Galton Review Issue 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biology Things to Do

Post 16 Biology things to do: Competition: The Royal Society of Biology has a photography competition with the theme ‘our changing world’ more information can be found by following the link. https://www.rsb.org.uk/get-involved/rsb-competitions/photography-competition The prize for the winner of the under 18 competition is £500 Reading: We have split these reading lists into 3 categories, this is to give you an idea of how ‘easy’ the reading is – for example Bill Bryson’s ‘The Body’ whilst very factual and interesting is designed for the general population to read. On the other hand ‘Evolution in 4 dimensions’ is designed with a biologist in mind – if evolution is your thing – give it a go! Category 1 are the easiest reads and category 3 are the most difficult – but all worthwhile. Category 1 Category 2 Category 3 ‘The Body’ https://thebiologist.rsb.org.uk/biologist ‘Evolution in 4 dimensions’ Bill Bryson Eva Jablonka & Marion J.Lamb ‘A short history of nearly ‘Darwin comes to Town’ ‘The Epigenetics everything’ Memo Schilthuizen Revolution’ Bill Bryson Nessa Carey ‘Sapiens’ ‘The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks’ ‘The Cell: Discovering the Yuval Noah Harari Rebecca Skloot microscopic World that Determines our Health, Consciousness, and Our Future’ Joshua Z.Rappoport PhD, Barry Abrams et al. ‘Homo Deus’ ‘Evolution: The Human Story, 2nd ‘Life: an unauthorized Yuval Noah Harari edition’ biography’ Alice Roberts Richard Fortey ‘The Selfish Gene’ ‘The soul of an octopus’ Richard Dawkins Sy Montgomery ‘The Ancestor’s Tale’ ‘The Gene: An intimate history’ Richard Dawkins and Yan Siddhartha Mukherjee Wong ‘This is going to hurt’ ‘In the shadow of man’ Adam Kay Jane Goodall ‘Human Universe’ ‘The Book of Humans’ Brian Cox Adam Rutherford ‘Life on Earth’ David Attenborough ‘Anatomy and physiology for dummies’ Tasks Option 1: https://pbiol.rsb.org.uk/cells-to-systems/support-and-movement/observing-earthworm-locomotion The idea is to find Earthworms and compare their movement on different surfaces. -

EUGENICS, HUMAN GENETICS and HUMAN FAILINGS the Eugenics Society, Its Sources and Its Critics in Britain Pauline M.H.Mazumdar

EUGENICS, HUMAN GENETICS AND HUMAN FAILINGS The Eugenics Society, its sources and its critics in Britain Pauline M.H.Mazumdar London and New York 1992 CONTENTS List of illustrations vii Preface x INTRODUCTION 1 1 THE EUGENICS EDUCATION SOCIETY: THE TRADITION, THE 5 SETTING AND THE PROGRAMME 2 THE AGE OF PEDIGREES: THE METHODOLOGY OF EUGENICS, 40 1900–20 3 IDEOLOGY AND METHOD: R.A.FISHER AND RESEARCH IN 69 EUGENICS 4 THE ATTACK FROM THE LEFT: MARXISM AND THE NEW 106 MATHEMATICAL TECHN JQUES 5 HUMAN GENETICS AND THE EUGENICS PROBLEMATIC 142 EPILOGUE AND CONCLUSION 184 Notes 193 Bibliography 232 Frontispiece Pedigree of the Wedgwood-Darwin-Galton family, the model family of the eugenics movement EUGENICS, HUMAN GENETICS AND HUMAN FAILINGS What is the history of the British eugeriics movement? Why should it be of interest to how scientists work today? This outstanding study follows the history of the eugeriics movements from its roots to its heyday as the source of a science of human genetics. The primary contributions of the book are fourfold. First, it points to nineteenth-century social reform as contributing to the later eugenics movement. Second, it is based upon important archival material newly available to researchers. This material gives the reader an insight into the inner councils of the Society that could not have been obtained by relying upon published sources alone. Third, it treats the statistical methods involved in human genetics historically, in a way that allows the reader to follow their development and tie them to their context within the eugenics movement. -

Genetics Society News

July 2008 . ISSUE 59 GENETICS SOCIETY NEWS www.genetics.org.uk IN THIS ISSUE Genetics Society News is edited by Steve Russell. Items for future issues should be sent to Steve Russell, preferably by email to • Genetics Society Epigenetics Meeting [email protected], or hard copy to Department of Genetics, • Genetics Society Sponsored Meetings University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EH. The Newsletter is published twice a year, with copy dates of 1st June and • Travel, Fieldwork and Studentship Reports 26th November. • John Evans: an Appreciation Cocoons of the parasitoid wasp Cotesia vestalis on cabbage leaf in Taiwan. From the • Twelve Galton Lectures fieldwork report by Jetske G. de Boer on page 36. • My Favourite Paper A WORD FROM THE EDITOR A word from the editor ow soon until the $1000 based on the results of tests we genome is actually with barely understand! Here in the Hus and individual UK there is currently a sequencing is widespread? The moratorium, adhered to by publication of increasing most insurers, on the use of numbers of individual human genetic testing information for genome sequences suggests assessing life insurance that we should start to consider applications. It is important some of the implications that this remains in place and associated with the availability its effectiveness is reviewed of personal genetic well before the current information. In this issue we moratorium expires in 2011. present two articles reflecting The Human Genetics on his issue: a report from a Commission Genetics Society sponsored (http://www.hgc.gov.uk) meeting recently held in monitor issues relating to Cambridge organised by The genetic discrimination in the Triple Helix, an international UK and are a point of contact undergraduate organisation, as for those with any concerns in the Millennium Technology Prize. -

Even Scientists Can't Predict the Future – Or Can They? Edited by Jim Al

EVEN SCIEntists can’t prEDICT THE FUTURE – OR CAN THEY? Edited by Jim Al-Khalili PROFILE BOOKS What's Next?.indd 3 30/08/2017 16:25 First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Profile Books Ltd 3 Holford Yard Bevin Way London wc1x 9hd www.profilebooks.com 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Selection, introduction and Chapter 18 (‘Teleportation and Time Travel’) copyright © Jim Al-Khalili 2017 Other chapters copyright of the author in each case © Philip Ball, Margaret A. Boden, Naomi Climer, Lewis Dartnell, Jeff Hardy, Winfried K. Hensinger, Adam Kucharski, John Miles, Anna Ploszajski, Aarathi Prasad, Louisa Preston, Adam Rutherford, Noel Sharkey, Julia Slingo, Gaia Vince, Mark Walker, Alan Woodward 2017 The moral right of the authors has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. All reasonable efforts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if notified in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 1 78125 895 8 eISBN 978 1 78283 376 5 Text design by Sue Lamble Typeset in Sabon by MacGuru Ltd Printed and bound in Britain -

Applied Science (Equivalent to One a Level)

Applied Science (equivalent to one A Level) This is a programme of activities and resources to prepare you to start BTEC Applied Science in September. It is aimed to be used throughout the remainder of the Summer term and over the Summer Holidays to ensure you are ready to start your course in September. Book Recommendations The books below are all popular science books and great for extending your understanding of Science. Bryson and Goldacre are available as ebooks from Hampshire library service. https://www.hants.gov.uk/librariesandarchives/library/whatyoucanborrow/ebooksaudi obooks A Short History of Nearly Everything A whistle-stop tour through many aspects of history from the Big Bang to now. This is a really accessible read that will re-familiarise you with common concepts and introduce you to some of the more colourful characters from the history of science! Available at amazon.co.uk Periodic Tales: The Curious Lives of the Elements (Paperback) Hugh AlderseyWilliams ISBN-10: 0141041455 http://bit.ly/pixlchembook1 This book covers the chemical elements, where they come from and how they are used. There are loads of fascinating insights into uses for chemicals you would have never even thought about. Bad Science (Paperback) Ben Goldacre ISBN-10: 000728487X http://bit.ly/pixlchembook3 Here Ben Goldacre takes apart anyone who published bad / misleading or dodgy science – this book will make you think about everything the advertising industry tries to sell you by making it sound ‘sciency’. TV and film Recommendations You won’t find Jurassic Park on this list, but they are all great watching for a rainy day. -

Hell on Earth

01 CHAPTER 3 02 03 04 Hell on Earth 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 “Long is the way, and hard, that out of hell leads up to 13 light.” 14 John Milton, Paradise Lost 15 16 17 f you want to construct a picture of the earth on which life first 18 emerged, think about how we’ve named it. There are four geo- 19 logical eons spanning the earth’s 4, 540-million-year existence. 20 IThe most recent three names reflect our planet’s propensity for liv- 21 ing things, all referring to stages of life. The second eon is called the 22 Archean, which rather confusingly translates as “origins.” The third 23 eon is the Proterozoic, roughly translating from Greek as “earlier 24 life”; the current eon, the Phanerozoic, started around 542 million 25 years ago and means “visible life.” 26 But the first eon, the period from the formation of the earth up 27 to 3. 8 billion years ago, is called the Hadean, derived from Hades, 28 the ancient Greek version of hell. 29 Life does not merely inhabit this planet; it has shaped it and is 30 part of it. Not just in the current era of man-made climate change, S31 but all through life’s history on Earth, life has affected the rocks N32 9781617230059_Creation_TX_p1-278.indd 61 26/02/13 7:51 PM 62 CREATION 01 below our feet and the sky above us. And necessarily, the origin of 02 life is inseparable from the fury of the formation of the earth in the 03 first place. -

SYNTHETIC LIFE: How Far Could It Go? How Far Should It Go? WELCOME

SYNTHETIC LIFE: How far could it go? How far should it go? WELCOME Synthetic biology is a revolutionary technology that could have a huge impact on humans and our environment. The potential impact of this area of science is astonishing; from bacteria that could generate energy, to creating food without the need for large organisms. Synthetic biology is dividing opinion. Today’s speakers Professor Paul Freemont, Dr Louise Horsfall, Professor Robert Edwards, Dr Susan Molyneux-Hodgson and Chair Dr Adam Rutherford will discuss and debate this exciting topic and its possible applications. This event has been organised by the Biochemical Society and the Royal Society of Biology, as part of Biology Week 2015. We hope you enjoy the lively talks and thought-provoking debate. #BiologyWeek WHAT IS SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY? Synthetic biology is so new there isn’t one singular definition for it. It is based on the idea that engineering approaches can be used to study biological systems, manipulate them and to produce new ones that do not exist in nature. All living things contain DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), and it is found in every cell in our bodies. It is a unique code, made up of a sequence of chemicals. This sequence, called our genetic code or genome, determines how an organism is made; the same way the letters in the alphabet form words or sentences. Humans have been manipulating the genetic code for thousands of years, by selectively breeding plants and animals with desired characteristics. As we have learned how to read and manipulate the genetic code, we have started to take genetic information from one organism and transfer it to another. -

Australian Eugenics from 1900 to 1961

AUSTRALIAN EUGENICS FROM 1900 TO 1961 Nina N. Lemieux TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin Dec 1, 2017 Megan Raby, Ph.D. Department of History Supervising Professor George Christian, Ph.D. Department of English Second Reader Abstract Page/Info Author: Nina Lemieux Title: Australian Eugenics from 1900 To 1961 Supervising Professor: Professor Megan Raby, PhD In the first half of the 20th century, colonialism spread the eugenic movement to every inhabited continent. When eugenic ideology declined in the wake of World War II, only the American and German eugenics movements were studied and publicized extensively - the attitudes and policies of countries like Australia were forgotten or even actively buried. This thesis delves into how the eugenics movement specifically manifested in Australia, from who advocated for it to what kind of legislation was proposed, and examines why Australian eugenics presented differently from Britain and other British colonies Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge a number of advisors and friends for their help in completing this thesis. First, I’d like to thank Professor Megan Raby, who took on this project with me even though I lacked the typical history background requisite for such a large project. Professor Raby provided many suggestions that guided this thesis in its final direction. I would have been lost without her guidance and her patience has been so appreciated. I would also thank to thank Professor George Christian, my second reader, who has been the greatest fan of my life since I’ve arrived at The University of Texas. Professor Wetlauffer, if you are reading this, please present him the Chad Oliver Teaching Award because he embodies exactly what I came to UT to find. -

![OO3BE] 4 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTONOMA Ef DE MEXICO](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3769/oo3be-4-universidad-nacional-autonoma-ef-de-mexico-2853769.webp)

OO3BE] 4 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTONOMA Ef DE MEXICO

OO3BE] 4 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTONOMA ef DE MEXICO , FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DIVISION DE ESTUDIOS DE POSGRADO ALGUNOS ASPECTOS DE LA ESTERILIZACION EUGENETICA EN CALIFORNIA, DE 1900 a 1929. T E S I S QUE PARA OBTENER EL GRADO ACADEMICO DE MAESTRA EN CIENCIAS (BIOLOGIA) P R E $ E N T OA BIOL. MA. ALICIA VILLELA GONZALEZ DIRECTORA DE TESIS: DRA. EDNA SUAREZ DIAZ — MEXICO, D, F, 4999 TESIS CON | yan ALLA DE ORIGEN , UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. INDICE Agradecimientos Introduccion =p 1 Capitulo 1 1.1 La eugenesia como objeto de estudio de la historia p.8 1.2 La perspectiva de este trabajo p.17 2.0 Origenes de la eugenesia Introduccié6n p.20 2.1 Creacion del Banco Antropométrico p.22 2.1 Biometristas darwinianos p.29 2 3 El movimiento de eugenesia en los Estados Unidos p.31 2.3 1 Principales Lideres del movimiento de eugenesia en los Estados Unidos. Charles Davenport p 32 2.3.2. -

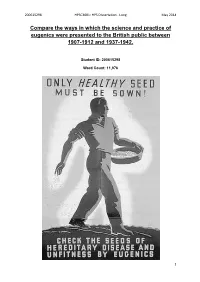

Compare the Ways in Which the Science and Practice of Eugenics Were Presented to the British Public Between 1907-1912 and 1937-1942

200615298 HPSC3601: HPS Dissertation - Long May 2014 Compare the ways in which the science and practice of eugenics were presented to the British public between 1907-1912 and 1937-1942. Student ID: 200615298 Word Count: 11,976 1 200615298 HPSC3601: HPS Dissertation - Long May 2014 0. Introduction 1. Historical Background 2. An original analysis of The Eugenics Review 3. An examination of four categories 4. Explaining eugenics to the British public 4.1. The inner circle: The Eugenics Review 4.2. Expanding the circle: leaflets 4.3. Heredity in Man: a film for all 5. The big change in eugenics 5.1. Eugenics as a solution to social problems 5.2. A move towards birth control 5.3. Focusing on population problems 6. Conclusion Bibliography 2 200615298 HPSC3601: HPS Dissertation - Long May 2014 0. Introduction 'Eugenics' is a term with powerful and emotive connotations. It conjures nightmarish images of genocide, the murder of over six million innocent citizens and sterilization of a further 400,000. It has become synonymous with Hitler's race hygiene which aimed to create the perfect race though the extermination of 'undesirable' groups such as the disabled, homosexuals and, in particular, Jews. The history of eugenics, however, is far more complex than this well-known account. This essay will explore the ways in which the British movement considered and presented eugenics. Eugenic-type ideas emerged in Britain from as early as the mid-19th Century as a result of increasing concerns about the fitness of the population and decline in birth rate. The publication of Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection in 1859 fuelled the idea that human selection and manipulation could be used to improve the population.1 The real starting point of eugenics is often attributed to Francis Galton who was a cousin of Darwin. -

Newsletter June 2008

ISSN 1359-9321 The Galton Institute NEWSLETTER Galtonia candicans Issue Number 67 June 2008 EDITORIAL wife, Julia Bodmer, and Rose Payne, Contents which contributed to the discovery of the HLA system. In 1970 he left his Profes- Presidency of sorship of Genetics at the Stanford The Galton Institute Medical School to become Oxford’s The Galton Institute, Professor of Genetics. He was elected New President 1 At the end of six active years as FRS in 1974 and in 1979 moved to President of the Galton Institute, London as Director of Research at the Conference 2008 2 for which, in acknowledging his Imperial Cancer Research Fund Labora- constant concern, we can here tories, becoming the first Director- General of the Fund in 1991. Retiring in Medicine may change warmly express sincere gratitude, 1996, he returned to Oxford as Principal our genes 4 Professor Steve Jones of Hertford College. Since the end of his has been succeeded by Professor tenure as Principal he has continued as Sir Walter Bodmer, on whom head of the Cancer and Immunogenetics The Human Genome 5 Anthony Edwards has provided Laboratory at the Weatherall Institute of the following note. Molecular Medicine, with a special Report of Innovation interest in cancer genetics, particularly and Evolution workshop 9 colorectal cancer. Sir Walter Bodmer, who gave the 2008 Galton Lecture Population genetics Knighted in 1986 for services to Genetic Testing: and the concept of individuality, became science, Sir Walter is a Foreign Associ- Uses and Limitation 10 a Fellow of the Eugenics Society in 1961 ate of the US National Academy of Sciences and the recipient of more than and served on the Council from 1971 to The Powers of Natural 1974. -

Newsletter September 2010

ISSN 1359-9321 The Galton Institute NEWSLETTER Galtonia candicans Issue Number 74 September 2010 Origins of Positive Eugenics in Britain Contents The term ‘positive eugenics’ came into Tracing the Trajectory prominence early in the history of of ‘Positive Eugenics’ eugenics, although not before the founda- Tracing the Trajectory of tion of the Eugenics Education Society in in Britain 1907. Several authors have credited its ‘Positive Eugenics’ in creation to Caleb Williams Saleeby by (1878-1940),64 an early leader of the Britain 1 eugenics movement. Saleeby was a gifted Anthony J. Dellureficio speaker and propagandist, though not an investigator. As such he was contentious Galton Institute in the eyes of many of the scientists in the Conference 2010 16 movement, although he played a signifi- What follows is Part 2 of a disserta- cant role by interpreting complicated tion submitted to the University of genetics issues for lay members of the Manchester for the degree of Master eugenics community. A letter he wrote to of Science in the Facultyof Life Francis Galton in 1909 lends support to Sciences. Part 1 appeared in the last Saleeby’s nature as a eugenic neologist. issue of the Newsletter. The letter asks Galton’s opinion on the term “dygenics versus kakogenics. I am for the former as neater and sufficiently correct” and expresses gratitude at Positive Eugenics in Britain Pearson “using my ‘eugenicist’ rather than ‘eugenician’.”65 The introduction of The general theory of eugenics in the term ‘positive eugenics’ did not come Britain arose from investigations into how without dissention, however. Numerous society affects evolution and ‘natural debates were recorded in the Eugenics selection’, and whether humans could Review, for example in 1910, Montague employ the laws of evolution to improve Crackanthorpe (1832-1913), second their social condition.