bergamo, and Human Modelling (School of Medicine and Surgery). From Nov 1995 to Oct 2001 Associate Professor of Computer Aided Design, Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Parma. From Nov 1992 to Oct. 1995 Associate Professor of Technical Drawing, Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University Federico II of Naples. UNIVERSITY SERVICES - From September 2014, Head of the Department of Management, Information and Production Engineering. - From October 2015, Member of the Academic Senate of the University of Bergamo. - From September 2016 Member of Technology Transfer Board at University of Bergamo. - From February 2017 Member of the Management Board of the International Medical School, University of Bergamo, Università di Milano Bicocca and University of Surrey, UK. - From June 2017 Coordinator and Member of the academic board of the PhD programme in Technology, Innovation and Management (TIM) jointly founded University of Bergamo and University of Naples Federico II. - From 2012 to August 2014, Deputy Head of the Engineering Department, University of Bergamo. - From November 2005 to 2010 Research Delegate at University of Bergamo. - From May 2006 to October 2015 Chair of Patent and Technology Transfer Board at University of Bergamo. - From 2008 to 2012 Director of the COGES (Centre for Innovation and Knowledge Management) Centre, University of Bergamo. -

Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Typically Developing Peers: an Online Survey

brain sciences Article Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Typically Developing Peers: An Online Survey Annalisa Levante 1,2,* , Serena Petrocchi 2,3 , Federica Bianco 4 , Ilaria Castelli 4, Costanza Colombi 5,6, Roberto Keller 7, Antonio Narzisi 5 , Gabriele Masi 5 and Flavia Lecciso 1,2 1 Department of History, Society, and Human Studies, University of Salento, 73100 Lecce, Italy; fl[email protected] 2 Laboratory of Applied Psychology, Department of History, Society, and Human Studies, University of Salento, 73100 Lecce, Italy; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Università della Svizzera Italiana, Via Buffi 13, 6900 Lugano, Switzerland 4 Department of Human and Social Sciences, University of Bergamo, 23129 Bergamo, Italy; [email protected] (F.B.); [email protected] (I.C.) 5 IRCCS Stella Maris Foundation, 56018 Pisa, Italy; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (G.M.) 6 Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA 7 Adult Autism Center, Mental Health Department, Local Health Unit ASL Città di Torino, 10138 Turin, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Background: When COVID-19 was declared as a pandemic, many countries imposed Citation: Levante, A.; Petrocchi, S.; severe lockdowns that changed families’ routines and negatively impacted on parents’ and children’s Bianco, F.; Castelli, I.; Colombi, C.; mental health. Several studies on families with children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Keller, R.; Narzisi, A.; Masi, G.; revealed that lockdown increased the difficulties faced by individuals with ASD, as well as parental Lecciso, F. -

University of Bergamo -ITALY KEY DATA SHEET - Academic Year 2020/21

University of Bergamo -ITALY KEY DATA SHEET - Academic year 2020/21 Name of the University Università degli Studi di Bergamo / University of Bergamo Erasmus code I BERGAMO 01 Erasmus Charter for Higher Education N° ECHE n. 29286 Webpage www.unibg.it Homepage for Incoming Students Vice –Rector and Institutional Coordinator for International Programs Prof. Matteo Kalchschmidt University of Bergamo Postal Address of INTERNATIONAL OFFICE INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Via dei Caniana, 2 -24127 – Bergamo ITALY Webpage https://en.unibg.it/global/students-exchange/erasmus- Homepage for Incoming Students incoming-students STAFF MANAGER and International Coordinator INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Elena Gotti Contact Persons ERASMUS and EXCHANGE PROGRAMMES INCOMING STUDENT ADVISORS: email: [email protected] Milena Plebani /Anna Maria Di Marco Tel. +39 035 2052.428/293 BILATERAL AGREEMENTS : Milena Plebani Tel +39 035 2052 428 email: [email protected] ICM (K107) : Blerta Topalli Tel+39 035 2052.197 email: [email protected] OUTGOING STUDENTS ADVISORS: email: [email protected] Marco Donizetti Tel. +39 035 2052831 Seila Canova Tel. +39 035 2052833 Daniele Valsecchi Tel. +39 035 2052468 TS Mobility and ERASMUS TRAINEESHIP: Giovanna Della Cioppa Tel. +39 035 2052832 email: [email protected] -Department of Management, Economics and Quantitative ECTS Departmental Methods: Prof. Maria Francesca Sicilia –e-mail: Coordinators [email protected] -Department of Law: Prof. SILVIO TROILO - e-mail: [email protected] -Department of Letters, Philosophy and Communication Studies: Prof. FRANCA FRANCHI e-mail: [email protected] -Department of Human and Social Sciences: Prof. ILARIA CASTELLI e-mail: [email protected] -Department of Foreign Languages, Literatures and Cultures Prof. -

Elisabetta Listorti

ELISABETTA LISTORTI Via Parma 24/C, Torino, 10152, Italy | 0039 3398779760 | [email protected] Date - place of birth: November 21th, 1990 - Lanciano (Ch) – Italy WORK EXPERIENCE From 1st October Centre for Research on Health and Social Care Management, Bocconi University, 2019 Milan, Italy From 1st May 2018 to Epidemiology Unit ASL TO3 (S.C. A D.U. Servizio sovrazonale di epidemiologia), 30th September 2019 Grugliasco, Italy From 1st April 2019 to Scholarship for the Department of Clinical and Biological Sciences, University of Turin, 30th September 2019 Italy Competences Management of research projects: identification and development of potential areas acquired of research; literature review; data analysis; production, communication and presentation of research outputs; coordination of a research group EDUCATION From January 2019 Master in Epidemiology, University of Turin, Italy Courses of Cohort Studies, Case Control Studies, Clinical Trials, Systematic Reviews, Survival Analysis, Geo statistical methods November 2014 – Ph.D. cum laude in Management, Production and Design, Politecnico di Torino, October 2018 Italy PhD thesis “Hospital procedures concentration: how to combine quality and patient choice. A managerial use of the volume-outcome association” Research topic: Planning problems in health care systems. Development of operational research models for volume allocation; use of econometric models for patient choice; creation of managerial algorithms for integrated approaches October 2012- Engineering and Management (Postgraduate -

Masters Erasmus Mundus Coordonnés Par Ou Associant Un EESR Français

Les Masters conjoints « Erasmus Mundus » Masters conjoints « Erasmus Mundus » coordonnés par un établissement français ou associant au moins un établissement français Liste complète des Masters conjoints Erasmus Mundus : http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/erasmus_mundus/results_compendia/selected_projects_action_1_master_courses_en.php *Master n’offrant pas de bourses Erasmus Mundus *ACES - Joint Masters Degree in Aquaculture, Environment and Society (cursus en 2 ans) UK-University of the Highlands and Islands LBG FR- Université de Nantes GR- University of Crete http://www.sams.ac.uk/erasmus-master-aquaculture ADVANCES - MA Advanced Development in Social Work (cursus en 2 ans) UK-UNIVERSITY OF LINCOLN, United Kingdom DE-AALBORG UNIVERSITET - AALBORG UNIVERSITY FR-UNIVERSITÉ PARIS OUEST NANTERRE LA DÉFENSE PO-UNIWERSYTET WARSZAWSKI PT-UNIVERSIDADE TECNICA DE LISBOA www.socialworkadvances.org AMASE - Joint European Master Programme in Advanced Materials Science and Engineering (cursus en 2 ans) DE – Saarland University ES – Polytechnic University of Catalonia FR – Institut National Polytechnique de Lorraine SE – Lulea University of Technology http://www.amase-master.net ASC - Advanced Spectroscopy in Chemistry Master's Course FR – Université des Sciences et Technologies de Lille – Lille 1 DE - University Leipzig IT - Alma Mater Studiorum - University of Bologna PL - Jagiellonian University FI - University of Helsinki http://www.master-asc.org Août 2016 Page 1 ATOSIM - Atomic Scale Modelling of Physical, Chemical and Bio-molecular Systems (cursus -

1 University of Bergamo -ITALY KEY DATA SHEET

University of Bergamo -ITALY KEY DATA SHEET - Academic year 2019/2020 Name of the University Università degli Studi di Bergamo / University of Bergamo Erasmus code I BERGAMO 01 Erasmus Charter for Higher Education N° ECHE n. 29286 Webpage www.unibg.it Homepage for Incoming Students Vice –Rector and Institutional Coordinator for International Programs Prof. Matteo Kalchschmidt University of Bergamo Postal Address of INTERNATIONAL OFFICE INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Via dei Caniana, 2 -24127 – Bergamo ITALY Webpage https://en.unibg.it/global/students-exchange/erasmus-incoming- Homepage for Incoming Students students STAFF MANAGER and International Coordinator INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Elena Gotti Contact Persons Head of International Office: Paola Riva ERASMUS and EXCHANGE PROGRAMMES INCOMING STUDENT ADVISORS: email: [email protected] Milena Plebani e-mail: [email protected] Anna Maria Di Marco e-mail: [email protected] Tel. +39 035 2052293 BILATERAL AGREEMENTS :Rita Ferrari Tel +39 035 2052 428 email: [email protected] OUTGOING STUDENTS ADVISORS: email: [email protected] Marco Donizetti Tel. +39 035 2052831 [email protected] Seila Canova Tel. +39 035 2052833 [email protected] Daniele Valsecchi Tel. +39 035 2052468 [email protected] TS Mobility and ERASMUS TRAINEESHIP: Giovanna Della Cioppa Tel. +39 035 2052832 email: [email protected] -Department of Management, Economics and Quantitative ECTS Departmental Methods: Prof. Maria Francesca Sicilia –e-mail: Coordinators [email protected] -Department of Law: Prof. SILVIO TROILO - e-mail: [email protected] -Department of Letters, Philosophy and Communication Studies: Prof. FRANCA FRANCHI e-mail: [email protected] -Department of Human and Social Sciences: Prof. -

Università Degli Studi Di Bergamo

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI BERGAMO FACT SHEET-University of Bergamo a.y. 2016/17 Name of the Partner Institution University of Bergamo Erasmus code & ECHE code (if applicable) I BERGAMO01 / ECHE n. 29286 Country Italy Town and number of inhabitants Bergamo, about. 120.000 inhabitants Departments Management, Economics and Quantitative Methods; Foreign Languages, Literatures and Cultures, Human and Social Sciences; Letters, Philosophy and Communication Studies; Engineering; Law; Number of students at the University ca. 17.000 Website University/International Office www.unibg.it / www.unibg.it/relint Website for exchange incoming students : www.unibg.it/incoming Semester dates, including exam sessions 1st Semester: from September to February 2nd Semester: from February to July (depending on the Department) Preferred semester for receiving incoming No preference students Language of instruction Italian (recommended CEFR B1); some courses are taught in English (recommended CEFR B2): check www.unibg.it/subjects ECTS Yes Courses catalogue on internet – address www.unibg.it/ects Is there a possibility of taking courses from Yes different faculties/departments Housing arranged Yes Average accommodation cost per month € 300 Average cost of living per month excluding € 350 accommodation Website incoming students Accommodation www.unibg.it/accommodation Application Deadlines 1st Semester: June 15 th 2nd Semester: November 1 st Intensive Italian language courses for beginners Preparatory Italian language course before semester starts and non-intensive courses during the semester are offered free of charge. Each incoming student will also have access to PASE (Percorso Accoglienza Studenti Erasmus), an on-line Italian Language project that will familiarize students with the University of Bergamo and, at the same time, help them to develop and strengthen their Italian Language skills, even before their arrival in Bergamo. -

Università Degli Studi Di Bergamo

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI BERGAMO KEY DATA 2017/2018 Università degli Studi di Bergamo (University of Full Legal Name and Address of Bergamo) Institution Via Salvecchio, 19 I-24129 Bergamo - Italy Erasmus code /ECHE number (if I BERGAMO01 / ECHE n. 29286 applicable) Web-site www.unibg.it Name and Title of Head of Institution Prof. Remo Morzenti Pellegrini - Rector Erasmus+ Institutional and ECTS Co- Prof. Matteo Kalchschmidt – VICE RECTOR for ordinator INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Postal Address of INTERNATIONAL University of Bergamo OFFICE Via dei Caniana, 2 24127 – Bergamo ITALY Web-site International Office www.unibg.it/internazionalizzazione www.unibg.it/incoming www.unibg.it/outgoing HEAD OF INTERNATIONAL AND Elena Gotti email: [email protected] VOCATIONAL OFFICE Paola Riva e-mail: [email protected] INTERNATIONAL OFFICE (Teaching and staff mobility) COORDINATOR Tel. +39 035 2052830 www.unibg.it/relint MUNDUS STUDENTS AND ERASMUS Giovanna Della Cioppa: email: [email protected] TRAINEERSHIP Tel. +39 035 2052 832 BILATERAL AGREEMENTS Rita Ferrari email: [email protected] Tel. +039 2052428 INCOMING OFFICE INCOMING STUDENTS: Website: www.unibg.it/incoming Email: [email protected] Milena Plebani: email: [email protected] Anna Maria Di Marco: email: anna-maria.di- [email protected] Tel +39 035 2052293 24127 Bergamo, via S. Bernardino 72/E tel. 035 2052 830 / 831 / 832 / 833 fax 035 2052 838 e-mail: [email protected] Università degli Studi di Bergamo www.unibg.it Cod. Fiscale 80004350163 P.IVA 01612800167 1 UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI BERGAMO OUTGOING OFFICE OUTGOING STUDENTS: email: [email protected] website: www.unibg.it/outgoing Marco Donizetti [email protected] Daniele Valsecchi: [email protected] Seila Canova : [email protected] Tel. -

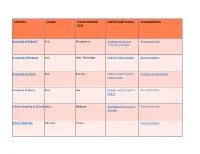

Accommodations English Taught Courses Primary Academic Field

University Country Primary Academic English Taught Courses Accommodations Field University of Padova* Italy Management Catalogues of course Accommodation units held in English University of Bergamo Italy Nano Technology English Taught Subjects Accommodation University of Venice Italy Business English Taught Degrees Housing and Residences and Curricula University of Siena Italy Law Degree courses taught in Accommodation English Latvian Academy of Culture Latvia Medicine Catalogue of the Courses Accommodation of Study Vilnius University Lithuania Physics Accommodation University of Bitola Macedonia Jewish Studies Tilburg University* Netherlands Law Bachelor's programs International Students Accommodation Master's programs Erasmus University* Netherlands Law Bachelors International Students Housing Masters Norwegian University of Norway Mathematics Taught in English Life and housing Sciences Gdansk University of Poland Nano Technology Study in English Accommodation Technology Adam Mickiewicz Poland Jewish Studies University Accommodation University Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski Poland Jewish Studies Accommodation University Poznan University of Poland Logistics Accommodation Technology Alexandru Ioan Cuza Romania Literature Degrees on offer in Accommodation University foreign languages University of Granada Spain Jewish Studies Accommodation University of Valencia Spain Nano Technology Courses Held in English Staying at Universitat de València University of Alcala Spain Humanities Accommodation in university residences University Country Primary -

FAQ INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS: Courses ,Enrollment, Residence Permit , Tax Code, Health

FAQ INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS: Courses ,Enrollment, residence permit , tax code, health insurance 1. WHICH ARE THE MASTER’S DEGREE PROGRAMS TAUGHT IN ENGLISH? The University of Bergamo offers two courses totally taught in English and five courses taught both in Italian and English. Here you can find a list of these courses. >Department of Management, Economics and Quantitative Methods: -Business Administration, Professional and Managerial Accounting (AAG) (Italian and English) -Economics and Data Analysis (English) -International Management, Entrepreneurship and Finance (English) >Department of School of Engineering: -Management Engineering Curriculum Business and Technology management (English) - Engineering and Management for Health (Italian and English) >Department of Foreign Languages, Literatures and Cultures - -Planning and Management of Tourism Systems (Italian and English) >Department of Human and Social Sciences -Clinical Psychology for Individuals, Families and Organizations (Italian and English) 2. WHAT IS THE DURATION OF A MASTER DEGREE COURSE? The duration of a Master Degree course is generally of two Academic years. 3. CAN I HAVE DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT MASTER DEGREE COURSES OFFERED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF BERGAMO? Yes, of course. On our English website you can find whatever information you are looking for. You can find flyers and information about these courses in this section. 4. WHAT IS THE SERVICE ADDRESSED TO DISABLED STUDENTS? This service provide support for disabled students. For more information check the webpage http://en.unibg.it/life-unibg/services/disabilities-services - Total exemption from enrolment taxes for those whose disability is assessed at over 66% and extra funding from the Lombardy Region - Specialized Tutoring Service - Personalized equivalent examinations using specific technical services - Handling of requests for technical equipment and specific teaching/learning aids - Co-operation with external organizations 5. -

Curriculum Vitae Davide Torsello

CURRICULUM VITAE DAVIDE TORSELLO PERSONAL DETAILS Born December, 29th 1968, in Lecce, Italy. Married, with 3 children Institutional address: Central European University, Business School Frankel Leo utca 30, 1023 Budapest, Hungary Tel: +36 1 887 5058 Fax: +36 1 887 5005 Email: [email protected] PRESENT POSITION Associate Professor, CEU Business School EDUCATION 1999-2003 PhD Social Anthropology (magna cum laude), Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle/Saale. Title of thesis: ‘Trust, property and social change in a Southern Slovakian village’. Obtained on July 11th 2003. 1998-1999 MSc Social Anthropology, London School of Economics and Political Science. Title of thesis: ‘Continuity and Discontinuity. Social change in post-socialist rural Hungary’. 1996-1998 MA Cultural Anthropology, University of Hirosaki, Japan. Title of thesis: ‘The creation of a social reality in a postwar rural settlement of northeastern Japan’, in Japanese. 1995-1996 Graduate Research Student, University of Hirosaki, Japan 1994-1995 Graduate Research Student, Hokkaido University, Japan 1897-1993 BA Japanese Studies (with honours), Oriental University Institute, Napoli (Italy). Title of thesis: ‘The sea and the mountain in the Japanese folklore’, in Italian. FELLOWSHIPS, SCHOLARSHIPS AND AWARDS 2014 Outstanding Research Award, CEU Budapest 2011 Visiting researcher, Quality of Government Institute, Gothenburg University 2010 Visiting fellow, Aleskanteri Institute, University of Helsinki 2010 Visiting researcher, Quality of Government Institute, -

• Address: Department of Economics, University of Bergamo. • Web-Page

SALVATORE PICCOLO Curriculum Vitae • Address: Department of Economics, University of Bergamo. • Web-page: https://sites.google.com/site/salvatorepiccolohome/ • E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] • Birth: 22th, February, 1976 • Citizenship: Italian Past and Current Positions • 2017-present: Full Professor of Economics, Department of Management, Economics & QM, University of Bergamo. • 2015-2017: Full Professor of Economics, Department of Economics and Finance, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Milano). • 2013: National Habilitation as Full-Professor of Economics and Economic Policy • 2011-2015: Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics and Finance, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Milano). • 2007-2011: Assistant Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, Università Federico II di Napoli. • 2005-2007: Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Università di Salerno. • 2007-2008: Visiting Professor Università di Lausanne. • 2006-2009 Post-doc fellow (IDEI) Toulouse School of Economics Private Sector • 2018- :Academic Affiliate Compass Lexecon Education • 2006 Ph.D. in Economics, Northwestern University (Chicago, US). Main Advisor: Prof. William P. Rogerson. • 2001 Toulouse School of Economics (France): Master Degree in Mathematical Economics (DEA-ECOMATH). Main Advisor: Prof. David Martimort. • 2000 Università di Napoli Federico II (Italy): Master Degree in Economics and Finance (MEF). • 2000 Università di Napoli Federico II (Italy): BA in Economics, summa cum laude Prizes and Scholarships