Wildlife and Forest Crime Analytic Toolkit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stopping Poaching and Wildlife Trafficking Through Strengthened Laws and Improved Application

Stopping poaching and wildlife trafficking through strengthened laws and improved application Phase 1: An analysis of Criminal Justice Interventions across African Range States and Proposals for Action Initiating partners: Stop Ivory and the International Conservation Caucus Foundation (ICCF) Group Author: Shamini Jayanathan July 2016 Contents 1. LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................. 2 2. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 8 3. METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................... 9 4. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................... 10 5. KENYA .................................................................................................... 24 6. KEY RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................... 27 7. UGANDA ................................................................................................ 29 8. KEY RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................... 31 9. GABON .................................................................................................. 33 10. KEY RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................... 36 11. TANZANIA ............................................................................................ 37 12. KEY RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................. -

Financial Investigations Into Wildlife Crime

FINANCIAL INVESTIGATIONS INTO WILDLIFE CRIME Produced by the ECOFEL The Egmont Group (EG) is a global organization of Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs). The Egmont Group Secretariat (EGS) is based in Canada and provides strategic, administrative, and other support to the overall activities of the Egmont Group, the Egmont Committee, the Working Groups as well as the Regional Groups. The Egmont Centre of FIU Excellence and Leadership (ECOFEL), active since April 2018, is an operational arm of the EG and is fully integrated into the EGS in Canada. The ECOFEL is mandated to develop and deliver capacity building and technical assistance projects and programs related to the development and enhancement of FIU capabilities, excellence and leadership. ECOFEL IS FUNDED THROUGH THE FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF UKAID AND SWISS CONFEDERATION This publication is subject to copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission and consent from the Egmont Group Secretariat. Request for permission to reproduce all or part of this publication should be made to: THE EGMONT GROUP SECRETARIAT Tel: +1-416-355-5670 Fax: +1-416-929-0619 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2020 by the Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units ECOFEL 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms ..................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... -

An Analysis of the Situation of Children and Women in Kon Tum Province

PEOPLE’S COMMITTEE OF KON TUM PROVINCE AN ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE AN ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN 1 AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE AN ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE AckNOWLEDGEMENTS This Situation Analysis was undertaken in 2013-2014 as part of the Social Policy and Governance Programme, under the framework of the Country Programme of Cooperation between the Government of Viet Nam and UNICEF in the period 2012-2016. This publication exemplifies the strong partnership between Kon Tum Province and UNICEF Viet Nam. The research was completed by a research team consisting of Edwin Shanks, Buon Krong Tuyet Nhung and Duong Quoc Hung with support from Vu Van Dam and Pham Ngoc Ha. Findings of the research were arrived at following intensive consultations with local stakeholders, during fieldwork in early 2013 and a consultation workshop in Kon Tum in July 2014. Inputs were received from experts from relevant provincial line departments, agencies and other organisations, including the People’s Council, the Provincial Communist Party, the Department of Planning and Investment, the Department of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs, the Department of Education, the Department of Health, the Provincial Statistics Office, the Department of Finance, the Social Protection Centre, the Women’s Union, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Provincial Centre for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation, the Committee for Ethnic Minorities, Department of Justice. Finalization and editing of the report was conducted by the UNICEF Viet Nam Country Office. -

Summary of Evaluation Result

Summary of Evaluation Result 1. Outline of the Project Country: Socialist Republic of Vietnam Project Title: the project on the Villager Support for Sustainable Forest Management in Ventral Highland Issue/ Sector: Natural Environment Cooperation Scheme: Technical Cooperation Project Division in charge: JICA Vietnam office Total Cost: 251 million Yen Period of 3 years and 3 months from June Partner Country’s Implementation Cooperation 20, 2005 to September 19, 2008 Organization: (R/D): (R/D):Signed on April 12, 2005 - Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) - Division of Forestry, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD) of Kon Tum province - Kon Tum province Forestry Project Management Board Supporting Organization in Japan: Forestry Agency, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Related Cooperation: None 1-1 Background of the Project The Central Highlands in Vietnam is recognized as higher potential for forestry development because the area sustains large scale natural forest. The development on the forest resources in the area requires enough environmental consideration such as the ecological conservation, social and economical perspectives. This was recognized that the development of the forest resources also requires adequate forest management plan and its project implementation in accordance with the comprehensive development plan. Under those backgrounds, “The Feasibility Study on the Forest Management Plan in the Central Highlands in Socialist Republic of Vietnam” was conducted in Kon Tum Province from January 2000 to December 2002. The study targeted to Kon Plong district in the province. Based on the Forest resource inventory study and management condition of the forest enterprise, target area for the project implementation was identified and master plan for the forest management including plans for silvicultural development and support for villagers were proposed. -

Southeast Asia SIGINT Summary, 4 January 1968

Doc ID: 6636695 Doc Ref ID: A6636694 • • • • •• • • •• • • ... • •9 .. • 3/0/STY/R04-68 o4 JAN 68 210oz DIST: O/UT SEA SIGSUM 04-68 THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS CODEWORD MATERIAL Declassified and Approved for Release by NSA on 10- 03- 2018 pursuant to E . O. 13526 Doc ID: 6636695 Doc Ref ID: A6636694 TOP ~ECll~'f Tltf!rqE 3/0/STY/R04-68 04 Jan 68 210oz DIST: O/UT NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY SOUTHEAST ASIA SIGINT SUMMARY This report summarizes developments noted throughout Southeast Asia available to NSA at time of publication on 04 Jan 68. All information in this report is based entirely on SIGINT except where otherwise specifically indicated. CONTENTS PAGE Situation Summary. ~ . • • 4 • • • • • • • • 1 I. Corrnnunist Southeast Asia Military INon - Responsive IA. I 1. Vietnamese Corrnnunist Corrnnunications South Vietnam. • • • . • . •• . 2 2. DRV Corrnnunications .. ~ . 7 THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS i/11 PAGE(S) TOP ~~GRgf TaINi Doc ID: 6636695 Doc Ref ID: A6636694 TOP ~ECRET TRI~~E 3/0/STY/R04-68 SITUATION SUMMARY In South Vietnam, communications serving elements of the PAVN 2nd Division continue to reflect contact with Allied forces in ..:he luangNam-Quang Tin Province area of Military Region (HR:· : . n;_fficulties in mounting a planned attack on Dak To aLr:-fl.~l<l in Kontum Province were reported to the Military Intelligence Section, PAVN 1st Division by a subordinate on 3 Jan:ic.ry. In eastern Pleiku Province the initial appearance o:f cct,,su.:1icc1.t:ions between a main force unit of PAVN B3 Front and a provincial un:Lt in MR 5 was also noted. -

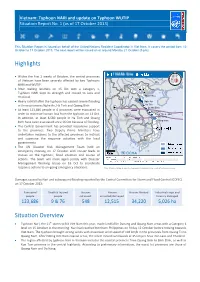

Highlights Situation Overview

Vietnam: Typhoon NARI and update on Typhoon WUTIP Situation Report No. 1 (as of 17 October 2013) This Situation Report is issued on behalf of the United Nations Resident Coordinator in Viet Nam. It covers the period from 12 October to 17 October 2013. The next report will be issued on or around Monday 21 October (5 pm). Highlights Within the first 2 weeks of October, the central provinces of Vietnam have been severely affected by two Typhoons NARI and WUTIP. After making landfalls on 15 Oct with a Category 1, Typhoon NARI kept its strength and moved to Laos and Thailand. Thanh Hoa Heavy rainfall after the typhoon has caused severe flooding Nghe An in three provinces Nghe An, Ha Tinh and Quang Binh Ha Tinh Quang Binh At least 123,686 people in 6 provinces were evacuated in Quang Tri order to minimize human loss from the typhoon on 14 Oct. Thua Thien - Hue In addition, at least 8,580 people in Ha Tinh and Quang Da Nang Binh have been evacuated since 16 Oct because of flooding. Quang Nam The Central Government has provided responsive support to the provinces. Two Deputy Prime Ministers have undertaken missions to the affected provinces to instruct and supervise the response activities with the local governments. The UN Disaster Risk Management Team held an emergency meeting on 17 October with cluster leads to discuss on the typhoon, flood situation and course of actions. The team will meet again jointly with Disaster Management Working Group on 18 Oct to coordinate response actions to on-going emergency situations. -

Decision No. 5811QD-Ttg of April 20, 2011, Approving the Master Plan On

Issue nos 04-06/Mtly2011 67 (Cong BaG nos 233-234IAprrI30, 2011) Decision No. 5811QD-TTg of April 20, lifting Kon Tum province from the poverty 2011, approving the master plan on status. socio-economic development of Kon 3. To incrementally complete infrastructure Turn province through 2020 and urbanization: to step up the development of a number of economic zones as a motive force for hoosting the development of difficulty-hit THE PRIME MINISTER areas in the province. Pu rsriant to the Dcccml.cr 25, 2001 Law 011 4. 10 achieve social progress and justice in Organization ofthe Government; each step of development. To pay attention to Pursuant to the Government :\' Decree No 92/ supporti ng deep-lying. remote and ethnic 2006/NDCP of September 7, 2006, Oil the minority areas in comprehensive development; formulatiou, approval and II1(1fWgClIlCllt of to conserve and bring into play the traditional socio-economic del'elopmem master plans and cultures ofethnic groups. Decree No. 04/2008/ND-CP of Januarv 11, 5. To combine socio-economic development 2008, amending and supplementing a number with defense and security maintenance; to firmly ofarticles ofDecree No. 92/2006/ND-C/': defend the national border sovereignty; to firmly At the proposal (if the PeOIJ! e's Committee maintain pol itical security and social order and ofKon Tum province, safety; 10 enhance friendly and cooperative relations within the Vietnam- Laos- Cambodia DECIDES: development triangle. Article I. To approve the master plan on II. DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES soc io-ccrmomic rl('v~lnpnH'nt of Kon Tum province through 2010, with the following I. -

Preliminary Checklist of Hoya (Asclepiadaceae) in the Flora of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam

Turczaninowia 20 (3): 103–147 (2017) ISSN 1560–7259 (print edition) DOI: 10.14258/turczaninowia.20.3.10 TURCZANINOWIA http://turczaninowia.asu.ru ISSN 1560–7267 (online edition) УДК 582.394:581.4 Preliminary checklist of Hoya (Asclepiadaceae) in the flora of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam L. V. Averyanov1, Van The Pham2, T. V. Maisak1, Tuan Anh Le3, Van Canh Nguyen4, Hoang Tuan Nguyen5, Phi Tam Nguyen6, Khang Sinh Nguyen2, Vu Khoi Nguyen7, Tien Hiep Nguyen8, M. Rodda9 1 Komarov Botanical Institute, Prof. Popov, 2; St. Petersburg, RF-197376, Russia E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vietnam Academy of Sciences and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Cau Giay, Ha Noi, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 3Quang Tri Center of Science and Technology, Mientrung Institute for Scientific Research, 121 Ly Thuong Kiet, Dong Ha, Quang Tri, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 4 3/12/3 Vo Van Kiet Street, Buon Ma Thuot City, Dak Lak province, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 5Department of Pharmacognosy, Hanoi University of Pharmacy, 15 Le Thanh Tong, Hoan Kiem, Hanoi, Vietnam E-mail: [email protected] 6Viet Nam Post and Telecommunications Group – VNPT, Lam Dong 8 Tran Phu Street, Da Lat City, Lam Dong Province, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 7Wildlife At Risk, 202/10 Nguyen Xi st., ward 26, Binh Thanh, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 8Center for Plant Conservation, no. 25/32, lane 191, Lac Long Quan, Nghia Do, Cau Giay District, Ha Noi, Vietnam E-mail: [email protected] 9Herbarium, Singapore Botanic Gardens, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569. -

Wildaid 2014 Annual Report

PAGE!2 OUR VISION WildAid’s mission is to end the illegal wildlife trade in our lifetimes. While most wildlife conservation groups focus on scientifc studies and protecting animals from poaching, WildAid works to reduce global consumption of wildlife products. Our primary strategy is mass media campaigning to reduce demand for these products with our slogan: “When the Buying Stops, the Killing Can Too.” Using the same tech- niques as high-end advertisers, we want to make conserva- tion aspirational and exciting. We also help to protect marine reserves, such as the Galápagos Islands in Ecuador and Misool Eco Resort in Indonesia, to safeguard sharks, mantas and other marine wildlife from direct threats such as overfishing. With a comprehensive management approach and appropriate technologies, WildAid delivers cost-efective enforcement to secure marine sanctuaries. PAGE!3 LETTER FROM THE FOUNDER In 2014, WildAid’s long-running shark fn campaign in China achieved widespread acclaim and recognition after a 50 to 70 percent reported decline in shark fn sales. This was the conclusion of multiple sources, from shark fn traders, to independent online and restaurant surveys, to media investigations from CNN, the Washington Post, the People’s Daily and CCTV, as well as government statistics. Vendors reported a 50 percent decrease in prices over the previous two years. Meanwhile, 85 percent of consumers surveyed online said they had given up shark fn soup in the past three years, with two-thirds citing public awareness campaigns as a main reason for ending their shark fn consumption. In Indonesia, fshermen reported it was no longer worth targeting sharks. -

Measuring Indicators for Landscape Change in Kon Tum Province, Vietnam

Modern Environmental Science and Engineering (ISSN 2333-2581) November 2019, Volume 5, No. 11, pp. 1009-1019 Doi: 10.15341/mese(2333-2581)/11.05.2019/004 Academic Star Publishing Company, 2019 www.academicstar.us Measuring Indicators for Landscape Change in Kon Tum Province, Vietnam Lai Vinh Cam, Nguyen Van Hong, Vuong Hong Nhat, Nguyen Thi Thu Hien, Nguyen Phuong Thao, Tran Thi Nhung, and Le Ba Bien Institute of Geography, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Vietnam Abstract: This paper’s aim is concentrated on measuring the difference in landscape visual character as an indicator of landscape change. Seven landscape character indicators are used for calculating in a study area in Kon Tum province, Vietnam; concluding Landscape Shape Index, Aggregation Index, Number of Patches, Patch Density, Patch Cohesion Index, Perimeter - Area Ratio, Percentage of Landscape. This set of indicators proposed in previous research by McGarigal and Marks (1995) and calculated with GIS, Fragstats software. These indicators also express the attributes of the component maps which we used for main input data are land-use map, digital elevation map and soil map. These are the necessary mapping materials for calculating the indicators. In the method is used in this paper, a value for each indicator will be assigned for each observation to capture the character of the landscape. They will be compared with each other and considered changes in the forest, agricultural, artificial and others. This work is replicable and transparent, and constitutes a methodological step for landscape indication, since it adds a reference value for analyzing differences in landscape character. -

41450-012: Preparing the Ban Sok-Pleiku Power Transmission

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 41450 February 2012 Preparing the Ban Sok–Pleiku Power Transmission Project in the Greater Mekong Subregion (Financed by the Japan Special Fund) Annex 6.1: Initial Environmental Examination in Viet Nam (500 KV Transmission Line and Substation) Prepared by Électricité de France Paris, France For Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Ban-sok Pleiku Project CONTRACT DOCUMENTS – TRANSMISSION LINE Package – VIETNAM FINAL REPORT 500kV TRANSMISSION SYSTEM PROJECT ANNEX 6.1 – 500kV TRANSMISSION LINE & SUBSTATION Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) In VIETNAM Annex 6.1– TL & S/S IEE in VIETNAM ADB TA 6481‐REG BAN‐SOK (HATXAN) PLEIKU POWER TRANSMISSION PROJECT 500 kV TRANSMISSION LINE AND SUBSTATION – FEASIBILITY STUDY INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION (IEE) For: Vietnam Section: Ban Hatxan (Ban-Sok)-Pleiku 500kVA Double Circuit Three Phased Transmission Line Project: 93.5 km, Kon Tum and Gia Lai Province. As part of the: ADB TA No. 6481-REG: Ban Hatxan (BanSok) Lao PDR to Pleiku Vietnam, 500kVA Transmission Line and Substation Construction Feasibility Study. Draft: June 2011 Prepared by Electricite du France and Earth Systems Lao on behalf of Electricite du Vietnam (EVN), and for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The views expressed in this IEE do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

First Report on the Amphibian Fauna of Ha Lang Karst Forest, Cao Bang Province, Vietnam

Bonn zoological Bulletin 66 (1): 37 –53 April 2017 First report on the amphibian fauna of Ha Lang karst forest, Cao Bang Province, Vietnam Cuong The Pham 1,4 , Hang Thi An 1, Sebastian Herbst 2, Michael Bonkowski 3, Thomas Ziegler 2,3 & Truong Quang Nguyen 1,3,4,5 1 Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet Road, Hanoi, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 AG Zoologischer Garten Köln, Riehler Strasse 173, D-50735 Cologne, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Institute of Zoology, Department of Terrestrial Ecology, University of Cologne, Zülpicher Strasse 47b, D-50674 Cologne, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Graduate University of Science and Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet Road, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Vietnam 5 Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. A total of 21 species of amphibians was documented on the basis of a new herpetological collection from the karst forest of Ha Lang District, Cao Bang Province. Three species, Odorrana bacboensis , O. graminea , and Rhacopho - rus maximus , are recorded for the first time from Cao Bang Province. The amphibian fauna of Ha Lang District also con - tains a high level of species of conservation concern with one globally and two nationally threatened species and three species, Odorrana mutschmanni , Gracixalus waza , and Theloderma corticale , which are endemic to Vietnam. Keywords : Amphibians, karst forest, distribution, diversity, new records, Cao Bang Province. INTRODUCTION MATERIAL & METHODS Recent herpetological research has underscored the spe - Field surveys were conducted in the Ha Lang forest of Cao cial role of karst habitats in promoting speciation of rep - Bang Province (Fig.