Oversight Hearing Committee on Natural Resources U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on the Activities of the Committee on Natural Resources

1 Union Calendar No. 696 114TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 114–886 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES DURING THE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JANUARY 6, 2015–DECEMBER 18, 2015 SECOND SESSION JANUARY 4, 2016–JANUARY 3, 2017 together with SUPPLEMENTAL AND DISSENTING VIEWS DECEMBER 22, 2016.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed VerDate Sep 11 2014 06:35 Jan 06, 2017 Jkt 023127 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6012 Sfmt 6012 E:\HR\OC\HR886.XXX HR886 SSpencer on DSK4SPTVN1PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES VerDate Sep 11 2014 06:35 Jan 06, 2017 Jkt 023127 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 E:\HR\OC\HR886.XXX HR886 SSpencer on DSK4SPTVN1PROD with REPORTS with DSK4SPTVN1PROD on SSpencer 1 Union Calendar No. 696 114TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 114–886 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES DURING THE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JANUARY 6, 2015–DECEMBER 18, 2015 SECOND SESSION JANUARY 4, 2016–JANUARY 3, 2017 together with SUPPLEMENTAL AND DISSENTING VIEWS DECEMBER 22, 2016.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 23–127 WASHINGTON : 2016 VerDate Sep 11 2014 06:35 Jan 06, 2017 Jkt 023127 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR886.XXX HR886 SSpencer on DSK4SPTVN1PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES FULL COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP ROB BISHOP, Utah, Chairman RAU´ L M. -

Newly Elected Representatives in the 114Th Congress

Newly Elected Representatives in the 114th Congress Contents Representative Gary Palmer (Alabama-6) ....................................................................................................... 3 Representative Ruben Gallego (Arizona-7) ...................................................................................................... 4 Representative J. French Hill (Arkansas-2) ...................................................................................................... 5 Representative Bruce Westerman (Arkansas-4) .............................................................................................. 6 Representative Mark DeSaulnier (California-11) ............................................................................................. 7 Representative Steve Knight (California-25) .................................................................................................... 8 Representative Peter Aguilar (California-31) ................................................................................................... 9 Representative Ted Lieu (California-33) ........................................................................................................ 10 Representative Norma Torres (California-35) ................................................................................................ 11 Representative Mimi Walters (California-45) ................................................................................................ 12 Representative Ken Buck (Colorado-4) ......................................................................................................... -

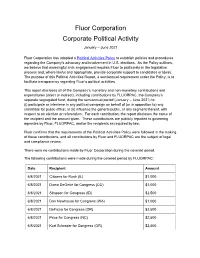

Fluor Political Activities Report: January-June 2021

Fluor Corporation Corporate Political Activity January – June 2021 Fluor Corporation has adopted a Political Activities Policy to establish policies and procedures regarding the Company’s advocacy and involvement in U.S. elections. As the Policy outlines, we believe that meaningful civic engagement requires Fluor to participate in the legislative process and, where lawful and appropriate, provide corporate support to candidates or ideas. The purpose of this Political Activities Report, a semiannual requirement under the Policy, is to facilitate transparency regarding Fluor’s political activities. This report discloses all of the Company’s monetary and non-monetary contributions and expenditures (direct or indirect), including contributions by FLUORPAC, the Company’s separate segregated fund, during the semiannual period (January – June 2021) to: (i) participate or intervene in any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office; or (ii) influence the general public, or any segment thereof, with respect to an election or referendum. For each contribution, the report discloses the name of the recipient and the amount given. These contributions are publicly reported to governing agencies by Fluor, FLUORPAC, and/or the recipients as required by law. Fluor confirms that the requirements of the Political Activities Policy were followed in the making of these contributions, and all contributions by Fluor and FLUORPAC are the subject of legal and compliance review. There were no contributions made by Fluor -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1195 HON. BARBARA LEE HON. ED PERLMUTTER HON. DOUG LAMBORN HON. DEBBIE LESKO

December 21, 2020 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1195 I extend my deepest sympathies to Chief RON WAGONER Joyce lived an extraordinary life by all Spiker’s parents Ron and Jessie, his loving measures. Her husband, Steve, describes her wife of 31 years Anita, and his son Tyler. On HON. ED PERLMUTTER as ‘‘beautiful at many levels, and bordering on behalf of Pennsylvania’s 13th Congressional OF COLORADO being renaissance.’’ Joyce embraced the pop- District, it is an honor to recognize Chief Ron- ular role of being a homemaker to her family, IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ald Spiker’s legacy of service to the John but her efforts and passions didn’t end there. Hyndman community. Monday, December 21, 2020 Joyce returned to college in her 40s and grad- f Mr. PERLMUTTER. Madam Speaker, I rise uated with a degree in social work. Her pas- today to recognize Ron Wagoner with the City sion was always in the well-being of those HONORING THE 65TH ANNIVER- of Lakewood for his long tenure with the City less fortunate. SARY OF THE CHARLES HOUS- and his countless contributions to our commu- Joyce blazed historic trails in her commu- TON BAR ASSOCIATION nity. nity. She co-founded Community Transitions, Ron began work with the City of Lakewood a non-profit organization that served homeless HON. BARBARA LEE on December 28, 1970 and, after 50 years of families, established a volunteer program for OF CALIFORNIA service, plans to retire in January 2021. the District Attorney’s office, and built the DA’s IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Throughout his time with the City, he has had ‘Shape Up’ initiative. -

House Organic Caucus Members

HOUSE ORGANIC CAUCUS The House Organic Caucus is a bipartisan group of Representatives that supports organic farmers, ranchers, processors, distributors, retailers, and consumers. The Caucus informs Members of Congress about organic agriculture policy and opportunities to advance the sector. By joining the Caucus, you can play a pivotal role in rural development while voicing your community’s desires to advance organic agriculture in your district and across the country. WHY JOIN THE CAUCUS? Organic, a $55-billion-per-year industry, is the fastest-growing sector in U.S. agriculture. Growing consumer demand for organic offers a lucrative market for small, medium, and large-scale farms. Organic agriculture creates jobs in rural America. Currently, there are over 28,000 certified organic operations in the U.S. Organic agriculture provides healthy options for consumers. WHAT DOES THE EDUCATE MEMBERS AND THEIR STAFF ON: CAUCUS DO? Keeps Members Organic farming methods What “organic” really means informed about Organic programs at USDA opportunities to Issues facing the growing support organic. organic industry TO JOIN THE HOUSE ORGANIC CAUCUS, CONTACT: Kris Pratt ([email protected]) in Congressman Peter DeFazio’s office Ben Hutterer ([email protected]) in Congressman Ron Kind’s office Travis Martinez ([email protected]) in Congressman Dan Newhouse’s office Janie Costa ([email protected]) in Congressman Rodney Davis’s office Katie Bergh ([email protected]) in Congresswoman Chellie Pingree’s office 4 4 4 N . C a p i t o l S t . N W , S u i t e 4 4 5 A , W a s h i n g t o n D . -

WEDNESDAY, JULY 21, 2021 7:00PM ET VIP Reception | 7:30PM ET Program | Virtual

WEDNESDAY, JULY 21, 2021 7:00PM ET VIP Reception | 7:30PM ET Program | Virtual The Global Down Syndrome Foundation (GLOBAL) is the largest non-profit in the U.S. working to save lives and dramatically improve health outcomes for people with Down syndrome. GLOBAL directly supports over 200 scientists and 2,000 patients with Down syndrome. Working closely with Congress and the National Institutes of Health, GLOBAL is the lead advocacy organization in the U.S. for Down syndrome research and medical care. Given that people with Down syndrome are at extremely high risk for COVID-19 (adults with Down syndrome are four times more likely to be hospitalized and 10 times more likely to develop adverse side effects due to COVID-19) we have decided to hold our 2021 AcceptAbility Gala virtually. GLOBAL’s annual AcceptAbility Gala brings together policymakers from both sides of the aisle, key scientists from NIH, and our Down syndrome community. YOUR support for this inspiring event allows GLOBAL to protect people with Down syndrome from COVID-19; provide world-class care to over 2,000 patients with Down syndrome from 28 states and 10 countries; and fund over 200 scientists working on Down syndrome research with a focus on Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and autoimmune disorders. With support from you and our champions, GLOBAL’s advocacy efforts on Capitol Hill has resulted in a tripling of the NIH Down syndrome research budget, as well as outreach to over 14,000 families. 2021 HONOREES, COMMITTEES & SPECIAL GUESTS Ambassador: Caroline Cardenas Quincy -

Legislative Hearing Committee on Natural Resources U.S

H.R. 445, H.R. 1785, H.R. 4119, H.R. 4901, H.R. 4979, H.R. 5086, S. 311, S. 476, AND S. 609 LEGISLATIVE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PUBLIC LANDS AND ENVIRONMENTAL REGULATION OF THE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION Tuesday, July 29, 2014 Serial No. 113–84 Printed for the use of the Committee on Natural Resources ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov or Committee address: http://naturalresources.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 88–967 PDF WASHINGTON : 2015 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 12:01 Jun 22, 2015 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 J:\04 PUBLIC LANDS & ENV\04JY29 2ND SESS PRINTING\88967.TXT DARLEN COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES DOC HASTINGS, WA, Chairman PETER A. DEFAZIO, OR, Ranking Democratic Member Don Young, AK Eni F. H. Faleomavaega, AS Louie Gohmert, TX Frank Pallone, Jr., NJ Rob Bishop, UT Grace F. Napolitano, CA Doug Lamborn, CO Rush Holt, NJ Robert J. Wittman, VA Rau´ l M. Grijalva, AZ Paul C. Broun, GA Madeleine Z. Bordallo, GU John Fleming, LA Jim Costa, CA Tom McClintock, CA Gregorio Kilili Camacho Sablan, CNMI Glenn Thompson, PA Niki Tsongas, MA Cynthia M. Lummis, WY Pedro R. Pierluisi, PR Dan Benishek, MI Colleen W. -

2012 Election Results Coastal Commission Legislative Report

STATE OF CALIFORNIA—NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY EDMUND G. BROWN, JR., GOVERNOR CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION 45 FREMONT, SUITE 2000 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105- 2219 VOICE (415) 904- 5200 FAX (415) 904- 5400 TDD (415) 597-5885 W-19a LEGISLATIVE REPORT 2012 ELECTION—CALIFORNIA COASTAL DISTRICTS DATE: January 9, 2013 TO: California Coastal Commission and Interested Public Members FROM: Charles Lester, Executive Director Sarah Christie, Legislative Director Michelle Jesperson, Federal Programs Manager RE: 2012 Election Results in Coastal Districts This memo describes the results of the 2012 elections in California’s coastal districts. The November 2012 General Election in California was the first statewide election to feel the full effect of two significant new electoral policies. The first of these, the “Top Two Candidates Open Primary Act,” was approved by voters in 2010 (Proposition 14). Under the new system, all legislative, congressional and constitutional office candidates now appear on the same primary ballot, regardless of party affiliation. The two candidates receiving the most votes in the Primary advance to the General Election, regardless of party affiliation. The June 2012 primary was the first time voters utilized the new system, and the result was numerous intra-party competitions in the November election as described below. The other significant new factor in this election was the newly drawn political districts. The boundaries of legislative and congressional seats were redrawn last year as part of the decennial redistricting process, whereby voting districts are reconfigured based on updated U.S. Census population data. Until 2011, these maps have been redrawn by the majority party in the Legislature, with an emphasis on party registration. -

114Th Congress 285

WASHINGTON 114th Congress 285 Office Listings http://www.herrerabeutler.house.gov 1130 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ........................................... (202) 225–3536 Chief of Staff.—Casey Bowman. FAX: 225–3478 Legislative Director.—Chad Ramey. Legislative Assistants: Jordan Evich, Jessica Wixson. Press Secretary.—Amy Pennington. Executive Assistant / Scheduler.—Terassa Wren. Legislative Correspondent.—Caroline Ehret. Staff Assistant.—Courtney Webb. 750 Anderson Street, Suite B, Vancouver, WA 98661 ............................................................. (360) 695–6292 District Director.—Ryan Hart. Deputy District Director.—Shari Hildreth. Outreach Director.—Pam Peiper. Caseworkers: Ashley Lara, Dale Lewis, Jordan Meade. District Staff Assistant.—Jonathan Egan. Counties: CLARK,COWLITZ,KLICKITAT,LEWIS,PACIFIC,SKAMANIA,THURSTON (part), WAHKIAKUM. Population (2010), 672,448. ZIP Codes: 98304 (part), 98330 (part), 98336, 98355–56, 98361, 98377, 98522, 98527, 98530–33, 98537 (part), 98538– 39, 98542, 98544, 98547 (part), 98554, 98561, 98564–65, 98568 (part), 98570, 98572, 98576 (part), 98577, 98579 (part), 98581–82, 98585–86, 98589 (part), 98590–91, 98593, 98596, 98597 (part), 98601–07, 98609–14, 98616–17, 98619–26, 98628–29, 98631–32, 98635, 98637–45, 98647–51, 98660–66, 98668, 98670–75, 98682–87, 98935 (part), 99322 (part), 99350 (part), 99356 *** FOURTH DISTRICT DAN NEWHOUSE, Republican, of Sunnyside, WA; born in Sunnyside, WA, July 10, 1955; education: graduated, Sunnyside High School, 1973; B.S., Washington -

The National Park Service's

AS DIFFICULT AS POSSIBLE: THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE’S IMPLEMENTATION OF THE GOVERN- MENT SHUTDOWN JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM AND THE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 16, 2013 Serial No. 113–116 (Committee on Oversight and Government Reform) Serial No. 113–48 (Committee on Natural Resources) ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov http://www.house.gov/reform http://naturalresources.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 88–621PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 10:23 Jul 23, 2014 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\88621.TXT APRIL COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM DARRELL E. ISSA, California, Chairman JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland, Ranking MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio Minority Member JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM JORDAN, Ohio Columbia JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts TIM WALBERG, Michigan WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts JUSTIN AMASH, Michigan JIM COOPER, Tennessee PAUL A. GOSAR, Arizona GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania JACKIE SPEIER, California SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee MATTHEW A. CARTWRIGHT, Pennsylvania TREY GOWDY, South Carolina TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas ROBIN L. -

GUIDE to the 117Th CONGRESS

GUIDE TO THE 117th CONGRESS Table of Contents Health Professionals Serving in the 117th Congress ................................................................ 2 Congressional Schedule ......................................................................................................... 3 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) 2021 Federal Holidays ............................................. 4 Senate Balance of Power ....................................................................................................... 5 Senate Leadership ................................................................................................................. 6 Senate Committee Leadership ............................................................................................... 7 Senate Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................. 8 House Balance of Power ...................................................................................................... 11 House Committee Leadership .............................................................................................. 12 House Leadership ................................................................................................................ 13 House Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................ 14 Caucus Leadership and Membership .................................................................................... 18 New Members of the 117th -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E480 HON

E480 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks April 15, 2016 1936, in Budapest, Hungary, and died on his generosity and public service to the citi- leadership the key threat assessments to en- March 16, 2016, at the age of 79. After endur- zens and City of Lewisville. Mr. Carey passed sure safety and security to millions of people ing Nazi occupation and Soviet abuse, he im- away recently at the age of 73 and is survived around the world; and migrated to the United States in 1956. He by his wife of almost 50 years, two children, Whereas, the 21st Space Wing at Peterson earned a degree in chemical engineering at and five grandchildren. Air Force Base in Colorado Springs, Colorado City College of New York (CCNY) and his Mr. Carey and his family moved to provides operational support and infrastructure Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley. Lewisville in 1972. He previously served in the sustainability, and today celebrates the 50th In 1958, Andy Grove married Eva Kastan, a U.S. Army and became an inventory analyst anniversary of the full operational capability of fellow Hungarian refugee. They have two for Halliburton, where he worked for more than Cheyenne Mountain; and daughters, Karen and Robie, whom Andy 38 years. His love for Lewisville inspired him Whereas, the 721st Mission Support Group adored and was fiercely protective of their pri- to commit his time and efforts to ensure the at Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado Springs, vacy. He also leaves eight grandchildren who community’s prosperous growth and the well- Colorado provides the dedicated daily brought him great joy.