Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pattern Formation in Wootz Damascus Steel Swords and Blades

Indian Journal ofHistory ofScience, 42.4 (2007) 559-574 PATTERN FORMATION IN WOOTZ DAMASCUS STEEL SWORDS AND BLADES JOHN V ERHOEVEN* (Received 14 February 2007) Museum quality wootz Damascus Steel blades are famous for their beautiful surface patterns that are produced in the blades during the forging process of the wootz ingot. At an International meeting on wootz Damascus steel held in New York' in 1985 it was agreed by the experts attending that the art of making these blades had been lost sometime in nineteenth century or before. Shortly after this time the author began a collaborative study with bladesmith Alfred Pendray to tty to discover how to make ingots that could be forged into blades that would match both the surface patterns and the internal carbide banded microstructure of wootz Damascus steels. After carrying out extensive experiments over a period ofaround 10 years this work succeeded to the point where Pendray is now able to consistently make replicas of museum quality wootz Damascus blades that match both surface and internal structures. It was not until near the end of the study that the key factor in the formation of the surface pattern was discovered. It turned out to be the inclusion of vanadium impurities in the steel at amazingly low levels, as low as 0.004% by weight. This paper reviews the development of the collaborative research effort along with our analysis ofhow the low level of vanadium produces the surface patterns. Key words: Damascus steel, Steel, Wootz Damascus steel. INTRODUCTION Indian wootz steel was generally produced by melting a charge of bloomery iron along with various reducing materials in small closed crucibles. -

The White Book of STEEL

The white book of STEEL The white book of steel worldsteel represents approximately 170 steel producers (including 17 of the world’s 20 largest steel companies), national and regional steel industry associations and steel research institutes. worldsteel members represent around 85% of world steel production. worldsteel acts as the focal point for the steel industry, providing global leadership on all major strategic issues affecting the industry, particularly focusing on economic, environmental and social sustainability. worldsteel has taken all possible steps to check and confirm the facts contained in this book – however, some elements will inevitably be open to interpretation. worldsteel does not accept any liability for the accuracy of data, information, opinions or for any printing errors. The white book of steel © World Steel Association 2012 ISBN 978-2-930069-67-8 Design by double-id.com Copywriting by Pyramidion.be This publication is printed on MultiDesign paper. MultiDesign is certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council as environmentally-responsible paper. contEntS Steel before the 18th century 6 Amazing steel 18th to 19th centuries 12 Revolution! 20th century global expansion, 1900-1970s 20 Steel age End of 20th century, start of 21st 32 Going for growth: Innovation of scale Steel industry today & future developments 44 Sustainable steel Glossary 48 Website 50 Please refer to the glossary section on page 48 to find the definition of the words highlighted in blue throughout the book. Detail of India from Ptolemy’s world map. Iron was first found in meteorites (‘gift of the gods’) then thousands of years later was developed into steel, the discovery of which helped shape the ancient (and modern) world 6 Steel bEforE thE 18th cEntury Amazing steel Ever since our ancestors started to mine and smelt iron, they began producing steel. -

Damascus Steel

Damascus steel For Damascus Twist barrels, see Skelp. For the album of blades, and research now shows that carbon nanotubes the same name, see Damascus Steel (album). can be derived from plant fibers,[8] suggesting how the Damascus steel was a type of steel used in Middle East- nanotubes were formed in the steel. Some experts expect to discover such nanotubes in more relics as they are an- alyzed more closely.[6] The origin of the term Damascus steel is somewhat un- certain; it may either refer to swords made or sold in Damascus directly, or it may just refer to the aspect of the typical patterns, by comparison with Damask fabrics (which are in turn named after Damascus).[9][10] 1 History Close-up of an 18th-century Iranian forged Damascus steel sword ern swordmaking. These swords are characterized by dis- tinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water. Such blades were reputed to be tough, re- sistant to shattering and capable of being honed to a sharp, resilient edge.[1] Damascus steel was originally made from wootz steel, a steel developed in South India before the Common Era. The original method of producing Damascus steel is not known. Because of differences in raw materials and man- ufacturing techniques, modern attempts to duplicate the metal have not been entirely successful. Despite this, several individuals in modern times have claimed that they have rediscovered the methods by which the original Damascus steel was produced.[2][3] The reputation and history of Damascus steel has given rise to many legends, such as the ability to cut through a rifle barrel or to cut a hair falling across the blade,.[4] A research team in Germany published a report in 2006 re- vealing nanowires and carbon nanotubes in a blade forged A bladesmith from Damascus, ca. -

Iron, Steel and Swords Script - Page 1 Powder Is Difficult

10.4. Crucible Steel 10.4.1 The Making of Crucible Steel in Antiquity Debunking the Myth of "Wootz" Before I start on "wootz" I want to be very clear on how I see this rather confused topic: There never has been a secret about the making of crucible (or "wootz") steel, and there isn't one now. Recipes for making crucible steel were well-known throughout the ages, and they were just as sensible or strange as recipes for making bloomery iron or other things. There are many ways for making crucible steel. If the crucible process worked properly, the steel produced was fully liquid, and it didn't matter much exactly how you made it. If the process did not work well and the steel was only partially molten, i.e. a mixture of liquid cast iron and solid austenite, the product was not good steel. Besides differences in the (always large) carbon concentration, the concentration of impurities might also be different - just like for bloomery steel. This might lead to differences in properties for comparable carbon concentrations, for example the susceptibility to cold shortness or the ability to form a good "watered silk" or "water" pattern. Crucible steel that has been liquid once is relatively homogeneous and slag-free - in contrast to bloomery steel. That is where crucible steel is "better" than bloomery steel. Crucible steel is always high carbon if not ultra-high carbon steel (UHCS). This is generally not so good. However, mixtures that would, for example, have produced 0.8 % carbon steel, a steel optimal for many applications, would not melt at the temperatures available. -

Pig Iron Sub-Committee, Chaired by Rodrigo Valladares, CEO of Viena Siderúrgica S/A, for Preparing and Editing the Information Presented in This Guide

Copyright © 2014 by International Iron Metallics Association Ltd. This guide published by International Iron Metallics Association Ltd. All rights reserved. This guide may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever providing it includes full acknowledgement to the IIMA. 2011 International Iron Metallics Association (IIMA) Printed and bound in the United Kingdom Disclaimer This guide is intended for information purposes only and is not intended as commercial material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purposes of sale of any financial instrument, is not intended to provide an investment recommendation and should not be relied upon for such. The material is derived from published sources, together with personal research. No responsibility or liability is accepted for any such information of opinions or for any errors, omissions, misstatements, negligence, or otherwise for any further communication, written or otherwise. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The International Iron Metallics Association (IIMA) wishes to thank Dr. Oscar Dam, Chief Technical Advisor, and the Pig Iron Sub-Committee, chaired by Rodrigo Valladares, CEO of Viena Siderúrgica S/A, for preparing and editing the information presented in this guide. FOREWORD The International Iron Metallics Association was created to promote the use of ore-based metallics (pig iron, HBI, DRI, and iron nuggets) as value-adding raw materials for the iron and steel and ferrous casting industries. Safe and efficient handling and shipping of merchant ore-based metallics are vital to the commercial trade and use of these materials. Therefore, we are continuing the series of guides begun by IIMA co-founder, HBI Association (HBIA), with this guide which addresses the methods, techniques, and procedures for handling and transferring merchant pig iron at dry bulk terminals. -

Primary Mill Fabrication

Metals Fabrication—Understanding the Basics Copyright © 2013 ASM International® F.C. Campbell, editor All rights reserved www.asminternational.org CHAPTER 1 Primary Mill Fabrication A GENERAL DIAGRAM for the production of steel from raw materials to finished mill products is shown in Fig. 1. Steel production starts with the reduction of ore in a blast furnace into pig iron. Because pig iron is rather impure and contains carbon in the range of 3 to 4.5 wt%, it must be further refined in either a basic oxygen or an electric arc furnace to produce steel that usually has a carbon content of less than 1 wt%. After the pig iron has been reduced to steel, it is cast into ingots or continuously cast into slabs. Cast steels are then hot worked to improve homogeneity, refine the as-cast microstructure, and fabricate desired product shapes. After initial hot rolling operations, semifinished products are worked by hot rolling, cold rolling, forging, extruding, or drawing. Some steels are used in the hot rolled condition, while others are heat treated to obtain specific properties. However, the great majority of plain carbon steel prod- ucts are low-carbon (<0.30 wt% C) steels that are used in the annealed condition. Medium-carbon (0.30 to 0.60 wt% C) and high-carbon (0.60 to 1.00 wt% C) steels are often quenched and tempered to provide higher strengths and hardness. Ironmaking The first step in making steel from iron ore is to make iron by chemically reducing the ore (iron oxide) with carbon, in the form of coke, according to the general equation: Fe2O3 + 3CO Æ 2Fe + 3CO2 (Eq 1) The ironmaking reaction takes place in a blast furnace, shown schemati- cally in Fig. -

The Future of Steelmaking– Howeuropean the MANAGEMENT SUMMARY

05.2020 The future of steelmaking – How the European steel industry can achieve carbon neutrality MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The future of steelmaking / How the European steel industry can achieve carbon neutrality The European steelmaking industry emits 4% of the EU's total CO2 emissions. It is under growing public, economic and regulatory pressure to become carbon neutral by 2050, in line with EU targets. About 60% of European steel is produced via the so-called primary route, an efficient but highly carbon-intensive production method. The industry already uses carbon mitigation techniques, but these are insufficient to significantly reduce or eliminate carbon emissions. The development and implementation of new technologies is underway. With limited investment cycles left until the 2050 deadline, the European steelmaking industry must decide on which new technology to invest in within the next 5-10 years. We assess the most promising emerging technologies in this report. They fall into two main categories: carbon capture, use and/or storage (CCUS), and alternative reduction of iron ore. CCUS processes can be readily integrated into existing steel plants, but cannot alone achieve carbon neutrality. If biomass is used in place of fossil fuels in the steelmaking process, CCUS can result in a negative carbon balance. Alternative reduction technologies include hydrogen-based direct reduction processes and electrolytic reduction methods. Most are not well developed and require huge amounts of green energy, but they hold the promise of carbon-neutral steelmaking. One alternative reduction process, H2-based shaft furnace direct reduction, offers particular promise due to its emissions-reduction potential and state of readiness. -

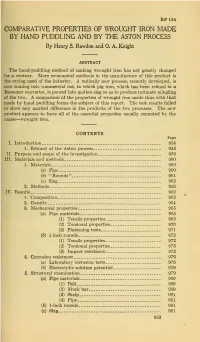

Comparative Properties of Wrought Iron Made by Hand Puddling and by the Aston Process

RP124 COMPARATIVE PROPERTIES OF WROUGHT IRON MADE BY HAND PUDDLING AND BY THE ASTON PROCESS By Henry S. Rawdon and 0. A. Knight ABSTRACT The hand-puddling method of making wrought iron has not greatly changed for a century. More economical methods in the manufacture of thjs product is the crying need of the industry. A radically new process, recently developed, is now coming into commercial use, in which pig iron, which h>as been refined in a Bessemer converter, is poured into molten slag so as to produce intimate mingling of the two. A comparison of the properties of wrought iron made thus with that made by hand puddling forms the subject of this report. The test results failed to show any marked difference in the products of the two processes. The new product appears to have all of the essential properties usually connoted by the name—wrought iron, CONTENTS Page I. Introduction 954 1. Resume of the Aston process 955 II. Purpose and scope of the investigation 959 III. Materials and methods 960 1. Materials 960 (a) Pipe 960 (6) "Rounds" 961 (c) Slag 962 2. Methods 962 IV. Results 962 1. Composition 962 2. Density 964 3. Mechanical properties 965 (a) Pipe materials 965 (1) Tensile properties 965 (2) Torsional properties 970 (3) Flattening tests 971 (6) 1-inch rounds 972 (1) Tensile properties 972 (2) Torsional properties 973 (3) Impact resistance 973 4. Corrosion resistance 976 (a) Laboratory corrosion tests 976 (6) Electrolytic solution potential 979 5. Structural examination 979 (a) Pipe materials 980 (1) BaU 980 (2) Muck bar 980 (3) Skelp 981 (4) Pipe 981 (&) 1-inch rounds 981 (c) Slag 981 953 : 954 Bureau of Standards Journal of Research [vol. -

Final Exam Questions Generated by the Class

Final Exam Questions Generated by the Class Module 8 – Iron and Steel Describe some of the business practices that Carnegie employed that allowed him to take command of the steel industry. Hard driving, vertical integration, price making Which of the following was/is NOT a method used to make steel? A. Puddling B. Bessemer process C. Basic oxygen process D. Arc melting E. None of the above What are the three forms of iron, and what is the associated carbon content of each? Wrought <.2% Steel .2-2.3% Cast Iron 2.3-4.2% How did Andrew Carnegie use vertical integration to gain control of the steel market? Controlled the entire steel making process from mining to final product Who created the best steel for several hundred years while making swords during the 1500’s? A. Syria B. Egypt C. Japan D. England Describe the difference between forging and casting. When forging, you beat and hammer the material into the desired shape. When casting, you pour liquid into a mold to shape it. Describe the difference between steel and wrought iron. Steel has less carbon Which of the following forms of iron has a low melting point and is not forgeable? A. Steel B. Pig Iron C. Wrought Iron D. None of the Above What two developments ushered in the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age? More iron ore and greater ability to change its properties using readily available alloying agent (carbon) 1 Final Exam Questions Generated by the Class What is the difference between ferrite and austenite? A. -

An Explanation of Possible Damascus Steel Manufacturing Based On

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MECHANICS An Explanation of Possible Damascus Steel Manufacturing Based on Duration of Transient Nucleate Boiling Process and Prediction of the Future of Controlled Continuous Casting NIKOLAI KOBASKO Intensive Technologies Ltd, Kyiv, Ukraine and IQ Technologies Inc, Akron, USA Abstract - In the paper the new explanation in cementite microstructure were also found in the manufacturing of Damascus steel, based on discovered archeological items from Pol'tse, a settlement at Amur the specific characteristics of transient nucleate boiling river, V-IV century B.C. Raw materials and Damascus processes, is provided. Also, the future of continuous steel crafting instruction are not longer available. Details casting in the paper is discussed. According to of technology, which was used by the capable discovered characteristics, duration of transient nucleate metallurgists from Pol'tse, is not known [8]. The ancient boiling process is directly proportional to squared size of technique reached modern - day Turkmenistan and a steel part and inversely proportional to thermal Uzbekistan around 900 A.D., and then the Middle East diffusivity of material, depends on configuration and circa 1000 A.D. There are numerous publications where initial temperature of component, thermal properties of this matter is widely discussed [9 - 16]. It is underlined liquid. The surface temperature of steel part during that India has been reputed for its iron and steel since transient nucleate boiling process maintains at the level ancient times, the time of Alexander the Great (356 B.C. of boiling point of liquid and cannot be below it. Based - 323 B.C.) [5] . When Alexander the Great got to India on these characteristics, the new hypothesis regarding he ordered to be delivered to him “100 talents of Indian manufacturing of Damascus steel is proposed according steel” [5]. -

Formation of Faceted Excess Carbides in Damascus Steels Ledeburite Class

Journal of Materials Science and Engineering B 8 (1-2) (2018) 36-44 doi: 10.17265/2161-6221/2018.1-2.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING Formation of Faceted Excess Carbides in Damascus Steels Ledeburite Class Dmitry Sukhanov1 and Natalia Plotnikova2 1. ASK-MSC Company (Metallurgy), Moscow 117246, Russia 2. Novosibirsk State Technical University, Novosibirsk 630073, Russia Abstract: In this research was developed stages of formation troostite-carbide structure into pure Damascus steel ledeburite class type BU22А obtained by vacuum melting. In the first stage of the technological process, continuous carbides sheath was formed along the boundaries of austenitic grains, which morphologically resembles the inclusion of ledeburite. In the second stage of the process, there is a seal and faceted large carbide formations of eutectic type. In the third stage of the technological process, troostite matrix is formed with a faceted eutectic carbide non-uniformly distributed in the direction of the deformation with size from 5.0 μm to 20 μm. It found that the stoichiometric composition of faceted eutectic carbides is in the range of 34 < C < 36 (atom %), which corresponds to -carbide type Fe2C with hexagonal close-packed lattice. Considering stages of transformation of metastable ledeburite in the faceted eutectic -carbides type Fe2C, it revealed that the duration of isothermal exposure during heating to the eutectic temperature, is an integral part of the process of formation of new excess carbides type Fe2C with a hexagonal close-packed lattice. It is shown that troostite-carbide structure Damascus steel ledeburite class (BU22А), with volume fraction of excess -carbide more than 20%, is fully consistent with the highest grades of Indian steels type Wootz. -

Historical Survey of Iron and Steel Production in Bosnia and Herzegovina

UDK 669.1(497.15)(091) ISSN 1580-2949 Professional article/Strokovni ~lanek MTAEC9, 43(4)223(2009) S. MUHAMEDAGI], M. ORU]: HISTORICAL SURVEY OF IRON AND STEEL PRODUCTION IN BiH HISTORICAL SURVEY OF IRON AND STEEL PRODUCTION IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA ZGODOVINSKI PREGLED PROIZVODNJE @ELEZA IN JEKLA V BOSNI IN HERCEGOVINI Sulejman Muhamedagi}1, Mirsada Oru~2 1University of Zenica, Faculty of metallurgy and materials, Travni~ka c. 1, 72000 Zenica, Bosna i Hercegovina 2University of Zenica, Institute of Metallurgy "Kemal Kapetanovi}", Travni~ka c. 1, 72000 Zenica, Bosna i Hercegovina [email protected] Prejem rokopisa – received: 2009-01-08; sprejem za objavo – accepted for publication: 2009-01-16 Cast-iron and steel production facilities were, and still are, frequently located on sites with deposits of iron ore and coal. The center of steel metallurgy in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and of the former Yugoslavia, is located in the Iron and Steel Plant Zenica, today known as Arcelor Mittal Zenica. In this paper the beginning, the development and the planned growth of the iron and steel plant in Zenica is presented with periods of success and periods of crisis. Key words: Iron and Steel Plant Zenica, developmentr, pig iron, steel. Proizvodne naprave za grodelj in jeklo so pogosto zgrajene na le`i{~ih `elezove rude in premoga. Sredi{~e proizvodnje jekla v Bosni in Hercegovini ter v nekdanji Jugoslaviji je bilo v @elezarni Zenica, danes Arcelor Mittal Zenica. V tem sestavku so predstavljeni za~etek, razvoj in na~rtovana rast @elezarne Zenica z obdobji krize in uspeha. Klju~ne besede: @elezarna Zenica, razvoj, grodelj, jeklo advantage of road and railway communications along the 1 INTRODUCTION Bosna valley.