MAURITANIA-PAD-02272018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code List 11 Invoice Currency

Code list 11 Invoice currency Alphabetical order Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region A BTN Bhutan ngultrum BOB Bolivian boliviano AFN Afghan new afghani BAM Bosnian mark ALL Albanian lek BWP Botswanan pula DZD Algerian dinar BRL Brazilian real USD American dollar BND Bruneian dollar AOA Angolan kwanza BGN Bulgarian lev ARS Argentinian peso BIF Burundi franc AMD Armenian dram AWG Aruban guilder AUD Australian dollar C AZN Azerbaijani new manat KHR Cambodian riel CAD Canadian dollar B CVE Cape Verdean KYD Caymanian dollar BSD Bahamian dollar XAF CFA franc of Central-African countries BHD Bahraini dinar XOF CFA franc of West-African countries BBD Barbadian dollar XPF CFP franc of Oceania BZD Belizian dollar CLP Chilean peso BYR Belorussian rouble CNY Chinese yuan renminbi BDT Bengali taka COP Colombian peso BMD Bermuda dollar KMF Comoran franc Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region CDF Congolian franc CRC Costa Rican colon FKP Falkland Islands pound HRK Croatian kuna FJD Fijian dollar CUC Cuban peso CZK Czech crown G D GMD Gambian dalasi GEL Georgian lari DKK Danish crown GHS Ghanaian cedi DJF Djiboutian franc GIP Gibraltar pound DOP Dominican peso GTQ Guatemalan quetzal GNF Guinean franc GYD Guyanese dollar E XCD East-Caribbean dollar H EGP Egyptian pound GBP English pound HTG Haitian gourde ERN Eritrean nafka HNL Honduran lempira ETB Ethiopian birr HKD Hong Kong dollar EUR Euro HUF Hungarian forint F I Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region ISK Icelandic crown LAK Laotian kip INR Indian rupiah -

AFCP Projects at World Heritage Sites

CULTURAL HERITAGE CENTER – BUREAU OF EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS – U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE AFCP Projects at World Heritage Sites The U.S. Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation supports a broad range of projects to preserve the cultural heritage of other countries, including World Heritage sites. Country UNESCO World Heritage Site Projects Albania Historic Centres of Berat and Gjirokastra 1 Benin Royal Palaces of Abomey 2 Bolivia Jesuit Missions of the Chiquitos 1 Bolivia Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Centre of the Tiwanaku 1 Culture Botswana Tsodilo 1 Brazil Central Amazon Conservation Complex 1 Bulgaria Ancient City of Nessebar 1 Cambodia Angkor 3 China Mount Wuyi 1 Colombia National Archeological Park of Tierradentro 1 Colombia Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena 1 Dominican Republic Colonial City of Santo Domingo 1 Ecuador City of Quito 1 Ecuador Historic Centre of Santa Ana de los Ríos de Cuenca 1 Egypt Historic Cairo 2 Ethiopia Fasil Ghebbi, Gondar Region 1 Ethiopia Harar Jugol, the Fortified Historic Town 1 Ethiopia Rock‐Hewn Churches, Lalibela 1 Gambia Kunta Kinteh Island and Related Sites 1 Georgia Bagrati Cathedral and Gelati Monastery 3 Georgia Historical Monuments of Mtskheta 1 Georgia Upper Svaneti 1 Ghana Asante Traditional Buildings 1 Haiti National History Park – Citadel, Sans Souci, Ramiers 3 India Champaner‐Pavagadh Archaeological Park 1 Jordan Petra 5 Jordan Quseir Amra 1 Kenya Lake Turkana National Parks 1 1 CULTURAL HERITAGE CENTER – BUREAU OF EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS – U.S. DEPARTMENT -

08 Canadian Dollar 90.7 95.9 Central African Rep

Price indices Indices des prix 8 Retail price indices relating to living expenditures of United Nations officials New York City = 100, index date = April 2021 Indices des prix de détail relatif aux dépenses de la vie courante des fonctionnaires de l'ONU New York = 100, date d'indice = avril 2021 National currency per US $ Index - Indice Monnaie nationale du $ E.U. Excluding Country or area - Pays ou zone housing 2 Duty Station Per US $ 1 Currency Non compris Villes-postes Cours du $ E-U 1 Monnaie Total l'habitation 2 Afghanistan Kabul 78.070 Afghani 86.3 93.1 Albania - Albanie Tirana 98.480 Lek 77.6 82.5 Algeria - Algérie Algiers 132.977 Algerian dinar 80.0 85.0 Angola Luanda 643.121 Kwanza 83.6 92.7 Argentina - Argentine Buenos Aires 94.517 Argentine peso 81.4 84.2 Armenia - Arménie Yerevan 518.300 Dram 75.0 80.3 Australia - Australie Sydney 1.291 Australian dollar 82.5 87.9 Austria - Autriche Vienna 0.820 Euro 90.6 99.5 Azerbaijan - Azerbaïdjan Baku 1.695 Azerbaijan manat 80.6 87.4 Bahamas Nassau 1.000 Bahamian dollar 99.5 95.8 Bahrain - Bahreïn Manama 0.377 Bahraini dinar 83.0 85.8 Bangladesh Dhaka 84.735 Taka 81.4 88.9 Barbados - Barbade Bridgetown 2.000 Barbados dollar 89.8 95.2 Belarus - Bélarus Minsk 2.524 New Belarusian ruble 84.9 90.7 Belgium - Belgique Brussels 0.820 Euro 84.0 92.3 Belize Belmopan 2.000 Belize dollar 75.7 80.0 Benin - Bénin Cotonou 537.714 CFA franc 83.4 92.0 Bhutan - Bhoutan Thimpu 72.580 Ngultrum 77.0 83.5 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) - Bolivie (État plurinational de) La Paz 6.848 Boliviano 73.4 80.5 Bosnia -

Diapositive 1

Source: ORIGIN - AFRICA Voyager Autrement en Mauritanie Circuit Les espaces infinis du pays des sages Circuit de 11 jours / 10 nuits Du 08 au 18 mars 2021, du 15 au 25 novembre 2021, Du 7 au 17 mars 2022 (tarifs susceptibles d’être révisés pour ce départ) Votre voyage en Mauritanie A la croisée du Maghreb et de l’Afrique subsaharienne, la Mauritanie est un carrefour de cultures, et ses habitants sont d’une hospitalité et d’une convivialité sans pareils. Oasis, source d’eau chaude, paysages somptueux de roches et de dunes…, cette destination vous surprendra par la poésie de ses lieux et ses lumières changeantes. Ce circuit vous permettra de découvrir les immensités sahariennes et les héritages culturels de cette destination marquée par sa diversité ethnique. Depuis Nouakchott, vous emprunterez la Route de l’Espoir pour rejoindre les imposants massifs tabulaires du Tagant et vous régaler de panoramas splendides. Vous rejoindrez l’Adrâr et ses palmeraies jusqu’aux dunes de l’erg Amatlich, avant d’arriver aux villages traditionnels de la Vallée Blanche. Après avoir découvert l’ancienne cité caravanière de Chinguetti, vous échangerez avec les nomades pour découvrir la vie dans un campement. Vous terminerez votre périple en rejoignant la capitale par la cuvette de Yagref. Ceux qui le souhaitent pourront poursuivre leur voyage par une découverte des Bancs d’Arguin. VOYAGER AUTREMENT EN MAURITANIE…EN AUTREMENT VOYAGER Les points forts de votre voyage : Les paysages variés des grands espaces Les anciennes cités caravanières La découverte de la culture nomade Source: ORIGIN - AFRICA Un groupe limité à 12 personnes maximum Circuit Maroc Algérie Mauritanie Chinguetti Atar Adrar Tounguad Ksar El Barka Mali Nouakchott Moudjeria Sénégal Les associations et les acteurs de développement sont des relais privilégiés pour informer les voyageurs sur les questions de santé, d’éducation, de développement économique. -

African Development Bank Group Project : Mauritania

Language: English Original: French AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : MAURITANIA – AGRICULTURAL TRANSFORMATION SUPPORT PROJECT (PATAM) COUNTRY : ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF MAURITANIA PROJECT APPRAISAL REPORT Main Report Date: November 2018 Team Leader: Rafâa MAROUKI, Chief Agro-economist, RDGN.2 Team Members: Driss KHIATI, Agricultural Sector Specialist, COMA Beya BCHIR, Environmentalist, RDGN.3 Sarra ACHEK, Financial Management Specialist, SNFI.2 Saida BENCHOUK, Procurement Specialist, SNFI.1-CODZ Elsa LE GROUMELLEC, Principal Legal Officer, PGCL.1 Amel HAMZA, Gender Specialist, RDGN.3 Ibrahima DIALLO, Disbursements Expert, FIFC.3 Project Selima GHARBI, Disbursements Officer, RDGN/FIFC.3 Team Hamadi LAM, Agronomist (Consultant), AHAI Director General: Mohamed EL AZIZI, RDGN Deputy Director General: Ms Yacine FAL, RDGN Sector Director: Martin FREGENE, AHAI Division Manager: Vincent CASTEL, RDGN.2 Division Manager: Edward MABAYA, AHAI.1 Khaled LAAJILI, Principal Agricultural Economist, RDGC; Aminata SOW, Rural Peer Engineering Specialist, RDGW.2; Laouali GARBA, Chief Climate Change Specialist, Review: AHAI.2; Osama BEN ABDELKARIM, Socio-economist, RDGN.2. TABLE OF CONTENTS Equivalents, Fiscal Year, Weights and Measures, Acronyms and Abbreviations, Project Information Sheet, Executive Summary, Project Matrix ……….…………………...………..……... i - v I – Strategic Thrust and Rationale ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Project Linkage with Country Strategy and -

Mauritania - Senegal: an Emerging New African Gas Province – Is It Still Possible?

October 2020 Mauritania - Senegal: an emerging New African Gas Province – is it still possible? OIES PAPER: NG163 Mostefa Ouki, Senior Research Fellow, OIES The contents of this paper are the author’s sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2020 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78467-165-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26889/9781784671655 i Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. ii Tables ...................................................................................................................................................... ii Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 3 NATURAL GAS POTENTIAL ................................................................................................................. -

Le Guide Africain Des Marchés Ą Revenu Fixe

88 – Mauritania Mauritania 2006 At a Glance Population (mn) 3.2 Population Growth (annual %) 2.9 Pico de� a Gran Canaria ued D râ Gomera Teide� O 3715 m Official Language (s) Arabic Hierro Cap Juby 1949 m Las Palmas de � MAROC MAURITANIE Gran Canaria D E HT A I M N A D D O A � ARCHIPEL DES CANARIES Espagne Tindouf El Aaiún alH am ra UF Currency Ouguiya (MRO) A s Saqu ia t t a h K I l ALGERIE a T d T e O C E A N � u E O Y GDP (Current US$ bn) 2.8 T I 701 m G U ATLANTIQUE R E U S O M M M A K E T S A H A R A � Z N GDP Growth (annual %) 13.9 A H OCCIDENTAL H S L C E E R H Golfe� I E C ¡AMÂDA� de Cintra F T G U KÂGHE– R EL ¡ARICHA O E GDP Per Capita (US$) TT 877 U O Cap Barbas S Fdérik R 518 m Kediet� A R ej Jill� D 915 m E L H A M M Â M I A FDI, net inflows (US$ mn) (2005) 115 MAQ–EÏR Nouâdhibou Guelb� Râs Nouâdhibou er Rîchât� 485 m Râs Agâdîr AZEFFÂLAtâr External Debt (US$ mn) 1,429 OUARÂNE IJÂFENE AKCHÂR Akjoujt Râs Timirist SAHARA External Debt/GDP (%) 51.6 E L M R E Tidjikja Y Nouakchott Y A O U K É Â R CPI Inflation (annual %) 6.4 TRÂRZA Boûmdeïd TAGÂNT Aleg Tamchaket A Rosso Sénég B al 'Ayoûn� Â Kiffa ¡ÔØ IRÎGUI Ç el 'Atroûs Néma A Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) 54.9 Saint Louis Kaédi ' Mbout L Timbedgha Louga E AFOLLÉ Kankossa N iger Ferlo Sélibaby Thiès Gross Official Reserves (US$ bn) - Cap Vert Dakar MALI Diourbel KAARTA Fatick SENEGAL Kayes Mopti Gross Official Reserves (in months of imports) - GEOATLAS - Copyright1998 Graphi-Ogre UNDP HDI RANKing 153 0 km 100 200 300 400 km Source: AfDB, IMF, UNCTAD, UNDP, UN Population Division 1. -

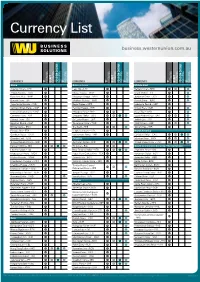

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities September 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

Unemployment

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CONTENTS Acknowledgements . .. ix Abbreviations & Acronyms . xi Executive Summary . xiii Growth and Jobs: Low Productivity, High Demand for Targeted Skills . xiii Youth-related Constraints: Women, Mobility, and Core Competencies . xv Labor Market Programs: A Better Balance between Demand and Supply . xvi Transforming the Youth Employment Trajectory: Toward an Integrated Approach .. xvii Context and Objectives . 1 Conceptual Framework . 2 Approach . 4 Profile of Jobs and Labor Demand . 7 Growth Trends . 7 Types and Quality of Jobs . 9 Labor Costs . 12 Demand for Workforce Skills . 14 Recruitment and Retention . 14 Conclusions . 16 Profile of Youth in the Labor Force . 17 Demographic and Labor Force Trends . 17 Education . 20 Gender . 21 Unemployment . 23 Job Skills and Preferences . 24 Conclusions . 28 MAURITANIA | TRANSFORMING THE JOBS TRAJECTORY FOR VULNERABLE YOUTH iii Landscape of Youth Employment Programs . 29 Mapping Key Labor Market Actors . 29 Youth Employment Expenditure . 30 Active Labor Market Programs . 33 Social Funds for Employment . 33 Vocational Training . 34 Monitoring and Evaluation of Jobs Interventions . 34 Social Protection Systems . 34 Labor Policy Dialogue . 36 Conclusions . 37 Policy Implications: Transforming the Youth Employment Trajectory . 39 Typology of Youth Employment Challenges and Constraints . 39 From Constraints to Opportunities . 40 Toward an Integrated Model for Youth Employment . 48 Conclusions: Equal Opportunity, Stronger Coalitions . 48 Technical Annex . 49 Chapter 1 . 49 Chapter 2. 52 Chapter 3 . 56 Figues, Tables, and Boxes FIGURE 1 Conceptual framework for jobs, economic transformation, and social cohesion . 3 FIGURE 2 Growth outlook for Mauritania, overall and by sector, 2013–2018 . 8 FIGURE 3 Sectoral contribution to GDP and productivity, Mauritania, 1995–2014 . -

Mauritanian Women and Political Power (1960-2014) Céline Lesourd

The lipstick on the edge of the well: Mauritanian women and political power (1960-2014) Céline Lesourd To cite this version: Céline Lesourd. The lipstick on the edge of the well: Mauritanian women and political power (1960- 2014). F. Sadiqi. Women’s Rights in the Aftermath of the Arab Spring„ Palgrave Macmillan, pp.77- 93., 2016. hal-02292993 HAL Id: hal-02292993 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02292993 Submitted on 20 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE LIPSTICK ON THE EDGE OF THE WELL: 1 MAURITANIAN WOMEN AND POLITICAL POWER (1960-2014) Céline Lesourd (Translated from French into English by Fatima Sadiqi) Women at the Meeting An immense wasteland. Deafening music. A colossal scene. Blinding projectors. A crowd of onlookers mingles at the meeting point of militants. Dozens of Land Cruiser VX, Hilux, gleaming new GXs, seek to come closer to the center of action. Drivers honk their horns and young women shout, waving the poster of a candidate. Some motion wildly from the back of pick-ups. All of them wearing light purple veils [melehfa], the winning color of the candidate who will soon become president.