Post-Brexit Citizenship Status: Divided by the Rules?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

227Th COMMISSION MEETING Held Via Microsoft Teams

28 September 2020 227th COMMISSION MEETING Held via Microsoft Teams Present: Les Allamby, Chief Commissioner Helen Henderson Jonathan Kearney David A Lavery CB Maura Muldoon Eddie Rooney Stephen White In attendance: David Russell, Chief Executive Rhyannon Blythe, Director (Legal, Research and Investigations, and Advice to Government) Claire Martin, Director (Communications, Information and Education, Public and Political Affairs) Hannah Russell, Director (Legal, Research and Investigations, and Advice to Government) Jacqueline McClintock, Finance, Personnel and Corporate Affairs Officer (Agenda items 1-3) Rebecca Magee, Personal Assistant (Agenda items 3-10) Lorraine Hamill, Director (Finance, Personnel and Corporate Affairs) (Agenda items 5-6) Nikita Brijpaul, Boardroom Apprentice The Chief Commissioner welcomed everyone to the first meeting of the new Commission Board and also welcomed Nikita Brijpaul who is the Commission’s Boardroom Apprentice for 2020-21. 1 1. Apologies and Declarations of Interest 1.1 There were no apologies. 1.2 There were no declarations of interest. 2. Minutes of the 226th Commission meeting and matters arising 2.1 The minutes of the 226th Commission meeting held on 24 August 2020 were agreed as an accurate record. Action: 226th Commission meeting minutes to be uploaded to the website. 2.2. The minutes of the closed meeting held on 24 August 2020 were agreed as an accurate record. 2.3 It was noted that the Chief Commissioner had written to the Northern Ireland Office regarding the Commission’s powers. A copy of the Opinion the Commission had received was also included with the letter. A response has not yet been received (item 2.3 of the 226th minutes refers). -

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Oral Evidence: Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol, HC 157

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Oral evidence: Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol, HC 157 Wednesday 16 June 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 16 June 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Simon Hoare (Chair); Scott Benton; Mr Gregory Campbell; Stephen Farry; Mary Kelly Foy; Mr Robert Goodwill; Claire Hanna; Fay Jones; Ian Paisley; Bob Stewart. Questions 941-1012 Witnesses I: The Rt Hon. Lord David Frost CMG, Minister of State for the Cabinet Office, and Mark Davies, Deputy Director, Transition Task Force Northern Ireland, Cabinet Office. Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Lord Frost and Mark Davies. Q941 Chair: Good morning, colleagues, and welcome to this session of our inquiry into Brexit and the Northern Ireland protocol. May I ask if any colleagues have any declarations of interest before we begin the meeting? Ian Paisley: I am involved in a legal action against the protocol with a number of commercial entities. Q942 Chair: Thank you. Lord Frost, you heard that, so that is under advisement, as it were. Minister, let me begin by establishing a few basic facts, because I think there is some uncertainty in the media and in the world of politics. Hopefully this will be a sort of quickfire yes or no round to get us into second gear. Could you confirm that Her Majesty’s Government negotiated with the European Union the Northern Ireland protocol? Lord Frost: Thank you, Chairman, and good morning. Before I answer that question, I would like to make one remark up front. It is a pleasure to be here today. -

Green Party Assembly Manifesto 2016

A Zero Waste Strategy for Northern Ireland The Green Party manifesto for the Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2016 1 Green Party in Northern Ireland | Manifesto 2016 Introduction The Green Party is We hate waste, wherever it is found, and pledge to bring about an end to the standing on a promise waste of money, time and opportunities of Zero Waste. at Stormont. By taking a Zero Waste approach to our economy, society and environment, we can make Northern Ireland a better place for us all to live. Green Party candidates for the 2016 Northern Ireland Assembly Elections 2 3 Green Party in Northern Ireland | Manifesto 2016 Contents Foreword 7 A Zero Waste Strategy for People 8 Education 8 Health 9 Justice 10 Arts 10 Equality 10 Democracy 11 A Zero Waste Strategy for the Environment 12 Planning 12 Natural resources 12 Agriculture 13 Animals 13 A Zero Waste Strategy for the Economy 14 Energy 14 Jobs 15 Housing 16 Transport 16 Green Party candidates 2016 17 4 5 Green Party in Northern Ireland | Manifesto 2016 Our Green Party councillors in North Down brought about a ban on circuses using animals on council Foreword property. They have supported community workers speaking out against paramilitary intimidation and have In the past five years, the Green Party’s been working towards giving the public a say in how membership has trebled, and continues to rise. money is spent. Our share of the vote has doubled between Westminster elections and we had our best ever Equality and social justice, inextricably linked with council election. -

2012 Biennial Conference Layout 1

Biennial Delegate Conference | 2012 City Hotel, Derry 17th‐18th April 2012 Membership of the Northern Ireland Committee 2010‐12 Membership Chairperson Ms A Hall‐Callaghan UTU Vice‐Chairperson Ms P Dooley UNISON Members K Smyth INTO* E McCann Derry Trades Council** Ms P Dooley UNISON J Pollock UNITE L Huston CWU M Langhammer ATL B Lawn PCS E Coy GMB E McGlone UNITE Ms P McKeown UNISON K McKinney SIPTU Ms M Morgan NIPSA S Searson NASUWT K Smyth USDAW T Trainor UNITE G Hanna IBOA B Campfield NIPSA Ex‐Officio J O’Connor President ICTU (July 09 to 2011) E McGlone President ICTU (July 11 to 2013) D Begg General Secretary ICTU P Bunting Asst. General Secretary *From February 2012, K Smyth was substituted by G Murphy **From March 2011 Mr McCann was substituted, by Mr L Gallagher. Attendance At Meetings At the time of preparing this report 20 meetings were held during the 2010‐12 period. The following is the attendance record of the NIC members: L Huston 14 K McKinney 13 B Campfield 18 M Langhammer 14 M Morgan 17 E McCann 7 L Gallagher 6 S Searson 18 P Dooley 17 B Lawn 16 Kieran Smyth 19 J Pollock 14 E McGlone 17 T Trainor 17 A Hall‐Callaghan 17 P McKeown 16 Kevin Smyth 15 G Murphy 2 G Hanna 13 E Coy 13 3 Thompsons are proud to work with trade unions and have worked to promote social justice since 1921. For more information about Thompsons please call 028 9089 0400 or visit www.thompsonsmcclure.com Regulated by the Law Society of Northern Ireland March for the Alternative image © Rod Leon Contents Contents SECTION TITLE PAGE A INTRODUCTION 7 B CONFERENCE RESOLUTIONS 11 C TRADE UNION ORGANISATION 15 D TRADE UNION EDUCATION, TRAINING 29 AND LIFELONG LEARNING E POLITICAL & ECONOMIC REPORT 35 F MIGRANT WORKERS 91 G EQUALITY & HUMAN RIGHTS 101 H INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS & EMPLOYMENT RIGHTS 125 I HEALTH AND SAFETY 139 APPENDIX TITLE PAGE 1 List of Submissions 143 5 Who we Are • OCN NI is the leading credit based Awarding Organisation in Northern Ireland, providing learning accreditation in Northern Ireland since 1995. -

Constituency Office Expenses2017-2018 Establishment Expenses

Constituency Office Expenses2017-2018 Establishment Expenses Agnew, Steven Transaction Transaction Account Name Expenditure Description Supplier Name Date Amount Members Office - Waste Disposal 17-Oct-17 £72.80 Council - Oct - Dec 17 Steven Agnew MLA Office Utilities - Water 26-Jul-17 £79.10 Feb - Jul 17 Northern Ireland Water Office Utilities - Water 05-Feb-18 £85.96 Aug 17 - Jan 18 Northern Ireland Water Office Utilities - Electricity 05-May-17 £79.14 Feb - Apr 17 SSE Airtricity Energy Supply (NI) L Office Utilities - Electricity 30-Jun-17 £44.74 Apr - Jun 17 SSE Airtricity Energy Supply (NI) L Office Utilities - Electricity 02-Nov-17 £11.52 Aug - Oct 17 SSE Airtricity Energy Supply (NI) L Office Utilities - Electricity 30-Jan-18 £36.96 Oct - Dec 17 SSE Airtricity Energy Supply (NI) L Members Office - Telephones 10-May-17 £139.33 May 17 British Telecommunications PLC Members Office - Telephones 22-Aug-17 £210.90 Aug 17 British Telecommunications PLC Members Office - Telephones 27-Nov-17 £176.77 Nov 17 British Telecommunications PLC Members Office - Telephones 12-Feb-18 £206.36 Feb 18 British Telecommunications PLC Members Office Equipment - Non Capital 19-Feb-18 £67.99 Argos - Oil Heater Steven Agnew MLA Members ICO Registration 30-Jun-17 £35.00 Jun 17 Information Commissioner's Office Sundry Expenditure 26-May-17 £20.00 May 17 Steven Agnew MLA Sundry Expenditure 01-Aug-17 £50.00 Jul 17 Steven Agnew MLA Sundry Expenditure 29-Aug-17 £91.60 Aug 17 Steven Agnew MLA Sundry Expenditure 17-Oct-17 £39.00 Sep 17 Steven Agnew MLA Sundry Expenditure -

Non-Nationalist Politics in a Bi-National Consociation: the Case of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland

1 Non-nationalist politics in a bi-national consociation: the case of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland David Mitchell Trinity College Dublin at Belfast Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 24:3, 1-12. 2018 Through a case study of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland, this article examines the contention that consociational power-sharing, in its determination to include dominant and conflicting identity groups, exalts these identities and excludes others including gender, class and other ethnicities and nationalities. The article describes and assesses the Alliance Party’s arguments that the power-sharing arrangements in Northern Ireland are philosophically objectionable, practically ineffective, and politically detrimental to parties which, like Alliance, are designated as ‘others’. The article finds that the party’s critique of consociationalism as implemented in Northern Ireland is overstated and that the party has been able to play a number of pivotal roles in the new politics. Northern Ireland’s Belfast/Good Friday Agreement is one of the most studied consociational settlements.1 The 1998 accord (hereafter ‘the Agreement’) appeared to enable the region’s transition out of decades of political violence and exclusion, making Northern Ireland, for many analysts, “the key confirming case for consociational theory”.2 However, the Agreement has also faced an array of academic, political and civil society detractors, many of whom have focussed on the specific criticism of consociational power-sharing which is the subject of this special section: that in its determination to include the dominant and conflicting national identity groups, consociationalism exalts these identities and excludes others, including gender, class and other ethnicities and nationalities.3 This article examines the ‘exclusion amid inclusion dilemma’ through the case study of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland. -

Article the Empire Strikes Back: Brexit, the Irish Peace Process, and The

ARTICLE THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK: BREXIT, THE IRISH PEACE PROCESS, AND THE LIMITATIONS OF LAW Kieran McEvoy, Anna Bryson, & Amanda Kramer* I. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................610 II. BREXIT, EMPIRE NOSTALGIA, AND THE PEACE PROCESS .......................................................................615 III. ANGLO-IRISH RELATIONS AND THE EUROPEAN UNION ...........................................................................624 IV. THE EU AND THE NORTHERN IRELAND PEACE PROCESS .......................................................................633 V. BREXIT, POLITICAL RELATIONSHIPS AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN NORTHERN IRELAND ....637 VI. BREXIT AND THE “MAINSTREAMING” OF IRISH REUNIFICATION .........................................................643 VII. BREXIT, POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND THE GOVERNANCE OF SECURITY ..................................646 VIII. CONCLUSION: BREXIT AND THE LIMITATIONS OF LAW ...............................................................................657 * The Authors are respectively Professor of Law and Transitional Justice, Senior Lecturer and Lecturer in Law, Queens University Belfast. We would like to acknowledge the comments and advice of a number of colleagues including Colin Harvey, Brian Gormally, Daniel Holder, Rory O’Connell, Gordon Anthony, John Morison, and Chris McCrudden. We would like to thank Alina Utrata, Kevin Hearty, Ashleigh McFeeters, and Órlaith McEvoy for their research assistance. As is detailed below, we would also like to thank the Economic -

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard)

Committee for Finance and Personnel OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard) Defamation Act 2013: Briefing from Mike Nesbitt MLA on Proposed Private Member’s Bill 26 June 2013 NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY Committee for Finance and Personnel Defamation Act 2013: Briefing from Mike Nesbitt MLA on Proposed Private Member’s Bill 26 June 2013 Members present for all or part of the proceedings: Mr Daithí McKay (Chairperson) Mrs Judith Cochrane Mr Leslie Cree Ms Megan Fearon Mr Paul Girvan Mr John McCallister Mr Adrian McQuillan Mr Peter Weir Witnesses: Mr Mike Nesbitt MLA Northern Ireland Assembly Mr Brian Garrett The Chairperson: I welcome to the meeting Mike Nesbitt MLA and Mr Brian Garrett, a solicitor. Mike, do you want to make some opening comments? Mr Mike Nesbitt (Northern Ireland Assembly): Thank you, Chair. On behalf of Brian, I make a plea that everyone speaks up a little. First of all, thank you very much for your time and for the Committee interest in this issue. I begin by declaring an interest with regard to Paul Tweed, whom I know socially and professionally. I hope that that will not change because we appear to be on different sides of the fence on this, although I am not sure that we are that far apart. As he said towards the conclusion of his evidence, it is virtually impossible to get satisfaction under the current regime here, so it seems to me that it may not be a question of whether we should change the law on defamation in this jurisdiction but how we change it. I think that perhaps that is the issue. -

Mike Nesbitt (UUP), Committee for the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister

Mike Nesbitt (UUP), Committee for the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister My name's Mike Nesbitt, I'm one of the 108 MLAs here at the Northern Ireland Assembly. I represent the constituency of Strangford. I'm also the leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, and in that capacity, I chair the Committee of the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister, or OFMDFM. OFMDFM is one of the 12 departments in the Northern Ireland Executive, and each one has what's called a statutory committee, which monitors what they get up to. If you were looking for one word about the work of the committee of OFMDFM, I think that word is "scrutiny." And that doesn't mean that we criticise, it simply means we look at what they're doing and what they're proposing to do, and we make recommendations when we think they could do it better. Or, indeed, we praise them if we think that they're doing it well. TBUC – Together Building a United Community When I was young in the early 1970s, I remember one night my father put me in a car and drove me up the Craigantlet Hills in East Belfast, and we watched Belfast burning as Catholics burned Protestants out of streets, and Protestants burned Catholics out of streets. And we now live in a largely segregated society. Of course, we have segregated schools and all the rest. And politically, we don't want that. We want people to share space, and to share experiences. -

0 the Tories' Social Care Scandal

0 The Tories’ social care scandal - Claire Tyler & Margaret Lally 0 Government ‘worse than incompetence’ - Paul Clein 0 Time for universal basic income - Paul Hindley Issue 401 - June 2020 £ 4 Issue 401 June 2020 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Commentary .......................................................................3 Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Radical Bulletin ...................................................................4..7 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at THE PEOPLE THEY FORGOT .........................................8..9 our website: www.liberator.org.uk It was too little, too late when the Government tried to protect care homes from Covid-19, leading to a scandal of needless deaths, Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to say Claire Tyler and Margaret Lally “Liberator Publications”, together with your name and full postal address, to: BLOOD ON THEIR HANDS ...........................................10..11 The Tory Government’s response to the pandemic has been marked by Liberator Publications something even worse than incompetence, says Paul Clein Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove London N4 2LF OWNERSHIP FOR ALL ...................................................12..13 England An old Liberal idea of universal ownership can be matched with a newer one of universal basic income for a post-pandemic world, THE LIBERATOR says Paul Hindley COLLECTIVE THERE GOES THE HIGH STREET ................................14..15 Jonathan Calder, Richard -

The Implications of Brexit for Civil Society and the Peace Process

The Implications of Brexit for Civil Society and the Peace Process Distinguished guests and colleagues, Like many of the Members of the European Economic and Social Committee who are here today, I am not a native English speaker. But there is one word that I have added to my English vocabulary in recent months: 'backstop'! The definition of the word 'backstop' is quite technical. But the symbolism that it has taken on since the Brexit negotiations began, is truly profound. I would not be surprised if in the future, dictionaries add a new meaning directly linking the word to the Brexit negotiations! As a German from Berlin, I fully understand both the symbolism and the impact of physical barriers and walls. I understand the need to look forward instead of backwards and how this shapes our identity. As a European, I am convinced that our most valued assets are Peace, Democracy and Partnership. And although not everyone here agrees on what the impact of Brexit will be on the Island of Ireland, there is no doubt that all of us, the other 27 EU Member States, European civil society and the European Institutions, will do everything in our means to ensure that the spirit of cooperation enshrined in the Good Friday Agreement, continues in your minds and in your daily lives. It is for this reason that we, civil society from the 28 EU Member States, are here today in Belfast. We are here to listen to your concerns, your fears and your hopes. We are here to reach out a hand to civil society on both sides of the border. -

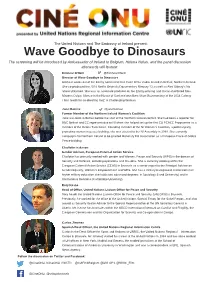

Wave Goodbye to Dinosaurs

The United Nations and The Embassy of Ireland present: Wave Goodbye to Dinosaurs The screening will be introduced by Ambassador of Ireland to Belgium, Helena Nolan, and the panel discussion afterwards will feature: Eimhear O'Neill @EimhearONeill Director of Wave Goodbye to Dinosaurs Eimhear works out of the Emmy nominated Fine Point Films studio, based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. She co-produced the 2018 Netflix Originals Documentary Mercury 13 as well as Alex Gibney’s No Stone Unturned. She was an associate producer on the Emmy-winning and Oscar-shortlisted Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God and won Best Short Documentary at the 2014 Galway Film Fleadh for co-directing Inez: A Challenging Woman. Jane Morrice @janemorrice Former Member of the Northern Ireland Women's Coalition Jane was born in Belfast before the start of the Northern Ireland conflict. She had been a reporter for BBC Belfast and EC representative to NI when she helped set up the first EU PEACE Programme as a member of the Delors Task Force. Founding member of the NI Women’s Coalition, a political party promoting women in peace building, she was elected to the NI Assembly in 1998. She currently campaigns for Northern Ireland to be granted Honorary EU Association as a European Place of Global Peace building Charlotte Isaksson Gender Advisor, European External Action Service Charlotte has primarily worked with gender and Women, Peace and Security (WPS) in the domain of Security and Defence, including operations and missions. She is currently working within the European External Action Service (EEAS) in Brussels as a senior expert to the Principal Advisor on Gender Equality, Women's Empowerment and WPS.