Implementation of the Uttarakhand Tobacco Free Initiative in Schools, India, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tobacco – a Threat to Development”

photo : Chris Stowers/PANOS Tobacco is extraordinarily dangerous to human The vector of the tobacco epidemic is a wealthy, health and highly damaging to national economies. powerful, transnational industry. Nearly 1 billion people in the world smoke every day; about 80 From 1970 to 2000, cigarette consumption tripled in developing percent of them are in low- and middle-income countries countries3 due to aggressive acquisition and marketing (LMICs).1 strategies. Over 6 million people die from tobacco use every year, the Tobacco industry revenue dwarfs the GDP of many countries. majority in their most productive years (30-69 years of age).2 Manufacturers' worldwide profits were about US$50 billion in 2012.4 The industry uses its wealth to battle for market share in 5 Over-burdened health systems in all countries are the developing world. already caring for countless people who have been disabled by cancer, stroke, emphysema and the We know exactly how to tackle the scourge of myriad other non-communicable diseases (NCDs) tobacco. caused by tobacco. We have an internationally negotiated, legally binding package of evidence-based tobacco control measures, the WHO Tobacco-related illnesses and premature mortality impose 6 high productivity costs on economies because of sick workers Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the first modern- and those who die prematurely during their working years. day public health treaty. Parties to the FCTC include 179 Lost economic opportunities in highly-populated developing countries and the European Union. Unfortunately, the slow countries will be particularly severe as tobacco use is high pace of FCTC implementation costs countless lives and and growing in those areas. -

Communications Officer Philippines 2014

Communications Officer, The Philippines World Lung Foundation was established in response to the global epidemic of lung disease, which kills 10 million people each year. The organization also works on maternal and infant mortality reduction initiatives. WLF improves global health by improving local health capacity, by supporting operational research, by developing public policy and by delivering public education. The organization’s areas of emphasis are tobacco control, maternal and infant mortality prevention, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, asthma, and child lung health. worldlungfoundation.org. WLF is also one of five coordinating partners of the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use in low- and middle-income countries, where more than two-thirds of the world’s smokers live. WLF supports mass media communication efforts in several priority countries including, but not limited to: China, India, Russia, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Mexico, Egypt, Pakistan, Poland, Brazil, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Turkey and Ukraine. World Lung Foundation is seeking a Communications Officer based in Manila, Philippines to provide technical assistance to governments and non-governmental organizations on communication strategies and to implement WLF communication initiatives. The Communications Officer will work flexibly up to 16 hours a week (two days a week equivalent) to represent WLF and provide on-the-ground management of its projects and priorities. The Communications Officer will report to WLF headquarters in New York. Travel within the Philippines, -

Union BI Commitment Press Statement

Contact: Dr. Ehsan Latif Director, Tobacco Control Department +44 (0)7792111273 The Union welcomes Bloomberg Philanthropies’ renewed commitment to global tobacco control 22 March 2012, Paris/Singapore – Philanthropist and New York City Mayor Michel R. Bloomberg announced today an additional commitment of US $220 million to the global fight against tobacco use. The announcement, which came at the World Conference on Tobacco or Health in Singapore, will extend funding for the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use (BI) for four more years. The funds allocated will continue to support tobacco control efforts in low- and middle-income countries where 80% of the world’s smokers live. Since the initiative began in 2006, effective tobacco control policies have been implemented in 30 countries, covering 1.3 billion people and saving 3.7 million lives. The Bloomberg Initiative advocates for and assists governments in implementing proven policies and programmes to reduce tobacco use as outlined by the World Health Organisation’s MOPWER measures. “The Union welcomes this announcement at a time when awareness about tobacco as a common risk factor affecting non-communicable diseases is becoming more widespread. The global response to tobacco control will help support public health efforts in general to save more lives,” said Dr. Nils Billo, Executive Director of The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union). ELEASE The Union manages grants supported by the World Lung Foundation with generous financial assistance from the Bloomberg Initiative. Through the Bloomberg Initiative, The Union has supported over 80 R organisations in more than 30 countries. Some of the achievements to date have included: • Several countries have instituted smokefree laws, locally and on a national level. -

International Tobacco Control Organizations & Resources

International Tobacco Control Organizations and Resources / 1 Fact Sheet International Tobacco Control Organizations & Resources According to the World Health Organization, tobacco use is responsible for more than 5 million deaths each year, 80 percent of which occur in low- and middle-income countries. If current trends continue, tobacco use may cause close to one billion deaths in the 21st century.* Below is a list of leading organizations that work to advance tobacco control efforts worldwide, along with links to several of their most useful resources. Organizations Based in the United States Action on Smoking & Health (ASH) ASH is a Washington D.C.-based non-governmental organization, founded in 1967, which supports international tobacco control efforts. Working individually and through a large global network, ASH monitors industry behavior, pushes for stronger regulations at home and abroad, and ensures that tobacco is on the global agenda for health, trade, development and human rights. Available at http://ash.org. American Cancer Society (ACS) The Society’s global tobacco control program supports advocacy and research and builds the capacity of leaders and organizations in low- and middle-income countries to counter the tobacco industry’s efforts to undermine tobacco control policies. The program focuses in particular on sub-Saharan Africa, because the African continent is home to the highest increase in the rate of tobacco use in the developing world. Available at http://www.cancer.org/aboutus/globalhealth/globaltobaccocontrol/global-tobacco- control-landing. Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use Michael R. Bloomberg, philanthropist and mayor of New York, has launched a $375 million initiative to combat tobacco use in low- and middle-income countries, where more than two-thirds of the world’s smokers live. -

Global Tobacco Use and Cancer: Findings and Solutions from The

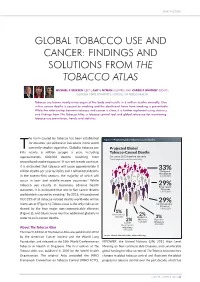

RISK FACTORS GLO BA L TOBACCO USE AND CANCER: F INDINGS AND SOLUTIO NS FROM THE TOBACCO ATLAS MICHAEL P ERIKSEN (LEFT) , AMY L NYMAN (CENTRE) AND CARRIE F WHITNEY (RIGHT) , GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SCHOOL O F P UBLIC HEALTH Tobacco use harms nearly every organ of the body and results in 6 million deaths annually. One in five cancer deaths is caused by smoking and the death and harm from smoking is preventable. While the relationship between tobacco and cancer is clear, it is further explained using statistics and findings from The Tobacco Atlas , a tobacco control tool and global reference for monitoring tobacco use prevalence, trends and statistics. he harm caused by tobacco has been established Figure 1: Projected global tobacco-caused deaths for decades, yet still one in five adults in the world Tcurrently smokes cigarettes. Globally, tobacco use Proje ct ed Gl obal kills nearly 6 million people a year, including Tobacco-Caused De aths approximately 600,000 deaths resulting from By c aus e, 201 5 b aseli ne sc enari o Tota ls mig ht no t sum due to r oundi ng. secondhand smoke exposure. 1 If current trends continue, it is estimated that tobacco will cause approximately 8 33% million deaths per year by 2030, and 1 billion total deaths Malig nant Neoplas ms 2,12 0,00 0 in the twenty-first cen tury , th e majo rity of which will occur in low- and mid dle -i nc ome co untries. 2 While tobacco use results in numerous adverse health 29% Res pir at or y outcomes, it is estimated that one in five cancer deaths Diseas es 1, 870,000 worldwide is caused by smoking. -

Michael Bloomberg Announces Grantees of $125 Million Initiative to Promote Freedom from Smoking

FROM: Rubenstein Communications – Public Relations Contact: Robert Lawson (212) 843-8040 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Michael Bloomberg Announces Grantees of $125 Million Initiative to Promote Freedom from Smoking New York City – Michael R. Bloomberg today named the five key partner organizations, which will implement his initiative, coordinating activities and providing grants to other organizations to promote freedom from smoking. The partners are the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Foundation, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the World Health Organization, and the World Lung Foundation. Bloomberg’s $125 million, two-year contribution is many times larger than any prior donation for global tobacco control and more than doubles the global total of private and public donor resources devoted to fighting tobacco use in developing countries, where more than two thirds of the world’s smokers live. All of the resources are dedicated outside the United States to specifically benefit low- and middle-income countries. “New York City has had tremendous success reducing tobacco use,” Bloomberg said. “As a result, there are nearly 200,000 fewer smokers in the city today than there were 4 years ago. If that kind of progress can be made on a global scale, we can save many millions of lives. This initiative will focus on getting results -- reducing tobacco use by proven means.” The five partner organizations will implement and coordinate activities to help stop the epidemic of tobacco use, working in partnership and close coordination with other organizations involved in international tobacco control. The four components of the initiative are listed below. -

WNTD Themes Design Update 2

World No Tobacco Day (WNTD) Themes A Review of WNTD themes and relationship to international policy measures, including influence and inputs by non-government and philanthropic entities. WNTD THEMES: A REVIEW MAY 2020 – PAGE 2 BRIEF HISTORY World No Tobacco Day is celebrated every year on May 31st One of eight global public health days marked by the World Health Organization (WHO), World No Tobacco Day (WNTD), was conceived to draw attention to the burden of preventable death and disease related to tobacco and nicotine use.1, 2 In 1987, the World Health Assembly called for April 7th of the following year–chosen to coincide with the WHO’s 40th anniversary–to be “a world no-smoking day.”2 This first-of-its-kind global tobacco control campaign aimed to provide assistance to tobacco users trying to quit by advocating for abstinence from tobacco use for 24 hours. Themed “Tobacco or Health: Choose Health,” the initiative was taken up by a number of countries who organized supporting activities to mark the day in their own territories, including public smoking bans in Ethiopia, suspension of tobacco sales in Cuba, poster contests in Spain, and public information campaigns in Lebanon and China. The press coverage and discourse generated by such activities suggested broad support for a range of tobacco control policy and health education measures.3 Two years later, in 1989, the 42nd Assembly passed resolution WHA42.19 during its 12th Plenary Meeting, affirming that “health services should clearly and unequivocally publicize the health risks connected with the use of tobacco and actively support all efforts to prevent the associated diseases.” This resolution went on to declare May 31st of each year going forward to be “World No Tobacco Day.”4 1 World Health Organization, WHO Global Health Days. -

Ethel Jane Carter, M.D

ETHEL JANE CARTER, M.D. The Miriam Hospital Divisions of Infectious Disease and Pulmonary/Critical Care 164 Summit Avenue, Providence, Rhode Island 02806 Tel: 401-793-2056 Fax: 401-793-4064 [email protected] EDUCATION Wellesley College, Wellesley, Massachusetts 1974-1978 • B.A. in Chemistry George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC 1978-1982 • M.D. POSTDOCTORAL TRAINING Internship Internal Medicine 1982-1983 Roger Williams Medical Center/Brown University Providence, Rhode Island Residency Internal Medicine 1983-1985 Roger Williams Medical Center/Brown University Providence, Rhode Island Chief Residency Internal Medicine 1985-1986 Roger Williams Medical Center/Brown University Providence, Rhode Island Fellowship Brown University Program in Pulmonary Medicine 1988-1990 Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island and Roger Williams Medical Center Providence, Rhode Island HONORS AND DISTINCTION Teacher of the Year Award, Roger Williams Medical Center 1991 • In recognition by the Internal Medicine Residency House staff to best faculty teacher Margaret Rawlings Lupton Service Award 1999 Girls Preparatory School, Chattanooga, Tennessee • In recognition to alumnae who exhibit exceptional citizenship and 1 service to the community in which they live. Physician of the Year Award, Rhode Island Medical Women’s Association 2001 • Awarded annually to a local female physician who has demonstrated excellence and a high level of commitment to medicine, family and the community Excellence in Teaching Award for Clinical Faculty, Brown -

Respiratory Diseases in the World Realities of Today – Opportunities for Tomorrow

This document aims to inform, raise awareness and assist those who advocate for protecting and improving respiratory health. It outlines practical approaches to combat threats to respiratory health, and proven strategies to significantly Respiratory diseases improve the care that respiratory professionals provide for individuals afflicted with these diseases worldwide. The report also calls for improvements in healthcare policies, in the world systems and care delivery, as well as providing direction for future research. Realities of Today – Opportunities for Tomorrow Forum of International Respiratory Societies Respiratory diseases in the world Realities of Today – Opportunities for Tomorrow Forum of International Respiratory Societies Respiratory diseases in the world Realities of Today – Opportunities for Tomorrow Print ISBN: 978-1-84984-056-9; e-ISBN: 978-1-84984-057-6 Edited and typeset by the European Respiratory Society publications offi ce, 442 Glossop Road, Sheffi eld, S10 2PX, UK. Image credits Front cover. Crowd reaching for globe. ©Martin Barraud, Getty Images. Pages 8/9. Talking to the mother of a TB patient. ©WHO/TBP/Gary Hampton, Courtesy of World Lung Foundation. Page 11. Man with COPD. ©Christine Schmid, Creatim. Page 13. Young man with spacer and inhaler. ©LHIL/Gary Hampton, Courtesy of World Lung Foundation. Page 15. Four children in Mozambique. Th e fi rst child, admitted with pneumonia, is being treated with oxygen. ©2006 Quique Bassat, Courtesy of Photoshare. Page 17. TB patient with mask. ©WHO/TBP/Davenport, Courtesy of World Lung Foundation. Page 19. A man smokes a cigarette outside his home in an urban village in Jakarta, Indonesia. ©2011 Colin Boyd Shafer, Courtesy of Photoshare. -

Progress in Tobacco Control in Egypt and Pakistan

WHO-EM/TFI/052/E PROGRESS IN TOBACCO CONTROL in Egypt and Pakistan Activities implemented by WHO under the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use Bloomberg Art Work -- ver02 Final.indd 1 4/11/2010 3:30:08 PM WHO-EM/TFI/052/E Progress in tobacco control in Egypt and Pakistan Activities implemented by WHO under the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Progress in tobacco control in Egypt and Pakistan: activities implemented by WHO under the Bloomberg initiative to reduce tobacco use / World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean p. WHO‐EM/TFI/052/E 1. Tobacco – Egypt ‐ Pakistan 2. Smoking – Egypt ‐ Pakistan 3. Tobacco Use Cessation 4. Regional Health Planning I. Title II Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (NLM Classification: WM 290) © World Health Organization 2010 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

“Sin Taxes” and Health Financing in the Philippines

C ASES IN G LOBAL H EALTH D ELIVERY GHD-030 OCTOBER 2015 “Sin Taxes” and Health Financing in the Philippines In April 2015, Dr. Enrique Ona stood before a diverse group of finance ministers from low- and middle-income countries at a finance leadership forum. The forum organiZers had invited him to serve as an “expert resource” during a session on the health and economic benefits of tobacco control. Ona had worked as a physician and seen the health effects of tobacco consumption before becoming health secretary of the Philippines, which had a very high smoking prevalence. Ona detailed to the ministers how the country had raised tobacco taxes after decades of opposition from the tobacco industry and allied politicians. The new legislation earmarked a majority of the revenues for health, enabling him to extend subsidiZed coverage under the government’s health insurance plan to all poor and near-poor Filipinos and invest in health facility upgrades. Although Ona had resigned from his post in late 2014, he remained concerned about the impact of the “sin tax” reforms on smoking prevalence and health care access. Could the initial decline in smoking be sustained long-term? Could the new revenues have the impact on national health that he hoped? Overview of the Philippines From the 16th until the late 19th century, the Philippines was under Spanish rule. During this time, Roman Catholic missionaries converted a majority of the population to Christianity, introduced tobacco farming, and built universities and hospitals.1 In 1898, Spain lost the Spanish-American War and ceded the islands to the United States (US; see Appendix for commonly used acronyms).2 In 1941, the US entered World War II, and Japan invaded the Philippines. -

THE TOBACCO ATLAS T H I R D E D I T I O N

THE TOBACCO ATLAS TH I RD ED I T I ON IN MEMORY OF JUDITH D. WILKENFELD (1943–2007) AND RONALD M. DAVIS (1956–2008) FOR THEIR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENTS IN BATTLING THE TOBACCO PANDEMIC THE TOBACCO ATLAS TH I RD ED I T I ON ALSO PUBL I SHED BY THE AMER I CAN CANCER SOC I ETY DR . OMAR SHAFEY DR . M I CHAEL ER I KSEN DR . HANA ROSS DR . J UD I TH MACKAY PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY 250 Williams Street Atlanta, Georgia 30303 USA CONTENTS www.cancer.org Copyright © 2009 American Cancer Society Forewords 8 All rights reserved. Without limiting under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, John R. Seffrin, CEO, American Cancer Society, and Peter Baldini, CEO, World Lung Foundation stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written consent of the publisher. Reviews 10 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Preface 11 ISBN-10: 1-60443-013-3 Acknowledgments 12 ISBN-13: 978-1-60443-013-4 Product Code: 967401 Photo Credits 14 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data About the Authors 15 The tobacco atlas / authors, Omar Shafey ... [et al.]. —3rd ed. p. cm. Glossary 16 Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-60443-013-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ParT ONE: PREVALENCE AND HEALTH 18 ISBN-10: 1-60443-013-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Tobacco use—Maps. 2. Tobacco industry—Maps.