Handbok08.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spitsbergen in Depth

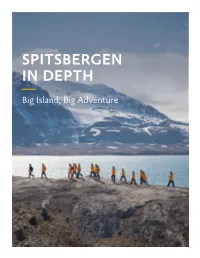

SPITSBERGEN IN DEPTH Big Island, Big Adventure Contents 1 Overview 2 Itinerary 4 Arrival and Departure Details 6 Your Ship 8 Included Activities 9 Adventure Options 10 Dates & Rates 11 Inclusions & Exclusions 13 Your Expedition Team 13 Extend Your Trip 14 Meals on Board 15 Possible Excursions 18 Packing Checklist Overview Spitsbergen in Depth: Big Island, Big Adventure This 14-day journey offers the most extensive exploration of Spitsbergen in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, including the opportunity to witness iconic Arctic wildlife like walrus, reindeer and polar bears, a glimpse into 16th-century EXPEDITION IN BRIEF maritime culture at secluded landing sites, and the rare chance to appreciate breathtaking views at the birdwatching utopias 14th of July Glacier and Alkefjellet. Encounter iconic Arctic wildlife, such as polar bears, walrus and reindeer If conditions allow, we will also attempt a full circumnavigation of the Arctic during this memorable voyage, including a visit to the remote, uninhabited Arctic desert View numerous Arctic bird species, like puffins, Arctic terns and purple of Nordaustlandet. sandpipers The wildlife-viewing opportunities on this trip will leave you with plenty of Take advantage of continuous daylight memories—and photos: the walrus with its long tusks and distinctive whiskers; Explore glaciers, fjords, icebergs and Arctic birds in the thousands—in all their varied majesty; small herds of reindeer more with included Zodiac cruising loping across the tundra; and that most iconic of Arctic creatures, the polar bear, Immerse yourself in the icy realm especially as it prowls the edges of the pack ice on the perpetual hunt for food. -

Our Arctic Nation a U.S

Connecting the United States to the Arctic OUR ARCTIC NATION A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative Cover Photo: Cover Photo: Hosting Arctic Council meetings during the U.S. Chairmanship gave the United States an opportunity to share the beauty of America’s Arctic state, Alaska—including this glacier ice cave near Juneau—with thousands of international visitors. Photo: David Lienemann, www. davidlienemann.com OUR ARCTIC NATION Connecting the United States to the Arctic A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Alabama . .2 14 Illinois . 32 02 Alaska . .4 15 Indiana . 34 03 Arizona. 10 16 Iowa . 36 04 Arkansas . 12 17 Kansas . 38 05 California. 14 18 Kentucky . 40 06 Colorado . 16 19 Louisiana. 42 07 Connecticut. 18 20 Maine . 44 08 Delaware . 20 21 Maryland. 46 09 District of Columbia . 22 22 Massachusetts . 48 10 Florida . 24 23 Michigan . 50 11 Georgia. 26 24 Minnesota . 52 12 Hawai‘i. 28 25 Mississippi . 54 Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. Photo: iStock.com 13 Idaho . 30 26 Missouri . 56 27 Montana . 58 40 Rhode Island . 84 28 Nebraska . 60 41 South Carolina . 86 29 Nevada. 62 42 South Dakota . 88 30 New Hampshire . 64 43 Tennessee . 90 31 New Jersey . 66 44 Texas. 92 32 New Mexico . 68 45 Utah . 94 33 New York . 70 46 Vermont . 96 34 North Carolina . 72 47 Virginia . 98 35 North Dakota . 74 48 Washington. .100 36 Ohio . 76 49 West Virginia . .102 37 Oklahoma . 78 50 Wisconsin . .104 38 Oregon. 80 51 Wyoming. .106 39 Pennsylvania . 82 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE AN ARCTIC NATION? oday, the Arctic region commands the world’s attention as never before. -

Meddelelser120.Pdf (2.493Mb)

MEDDELELSER NR. 120 IAN GJERTZ & BERIT MØRKVED Environmental Studies from Franz Josef Land, with Emphasis on Tikhaia Bay, Hooker Island '-,.J��!c �"'oo..--------' MikhalSkakuj NORSK POLARINSTITUTT OSLO 1992 ISBN 82-7666-043-6 lan Gjertz and Berit Mørkved Printed J uly 1992 Norsk Polarinstitutt Cover picture: Postboks 158 Iceberg of Franz Josef Land N-1330 Oslo Lufthavn (Ian Gjertz) Norway INTRODUCTION The Russian high Arctic archipelago Franz Josef Land has long been closed to foreign scientists. The political changes which occurred in the former Soviet Union in the last part of the 1980s resulted in the opening of this area to foreigners. Director Gennady Matishov of Murmansk Marine Biological Institute deserves much of the credit for this. In 1990 an international cooperation was established between the Murmansk Marine Biological Institute (MMBI); the Arctic Ecology Group of the Institute of Oceanology, Gdansk; and the Norwegian Polar Research Institute, Oslo. The purpose of this cooperation is to develope scientific cooperation in the Arctic thorugh joint expeditions, the establishment of a high Arctic scientific station, and the exchange of scientific information. So far the results of this cooperation are two scientific cruises with the RV "Pomor", a vessel belonging to the MMBI. The cruises have been named Sov Nor-Poll and Sov-Nor-Po12. A third cruise is planned for August-September 1992. In addition the MMBI has undertaken to establish a scientific station at Tikhaia Bay on Hooker Island. This is the site of a former Soviet meteorological base from 1929-1958, and some of the buildings are now being restored by MMBI. -

Handbok07.Pdf

- . - - - . -. � ..;/, AGE MILL.YEAR$ ;YE basalt �- OUATERNARY votcanoes CENOZOIC \....t TERTIARY ·· basalt/// 65 CRETACEOUS -� 145 MESOZOIC JURASSIC " 210 � TRIAS SIC 245 " PERMIAN 290 CARBONIFEROUS /I/ Å 360 \....t DEVONIAN � PALEOZOIC � 410 SILURIAN 440 /I/ ranite � ORDOVICIAN T 510 z CAM BRIAN � w :::;: 570 w UPPER (J) PROTEROZOIC � c( " 1000 Ill /// PRECAMBRIAN MIDDLE AND LOWER PROTEROZOIC I /// 2500 ARCHEAN /(/folding \....tfaulting x metamorphism '- subduction POLARHÅNDBOK NO. 7 AUDUN HJELLE GEOLOGY.OF SVALBARD OSLO 1993 Photographs contributed by the following: Dallmann, Winfried: Figs. 12, 21, 24, 25, 31, 33, 35, 48 Heintz, Natascha: Figs. 15, 59 Hisdal, Vidar: Figs. 40, 42, 47, 49 Hjelle, Audun: Figs. 3, 10, 11, 18 , 23, 28, 29, 30, 32, 36, 43, 45, 46, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 71, 72, 75 Larsen, Geir B.: Fig. 70 Lytskjold, Bjørn: Fig. 38 Nøttvedt, Arvid: Fig. 34 Paleontologisk Museum, Oslo: Figs. 5, 9 Salvigsen, Otto: Figs. 13, 59 Skogen, Erik: Fig. 39 Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani (SNSK): Fig. 26 © Norsk Polarinstitutt, Middelthuns gate 29, 0301 Oslo English translation: Richard Binns Editor of text and illustrations: Annemor Brekke Graphic design: Vidar Grimshei Omslagsfoto: Erik Skogen Graphic production: Grimshei Grafiske, Lørenskog ISBN 82-7666-057-6 Printed September 1993 CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................6 The Kongsfjorden area ....... ..........97 Smeerenburgfjorden - Magdalene- INTRODUCTION ..... .. .... ....... ........ ....6 fjorden - Liefdefjorden................ 109 Woodfjorden - Bockfjorden........ 116 THE GEOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF SVALBARD .... ........... ....... .......... ..9 NORTHEASTERN SPITSBERGEN AND NORDAUSTLANDET ........... 123 SVALBARD, PART OF THE Ny Friesland and Olav V Land .. .123 NORTHERN POLAR REGION ...... ... 11 Nordaustlandet and the neigh- bouring islands........................... 126 WHA T TOOK PLACE IN SVALBARD - WHEN? .... -

Russian High Arctic

RUSSIAN HIGH ARCTIC Rarely visited today yet significant in the history of polar exploration, Franz Josef Land is worthy of its legendary reputation. This extraordinary expedition to Franz Josef Land is as unique and authentic as the place itself. Starting in Longyearbyen in the Norwegian territory of Svalbard, we cross the icy, wildlife-rich Barents Sea to the Russian High Arctic. In Franz Josef Land we discover unparalleled landscapes, wildlife, and history in one of the wildest and most remote corners of the Arctic. The archipelago, part of the Russian Arctic National Park since 2012, is a nature sanctuary. Polar bears and other like Bell Island, Cape Flora, and Cape Tegetthoff we have the quintessential High Arctic wildlife--such as walruses and some opportunity to walk in the footsteps of Fridtjof Nansen, Frederick rare whale species--can be spotted anytime, anywhere in and George Jackson, Julius von Payer, and other polar explorers. At around Franz Josef Land. Scree slopes and cliffs around the Tikhaya Bukhta we find the ruins of a Soviet-era research facility islands host enormous nesting colonies of migratory seabirds that was also a major base for polar expeditions. Across the such as guillemots, dovekies, and ivory gulls. We'll take archipelago there are monuments, memorials, crosses, and the advantage of the 24-hour daylight to exploit every opportunity remains of makeshift dwellings, all testimony to incredible for wildlife viewing. historical events. In Franz Josef Land we encounter a stark and enigmatic RATES INCLUDE: landscape steeped in the drama and heroism of early polar Group transfer to the ship on day of embarkation; exploration. -

POMOR N News Slett

2016 POMOR Newsletter Issue No 5, February 2016 www.pomor.spbu.ru 16.04.2016 their motivation and zest for action and be Editorial in touch in the future. We wish them good luck for their further development, whether Traditionally by the turn of the year in their career or in their private life. POMOR releases its Newsletter in order to In 2015, POMOR turned 14 years old. We report about its progress during the last already have educated around 90 students, year or two (or even three), to give the which means about 5500 active teaching graduates and students the opportunity to hours in specific modules, without share their experience with the whole counting the courses of the Core Module, POMOR community and its network, to tutorials and self‐learning, performed by introduce the new students, to show them circa 130 lecturers from at least 15 research the wide palette of possibilities during and institutions in Russia and in Germany. Our after the studies, and just to inform its old alumni network connects Europe and range and new friends about how things are to Canada and Australia. We thank all going and to sum up the achievements. partners and organizations which have In 2014 and 2015, our students (POMOR VI, been supporting us during the last 14 years 2013‐2015) cut their teeth in their first and hope to continue this way in the research expeditions aboard POLARSTERN future. (ARK‐XXVIII/4), VIKTOR BUYNITSKY Nadezhda Kakhro (TRANSDRIFT XXII), EUROFLEETS‐2, on the research station in the delta of Lena UPDATE: POMOR graduates from three -

Explorateur Et Peintre De L'arctique

Le Nord et la fascination du sublime. Julius Payer (1841-1915), explorateur et peintre de l’Arctique Mathilde Roussat Université de Paris X-Nanterre (France) et Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (Allemagne) Résumé – Julius Payer (1841-1915) compte parmi les grandes figures de l’exploration polaire. Mais il fut aussi, dans les années 1880-1890, un peintre reconnu pour des œuvres inspirées par son expérience du Grand Nord. Abandonnant l’approche scientifique, Payer tenta de faire de l’Arctique un nouveau sujet pour l’art. L’analyse de ses réalisations permet d’en faire ressortir l’allégeance aux pratiques académiques et le tribut payé à un sublime à la fois terrible et magnifique. L’aveu d’échec formulé par l’artiste à la fin du siècle articule enfin de manière décisive nordicité et sublimité en établissant le pôle comme irreprésentable et en suggérant sa dimension métaphysique. L’hostilité des contrées polaires a longtemps fait envisager ces territoires sous l’angle du seul défi technique et scientifique. Lieu de mise à l’épreuve des explorateurs, quand ce n’est pas de leur disparition tragique, l’Arctique reste jusqu’au début du XXe siècle une terre pratiquement inconnue dont la connaissance et la maîtrise se dérobent malgré les assauts répétés d’expéditions initiées par les différentes nations occidentales. Si l’exploration a été, pendant un temps, le fait de commerçants en quête de nouveaux territoires de pêche ou de nouvelles voies maritimes, les bénéfices de ces initiatives sont en effet devenus très vite bien trop hasardeux en regard des risques encourus. À partir du XIXe siècle, ce sont donc les États européens et nord-américains qui reprennent le flambeau d’investigations animées par l’espoir patriotique de voir le succès d’une expédition affirmer la supériorité technique de la nation commanditaire. -

The East Greenland Current North of Denmark Strait: Part I'

The East Greenland Current North of Denmark Strait: Part I' K. AAGAARD AND L. K. COACHMAN2 ABSTRACT.Current measurements within the East Greenland Current during winter1965 showed that above thecontinental slope there were large on-shore components of flow, probably representing a westward Ekman transport. The speed did not decrease significantly with depth, indicatingthat the barotropic mode domi- nates the flow. Typical current speeds were10 to 15 cm. sec.-l. The transport of the current during winter exceeds 35 x 106 m.3 sec-1. This is an order of magnitude greater than previous estimates and, although there may be seasonal fluctuations in the transport, it suggests that the East Greenland Current primarily represents a circulation internal to the Greenland and Norwegian seas, rather than outflow from the central Polarbasin. RESUME. Lecourant du Groenland oriental au nord du dbtroit de Danemark. Aucours de l'hiver de 1965, des mesures effectukes danslecourant du Groenland oriental ont montr6 que sur le talus continental, la circulation comporte d'importantes composantes dirigkes vers le rivage, ce qui reprksente probablement un flux vers l'ouest selon le mouvement #Ekman. La vitesse ne diminue pas beau- coup avec laprofondeur, ce qui indique que le mode barotropique domine la circulation. Les vitesses typiques du courant sont de 10 B 15 cm/s-1. Au cows de l'hiver, le debit du courant dkpasse 35 x 106 m3/s-1. Cet ordre de grandeur dkpasse les anciennes estimations et, malgrC les fluctuations saisonnihres possibles, il semble que le courant du Groenland oriental correspond surtout B une circulation interne des mers du Groenland et de Norvhge, plut6t qu'8 un Bmissaire du bassin polaire central. -

Arctic Explorer - Franz Josef Land, Spitsbergen & East Greenland Expedition

ARCTIC EXPLORER - FRANZ JOSEF LAND, SPITSBERGEN & EAST GREENLAND EXPEDITION Get away from it all on our 19-day Arctic Explorer cruise from Norway to Iceland via the remote Russian archipelago of Franz Josef Land in the Russian High Arctic where pioneers and scientists stepped ashore. This remarkable journey takes you past Spitsbergen’s towering glaciers calving spectacular icebergs across the Greenland Sea to Iceland, the land of fire and ice. Watch polar bears carrying their cubs and fluking whales in the icy waters. Join us on our voyage of discovery as we sail from ice-bound islands to hot springs, spouting geysers and gushing waterfalls. ITINERARY DAY 1, TROMSO Known as the Arctic gateway, Tromso is a remote Norwegian city at 69° north, 250 miles above the Arctic Circle, where you can take in the soft glow of the midnight sun. Make time to attend a midnight concert at Tromso’s distinctive Arctic Cathedral or learn more about early polar explorations at the Polar Museum. Famed for the Northern Lights on winter nights, you can find out more about this natural spectacle at the Science Centre. DAY 2 - DAY 3, AT SEA As you cruise to your next port of call, spend the day at sea savouring the ship’s facilities and learning about your destination’s many facets from the knowledgeable onboard experts. Listen to an enriching talk, indulge in a relaxing treatment at the spa, work out in the well-equipped gym, enjoy some down- time in your cabin, share travel reminiscences with newly found friends: the options are numerous. -

Erik the Red's Land

In May this year, a Briton named Alex Hartley gamely claimed as his personal territory a tiny island in Sval- bard that had been revealed by retreating ice. Sval bard’s islands have a long history of claims and counter-claims by adventurers of diverse nations: the question of who owns the Arctic is an old one. In this next article in our unreviewed biographical/historical series, Frode Skarstein describes Norway’s bid to wrest a corner of Greenland from the Danish crown 75 years ago. Erik the Red’s Land: the land that never was Frode Skarstein Norwegian Polar Institute, Polar Environmental Centre, NO-9296 Tromsø, Norway, [email protected]. “Saturday, 27th of June, 1931. Eventful day. A long coded telegram late last night that I deciphered during the night. At fi ve pm we hoisted the fl ag and occupied the land from Calsbergfjord to Besselsfjord. It will be exciting to see how it develops.” (Devold 1931: author’s translation.) Although not as pithy as the Unity’s log entry from 1616—“Cape Hoorn in 57° 48' S. Rounded 8 p.m.”—when the southern tip of the Americas was fi rst rounded (Hough 1971), the above diary entry by Hallvard Devold is still a salient understatement given the context in which it was made. The next day Devold sent the following telegram to a select few Norwegian newspapers: “In the presence of Eiliv Herdal, Tor Halle, Ingvald Strøm and Søren Rich- ter, the Norwegian fl ag has been hoisted today in Myggbukta. And the land between Carls berg fjord to the south and Bessel fjord to the north occupied in His Pawns in their game: Devold (left) and fellow expe di tion mem bers during the Majesty King Haakon’s name. -

On a Revised Map of Kaiser Franz Josef Land, Based on Oberlieutenant Payer's Original Survey Author(S): Ralph Copeland Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

On a Revised Map of Kaiser Franz Josef Land, Based on Oberlieutenant Payer's Original Survey Author(s): Ralph Copeland Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Aug., 1897), pp. 180-191 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1774601 Accessed: 27-06-2016 04:21 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 128.197.26.12 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 04:21:08 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 180 ON A REVISED MAP OF KAISER FRANZ JOSEF LAND, be used; but things turned out far otherwise, the Nansen sledges taken were seldom available, and the want of Samoyede sledges added greatly to the difficulties of transport. It was found that the north and south parts of the island, except for a belt along the western shore of Wijdo bay, were chiefly covered with immense accumulations of ice, while the central part was a region of boggy valleys and mountain ridges, with occasional more or less fertile slopes. -

NORTH POLE the Ultimate Arctic Adventure Contents

NORTH POLE The Ultimate Arctic Adventure Contents 1 Overview 2 Itinerary 4 Arrival and Departure Details 6 Your Ship 8 Included Activities 10 Adventure Option 11 Dates and Rates 12 Inclusions and Exclusions 13 Your Expedition Team 14 Extend Your Trip 15 Meals on Board 16 Possible Excursions 19 Packing Checklist Per prenotazioni ed informazioni - Ruta 40 Tour Operator - +39 011 7718046 - [email protected] Overview A magical destination for travelers everywhere, the North Pole is special not only EXPEDITION IN BRIEF because of the unique geographical spot it occupies, but also because it remains Stand at the top of the world at 90°N a domain that, for most, exists only in the imagination—fewer people have stood Experience the most powerful at the North Pole than have attempted to climb Mount Everest. Difficult to reach nuclear icebreaker in the world, and singular in its impact, the North Pole transforms the perspectives of everyone 50 Years of Victory fortunate enough to reach it. In 2021, we mark 30 years of taking passengers to this Enjoy helicopter sightseeing above the frozen Arctic Ocean northernmost point on the globe, and on this amazing voyage, we enable you to Possibly view polar bears, join the privileged few who have set foot on the North Pole. walrus and other Arctic wildlife Experience the thrill of the most powerful nuclear icebreaker on the planet Take advantage of optional crushing through thick, multi-year pack ice as it pushes toward 90° north. Enjoy a tethered flight by hot air balloon (weather permitting) riveting helicopter tour over the icy Arctic Ocean; discover the remarkable sights Cruise in a Zodiac of Franz Josef Land; observe the majestic creatures who make their home in this Visit Franz Josef Land historical breathtaking yet fragile land; and experience a dreamlike hot air balloon ride over sites, wildlife and wildflowers the surreal Arctic landscape, an activity offered by no other polar operator.