Joseph Regenstein Library, University of Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Supplementary Directory of New Bargaining Agents and Contracts in Institutions of Higher Education, 2013-2019

NATIONAL CENTER for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions 2020 Supplementary Directory of New Bargaining Agents and Contracts in Institutions of Higher Education, 2013-2019 William A. Herbert Jacob Apkarian Joseph van der Naald November 2020 NATIONAL CENTER • i • 2020 SUPPLEMENTAL DIRECTORY NATIONAL CENTER for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions 2020 Supplementary Directory of New Bargaining Agents and Contracts in Institutions of Higher Education, 2013-2019 William A. Herbert Jacob Apkarian Joseph van der Naald November 2020 NATIONAL CENTER • ii • 2020 SUPPLEMENTAL DIRECTORY The National Center for the Study of Collective agents, and contracts, with a primary focus on Bargaining in Higher Education and the faculty at institutions of higher education. Professions (National Center) is a labor- management research center at Hunter College, In addition, the National Center organizes City University of New York (CUNY) and an national and regional labor-management affiliated policy research center at the Roosevelt conferences, publishes the peer reviewed House Public Policy Institute. The National Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy, Center’s research and activities focus on research articles for other journals, and collective bargaining, labor relations, and labor distributes a monthly newsletter. The newsletter history in higher education and the professions. resumed in 2014, following a 14-year hiatus. Through the newsletter, we have reported on Since its formation, the National Center has representation petition filings, agency and court functioned as a clearinghouse and forum decisions, the results in representation cases, for those engaged in and studying collective and other developments relating to collective bargaining and labor relations. -

Building Is OPEN Building Is COMPLETE Building Is IN-USE

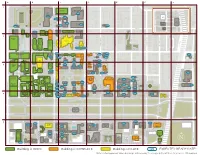

A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S KIMBARK AVE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer Collegium- TBD - Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - TBD - Integrative Science Physics Hitchcock Hall Cobb Zoology Hutchinson Quadrangle - TBD - Gate Club Institute of- PoliticsTBD - Snell -

Fall 2002 What’S New? Page 1

The University of Chicago LIBRARY 1100 East 57th Street Library Reports Chicago, Illinois 60637 and Announcements www.lib.uchicago.edu Volume 7 Number 1 This Issue: Fall 2002 What’s New? page 1 Chalk page 3 Library Society Programs page 4 LIBRA (LIBrary Reports EBSCOhost and Announcements) is Research a newsletter from the Databases page 4 University of Chicago Lewis Carroll, Library, written for the Sylvie and Where are the faculty and University Bruno Concluded. Periodicals? With forty-six community. If you have illustrations by Harry page 5 Furniss (London: questions or comments Macmillan, 1893). Regenstein about this issue of Calendar LIBRA, please contact What's New? Recent Acquisitions in the page 5 Sandra Levy at 773-702-6463 or Crerar Calendar Special Collections Research Center page 6 [email protected] by Alice Schreyer, Director, Special Collections Research Center Contributors: Elisabeth Long Many of the rare book, manuscript and archival mate- Alice Schreyer rials in the Special Collections Research Center that Sem Sutter are used in current research and teaching have been Agnes Tatarka part of the Library's collections since the founding of the University. Perhaps less well known is that each year “new” primary sources are added, part of an ongoing program to develop the resources available in Special Collections through gifts and purchases. This article describes a few recent rare books and manuscripts acquisi- tions. They illustrate approaches to building the collections and the importance of faculty members, alumni and other donors in these continued on page 4 Continued from page 1 ᪾2 What’s New? efforts. -

The Chicago Cluster of Theological Schools

The Chicago Cluster of Theological Schools LIBRARIANS MEETING AGENDA For June 12, 1973 9:30 a.m. BETHANY 1. Approval of May 15 Meeting Minutes and Agenda. 2. Periodicals Project - Where do we go from here? 2.1. BST, CST, LSTC and CTU could reduce some duplicate subsctiptions and bindings by mutual agreement, 2.2. BST, LSTC, CTS could start to "tool-up" for the periodicals center during academic year 1973-74 and hope that CTU would join. 2.3. Proposed study of use of Cluster periodicals should be undertaken. Should this be done at all Cluster libraries, at selected Cluster libraries? 2.4. Other suggestions or alternatives. 3. Appointment of Committee for definitions related to cataloguing, classi fication and technical services. (Members to be announced). 4. Approval of Due Dates for 1973-74. 5. Other Business. Bellarmine School of Theology — Bethany Theological Seminary — Catholic Theological Union Chicago Theological Seminary — DeAndreis Seminary — Meadville Theological School Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago — Northern Baptist Theological Seminary The Chicago Cluster of Theological Schools MEMORANDUM DATE: September 21, 1973 •0* Cluster Librarians FROM: Office of CCTS Library Coordinator - Al Hurd SUBJECT: CCTS Librarians meeting; Friday, September 28, 1973, at LSTC (Jesuit School of Theology is the host) beginning with lunch at the LSTC cafeteria. The Cluster will host the librarians for lunch. We will probably have a special area or tables in the LSTC cafeteria where we can share lunch together. After lunch we will hold our meeting in the second floor Con ference room near the LSTC library. I am afraid that we have lost sight of many plans over the long summer months so I would like to spend time at this meeting reviewing where we are and what we will be doing during academic year 73/74. -

Religion and Reform in the City: the Re-Thinking Chicago Movement of the 1930S

Wright State University CORE Scholar History Faculty Publications History 1986 Religion and Reform in the City: The Re-Thinking Chicago Movement of the 1930s Jacob Dorn Wright State University - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/history Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Dorn, J. (1986). Religion and Reform in the City: The Re-Thinking Chicago Movement of the 1930s. Church History, 55 (3), 323-337. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/history/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Religion and Reform in the City: The Re-Thinking Chicago Movement of the 1930s JACOB H. DORN Historians have produced a rich and sophisticated literature on urban reform in the progressive era before the First World War. It includes numerous studies of individual cities, biographies of urban leaders, and analyses of particular movements and organizations. This literature illu- minates important variations among reformers and their achievements, the relationships between urban growth and reform, and the functional role of the old-style political machines against which progressives battled. Similarly, there are many examinations of progressive-era reformers' ideas about and attitudes toward the burgeoning industrial cities that had come into being with disquieting rapidity during their own lifetimes. Some of these works go well beyond the controversial conclusions of Morton and Lucia White in The Intellectual Versus the City (1964) to find more complex-and sometimes more positive-assessments of the new urban civilization.' Substantially less is known about efforts to reform particular cities and about the ideas and attitudes of urban intellectuals in the interwar years, especially the 1930s. -

Self-Guided Tours

ALL THINGS visit.uchicago.edu IF YOU HAVE 4 HOURS self-guided BOTANY POND 57th St. (west of Hutchinson Court) Located in the middle of campus, Botany Pond is the university’s tours biodiversity hotspot, hosting a remarkable variety of animals including ducks, four species of turtles, and a dozen species of dragonflies. For over a century, the pond has served as a tranquil IF YOU HAVE 1 HOUR outdoor study space, relaxation destination, and nexus of intel- lectual life on campus. Plus, rumor has it, if a couple kisses on the MAIN QUAD bridge over Botany Pond, they will get married. 57th St. – 59th St. Between University Ave. and Ellis Ave. architecture.uchicago.edu ROCKEFELLER MEMORIAL CHAPEL 5850 S. Woodlawn Ave. (at E. 59th St.) The centerpiece of the University of Chicago campus rockefeller.uchicago.edu/events is without question its main quadrangle. Designed in 1891 by famed Chicago architect Henry Ives Cobb, Rockefeller Memorial Chapel is a hub for ceremonies, the Neo-Gothic style of the Quad lends itself to theater, orchestral performances, chorus groups, classrooms, laboratories, and libraries alike. At vari- concerts, and even circus acts. While you’re there, ous points in the year, the Main Quad is the site of make sure to walk up the 271 steps to the top for 360 everything from quiet study and relaxation to the degree views of Chicago, Lake Michigan, northern bustling Spring Convocation ceremony. Indiana and the port, the Michigan shoreline, and of course, the University itself. Visit the Rockefeller Memorial Chapel website for information on daily Car- HARPER MEMORIAL LIBRARY READING ROOM illon tours, nondenominational religious services, and 1116 E. -

Library Director and University Librarian

LIBRARY DIRECTOR AND UNIVERSITY LIBRARIAN The University of Chicago invites applications and nominations for the position of Library Director and University Librarian. Reporting to the Provost, the Library Director is a critical partner in, and facilitator of, the rigorous intellectual engagement that characterizes the University of Chicago. The new Library Director will have a tremendous opportunity to work across the entire university, building upon the Library’s exceptional service-oriented culture in order to further the rigorous academic goals of the University. Working with a team of approximately 200 talented and dedicated library staff, the new Library Director will lead the process of developing and implementing a comprehensive strategic vision for the future of the Library, in terms of both its role within the University ecosystem and its relationship to the fast-changing world of information management. The new Library Director will be an experienced and effective leader who will be a champion for the centrality of the library in an academic research university. The new Library Director should bring a creative, intellectual, and collaborative spirit to the challenge of making a library that is already well respected and beloved for the depth of its collections and prominence both on- and off-campus even more central to the University of Chicago’s mission and even more recognized around the nation and world. The Joseph Regenstein Library University of Chicago, Library Director and University Librarian Page 2 ABOUT THE UNIVERSITY The University of Chicago is a research university in a dynamic urban setting that has driven new ways of thinking since 1890. -

Curriculumvit Æ

C U R R I C U L U M V I T Æ Richard W. Clement wk. 277-2678; Fax 277-7196 [email protected] EDUCATION 1984-85 A.M., Graduate Library School, University of Chicago. Paper: “Two Contemporary Editions of Pope Gregory the Great’s Liber regulae pastoralis in Troyes MS 504.” 1981 Diploma in TESL, Royal Society of Arts (England). 1978-81 Research Student, University of Cambridge. 1978 Certificate in Danish, University of Copenhagen. 1975-77 M.A., English, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Thesis: “An Analysis of Non-Finite Verb Forms as an Indication of the Style of Translation in the Old English Version of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History.” 1973-75 B.A., History, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. 1969-71 University of Wisconsin, Madison. EMPLOYMENT Dean and Professor, College of University Libraries & Learning Sciences, University of New Mexico, 2014-. Dean of Libraries, Utah State University, 2008-2014. Adjunct Professor of History, Utah State University, 2008-. Special Collections Librarian (head of the Department of Special Collections), Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas, 2000-2008 (Assistant Special Collections Librarian, 1986-1991; Associate Special Collections Librarian [tenured], 1991-2000). Bibliographer for English and American Language and Literature, University of Kansas, 2005-2008. Courtesy Professor and member of the Graduate Faculty, Department of English, University of Kansas, 2004- (Courtesy Assistant Professor of English, 1986-1991; Associate, 1991-2004). Visiting Lecturer, School of Library and Information Management, Emporia State University, 1988. Visiting Professor, Graduate School of Library Service, University of Alabama, July-August, 1986. Lead Rare Book Cataloger, Joseph Regenstein Library, University of Chicago, 1985-1986. -

Sustainability Plan Update

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Sustainability Plan AREA 1 Update Climate Change and Energy AREA 2 High Performance Buildings December 2019 AREA 3 Multi-Modal Transportation AREA 4 Waste Reduction AREA 5 Food Systems AREA 6 Green Space AREA 7 Water Conservation AREA 8 Environmentally Preferable Procurement AREA 9 Building Awareness and Partnerships EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sustainability at the University of Chicago The University of Chicago is committed to creating a sustainable campus. With its tradition of rigorous inquiry, the University is positioned to evaluate the challenges of sustainability and create measurable results. UChicago students’ Green Campus Initiative launches The Office of the Provost forms The Office of Sustainability establishes the the University’s first official UChicago departments the Office of Sustainability Water Use Profile and releases the Greenhouse Sustainability Council. increase sustainability focus. Advisory Council (OSAC). Gas Emissions Reduction Plan. 2004 2006–2012 2015 2018 1990–2004 2008 2013 2016 2019 The University has an informal The University establishes the The Board of The Office of Sustainability The Energy Management sustainability council. Office of Sustainability. Trustees supports the provides its first Baseline Information System Sustainability Plan. Report (Sustainability is implemented. Plan) and the University’s first annual Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory. 2/13 The University of Chicago | Sustainability Plan Update 2019 sustainability.uchicago.edu CLIMATE CHANGE HIGH PERFORMANCE BUILDINGS -

1 Concrete Poetry/Concrete Books: Artists' Books in German-Speaking

Concrete Poetry/Concrete Books: Artists’ Books in German-Speaking Space after 1945 Curated by Caroline Lillian Schopp, PhD candidate in art history Item Checklist What is an Artist's Book? N7433.4.R68Q5 1965 Dieter Roth (1930-1998), Swiss-German Quick Reykjavik:́ Verlag D. Roth, 1965/1994. Rare Book Collection Alison Knowles (1933-), American By Alison Knowles New York: Something Else Press, 1966 Great Bear Pamphlet On loan from The Collection of Hannah B. Higgins and Joseph B. Reinstein PN3222.V5W4 VALIE EXPORT (1940-), Austrian Peter Weibel (1944-), Austrian wien: bildkompendium wiener aktionismus und film [vienna: image-compendium of viennese actionism and film] Frankfurt: Kohlkunstverlag, 1970 Rare Book Collection NK3631.S8 A78 1963 Thomas Bayrle (1937-), German Bernhard Jäger (1935-), German V. O. Stomps (1897-1970), German Artistisches ABC [Artistic ABC] Frankfurt am Main: Typos-Verlag, 1963. Rare Book Collection KP Brehmer (1938-1997), German Braunwerte [Brown-Values] Köln: art intermedia, 1971 Private Collection f PT2611.A22P67 1970 Peter Faecke (1940-2014), German Wolf Vostell (1932-1998), German Postversand, Roman. Spiel ohne Grenzen [Mailing, Novel. Game without Boundaries] Neuwied: Luchterhand, 1970-1973 Rare Book Collection f N6888.V66A4 1970 Wolf Vostell (1932-1998), German Ruhender Verkehr: Aktionsplastik auf der Strasse vor der Galerie art intermedia [Stationary Traffic: Action-Sculpture on the Street in front of Gallery art intermedia] Köln: art intermedia, 1970 Rare Book Collection Warja Lavater (1913-2007), Swiss Cendrillon [Cinderella] Paris: Maegt Editeur, 1976 Wool Collection 1 Dieter Roth (1930-1998), Swiss-German Bok AB [Book AB] Cologne: D. Roth, 1973, 2nd ed. Wool Collection ff N6888.V66 V672 1971 Wolf Vostell (1932-1998), German Betonbuch [Concrete Book] Hinwil, Switzerland: Edition Howeg, 1971 Rare Book Collection Concrete Poetry, Action Poetry, Chocolate Poetry Dieter Roth (1930-1998), Swiss-German Poetrie. -

Integrating the Life of the Mind, Danielle Allen

Integrating the Life of the Mind Item Captions, Danielle Allen Case 1: The Myth of Openness 1. In the U.S. Circuit Court, N. District of Illinois, The Union Mutual Life Insurance Co. vs. The University of Chicago. p. 172 Old University of Chicago Records. This document records the testimony of University of Chicago President Galusha Anderson in the 1884 foreclosure proceedings against the old University. 2. Photograph of Galusha Anderson, [n.d.]. Archival Photographic Files. Anderson was born in 1832 and trained at Rochester Theological Seminary. He served as pastor of Second Baptist Church in St. Louis from 1858-1866 and of Second Baptist in Chicago from 1876 to 1878 when he became fifth president of the University of Chicago. He left the old University when it closed in 1886 but in 1892 returned to the new University as professor in the Divinity School, from which he retired in 1904. He died in 1918. 3. Galusha Anderson. The Story of a Border City during the Civil War. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1908. Rare Book Collection, Gift of Danielle Allen. In retirement, Anderson wrote this memoir of his time as pastor of Second Baptist in St. Louis during the Civil War. He had worked aggressively to keep Missouri in the Union and devoted considerable energy to the establishment of “negro schools” throughout the city. 4. Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, South Carolina. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1872. Vol. 3. General Collections. The Old University of Chicago was struggling to find its feet in the same years that the country was struggling with the consequences of the Civil War. -

Samuel King Allison Biographical Memoir

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES S A M U E L K IN G A LLISON 1900—1965 A Biographical Memoir by RO GER H. HILDEBRAND Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1999 NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS WASHINGTON D.C. Courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory SAMUEL KING ALLISON November 13, 1900–September 15, 1965 BY ROGER H. HILDEBRAND AMUEL K. ALLISON began his professional life at a time of Sintense interest in the properties and interactions of X rays. His contributions to the field were immediately recog- nized by the scientific community and especially by A. H. Compton, who was responsible for bringing him back to his alma mater, the University of Chicago. It was also near the time when Cockroft-Walton accelerators and then Van de Graaff machines began producing beams of protons and deuterons. His contributions to nuclear and atomic phys- ics, using these accelerators, were well recognized during his lifetime, but they have grown in significance with the emergence of new fields, especially nuclear astrophysics. FAMILY AND EARLY YEARS Allison always regarded himself as a product of the Uni- versity of Chicago and its surrounding community, Hyde Park. He attended the John Fiske Grammar School and Hyde Park High School. His father Samuel Buell Allison was the principal of an elementary school in the Chicago Public School System. The family owned one of the first automobiles in the neighborhood. When school was out they would drive with their friends to the family summer home near Three Lakes, Wisconsin.