Hook, Warsash, Hampshire Excavations, 1954

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Old Common Gardens – Locks Heath – Southampton – Hampshire– SO31 6AX a Two-Bedroom Ground Floor Apartment in a Popular Retirement Development Close to Shops

12 Old Common Gardens – Locks Heath – Southampton – Hampshire– SO31 6AX A two-bedroom ground floor apartment in a popular retirement development close to shops 12 Old Common Gardens Entrance hall • Sitting room • Two Bedrooms • Kitchen • Bathroom £205,000 leasehold Old Common Gardens is situated off Locks Road which runs due south from Middle Road and connects to the main A27. The development adjoins woodland and playing fields on common land which once formed part of Swanwick Heath. A well-positioned two-bedroom ground floor apartment with access to terrace and garden area with double glazing and electric storage heating. Facilities include a resident manager, emergency alarm system in each property, lift, a residents’ lounge and communal laundry. There are also guest facilities that can be booked for visitors. Sitting Room Attractive landscaped gardens. Communications are excellent with the M27 at Junction 9 less than 3 miles. Fareham is about 5 miles and Southampton 6 miles. Wickham is 7 miles and Botley 6 miles. Fast trains from Swanwick, about 2 miles, to Southampton take about 20 minutes and to London (Paddington) about an hour and 50 minutes. Southampton Airport is about seven miles. 125 year lease (from 1987), £50 p.a. ground rent and 55+ age covenant. For viewings please contact the Scheme Manager on 01489 885409 or Bedroom Dining Room / Bedroom Fifty5plus on 01488 668655 The Property Directions to Old Common Gardens No 12 Old Common Gardens is an attractive two bedroom ground floor From the M27 Junction 9 take the A27 south and at the large roundabout corner apartment with approximate room dimensions as follows: Entrance take the 5th exit into Southampton Road. -

Al FAREHAM BOROUGH LOCAL PLAN Land Around Brook Avenue

Al FAREHAM BOROUGH LOCAL PLAN Land around Brook Avenue, Warsash, Hampshire Agricultural Land Classification ALC Map and Report February 1998 Resource Planning Team RPT Job Number: 1504/004/98 Eastern Region MAFF Reference:EL 15/00967 FRCA Reading AGRICULTURAL LAND CLASSIFICATION REPORT FAREHAM BOROUGH LOCAL PLAN LAND AROUND BROOK AVENUE, WARSASH, HAMPSHIRE INTRODUCTION 1. This report presents the findings of a detailed Agricultural Land Classification (ALC) survey of 40 hectares of land at Brook Avenue, Warsash on the Hampshire coast between Southampton and Portsmouth. The survey was carried out during February 1998. 2. The survey was undertaken by the Farming and Rural Conservation Agency (FRCA) * on behalf of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF), in connection with MAFF's statutory input lo the Fareham Borough Local Plan. This survey supersedes any previous ALC information for this land. 3. The work was conducted by members of the Resource Planning Team in the Eastern Region of FRCA. The land has been graded in accordance with the published MAFF ALC guidelines and criteria (MAFF, 1988). A description of the ALC grades and subgrades is given in Appendix 1. 4. At the time of survey the land in agricultural use on the site consisted of penmanenl grassland grazed by ponies and areas of rough grassland. Most of the survey area consists of 'Other land' the majorily of which comprises residential areas and the remainder is woodland, trackways and nurseries. SUMMARY 5. The findings of the survey are shown on the enclosed ALC map. The map has been drawn at a scale of 1:10,000. -

Volunteers Make the Most of Warsash

Warsash in Westminster - Suella Braverman MP supporting our community 1000 attend Suella’s A brighter future THE LATEST NEWS Solent Festival of Engineering for Brexit FROM YOUR LOCAL InTouch COUNCILLORS AND MP Despite Brexit turbulence, with Warsash and Hook unemployment remains at a record low, wages are rising faster FarehamWinter 2019 Local Elections 3rd May 2018 than prices and the economy is growing faster than forecast. As I wrote in the Daily Telegraph, no- one can doubt the Prime Minister’s GIVING YOU A VOICE indefatigable pursuit of a Brexit Deal. However, it was with regret that I voted against the original deal in Keeping Council Suella was delighted to hold Navy, Air Force and many others to Parliament in January. That deal was Tax down - again the first ever Solent Festival of enable young people to learn more not Brexit. It would have locked the U.K. indefinitely into the EU’s single Engineering at Fareham Leisure about the opportunities from further With a further loss of central market and customs union whilst Centre which was attended by over study and careers in the field. From government financial support annexing Northern Ireland so that it 1000 local children and students. virtual reality, rocket cars, coding Fareham Borough Council has challenges, 3D printing, Lego building, would be treated as a 3rd country The aim of the event was to showcase increased its share of Council Tax drones, model railways, AI, learning by Great Britain. I sincerely want to the busy the myths about Engineering, by just £5 per year representing about wi-fi, jet engines and gas support a Government Deal and am Photograph courtesy of Adam Shaw technology and the sciences. -

Locks Heath, Sarisbury and Warsash

LOCKS HEATH, SARISBURY AND WARSASH Character Assessment 1 OVERVIEW .....................................................................................................................................2 2 CHARACTER AREA DESCRIPTIONS..............................................................................7 2.1 LSW01 Sarisbury......................................................................................................................7 01a. Sarisbury Green and environs.....................................................................................................7 01b. Sarisbury Green early suburbs....................................................................................................8 2.2 LSW02 Warsash Waterfront .......................................................................................... 12 2.3 LSW03 Park Gate District Centre................................................................................ 14 2.4 LSW04 Locks Heath District Centre........................................................................... 16 2.5 LSW05 Coldeast Hospital................................................................................................. 18 2.6 LSW06 Industrial Estates (Titchfield Park).............................................................. 21 06a. Segensworth East Industrial Estate......................................................................................... 21 06b. Matrix Park .............................................................................................................................. -

Park Gate Titchfield Sarisbury Locks Heath Warsash Titchfield Common Reference Item No

ZONE 1 - WESTERN WARDS Park Gate Titchfield Sarisbury Locks Heath Warsash Titchfield Common Reference Item No P/14/0321/FP 290 BROOK LANE - BROOK LANE REST HOME - SARISBURY 1 PARK GATE GREEN SOUTHAMPTON SO31 7DP PERMISSION PROPOSED GROUND FLOOR EXTENSION TO REAR TO ALLOW RE-ORGANISATION OF EXISTING ACCOMMODATION AND CIRCULATION SPACE AND THE PROVISION OF THREE ADDITIONAL BEDROOMS. WIDENING OF VEHICULAR ACCESS FROM BROOK LANE AND RE-CONFIGURATION OF CAR PARKING TO PROVIDE THREE ADDITIONAL PARKING SPACES P/14/0340/FP 63 BRIDGE ROAD PARK GATE SOUTHAMPTON SO31 7GG 2 PARK GATE PROPOSED BUILDING OF TWO THREE BEDROOM CHALET PERMISSION BUNGALOWS TO THE REAR OF 63 BRIDGE ROAD USING THE EXISTING SITE ENTRANCE. P/14/0368/FP 1 LOWER CHURCH ROAD FAREHAM HAMPSHIRE PO14 4PW 3 [O] PROPOSED FIRST-FLOOR EXTENSION OVER GARAGE, TO PERMISSION TITCHFIELD ACHIEVE THE PROVISION OF A ONE-BEDROOMED ANNEXE. COMMON P/14/0405/FP 54 BEACON WAY PARK GATE SOUTHAMPTON SO31 7GL 4 PARK GATE PROPOSED FIRST FLOOR SIDE EXTENSION, REAR DORMER PERMISSION WINDOW AND THREE ROOF LIGHTS IN THE FRONT ROOF SLOPE P/14/0415/FP LAND TO THE SOUTH WEST SIDE OF BURRIDGE ROAD 5 SARISBURY BURRIDGE ROAD BURRIDGE SOUTHAMPTON SO31 1BY PERMISSION REDESIGN OF AN EXISTING PITCH, INCLUDING RELOCATION OF THE CARAVANS AND UTILITY/DAY ROOM GRANTED FOR RESIDENTIAL PURPOSES FOR 1 NO GYPSY PITCH WITH THE RETENTION OF THE GRANTED HARD STANDING ANCILLARY TO THAT USE P/14/0429/FP 5 EASTBROOK CLOSE PARK GATE SOUTHAMPTON SO31 7AW 6 [O] FRONT SINGLE STOREY EXTENSION AND ALTERATIONS PERMISSION PARK GATE P/14/0455/FP -

Eastleigh Borough Local Plan 2011-2029 Draft October 2011

Eastleigh Borough Local Plan 2011-2029 Draft October 2011 Foreword Foreword This document is a first draft of the Borough Council’s ideas for a new plan for the borough, looking ahead to 2029. We need this because our existing plan (the Eastleigh Borough Local Plan Review 2001-2011) is now out of date. There have been many changes nationally and locally since it was adopted, and we must have new policies to address these. Preparing a new plan has given the Council a chance to look afresh at what sort of places and facilities we need for our communities now and in the future. To establish what our priorities should be, we have investigated a wide variety of existing and future needs in the borough. From these we have developed a draft plan to help guide development over the next 18 years. The plan is being published for public consultation, and the Borough Council would welcome your views on our draft policies and proposals, and how we should be making provision for the future. We are still at an early stage in the process, and your views can help shape the future of the borough. Full contact details are given in Chapter 1, Introduction. Foreword Chapter 1 Introduction Draft Eastleigh Borough Local Plan 1 2011-2029 Contents Page 1. Introduction 2 What is this about? What should I look at? How can I get involved? What happens next? How to use this document 2. Eastleigh Borough – key characteristics and issues 7 3. Vision and objectives 35 4. Towards a strategy 42 5. -

Hook Park, Warsash Hampshire Price Guide £1,775,000

HOOK PARK, WARSASH HAMPSHIRE PRICE GUIDE £1,775,000 www.penyards.com www.onthemarket.com www.rightmove.co.uk www.equestrianandrural.com LYNEHAM LODGE COWES LANE, WARSASH, HAMPSHIRE, SO31 9HD A truly spectacular residence, which has undergone a substantial extension and refurbishment program, the result is a thoughtfully designed and executed home extending to 3700 square feet, situated in a prime location SUMMARY OF FEATURES commanding outstanding panoramic views across the nature reserve and beyond across Southampton water and Re-roofed 2013. set in glorious gated grounds of half an acre. Solid oak double glazed leaded windows by Heritage fitted in 2013 Lyneham Lodge is a striking home with origins dating back to the 1930’s, the property enjoys a tucked away New electrics 2013. position approached via a private lane. My clients purchased the property 3 years ago and have sympathetically New plumbing 2013 with traditional style renovated to an exceptional standard with no expense, thought or effort spared during its refurbishment radiators throughout. program, care has been taken to retain its original charm and character with the integrity of the property well New Worcester boiler 2013. preserved. The accommodation is impressive throughout with a generous entrance hall and 5 reception areas on Newly sandblasted oak beams throughout. the ground floor, including a stunning glass and oak ‘live in’ kitchen/breakfast/family room with a mezzanine Beautiful original solid oak flooring to snug over, this area is exceptional with extensive bespoke cupboards with granite working surfaces, island unit Entrance Hall, Study and Sitting Room. and integral appliances and overlooks the delightful gardens. -

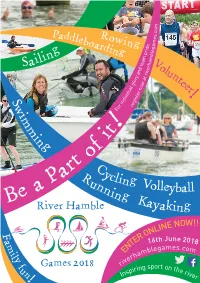

Be a Part of It

P a S d a d ili l n g e b S o R w a r o i d w m i i n n m g o g c m . s e, e id am r g p i e m bl n a te d am n h a r g ry e V o iv gl r al t o u a vid w di o l r in n Fo ter u is eg r n t e B e e ! a t r pa r o i t f ! F R a C m u y i n c l l y n i i n f n g u g n V ! o K l a le y y a ba k ll i ENT E R ONL n IN g 16 E riverha t N mb h O le Ju W Ins ga n ! piri m e ! ng e 2 sp s 0 or .c 1 t o 8 on m th e r iv e r At Hamble Yacht Services you’re just minutes from the central Solent when you launch from our dockside. Dry Stack spaces are available at our Dry Sail launch and recovery Dry Boat is available for New secure boatyard with the convenience of packages are available for racing cruising motor and sailing unlimited launches and retrievals, pressure yachts to suit your programme. yachts up to 14m (46ft). wash and return to stack 7 days a week. A gleaming hull is a race winner. Enjoy fuel efficiency, less maintenance With only one hour’s notice required it’s and slower depreciation. -

'Here's Another Fine Mess They've Gotten Us Into'

CONSERVATIVES – Two decades of exceptional civic service TITCHFIELDIn & TITCHFIELDTouch COMMON – Spring 2019 ‘Here’s another fine mess they’ve gotten us into’ pend the Draft Plan and take it back to the drawing board. Keith Evans led fierce Council opposition to the changes, but IT READS like a Laurel and Hardy farce, but for intensive lobbying of Housing Minister Kit Malthouse and senior Fareham planners the mess they have been gotten civil servants by the Council Leader and Fareham and Gosport into by the Government is no laughing matter. MPs fell on deaf ears. In less than a year, yet more green fields have come under threat He stated: “Government ignored our objections and is proceed- as Whitehall demands the Borough Council finds space for up to ing with the new mechanisms – although it conceded on one point 2,500 extra homes. and will introduce the measuring against new numbers effectively And these come on top of the 2,300 houses we have already from 2020 rather than being backdated. been forced to add to the new Draft Plan 2011-2036. “We are working through the numbers, but it looks certain to “What an awful Government-inspired mess this has been,” said be in the range of 1,800 to 2,500 more houses above the original Executive Member for Planning and Development Councillor additional 2,300 – an enormous increase and one which will have Keith Evans. to be met in the main from further new greenfield sites.” To meet the original target of 2,300, the Council proposed hav- Fortunately, the suspended Draft Plan remains valid while the ing as much brownfield development as possible, plus large new Council confirms the extra numbers and evaluates all the remain- greenfield sites in Warsash, Portchester, Titchfield Common and ing green space in Fareham. -

5. Fareham 5.1 About Fareham the Borough of Fareham Is a Coastal

5. Fareham 5.1 About Fareham The Borough of Fareham is a coastal, mainly urban district lying between the cities of Southampton and Portsmouth. The largest settlements are Fareham town, Portchester, Locks Heath and Stubbington, with a large new development planned at Welborne, north of Fareham town. The district also includes Titchfield Haven, a well-known nature reserve and the point where the River Meon flows out to the Solent. Fareham borders the River Hamble to the west, Winchester district to the north and Gosport to the south and has a short boundary with Portsmouth to the east. The district is unparished. The principal road corridors through Fareham are the east-west M27, the parallel A27 further south and the A32, which runs north to Alton and south to Gosport. Fareham is the sole through-route for commuting into/out of Gosport, which together with high traffic flows along the motorway mean that routes through Fareham can be congested. There are local rail connections to Eastleigh, Southampton, Portsmouth and Brighton. Fareham has strong economic links with Portsmouth and many people who work in Portsmouth live in Fareham. The Solent Enterprise Zone at the former naval airfield HMS Daedalus lies mainly within Fareham. This is a significant commercial development which is expected to bring 3,500 jobs into the borough by 2025. The population of Fareham in 2015 is around 114,000. Development in Fareham in recent times has been spread all over the borough. Stubbington grew substantially after the Second World War but elsewhere in the borough the environmental constraints around Titchfield, the various water boundaries and the nature of the Gosport peninsula have meant that development has been slower than in many other parts of the county. -

Submitted Eastleigh Borough Local Plan (2016-2036) Track Change

ED33 Submitted Eastleigh Borough Local Plan (2016-2036) Track change version showing initial proposed modifications July 2019 Please note that this track change version of the modified plan doesn’t show revisions to existing policy numbers, paragraph numbers or to any of the existing page number cross-references currently included. This is because of the likelihood of these changing further as policies and supporting text are subject to detailed discussions as part of the examination hearings. These will all be revised accordingly where required at the post examination stage. ED33 Foreword This document is Eastleigh Borough Council’s new plan for the Borough which looks ahead to 2036. We need a new plan because our existing plan (the Eastleigh Borough Local Plan Review 2001 - 2011) is now out of date. There have been many changes nationally and locally since it was adopted and we must have new policies to address these. Preparing a new plan has given the Council a chance to look afresh at what sort of places and facilities we need for our communities now and in the future. To establish what our priorities should be, we have investigated a wide variety of existing and future needs in the Borough. From these we have developed a plan to help guide development over the coming years up to 2036. Much of the development needed already has planning permission and the plan sets out the number of dwellings and location of sites with planning permission. The Council has been gathering evidence to inform decisions about the additional growth needed that cannot be located in existing urban areas. -

A River's Story Human Presence Around the River Hamble Dates Back

A River’s Story Human presence around the river Hamble dates back into pre•history. From its banks early man found a ready source of food in the form of fish, shellfish, wildfowl and game; forests in which to hide whenever danger threatened; timber to build dugout canoes; and ready access to a water highway for trade and contact with other communities. Unsurprisingly, this bountiful area was heavily populated in Neolithic times. Stone tools and other relics are still being found. Little is known of its history from Roman times to the middle ages, when the village of Hamble•Le•Rice, better known as ‘Hamble’ was founded near the river’s mouth. A few centuries later, the village of Warsash was founded on the opposite bank to Hamble•Le•Rice, and the villages of Bursledon and Swanwick, again on opposite sides of the river, were founded two miles or so north of the river’s mouth, partly to serve the needs of travellers, mostly between Portsmouth and Southampton, who needed to be ferried across the river. The river’s sheltered waters, forested banks and ready access to the sea created the ideal conditions for a shipbuilding industry, whose evidence can be seen throughout much of its length, but whose best known product was Nelson’s ship flagship at the battle of Copenhagen, HMS Elephant. The yard that built it now builds yachts; but is still known as the ‘Elephant’ boatyard and located next to a popular watering hole known as ‘The Jolly Sailor’, that enjoyed a brief period of fame as Tom Howard’s local during a BBC television series ‘Howard’s Way’.