University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trade and Improving the Coitions of Access for Its Products to the Community Market

No L 141/98 Official Journal of the European Communities 28 . 5 . 76 INTERIM AGREEMENT between the European Economic Community and the Kingdom of Morocco THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, of the one part, and HIS MAJESTY THE KING OF MOROCCO, of the other part, PREAMBLE WHEREAS a Cooperation Agreement between the European Economic Community and the Kingdom of Morocco was signed this day in Rabat; WHEREAS pending the entry into force of that Agreement, certain provisions of the Agreement relating to trade in goods should be implemented as speedily as possible by means of an Interim Agreement, HAVE DECIDED to conclude this Agreement, and to this end have designated as their Plenipotentiaries : THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES : Gaston THORN, President-in-Office of the Council of the European Communities, President and Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg ; Claude CHEYSSON, Member of the Commission of the European Communities ; THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO, Dr Ahmed LARAKI, Minister of State responsible for Foreign Affairs. TITLE I a view to increasing the rate of growth of Morocco's trade and improving the coitions of access for its products to the Community market. TRADE COOPERATION A. Industrial products Article 1 Article 2 The object of this Agreement is to promote trade between the Contracting Parties, taking account of 1 . Subject to the special provisions of Articles 4, their respective levels of development and of the 5 and 7, products originating in Morocco which are need to ensure a better balance in their trade, with not listed in Annex II to the Treaty establishing the 28 . -

Liste Des Medecins Specialists

LISTE DES MEDECINS SPECIALISTS N° NOM PRENOM SPECIALITE ADRESSE ACTUELLE COMMUNE 1 MATOUK MOHAMED MEDECINE INTERNE 130 LOGTS LSP BT14 PORTE 122 BAGHLIA 2 DAFAL NADIA OPHTALMOLOGIE CITE EL LOUZ VILLA N° 24 BENI AMRANE 3 HATEM AMEL GYNECOLOGIE OBSTETRIQUE RUE CHAALAL MED LOT 02 1ERE ETAGE BENI AMRANE 4 BERKANE FOUAD PEDIATRIE RUE BOUIRI BOUALELM BT 01 N°02 BOR DJ MENAIEL 5 AL SABEGH MOHAMED NIDAL UROLOGIE RUE KHETAB AMAR , BT 03 , 1ER ETAGE BORDJ MENAIEL 6 ALLAB OMAR OPHTALMOLOGIE CITE 250 LOGTS, BT N ,CAGE 01 , N° 237 BORDJ MENAIEL 7 AMNACHE OMAR PSYCHIATRIE CITE 96 LOGTS , BT 03 BORDJ MENAIEL 8 BENMOUSSA HOCINE OPHTALMOLOGIE CITE MADAOUI ALI , BT 08, 1ER ETAGE BORDJ MENAIEL 9 BERRAZOUANE YOUCEF RADIOLOGIE CITE ELHORIA ,LOGTS N°03 BORDJ MENAIEL 10 BOUCHEKIR BADIA GYNECOLOGIE OBSTETRIQUE CITE DES 250 LOGTS, N° 04 BORDJ MENAIEL 11 BOUDJELLAL MOHAMMED OUALI GASTRO ENTEROLOGIE CITE DES 92 LOGTS, BT 03, N° 01 BORDJ MENAIEL 12 BOUDJELLAL HAMID OPHTALMOLOGIE BORDJ MENAIEL BORDJ MENAIEL 13 BOUHAMADOUCHE HAMIDA GYNECOLOGIE OBSTETRIQUE RUE AKROUM ABDELKADER BORDJ MENAIEL 14 CHIBANI EPS BOUDJELLI CHAFIKA MEDECINE INTERNE ZONE URBAINE II LOT 55 BORDJ MENAIEL 15 DERRRIDJ HENNI RADIOLOGIE COPPERATIVE IMMOBILIERE EL MAGHREB ALARABI BORDJ MENAIEL 16 DJEMATENE AISSA PNEUMO- PHTISIOLOGIE CITE 24 LOGTS BTB8 N°12 BORDJ MENAIEL 17 GOURARI NOURREDDINE MEDECINE INTERNE RUE MADAOUI ALI ECOLE BACHIR EL IBRAHIMI BT 02 BORDJ MENAIEL 18 HANNACHI YOUCEF ORL CITE DES 250 LOGTS BT 31 BORDJ MENAIEL 19 HUSSAIN ASMA MEDECINE INTERNE 78 RUE KHETTAB AMAR BORDJ MENAIEL 20 -

Magic Mike August 2012

MAGA MAGIC MIKE AUGUST 2012... ““UnnhheessiiittaattiiinngglllyyThheeReexxiiisstthheebbeessttcciiinneemaaIIIhhaavveeeevveerrkknnoownn…”” ((SSuunnddaayyTiiimeess2012)) ““ppoossssiiibblllyyBrriiittaaiiinn’’’ssmoossttbbeeaauuttiiiffuulllcciiinneemaa.........””((BBC)) AUGUST 2012 Issue 89 www.therexberkhamsted.com 01442 877759 Mon-Sat 10.30-6pm Sun 4.30-5.30pm To advertise email [email protected] INTRODUCTION Gallery 4-5 BEST IN AUGUST August Evenings 11 Coming Soon 26 August Films at a glance 26 August Matinees 27 Rants and Pants 42-43 SEAT PRICES (+ REX DONATION £1.00) Circle £8.00+1 Concessions £6.50+1 At Table £10.00+1 Concessions £8.50+1 Royal Box (seats 6) £12.00+1 From infidelity in Caramel, Nadine takes her or for the Box £66.00+1 All matinees £5, £6.50, £10 (box) +1 women to war. Where Do We Go Now BOX OFFICE : 01442 877759 Mon to Sat 10.30 – 6.00 Mon 6 7.30. Egypt/France/Italy/Lebanon 2012 Sun 4.30 – 6.30 FILMS OF THE MONTH Disabled and flat access: through the gate on High Street (right of apartments) Some of the girls and boys you see at the Box Office and Bar: Dayna Archer Liam Parker Julia Childs Amberly Rose Ally Clifton Georgia Rose Nicola Darvell Sid Sagar Romy Davis Liam Stephenson Karina Gale Tina Thorpe Ollie Gower Beth Wallman Elizabeth Hannaway Jack Whiting Billie Hendry-Hughes Olivia Wilson Thanks to McConaughey's oily power, it's not Abigail Kellett Roz Wilson Amelia Kellett Keymea Yazdanian all sex, violence & chicken legs. Lydia Kellett Yalda Yazdanian Killer Joe Fri 3 7.30/Sat 4 7.00 USA 2012 Ushers: Amy, Amy P, Annabel, Ella, Ellie, Ellen W, Hannah, India, James, Kitty, Luke, Meg, Tyree Sally Rowbotham In charge Alun Rees Chief projectionist (Original) Jon Waugh 1st assistant projectionist Martin Coffill Part-time assistant projectionist Anna Shepherd Part-time assistant projectionist Jacquie Rose Chief Admin Oliver Hicks Best Boy Simon Messenger Writer Jack Whiting Writer "Like a whole series of The Wire in a single Jane Clucas & Lynn Hendry PR/Sales/FoH film..."?? Luckily it's French. -

Liste Chirurgiens-Dentistes – Wilaya De Boumerdes

LISTE CHIRURGIENS-DENTISTES – WILAYA DE BOUMERDES N° NOM PRENOM ADRESSE ACTUELLE COMMUNE DAIRA 1 AMARA DAHBIA CITE NOUVELLE N°27 HAMADI KHEMIS EL KHECHNA 2 AISSAOUI HASSIBA RUE ZIANE LOUNES N°04 2EME ETAGE BORDJ-MENAIEL BORDJ-MENAIEL 3 ASSAS SADEK HAI ALLILIGUIA N° 34 BIS BOUMERDES BOUMERDES 4 ABIB KAHINA MANEL CITE DES 850 LOGTS BT 16 N°02 BOUDOUAOU BOUDOUAOU 5 ABBOU EPS GOURARI FERIEL HAI EL MOKHFI LOT N° 02 PORTE N° 01 OULED HADADJ BOUDOUAOU 6 ADJRID ASMA HAI 20 AOUT LOT N°181 OULED MOUSSA KHEMIS EL KHECHNA 7 ADJRID HANA COP- IMMOB EL AZHAR BT 22 1ER ETAGE A DROITE BOUDOUAOU BOUDOUAOU 9 AZZOUZ HOURIA CITE 11 DECEMBRE 1960 BT 06 N°04 BOUMERDES BOUMERDES 10 AZZEDDINE HOURIA LOTISSEMENT II VILLA N°213 BORDJ-MENAIEL BORDJ-MENAIEL 11 ALLOUCHE MOULOUD RUE ABANE RAMDANE DELLYS DELLYS 12 AOUANE NEE MOHAD SALIHA OULED HADADJ OULED HADADJ BOUDOUAOU 13 ALLOUNE DJAMEL CITE 850 LOGTS BT 37 N°02 BOUDOUAOU BOUDOUAOU 14 ACHLAF AHCENE 4, RUE ALI KHOUDJA N°1A TIDJELABINE BOUMERDES 15 ARAB AMINA CITE DES 200 LOGTS BT B1 CAGE B N°03 OULED MOUSSA KHEMIS EL KHECHNA 16 AIT AMEUR EPSE ARIB NACERA CITE DES 850 LOGTS BT 16 N°02 BOUDOUAOU BOUDOUAOU KARIMA AICHAOUI HASSIBA RUE ZIANE LOUNES N°04 2EME ETAGE BORDJ-MENAIEL BORDJ-MENAIEL 17 ARGOUB KENZA CITE DES 82 LOGTS BT A N°05 ISSER ISSER 18 ALOUACHE NORA CITE 919 LOGTS BT 20 N°10S TIDJELABINE BOUMERDES 19 BERRABAH HICHAM CITE 20 AOUT BT J N°92 BOUMERDES BOUMERDES 20 BRADAI KHALIDA 20 RUE FAHAM DJILLALI KHEMIS EL KHECHNA KHEMIS EL KHECHNA 21 BENINAL LYNDA CITE 200 LOGTS 70 BIS N°02 OULED MOUSSA KHEMIS EL KHECHNA -

The Fifth Republic at Fifty

Franco-Maghrebi Crossings International Conference November 3-5, 2011 Winthrop-King Institute for Contemporary French and Francophone Studies Florida State University, Tallahassee Conference Director: Alec G. Hargreaves Administrative Coordinator: Racha Sattati Program All sessions take place in the Diffenbaugh Building on the FSU campus. Details are subject to change. THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 3 11:45AM, 12:30PM, 1:15PM – Complimentary Bus from Hotel Duval (pick-up at North Monroe entrance) to FSU Campus 12:00 noon-6:00 pm – Registration, 4th floor, Diffenbaugh 1:30 pm-3:00 pm – Panels 1A, 1B, 1C Panel 1A, Diffenbaugh 009 From Colonial Conquest to Decolonization Chair: Lindsey Scott (FSU) Alisha Valani (University of Toronto) - Entre brassage et homogénéité : colonisation, exil et folie au Maghreb Jennifer Fredette (SUNY Albany) and Richard Fogarty (SUNY Albany) - Forever apart: Enduring themes of “otherness” in French discourse on North African Muslims and Islam, 1914-1918 and 1989-2011 Doris Gray ( Florida State University) - Tunisia after the revolution: the end of post- colonialism? Panel 1B, Diffenbaugh 129 Memory I Chair: Robyn Cope (FSU) Janice Gross (Grinnell College) - Slimane Benaïssa: Performing the Tightrope of Franco-Algerian Memory Eveline Caduc (Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis) - « Un futur pour héritages déterritorialisés » Patricia Reynaud (School of Foreign Service-Qatar Georgetown University) - Fractures et cicatrices dans Bent Keltoum Panel 1C, Diffenbaugh 005 Women Writers Chair: Virginia Osborn (FSU) Oana Panaite -

2 Days in NEW York PRESENTED by ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY

The Premieres program showcases some of the most highly anticipated dramatic films of the coming year. Catch world premieres and the latest work from established directors at the Sundance Film Festival before they create a splash at local theatres. 2 DAYS IN New York DIRECTOR: Julie Delpy France, 2011, 91 min., color English and French with English subtitles Marion and Mingus live cozily—perhaps too cozily—with their cat and two young children from previous relationships. However, when Marion’s jolly father (played by director Delpy’s real-life dad), her oversexed sister, and her sister’s outrageous boyfriend unceremoniously descend upon them for a visit, it initiates two unforgettable days that will test Marion and Mingus’s relationship. With their unwitting racism and sexual frankness, the French triumvirate hilariously has no boundaries or filters . and no person is left unscathed in its wake. Directed and cowritten by Julie Delpy, 2 Days in New York is a deliciously PRESENTED by Entertainment Weekly witty romp. One of the pleasures of this follow-up film to 2 Days in Paris is the addition of Chris Rock, who—amid the Gallic mayhem—convincingly plays the straight man as Marion’s hipster American boyfriend. With great skill and energy, Delpy heightens cultural differences to comedic extremes but also manages to show that sometimes change is the best solution to a relationship that’s been pushed to its limit.—K.Y. Pr: Christophe Mazodier Ci: Lubomir Bakchev Ed: Isabelle Devinck PrD: Judy Rhee Wr: Julie Delpy, Alexia Landeau Principal Cast: Julie Delpy, Chris Rock, Albert Delpy, Alexia Landeau, Alex Nahon Monday, January 23, 6:30 p.m. -

ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 28 November 2016

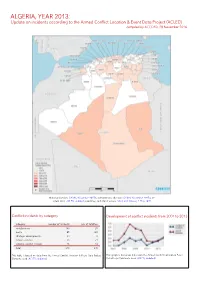

ALGERIA, YEAR 2013: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 28 November 2016 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2004 to 2013 category number of incidents sum of fatalities riots/protests 149 25 battle 85 282 strategic developments 34 0 remote violence 26 21 violence against civilians 16 12 total 310 340 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). ALGERIA, YEAR 2013: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 28 NOVEMBER 2016 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Adrar, 27 incidents killing 62 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Adrar, Bordj Badji Mokhtar, Ouaina, Sbaa, Tanezrouft, Tanezrouft Desert, Timiaouine, Timimoun. In Alger, 56 incidents killing 8 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Algiers, Bab El Oued, Baraki, Kouba, Said Hamdine. -

Terrorism in North Africa and the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach and Implications

TTeerrrroorriissmm iinn NNoorrtthh AAffrriiccaa && tthhee SSaahheell iinn 22001122:: GGlloobbaall RReeaacchh && IImmpplliiccaattiioonnss Yonah Alexander SSppeecciiaall UUppddaattee RReeppoorrtt FEBRUAR Y 2013 Terrorism in North Africa & the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach & Implications Yonah Alexander Director, Inter-University Center for Terrorism Studies, and Senior Fellow, Potomac Institute for Policy Studies February 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Yonah Alexander. Published by the International Center for Terrorism Studies at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced, stored or distributed without the prior written consent of the copyright holder. Manufactured in the United States of America INTER-UNIVERSITY CENTER FO R TERRORISM STUDIES Potomac Institute For Policy Studies 901 North Stuart Street Suite 200 Arlington, VA 22203 E-mail: [email protected] Tel. 703-525-0770 [email protected] www.potomacinstitute.org Terrorism in North Africa and the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach and Implications Terrorism in North Africa & the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach & Implications Table of Contents MAP-GRAPHIC: NEW TERRORISM HOTSPOT ........................................................ 2 PREFACE: TERRORISM IN NORTH AFRICA & THE SAHEL .................................... 3 PREFACE ........................................................................................................ 3 MAP-CHART: TERRORIST ATTACKS IN REGION SINCE 9/11 ....................... 3 SELECTED RECOMMENDATIONS -

Cortés After the Conquest of Mexico

CORTÉS AFTER THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO: CONSTRUCTING LEGACY IN NEW SPAIN By RANDALL RAY LOUDAMY Bachelor of Arts Midwestern State University Wichita Falls, Texas 2003 Master of Arts Midwestern State University Wichita Falls, Texas 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2013 CORTÉS AFTER THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO: CONSTRUCTING LEGACY IN NEW SPAIN Dissertation Approved: Dr. David D’Andrea Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael Smith Dr. Joseph Byrnes Dr. James Cooper Dr. Cristina Cruz González ii Name: Randall Ray Loudamy Date of Degree: DECEMBER, 2013 Title of Study: CORTÉS AFTER THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO: CONSTRUCTING LEGACY IN NEW SPAIN Major Field: History Abstract: This dissertation examines an important yet woefully understudied aspect of Hernán Cortés after the conquest of Mexico. The Marquisate of the Valley of Oaxaca was carefully constructed during his lifetime to be his lasting legacy in New Spain. The goal of this dissertation is to reexamine published primary sources in light of this new argument and integrate unknown archival material to trace the development of a lasting legacy by Cortés and his direct heirs in Spanish colonial Mexico. Part one looks at Cortés’s life after the conquest of Mexico, giving particular attention to the themes of fame and honor and how these ideas guided his actions. The importance of land and property in and after the conquest is also highlighted. Part two is an examination of the marquisate, discussing the key features of the various landholdings and also their importance to the legacy Cortés sought to construct. -

Mediterranean Action Plan

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN MED POL WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANTS IN MEDITERRANEAN COASTAL CITIES LES STATIONS D’EPURATON DES EAUX USEES MUNICIPALES DANS LES VILLES COTIERES DE LA MEDITERRANEE MAP Technical Reports Series No. 128 UNEP/MAP Athens, 2000 Note: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP/MAP concerning the legal status of any State, Territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries. Responsibility for the preparation of this document was entrusted to WHO (Dr. G. Kamizoulis). Data provided by National MED POL Coordinators have also been included in this report. Note: Les apppellations employées dans ce document et la présentation des données qui y figurent n'impliquent de la part du PNUE/PAM aucune prise de position quant au statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs authorités, ni quant au tracé de leurs frontières ou limites. La responsibilité de l’élaboration de ce document a été confée à l’OMS (Dr. G. Kamizoulis). Des données communiquées par les Coordonnateurs naionaux pur le MED POL on également incluses dans le rapport. © 2001 United Nations Environment Programme / Mediterranean Action Plan (UNEP/MAP) P.O. Box 18019, Athens, Greece © 2001 Programme des Nations Unies pour l'environnement / Plan d’action pur la Méditerranée (PNUE/PAM) B.P. 18019, Athènes, Grèce ISBN 92 807 1963 7 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. -

Evapotranspirations.Pdf

100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 44 Bi z ert e 48 48 E E 47 46 Kelibia N 32 Chet aibi Tabarka 40 Tu ni s - C. 43 46 37 A Collo 36 41 T un is -M. R 35 Annaba El Kala R 46 30 Skikda Beja 40 B. El-Amri E 42 38 Ain El Ksar 41 Ain Draham T 35 33 33 49 I Dellys-Afir 44 Jijel 31 Medjez el bab Nabeul 500 38 AghribCap Sigli 37 39 500 D 45 Bejaïa Guenitra Ben Mehidi E A lger 43 40Tizi Ouzou 42 El Milia Azzaba Jendouba M 43 T henia 40 52 El Harrach 44 Oued Marsa 29 Teboursouk R Ain El Hammam E 5054 Cherchell 40 Ighil 29 Gue l ma 36 M Cap Té nès Ha mi z 28 Bouker dane46 31 38 Hamma Bouziane 22 37 29 Constantine 26 Té nès Blida Bouira 24 Ain Dalia Souk Ahras Le Kef 40 M' Chedellah 28 21 Sil iana 46 39 Mil iana 41 Guenzet 51 57 Br ahim 40 40 El Attafs 34 Me dea 32 Ha mmam G ro uz 25 Monastir 50 28 53 54 Setif Sedrata 50 Cap I vi Ard El Beida Chlef Ghrib Sour El Ghoz lane El Eulma Beni Slimane 52 46 46 B.B.Arreridj 43 Ma t kar Kairouan 400 Merdjet El Amel Berr ouaghia 400 34 35 52 28 51 Mostaga nem 35 29 Boghar Bir Chouhada O um El Bouaghi 5251 Theniet El Had 52 47 47 40 El Nouadeur T hala Tetouan Malaliyene Arzew Relizane Ammi Mo u ss a Sidi Aissa 41 E l Ancor 30 Bou Thaleb 37 Oran 39 33 Kh emisti Chefchaouen 49 Sidi M'hamed 35 Fergoug 46 48 41 33 Tissemsilt Tebessa Ali Tlat 50 47 44 Cheurfas38 37 36 Dahmouni 39 43 Mascara Sidi Bouzid 55 Al-Hoceima Nador Be ni Saf Sar no 38 41 Sidi Ben Adda 34 Ti aret Sfax 34 44 Gh r iss Bakhadda 33 300 38 44 45Ghazaouet Bou Hanifia 300 Zaio Ber k ane 40 Sidi Bel Abbas Dar Dr iouch -

Aicha Heddar, Hamoud Beldjoudi, Christine Authemayou, Roza

ANNALS OF GEOPHYSICS, 59, 2, 2016, S0211; doi:10.4401/ag-6926 Use of the ESI-2007 scale to evaluate the 2003 Boumerdès earthquake (North Algeria) Aicha Heddar1,*, Hamoud Beldjoudi1, Christine Authemayou2, Roza SiBachir1, Abdelkrim Yelles-Chaouche1, Azzedine Boudiaf3 1 Centre de Recherche en Astronomie Astrophysique et Géophysique (CRAAG), Bouzareah-Algiers, Algeria 2 Institut Universitaire Européen de la Mer Technopôle Brest-Iroise, Plouzané, France 3 Consultant Geologist, Sète, France Article history Received November 18, 2015; accepted April 27, 2016. Subject classification: Boumerdès earthquake, Algeria, Earthquake environmental effects, Intensity, ESI-2007 scale, Seismic hazard. ABSTRACT time window for analyzing seismic hazards up to tens of In this study, we applied the environmental seismic intensity (ESI-2007) thousands of years [Michetti et al. 2007, Porfido et al. scale to a major recent Algerian earthquake. The ESI-2007 scale is an ef- 2007]. Thus, progress in the field of earthquake geology fective tool to assess the seismic hazard and has been applied to onshore and paleoseismology where special attention is given to earthquakes. Here we applied the scale to a recent earthquake (Mw 6.8, geological effects [Allen 1975, Audemard and Michetti 2003) that took place offshore in the province of Boumerdès in the north 2011] contributed to the development of the ESI scale in of Algeria along the boundary between African and Eurasian plates. The 2007. One of main results of the INQUA (International main shock was associated to an unknown submarine structure. No sur- Union for Quaternary Research) subcomission group face ruptures were observed on the onshore domain, but many earthquake during the last decade was the implementation of the environmental effects (EEEs) were reported during several field investiga- EEE catalogue and the validation of the ESI scale tions.