Dirleton Castle Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

34 Dirleton Avenue, North Berwick, East Lothian, Eh39 4Bh Former Macdonald Marine Hotel Staff Accommodation Building

34 DIRLETON AVENUE, NORTH BERWICK, EAST LOTHIAN, EH39 4BH FORMER MACDONALD MARINE HOTEL STAFF ACCOMMODATION BUILDING FOR SALE PRIME DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY Prime development opportunity in highly desirable coastal town of North Berwick Non-listed building occupying a generous plot of 0.5 acres (0.20 ha) Potential for redevelopment to high quality apartments, single house or flatted development (subject to planning) 25-miles from Edinburgh City Centre Moments from world-renowned golf courses and High Street amenities Total Gross Internal Area approximately 846.28 sq m (9,108 sq ft) Inviting offers over £1,353,000 ex VAT FOR SALE | PRIME DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY ALLIED SURVEYORS SCOTLAND | 2 LOCATION AND SITUATION North Berwick is one of Scotland’s most affluent coastal towns with a population of approximately 14,000 people. With its world-renowned links golf courses, vibrant town centre and white sandy beaches, the East Lothian town is highly sought after by visitors, residents and investors. Situated approximately 25 miles east of Scotland’s capital city, Edinburgh, it benefits from close proximity to the A1 trunk road. The town’s train station, meanwhile, provides regular direct services to Edinburgh Waverley, talking around 30 minutes to reach the city centre. The subjects are situated in a residential district on Dirleton Avenue, the principal route leading into and out of North Berwick, at the crossroads with Hamilton Road. The property is less than 1-mile away from the town’s High Street where a wide range of amenities are on offer including many independent shops, restaurants, galleries, coffee houses and boutiques. FOR SALE | PRIME DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY ALLIED SURVEYORS SCOTLAND | 3 DESCRIPTION The subjects comprise a second smaller access further a substantial four-storey down Hamilton Road leading to a single garage and driveway. -

Arrow-Loops in the Great Tower of Kenilworth Castle: Symbolism Vs Active/Passive ‘Defence’

Arrow-loops in the Great Tower of Kenilworth castle: Symbolism vs Active/Passive ‘Defence’ Arrow-loops in the Great Tower of Kenilworth ground below (Fig. 7, for which I am indebted to castle: Symbolism vs Active/Passive ‘Defence’ Dr. Richard K Morris). Those on the west side have hatchet-shaped bases, a cross-slit and no in- Derek Renn ternal seats. Lunn’s Tower, at the north-east angle It is surprising how few Norman castles exhibit of the outer curtain wall, is roughly octagonal, arrow-loops (that is, tall vertical slits, cut through with shallow angle buttresses tapering into a walls, widening internally (embrasure), some- broad plinth. It has arrow-loops at three levels, times with ancillary features such as a wider and some with cross-slits and badly-cut splayed bases. higher casemate. Even if their everyday purpose Toy attributed the widening at the foot of each was to simply to admit light and air, such loops loop to later re-cutting. When were these altera- could be used profitably by archers defending the tions (if alterations they be)7 carried out, and for castle. The earliest examples surviving in Eng- what reason ? He suggested ‘in the thirteenth cen- land seem to be those (of uncommon forms) in tury, to give crossbows [... ] greater play from the square wall towers of Dover castle (1185-90), side to side’, but this must be challenged. Greater and in the walls and towers of Framlingham cas- play would need a widening of the embrasure be- tle, although there may once have been slightly hind the slit. -

Dirleton Castle Geschichte

Dirleton Castle Geschichte Rundgang durch das Dirleton Castle Das „Äußere“ Castle Der Burggraben und die Verteidigungsmauer Das Vorhaus Das Torhaus Das „Innere“ Castle Der Innenhof Die Ruthven Lodging Die Türme der de Vauxs Der Halyburton- Trakt Die Gartenanlagen Die Familie de Vaux Kriegerische Zeiten Die Familie Halyburton Die Familie Ruthven Cromwell und die letzte Belagerung Das letzte Aufblühen - 1 - Dirleton Castle Geschichte Seit 700 Jahren thront das Dirleton Castle schon auf dem Felsen hoch über der reichen Baronie Dirleton. Das Castle ist der Inbegriff der trutzigen Stärke und Pracht einer mittelalterlichen Burg. Die Geschichte ist eng mit der Geschichte der Familien verknüpft, die hier lebten – die de Vaux, die Halyburtons und die Ruthvens. Die Gebäude entsprachen ihren Bedürfnissen und spiegelten ihren Status wider. Dabei hatten eine gezielte Planung und der Erhalt des Alten jedoch eine geringere Priorität, als die aktuelle Mode und die Bemühung mit allen Kräften den Nachbarn deutlich sichtbar zu übertrumpfen. Die eindruckvolle Festung wurde im Jahre 1220 von John de Vaux, nachdem die Familie in den Besitz der Ländereien von Gullane und Dirleton gekommen war, als Ersatz für eine ältere Burg errichtet, die man hier ein Jahrhundert zuvor gebaut hatte. Nach dem die Burg den Erben von John de Vaux 400 Jahre als Wohnsitz gedient hatte, wurde sie verlassen, geriet aber nicht in Vergessenheit. Heute wacht sie über die eleganten Gartenanlagen ihrer späteren Besitzer, die die Burgruine als besonders Zierstück in ihren Garten integrierten. - 2 - Dirleton Castle Rundgang durch das Dirleton Castle Der Rundgang beginnt bei den Wehranlagen, dem „Äußeren“ Castle und führt durch die Inneren Gebäudes, dem Inneren Castle und endet in den Gartenanlagen. -

LOCAL LIFE Template

LOCAL FEB | MAR 2020 LIFECOMMUNITY & LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE NOTHING SAYS LOVE LIKE ARTISAN CHOCOLATE www.thechocolatestag.co.uk CONTENTS THIS ISSUE A Sweet Tradition 4 Look what we Found! 5 relaxed living Fashion | Spring’s Nature Inspired Palette 9 Go Green at Old Smiddy 14 Interiors | Rules for Renting 18 Out of the Wood 19 Interiors | Inspired Colour 22 Food and Drink | Chocolate Chestnut Pot 24 26 Out & About elcome to our Leonardo Da Vinci: A Life in Drawing 28 first issue of the Head to the Hill 30 new decade. And for us, 31 Wthe first issue in our new home. We’re Stories in Stone | Lauderdale House excited to have moved into the Lighthouse, Dates for your Diary, Useful Numbers & Tide Times 32 in North Berwick and to be working Mind, Body & Soul | Be Free to be Who You Truly Are 34 alongside other businesses and creatives with a diverse range of skills. Mind, Body & Soul | 21 Day Self-Love Challenge 35 Yoga Poses for New Beginnings 36 The start of a new year brims with 37 excitement, new trends, new beginnings Competition | win a Personal Training Session and, of course, new year’s resolutions. Ah, 39 Health | Could I have a Dental Implant? new year’s resolutions – those things you Gardening | Ten Jobs to do in the Garden in February 42 embark upon with such gusto at the start 50 of the year, determined that this will be And Finally the year! Then, as always, life gets in the way and even with the best intentions, your resolutions do not always come to fruition. -

Medieval Castle

The Language of Autbority: The Expression of Status in the Scottish Medieval Castle M. Justin McGrail Deparment of Art History McGilI University Montréal March 1995 "A rhesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fu[filment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Am" O M. Justin McGrail. 1995 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*u of Canada du Canada Aquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie SeMces seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellingîon Street 395, nie Wellingtm ûîtawaON K1AON4 OitawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive Licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distniuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papet or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels rnay be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. H. J. B6ker for his perserverance and guidance in the preparation and completion of this thesis. I would also like to recognise the tremendous support given by my family and friends over the course of this degree. -

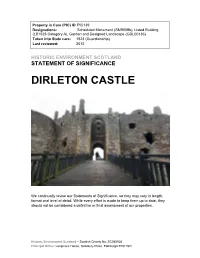

Dirleton Castle

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC 139 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90096), Listed Building (LB1525 Category A), Garden and Designed Landscape (GDL00136) Taken into State care: 1923 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2012 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DIRLETON CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DIRLETON CASTLE SYNOPSIS Dirleton Castle, in the heart of the pretty East Lothian village of that name, is one of Scotland's oldest masonry castles. Built around the middle of the 13th century, it remained a noble residence for four centuries. Three families resided there, and each has left its mark on the fabric – the de Vauxs (13th century – the cluster of towers at the SW corner), the Haliburtons (14th/15th century – the entrance gatehouse and east range) and the Ruthvens (16th century – the Ruthven Lodging, dovecot and gardens). The first recorded siege of Dirleton Castle was in 1298, during the Wars of Independence with England. The last occurred in 1650, following Oliver Cromwell’s invasion. However, Dirleton was primarily a residence of lordship, not a garrison stronghold, and the complex of buildings that we see today conveys clearly how the first castle was adapted to suit the changing needs and fancies of their successors. -

Historyofscotlan10tytliala.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Report on the Current State- Of-Art on Protection

REPORT ON THE CURRENT STATE- OF-ART ON PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION OF HISTORICAL RUINS D.T1.1.1 12/2017 Table of contents: 1. INTRODUCTION - THE SCOPE AND STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT ........................................................................... 3 2. HISTORIC RUIN IN THE SCOPE OF THE CONSERVATION THEORY ........................................................................... 5 2.1 Permanent ruin as a form of securing a historic ruin .................................................................... 5 2.2 "Historic ruin" vs. "contemporary ruin" ............................................................................................ 6 2.3 Limitations characterizing historic ruins ....................................................................................... 10 2.4 Terminology of the conservation activities on damaged objects ............................................... 12 3. RESEARCH ON HISTORIC RUINS ................................................................................................................................ 14 3.1. Stocktaking measurements ............................................................................................................. 14 3.1.1. Traditional measuring techniques .............................................................................................. 17 3.1.2. Geodetic method ............................................................................................................................ 19 3.1.3. Traditional, spherical, and photography -

Gullane to North Berwick on the John Muir Way

Gullane to North Berwick on the John Muir Way Start: Gullane Finish: North Berwick Distance: 10 km / 6 miles (one way) Time: 2½ - 3 hours (one way) Terrain: Pavements, Farm Tracks and grass paths. Directions: Follow the John Muir Way east along Gullane’s Main Street. Half a mile outside the village go through a timber gate and follow the track through the woods, cross the access road for Archerfield Links and then follow a track to the right, which brings you out in Dirleton. Follow the signs for the John Muir Way to your left and continue down a farm track to Yellowcraig. Continue along the path around the edge of the woodland and across a field and then go through another timber gate leading to a grass path along the edge of North Berwick Golf Club. The path comes out at the end of Strathearn Road and the route then follows pavements to the centre of North Berwick. Points of interest: 1. Gullane – A lovely village very much built around golf. The ruined St Andrews’ Kirk dates from the 1100s and was built to replace a church built in 800. 2. Archerfield House – Originally built in the 17th Century and remodelled in the 18th Century, Archerfield House fell into disrepair and was used as a farm store. The house was completely renovated in 2001. 3. Dirleton Castle – The earliest parts of the castle date from the 1200s. The castle was damaged and rebuilt several times over the next few centuries and eventually abandoned in the 1600s. The castle was then acquired by the Nisbet family, who went on to build Archerfield House. -

East Lothian Council LIST of APPLICATIONS DECIDED by THE

East Lothian Council LIST OF APPLICATIONS DECIDED BY THE PLANNING AUTHORITY FOR PERIOD ENDING 21st February 2020 Part 1 App No 19/01045/AMC Officer: Caoilfhionn McMonagle Tel: 0162082 7231 Applicant Mr Jason McGibbon Applicant’s Address 44 Kings Cairn Archerfield Dirleton East Lothian EH39 5EX Agent Aitken Turnbull Architects Agent’s Address Per Aitken Turnbull 9 Bridge Place Galashiels TD1 1SN Proposal Approval of matters specified in conditions of planning permission in principle 17/00823/PP - Erection of 1 house and associated works Location 37 Kings Cairn Archerfield Dirleton North Berwick East Lothian Date Decided 18th February 2020 Decision Application Permitted Council Ward North Berwick Coastal Community Council Gullane Area Community Council App No 19/01082/P Officer: Ciaran Kiely Tel: 0162082 7995 Applicant Mr A Short Applicant’s Address Zephyrs Nunraw Barns Garvald Haddington East Lothian EH41 4LW Agent McDonald Architecture & Design Agent’s Address Per Derek McDonald Townhead Steading East Saltoun Tranent East Lothian Proposal Conversion of former sawmill building to form 1 house with domestic workshop and associated works Location Nunraw Barns Old Sawmill Garvald Gifford East Lothian Date Decided 21st February 2020 Decision Application Refused Council Ward Haddington And Lammermuir Community Council Garvald & Morham Community Council App No 19/01090/P Officer: Sinead Wanless Tel: 0162082 7865 Applicant Mrs V Smith Applicant’s Address 58 Vinefields Pencaitland Tranent East Lothian EH34 5HD Agent McDonald Architecture & Design -

St Andrews Castle

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC034 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90259) Taken into State care: 1904 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2011 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ST ANDREWS CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH ST ANDREWS CASTLE SYNOPSIS St Andrews Castle was the chief residence of the bishops, and later the archbishops, of the medieval diocese of St Andrews. It served as episcopal palace, fortress and prison.