Probing the Dark Matter Content of Local Group Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies with FLAMES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

![Arxiv:2105.11583V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 2 Jul 2021 Keck-HIRES, APF-Levy, and Lick-Hamilton Spectrographs](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4203/arxiv-2105-11583v2-astro-ph-ep-2-jul-2021-keck-hires-apf-levy-and-lick-hamilton-spectrographs-364203.webp)

Arxiv:2105.11583V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 2 Jul 2021 Keck-HIRES, APF-Levy, and Lick-Hamilton Spectrographs

Draft version July 6, 2021 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX63 The California Legacy Survey I. A Catalog of 178 Planets from Precision Radial Velocity Monitoring of 719 Nearby Stars over Three Decades Lee J. Rosenthal,1 Benjamin J. Fulton,1, 2 Lea A. Hirsch,3 Howard T. Isaacson,4 Andrew W. Howard,1 Cayla M. Dedrick,5, 6 Ilya A. Sherstyuk,1 Sarah C. Blunt,1, 7 Erik A. Petigura,8 Heather A. Knutson,9 Aida Behmard,9, 7 Ashley Chontos,10, 7 Justin R. Crepp,11 Ian J. M. Crossfield,12 Paul A. Dalba,13, 14 Debra A. Fischer,15 Gregory W. Henry,16 Stephen R. Kane,13 Molly Kosiarek,17, 7 Geoffrey W. Marcy,1, 7 Ryan A. Rubenzahl,1, 7 Lauren M. Weiss,10 and Jason T. Wright18, 19, 20 1Cahill Center for Astronomy & Astrophysics, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 2IPAC-NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 4Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 5Cahill Center for Astronomy & Astrophysics, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 6Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, The Pennsylvania State University, 525 Davey Lab, University Park, PA 16802, USA 7NSF Graduate Research Fellow 8Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA 9Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 10Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai`i, -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Astrophysics in 2006 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5760h9v8 Journal Space Science Reviews, 132(1) ISSN 0038-6308 Authors Trimble, V Aschwanden, MJ Hansen, CJ Publication Date 2007-09-01 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9224-0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Space Sci Rev (2007) 132: 1–182 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9224-0 Astrophysics in 2006 Virginia Trimble · Markus J. Aschwanden · Carl J. Hansen Received: 11 May 2007 / Accepted: 24 May 2007 / Published online: 23 October 2007 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007 Abstract The fastest pulsar and the slowest nova; the oldest galaxies and the youngest stars; the weirdest life forms and the commonest dwarfs; the highest energy particles and the lowest energy photons. These were some of the extremes of Astrophysics 2006. We attempt also to bring you updates on things of which there is currently only one (habitable planets, the Sun, and the Universe) and others of which there are always many, like meteors and molecules, black holes and binaries. Keywords Cosmology: general · Galaxies: general · ISM: general · Stars: general · Sun: general · Planets and satellites: general · Astrobiology · Star clusters · Binary stars · Clusters of galaxies · Gamma-ray bursts · Milky Way · Earth · Active galaxies · Supernovae 1 Introduction Astrophysics in 2006 modifies a long tradition by moving to a new journal, which you hold in your (real or virtual) hands. The fifteen previous articles in the series are referenced oc- casionally as Ap91 to Ap05 below and appeared in volumes 104–118 of Publications of V. -

Today in Astronomy 106: Exoplanets

Today in Astronomy 106: exoplanets The successful search for extrasolar planets Prospects for determining the fraction of stars with planets, and the number of habitable planets per planetary system (fp and ne). T. Pyle, SSC/JPL/Caltech/NASA. 26 May 2011 Astronomy 106, Summer 2011 1 Observing exoplanets Stars are vastly brighter and more massive than planets, and most stars are far enough away that the planets are lost in the glare. So astronomers have had to be more clever and employ the motion of the orbiting planet. The methods they use (exoplanets detected thereby): Astrometry (0): tiny wobble in star’s motion across the sky. Radial velocity (399): tiny wobble in star’s motion along the line of sight by Doppler shift. Timing (9): tiny delay or advance in arrival of pulses from regularly-pulsating stars. Gravitational microlensing (10): brightening of very distant star as it passes behind a planet. 26 May 2011 Astronomy 106, Summer 2011 2 Observing exoplanets (continued) Transits (69): periodic eclipsing of star by planet, or vice versa. Very small effect, about like that of a bug flying in front of the headlight of a car 10 miles away. Imaging (11 but 6 are most likely to be faint stars): taking a picture of the planet, usually by blotting out the star. Of these by far the most useful so far has been the combination of radial-velocity and transit detection. Astrometry and gravitational microlensing of sufficient precision to detect lots of planets would need dedicated, specialized observatories in space. Imaging lots of planets will require 30-meter-diameter telescopes for visible and infrared wavelengths. -

19 6 6Apj. . .14 6. .743D the VARIABILITY of RHO PUPPIS* I. J

.743D 6. .14 THE VARIABILITY OF RHO PUPPIS* . I. J. Danziger and L. V. Kumf 6ApJ. Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories 6 19 Carnegie Institution of Washington, California Institute of Technology Received April 30, 1966 ABSTRACT The results of simultaneous spectrophotometric and spectral observations of the short-period variable star, p Puppis, are reported. The amplitudes of radial-velocity, light, and temperature variations are 11 km/sec, 0.15 mag., and 280° K, respectively. The relative phases differ from those observed in cluster- type c variables. Estimates of the absolute luminosity and mass from the observed gravity and the Py/(p/po) — Q relationship indicate that either p Puppis is pulsating in a higher-order harmonic mode than the first or the theory of its pulsation is not understood. I. INTRODUCTION The bright star p Puppis, classified in the MKK system as type F6II, was first shown to be variable in light (period 0.141 days) by Eggen (1956) who measured a total ampli- tude of 0.15 mag. Struve, Sahade, and Zebergs (1956) showed that there is an associated variation in radial velocity with a total amplitude of 10 km/sec and that maximum brightness occurs approximately 0.02 days later than minimum radial velocity. Bappu (1959) reported that two-color measurements indicate a variation in temperature of 300° K. An intrinsic luminosity of p Puppis, MPg = +2.4, was obtained by Kinman (1959). He assumed it fitted the observed period-luminosity relation of cluster-type c variables in order to use an observed period-luminosity relation. Strömgren’s c-l sys- tem indices were measured by McNamara and Augason (1962) to derive Mpg = +1.7 and a mass 9J£ = 3.2 $)îo from the period-density law with the pulsation constant Q ~ 0-041* It is of interest to note that, although p Puppis has been classified as a ô Scuti star, none of the multiple-period characteristics associated with such stars has been found to apply to it. -

Ghost Imaging of Space Objects

Ghost Imaging of Space Objects Dmitry V. Strekalov, Baris I. Erkmen, Igor Kulikov, and Nan Yu Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, California 91109-8099 USA NIAC Final Report September 2014 Contents I. The proposed research 1 A. Origins and motivation of this research 1 B. Proposed approach in a nutshell 3 C. Proposed approach in the context of modern astronomy 7 D. Perceived benefits and perspectives 12 II. Phase I goals and accomplishments 18 A. Introducing the theoretical model 19 B. A Gaussian absorber 28 C. Unbalanced arms configuration 32 D. Phase I summary 34 III. Phase II goals and accomplishments 37 A. Advanced theoretical analysis 38 B. On observability of a shadow gradient 47 C. Signal-to-noise ratio 49 D. From detection to imaging 59 E. Experimental demonstration 72 F. On observation of phase objects 86 IV. Dissemination and outreach 90 V. Conclusion 92 References 95 1 I. THE PROPOSED RESEARCH The NIAC Ghost Imaging of Space Objects research program has been carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech. The program consisted of Phase I (October 2011 to September 2012) and Phase II (October 2012 to September 2014). The research team consisted of Drs. Dmitry Strekalov (PI), Baris Erkmen, Igor Kulikov and Nan Yu. The team members acknowledge stimulating discussions with Drs. Leonidas Moustakas, Andrew Shapiro-Scharlotta, Victor Vilnrotter, Michael Werner and Paul Goldsmith of JPL; Maria Chekhova and Timur Iskhakov of Max Plank Institute for Physics of Light, Erlangen; Paul Nu˜nez of Coll`ege de France & Observatoire de la Cˆote d’Azur; and technical support from Victor White and Pierre Echternach of JPL. -

Exoplanet Community Report

JPL Publication 09‐3 Exoplanet Community Report Edited by: P. R. Lawson, W. A. Traub and S. C. Unwin National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California March 2009 The work described in this publication was performed at a number of organizations, including the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Publication was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Compiling and publication support was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology under a contract with NASA. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement by the United States Government, or the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. © 2009. All rights reserved. The exoplanet community’s top priority is that a line of probeclass missions for exoplanets be established, leading to a flagship mission at the earliest opportunity. iii Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................1 1.2 EXOPLANET FORUM 2008: THE PROCESS OF CONSENSUS BEGINS.....................................................2 -

Astrophysical Studies of Extrasolar Planetary Systems Using Infrared Interferometric Techniques Olivier Absil

Astrophysical studies of extrasolar planetary systems using infrared interferometric techniques Olivier Absil To cite this version: Olivier Absil. Astrophysical studies of extrasolar planetary systems using infrared interferometric techniques. Astrophysics [astro-ph]. Université de Liège, 2006. English. tel-00124720 HAL Id: tel-00124720 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00124720 Submitted on 15 Jan 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Facult´edes Sciences D´epartement d’Astrophysique, G´eophysique et Oc´eanographie Astrophysical studies of extrasolar planetary systems using infrared interferometric techniques THESE` pr´esent´eepour l’obtention du diplˆomede Docteur en Sciences par Olivier Absil Soutenue publiquement le 17 mars 2006 devant le Jury compos´ede : Pr´esident: Pr. Jean-Pierre Swings Directeur de th`ese: Pr. Jean Surdej Examinateurs : Dr. Vincent Coude´ du Foresto Dr. Philippe Gondoin Pr. Jacques Henrard Pr. Claude Jamar Dr. Fabien Malbet Institut d’Astrophysique et de G´eophysique de Li`ege Mis en page avec la classe thloria. i Acknowledgments First and foremost, I want to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Jean Surdej. I am forever indebted to him for striking my interest in interferometry back in my undergraduate student years; for introducing me to the world of scientific research and fostering so many international collaborations; for helping me put this work in perspective when I needed it most; and for guiding my steps, from the supervision of diploma thesis to the conclusion of my PhD studies. -

Astrophysics in 2006 3

ASTROPHYSICS IN 2006 Virginia Trimble1, Markus J. Aschwanden2, and Carl J. Hansen3 1 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-4575, Las Cumbres Observatory, Santa Barbara, CA: ([email protected]) 2 Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory, Organization ADBS, Building 252, 3251 Hanover Street, Palo Alto, CA 94304: ([email protected]) 3 JILA, Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder CO 80309: ([email protected]) Received ... : accepted ... Abstract. The fastest pulsar and the slowest nova; the oldest galaxies and the youngest stars; the weirdest life forms and the commonest dwarfs; the highest energy particles and the lowest energy photons. These were some of the extremes of Astrophysics 2006. We attempt also to bring you updates on things of which there is currently only one (habitable planets, the Sun, and the universe) and others of which there are always many, like meteors and molecules, black holes and binaries. Keywords: cosmology: general, galaxies: general, ISM: general, stars: general, Sun: gen- eral, planets and satellites: general, astrobiology CONTENTS 1. Introduction 6 1.1 Up 6 1.2 Down 9 1.3 Around 10 2. Solar Physics 12 2.1 The solar interior 12 2.1.1 From neutrinos to neutralinos 12 2.1.2 Global helioseismology 12 2.1.3 Local helioseismology 12 2.1.4 Tachocline structure 13 arXiv:0705.1730v1 [astro-ph] 11 May 2007 2.1.5 Dynamo models 14 2.2 Photosphere 15 2.2.1 Solar radius and rotation 15 2.2.2 Distribution of magnetic fields 15 2.2.3 Magnetic flux emergence rate 15 2.2.4 Photospheric motion of magnetic fields 16 2.2.5 Faculae production 16 2.2.6 The photospheric boundary of magnetic fields 17 2.2.7 Flare prediction from photospheric fields 17 c 2008 Springer Science + Business Media. -

A Three-Planet Extrasolar System

quires that common properties in all the Acknowledgements Koch A. et al. 2006a, The Messenger 123, 38 dSphs be identified – we must therefore Koch A. et al. 2006b, AJ 131, 895 Mark I. Wilkinson acknowledges the Particle Physics Majewski S. R. et al. 2005, AJ 130, 2677 carry out similar studies of all dSphs. and Astronomy Research Council of the United Martin N. et al. 2006, MNRAS 367, L69 Kingdom for financial support. Andreas Koch and Mateo M. et al. 1993, AJ 105, 510 Finally, in the area of dynamical model- Eva K. Grebel thank the Swiss National Science Mateo M. 1997, ASP Conf. Ser. 116, 259 ling, identifying correlations between the Foundation for financial support. Mateo M. et al. 1998, AJ 116, 2315 Monelli M. et al. 2003, AJ 126, 218 kinematics and abundances of the stel- Munoz R. R. et al. 2005, ApJ 631, L137 lar populations in dSphs (e.g. Tolstoy et References Shetrone M. D. et al. 2001, ApJ 548, 592 al. 2006) is likely to provide important Tolstoy E. et al. 2006, The Messenger 123, 33 new information about the formation and Aaronson M. 1983, ApJ 266, L11 Wilkinson M. I. et al. 2002, MNRAS 330, 778 Belokurov V. et al. 2006, ApJL, submitted, Wilkinson M. I. et al. 2004, MNRAS 611, L21 evolution of these objects, which in turn astro-ph/0604355 Wilkinson M. I. et al. 2006, in proceedings of XXIst will further constrain models of any astro- Goerdt T. et al. 2006, MNNRAS 368, 1073 IAP meeting, EDP sciences, astro-ph/0602186 physical feedback on their dark matter. -

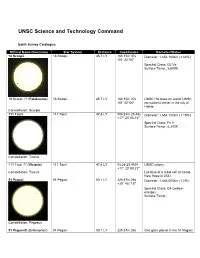

UNSC Science and Technology Command

UNSC Science and Technology Command Earth Survey Catalogue: Official Name/(Common) Star System Distance Coordinates Remarks/Status 18 Scorpii {TCP:p351} 18 Scorpii {Fact} 45.7 LY 16h 15m 37s Diameter: 1,654,100km (1.02R*) {Fact} -08° 22' 06" {Fact} Spectral Class: G2 Va {Fact} Surface Temp.: 5,800K {Fact} 18 Scorpii ?? (Falaknuma) 18 Scorpii {Fact} 45.7 LY 16h 15m 37s UNSC HQ base on world. UNSC {TCP:p351} {Fact} -08° 22' 06" recruitment center in the city of Halkia. {TCP:p355} Constellation: Scorpio 111 Tauri 111 Tauri {Fact} 47.8 LY 05h:24m:25.46s Diameter: 1,654,100km (1.19R*) {Fact} +17° 23' 00.72" {Fact} Spectral Class: F8 V {Fact} Surface Temp.: 6,200K {Fact} Constellation: Taurus 111 Tauri ?? (Victoria) 111 Tauri {Fact} 47.8 LY 05:24:25.4634 UNSC colony. {GoO:p31} {Fact} +17° 23' 00.72" Constellation: Taurus Location of a rebel cell at Camp New Hope in 2531. {GoO:p31} 51 Pegasi {Fact} 51 Pegasi {Fact} 50.1 LY 22h:57m:28s Diameter: 1,668,000km (1.2R*) {Fact} +20° 46' 7.8" {Fact} Spectral Class: G4 (yellow- orange) {Fact} Surface Temp.: Constellation: Pegasus 51 Pegasi-B (Bellerophon) 51 Pegasi 50.1 LY 22h:57m:28s Gas giant planet in the 51 Pegasi {Fact} +20° 46' 7.8" system informally named Bellerophon. Diameter: 196,000km. {Fact} Located on the edge of UNSC territory. {GoO:p15} Its moon, Pegasi Delta, contained a Covenant deuterium/tritium refinery destroyed by covert UNSC forces in 2545. {GoO:p13} Constellation: Pegasus 51 Pegasi-B-1 (Pegasi 51 Pegasi 50.1 LY 22h:57m:28s Moon of the gas giant planet 51 Delta) {GoO:p13} +20° 46' 7.8" Pegasi-B in the 51 Pegasi star Constellation: Pegasus system; a Covenant stronghold on the edge of UNSC territory. -

2005 Astronomy Magazine Index

2005 Astronomy Magazine Index Subject index flyby of Titan, 2:72–77 Einstein, Albert, 2:30–53 Cassiopeia (constellation), 11:20 See also relativity, theory of Numbers Cassiopeia A (supernova), stellar handwritten manuscript found, 3C 58 (star remnant), pulsar in, 3:24 remains inside, 9:22 12:26 3-inch telescopes, 12:84–89 Cat's Eye Nebula, dying star in, 1:24 Einstein rings, 11:27 87 Sylvia (asteroid), two moons of, Celestron's ExploraScope telescope, Elysium Planitia (on Mars), 5:30 12:33 2:92–94 Enceladus (Saturn's moon), 11:32 2003 UB313, 10:27, 11:68–69 Cepheid luminosities, 1:72 atmosphere of water vapor, 6:22 2004, review of, 1:31–40 Chasma Boreale (on Mars), 7:28 Cassini flyby, 7:62–65, 10:32 25143 (asteroid), 11:27 chonrites, and gamma-ray bursts, 5:30 Eros (asteroid), 11:28 coins, celestial images on, 3:72–73 Eso Chasma (on Mars), 7:28 color filters, 6:67 Espenak, Fred, 2:86–89 A Comet Hale-Bopp, 7:76–79 extrasolar comets, 9:30 Aeolis (on Mars), 3:28 comets extrasolar planets Alba Patera (Martian volcano), 2:28 from beyond solar system, 12:82 first image of, 4:20, 8:26 Aldrin, Buzz, 5:40–45 dust trails of, 12:72–73 first light from, who captured, 7:30 Altair (star), 9:20 evolution of, 9:46–51 newly discovered low-mass planets, Amalthea (Jupiter's moon), 9:28 extrasolar, 9:30 1:68–71 amateur telescopes. See telescopes, Conselice, Christopher, 1:20 smallest, 9:26 amateur constellations whether have diamond layers, 5:26 Andromeda Galaxy (M31), 10:84–89 See also names of specific extraterrestrial life, 4:28–34 disk of stars surrounding, 7:28 constellations eyepieces, telescope.