Sharon's Noranian Turn: Stardom, Embodiment, and Language in Philippine Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

Women in Filipino Religion-Themed Films

Review of Women’s Studies 20 (1-2): 33-65 WOMEN IN FILIPINO RELIGION-THEMED FILMS Erika Jean Cabanawan Abstract This study looks at four Filipino films—Mga Mata ni Angelita, Himala, Ang Huling Birhen sa Lupa, Santa Santita—that are focused on the discourse of religiosity and featured a female protagonist who imbibes the image and role of a female deity. Using a feminist framework, it analyzes the subgenre’s connection and significance to the Filipino consciousness of a female God, and the imaging of the Filipino woman in the context of a hybrid religion. The study determines how religion is used in Philippine cinema, and whether or not it promotes enlightenment. The films’ heavy reference to religious and biblical images is also examined as strategies for myth-building. his study looks at the existence of Filipino films that are focused T on the discourse of religiosity, featuring a female protagonist who imbibes the image and assumes the role of a female deity. The films included are Mga Mata ni Angelita (The Eyes of Angelita, 1978, Lauro Pacheco), Himala (Miracle, 1982, Ishmael Bernal), Ang Huling Birhen sa Lupa (The Last Virgin, 2002, Joel Lamangan) and Santa Santita (Magdalena, 2004, Laurice Guillen). In the four narratives, the female protagonists eventually incur supernatural powers after a perceived apparition of the Virgin Mary or the image of the Virgin Mary, and incurring stigmata or the wounds of Christ. Using a feminist framework, this paper through textual analysis looks at the Filipino woman in this subgenre, as well as those images’ connection and significance to the Filipino consciousness of a female God. -

Dr. Riz A. Oades Passes Away at Age 74 by Simeon G

In Perspective Light and Shadows Entertainment Emerging out Through the Eye Sarah wouldn’t of Chaos of the Needle do a Taylor Swift October 9 - 15, 2009 Dr. Riz A. Oades passes away at age 74 By Simeon G. Silverio, Jr. Publisher & Editor PHILIPPINES TODAY Asian Journal San Diego The original and fi rst Asian Philippine Scene Journal in America Manila, Philippines | Oct. 9, It was a beautiful 2008 - My good friend and compadre, Riz Oades, had passed away at age 74. He was a “legend” of San Diego’s Filipino American Community, as well day after all as a much-admired academician, trailblazer, community treasure and much more. Whatever super- Manny stood up. His heart latives one might want to apply was not hurting anymore. to him, I must agree. For that’s Outside, the rain had how much I admire his contribu- stopped, making way for tions to his beloved San Diego Filipino Americans. In fact, a nice cool breeze of air. when people were raising funds It had been a beautiful for the Filipinos in the Philip- day after all, an enchanted pines, Riz was always quick to evening for him. remind them: “Don’t forget the Bohol Sunset. Photo by Ferdinand Edralin Filipino Americans, They too need help!” By Simeon G. I am in Manila with my wife Silverio, Jr. conducting business and visit- Loren could be Publisher and Editor ing friends and relatives. I woke up at 2 a.m. and could not sleep. Asian Journal When I checked my e-mail, I San Diego read a message about Riz’s pass- temporary prexy The original and fi rst ing. -

Miguel Castro Biographical Information

CV Miguel Castro MIGUEL CASTRO (Gregorio Enrico Garcia Castro) BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION Place of Birth: Lipa City, Batangas, Philippines Nationality: Filipino Height: 173 cm Weight: 75 kg Hair Color: Brown/Grey Eye Color: Brown Address: 27 Wyoming Avenue Oatlands, NSW 2117 Mobile: 0420648214 e-mail: [email protected] Webpage: https://miguelcastro.art/ ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS Elementary: Lipa City South Central School, Lipa Batangas, From Grade One to Grade 6 High School: The Mabini Academy, Lipa City Batangas, Graduated March 1985 University: Lyceum of the Philippines, Intramuros, Manila, 3rd Year Mass Communication TRAINING • 1982-1986 Bookbinding Apprenticeship Tayuman, Manila, Philippines • 1989 Gantimpala Acting Workshop, Gantimpala Theatre Foundation Manila Metropolitan Theatre, Lawton, Manila, Philippines • 1989-1994 Company actor/production work apprentice for Gantimpala Theatre Foundation, Manila Metropolitan Theatre, Lawton, Manila, Philippines 1 CV Miguel Castro • 2005-2006 Private Vocal Training under Lionel Guico University of the Philippines, Music Department, Manila, Philippines • 2007-2015 Private Vocal Training under Pablo Molina, Quezon City, Philippines • 21-23.6.2019 Anthony Brandon Wong Acting Workshop, Sydney, Australia Business Experiences • 1992-2019 Castro Designs Paper Products Manufacturing and Local Distributing Company, Manila, Philippines • 1998-2003 Castro Designs Paper Products Manufacturing and Exporting Company, Quezon City, Philippines • 1998-2003 Castro Designs retail gift shops chain, SM North Quezon City, Mega Mall Mandaluyong, Robinsons Galleria Pasig City, Robinsons Place Manila, Philippines Agents • 2005-2016 Bibsy Carballo Talent Management, Manila, Philippines • May 2019-present Focus Talent Management, Sydney, Australia ARTIST INFO – Actor/Singer/Visual Artist Miguel Castro started his career as a stage actor with one of the oldest theatre companies in Manila, Philippines, Gantimpala Theatre Foundation, in 1989. -

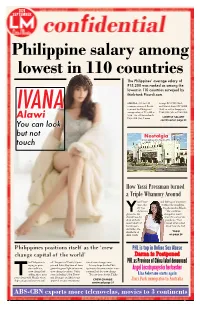

1 Angel Locsin Prays for Her Basher You Can Look but Not Touch How

2020 SEPTEMBER Philippine salary among lowest in 110 countries The Philippines’ average salary of P15,200 was ranked as among the Do every act of your life as if it were your last. lowest in 110 countries surveyed by Marcus Aurelius think-tank Picordi.com. MANILA - Of the 110 bourg’s P198,500 (2nd), countries reviewed, Picodi. and United States’ P174,000 com said the Philippines’ (3rd), as well as Singapore’s IVANA average salary of P15,200 is P168,900 (5th) at P168,900, 95th – far-off Switzerland’s Alawi P296,200 (1st), Luxem- LOWEST SALARY continued on page 24 You can look but not Nostalgia Manila Metropolitan Theatre 1931 touch How Yassi Pressman turned a Triple Whammy Around assi Press- and feelings of uncertain- man , the ty when the lockdown 25-year- was declared in March. Yold actress “The world has glowed as she changed so much shared how she since the start of the dealt with the pandemic,” Yassi recent death of mused when asked her 90-year- about how she had old father, the YASSI shutdown of on page 26 ABS-CBN Philippines positions itself as the ‘crew PHL is top in Online Sex Abuse change capital of the world’ Darna is Postponed he Philippines is off. The ports of Panila, Capin- tional crew changes soon. PHL as Province of China label denounced trying to posi- pin and Subic Bay have all been It is my hope for the Phil- tion itself as a given the green light to become ippines to become a major inter- Angel Locsin prays for her basher crew change hub, crew change locations. -

Kod-4000 Sort by Title Tagalog Song Num Title Artist Num

KOD-4000 SORT BY TITLE TAGALOG SONG NUM TITLE ARTIST NUM TITLE ARTIST 650761 214 Luke Mejares 650801 A Tear Fell Victor Wood 650762 ( Anong Meron Ang Taong ) Happy Itchyworms 650802 A Wish On Christmas Night Jose Mari Chan 650000 (Ang) Kailangan Ko'y Ikaw Regine Velasquez 650803 A Wit Na Kanta Yoyoy Villame 650763 (He's Somehow Been) A Part Of Me Roselle Nava 650804 Aalis Ka Ba?(Crying Time) Rocky Lazatin 650764 (He's Somehow Been)A Part Of Me Roselle Nava 650805 Aangkin Sa Puso Ko Vina Morales 650765 (Nothing's Gonna Make Me) Change Roselle Nava 650806 Aawitin Ko Na Lang Ariel Rivera 650766 (Nothing's Gonna)Make Me Change Roselle Nava 650807 Abalayan Bingbing Bonoan 650187 (This Song) Dedicated To You Lilet 650808 Abalayan (Ilocano) Bingbing Bonoan 650767 ‘Cha Cha Cha’ Unknown 650809 Abc Tumble Down D Children 650768 100 Years Five For Fighthing 650188 Abot Kamay Orange&Lemons 650769 16 Candles The Crest 650810 Abot Kamay (Mtv) Orange&Lemons 650770 214 (Mtv) Luke Mejares 650189 Abot-Kamay Orange And Lemons 650771 214 (My Favorite Song) Rivermaya 650811 About Kaman Orange&Lemons 650772 2Nd Floor Nina 650812 Adda Pammaneknek Nollie Bareng 650773 2Nd Floor (Mtv) Nina 650813 Adios Mariquita Linda Adapt. L. Celerio 650774 6_8_12 (Mtv) Ogie Alcasid 650814 Adlaw Gai-I Nanog Rivera 650775 9 & Cooky Chua Bakit (Mtv) Gloc 650815 Adore You Eddie Peregrina 650776 A Ba Ka Da Children 650816 Adtoyakon R. Lopez 650777 A Beautiful Sky (Mtv) Lynn Sherman 650817 Aegis Rachel Alejandro 650778 A Better Man Ogie Alcasid 650190 Aegis Medley Aegis 650779 A -

Communication Management Category 1: Internal Communcation List of Winners Title Company Entrant's Name AGORA 2.0 Aboitiz Equity Ventures, Inc

Division 1: Communication Management Category 1: Internal Communcation List of Winners Title Company Entrant's Name AGORA 2.0 Aboitiz Equity Ventures, Inc. Lorenne Alejandrino-Anacta Keep It Simple, Sun Lifers: Gamifying A Simple Language Sun Life Financial Philippines Campaign Donante Aaron Peji Data Defenders: Data Privacy Lessons Made Fun and Sun Life Financial Philippines Engaging For Sun Life Employees Donante Aaron Peji PLDT Group Data Privacy Office Handle With Care Ramon R. Isberto Campaign PLDT Aboitiz Equity Ventures, Inc. (Pilmico Foods Super Conversations with SMA Corporation) Lorenne Alejandrino-Anacta Inside World: Engaging a new generation of Megaworld employees via a dynamic e-newsletter Megaworld Corporation Harold C. Geronimo Harnessing SYKES' Influence from Within to Inspire Beyond Reach Sykes Asia, Incorporated Miragel Jan Gabor ManilaMed's #FeelBetter Campaign Comm&Sense Inc. Aresti Tanglao Category 2: Employee Engagement Title Company Entrant's Name LOVE Grants Resorts World Manila Archie Nicasio a.Lab Aboitiz Equity Ventures, Inc. Lorenne V. Alejandrino CineNRW Maynilad Water Services, Inc Sherwin DC. Mendoza Central NRW Point System Maynilad Water Services, Inc Sherwin DC. Mendoza Leadership with a Heart Megaworld Foundation Dr. Francisco C. Canuto Dare 2B Fit ALLIANZ PNB LIFE INSURANCE, INC. ROSALYN MARTINEZ Category 3: Human Resources and Benefits Communication Title Company Entrant's Name Recruitment in the Social Media Era Manila Electric Company Gavin D. Barfield Category 5: Safety Communication Title Company Entrant's Name Championing cybersecurity awareness Bank of the Philippine Islands (BPI) Owen L. Cammayo Unang Hakbang Para Sa Kaligtasan: 2018 First Working MERALCO - Organizational Safety and Day Safety Campaign Resiliency Office Antonio Abuel Jr. -

Lopez Group Lalong Tatatag Sa Susunod Na 5 Taon

January 2006 Lopez execs bag Excel awards ...p. 6 Lopez Group lalong tatatag sa susunod na 5 taon By Carla Paras-Sison Upang makamit ang katatagan at Media and communications paglago na inaasahan ni OML sa Para sa ABS-CBN Broadcasting “Though there are still daunting envi- susunod na limang taon, idinulog ng Corp., kailangang patatagin ang organ- ronmental imponderables and also ma- Benpres Holdings Corporation sa isasyon, mabawi ang pangunguna sa jor business problems in some of our bawa’t kumpanya ng mga kailangang Mega Manila TV ratings at ipagpatuloy companies, I am optimistic that we are mangyari sa taong 2006. ang paglago ng ABS-CBN Global. making definite progress toward group stability, growth and increased prof- Turn to page 2 Meralco Phase 4 itability in the next five years,” pa- hayag ni LopezGroup chairman Oscar refund ongoing...p. 2 M. Lopez(OML) sa nakaraang Strate- gic Planning Conference. Abangan ang ‘Pinoy Big Brother’ Season 2! ...p. 5 2 LOPEZLINK January 2006 Lopez Group lalong tatatag ... from page 1 Bagama’t nakapaglunsad ng mga mga bagong proyekto para sa strategic ings sa 2006 kung maaprubahan ang Para sa Manila North Tollways Property development bagong programa ang ABS-CBN growth. rate hike na hinihiling ng Meralco. Corp. (MNTC), nakatuon ang pansin Inaasahang mabebenta ng Rockwell noong 2005, hindi pa nito nababawi Sa Sky Cable, inaasahang magawa Walumpu’t dalawang porsiyento sa pagpapadami ng motoristang du- Land Corporation ang 100% ng Joya ang leadership sa Mega Manila TV ang pilot encryption ng Sky Cable ng kita ng First Holdings ay mangga- madaan sa North Luzon Expressway condominium sa taong ito. -

Si Judy Ann Santos at Ang Wika Ng Teleserye 344

Sanchez / Si Judy Ann Santos at ang Wika ng Teleserye 344 SI JUDY ANN SANTOS AT ANG WIKA NG TELESERYE Louie Jon A. Sánchez Ateneo de Manila University [email protected] Abstract The actress Judy Ann Santos boasts of an illustrious and sterling career in Philippine show business, and is widely considered the “queen” of the teleserye, the Filipino soap opera. In the manner of Barthes, this paper explores this queenship, so-called, by way of traversing through Santos’ acting history, which may be read as having founded the language, the grammar of the said televisual dramatic genre. The paper will focus, primarily, on her oeuvre of soap operas, and would consequently delve into her other interventions in film, illustrating not only how her career was shaped by the dramatic genre, pre- and post- EDSA Revolution, but also how she actually interrogated and negotiated with what may be deemed demarcations of her own formulation of the genre. In the end, the paper seeks to carry out the task of generically explicating the teleserye by way of Santos’s oeuvre, establishing a sort of authorship through intermedium perpetration, as well as responding on her own so-called “anxiety of influence” with the esteemed actress Nora Aunor. Keywords aura; iconology; ordinariness; rules of assemblage; teleseries About the Author Louie Jon A. Sánchez is the author of two poetry collections in Filipino, At Sa Tahanan ng Alabok (Manila: U of Santo Tomas Publishing House, 2010), a finalist in the Madrigal Gonzales Prize for Best First Book, and Kung Saan sa Katawan (Manila: U of Santo To- mas Publishing House, 2013), a finalist in the National Book Awards Best Poetry Book in Filipino category; and a book of creative nonfiction, Pagkahaba-haba Man ng Prusisyon: Mga Pagtatapat at Pahayag ng Pananampalataya (Quezon City: U of the Philippines P, forthcoming). -

Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary the Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959)

ISSN: 0041-7149 ISSN: 2619-7987 VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio p. AfricA . UNITAS Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) . VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio P. AfricA since 1922 Indexed in the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America Expressions of Tagalog Imgaginary: The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Copyright @ 2016 Antonio P. Africa & the University of Santo Tomas Photos used in this study were reprinted by permission of Mr. Simon Santos. About the book cover: Cover photo shows the character, Mercedes, played by Rebecca Gonzalez in the 1950 LVN Pictures Production, Mutya ng Pasig, directed by Richard Abelardo. The title of the film was from the title of the famous kundiman composed by the director’s brother, Nicanor Abelardo. Acknowledgement to Simon Santos and Mike de Leon for granting the author permission to use the cover photo; to Simon Santos for permission to use photos inside pages of this study. UNITAS is an international online peer-reviewed open-access journal of advanced research in literature, culture, and society published bi-annually (May and November). -

Fantasy Land Rebel Reformer

Msgr. Gutierrez Spiritual: A Beginning or an End? – p. 10 Zena Babao Lifestyle: The Dance of Marriage – p. 9 Miles Beauchamp Perspectives: Changing Sounds – p. 6 Entertainment Lani Misalucha and guest coming to Pechanga – p. 16 March 20-26, 2015 The original and first Asian Journal in America San Diego’s rst and only Asian Filipino weekly publication and a multi-award winning newspaper! Online+Digital+Print Editions to best serve you! 550 E. 8th St., Ste. 6, National City, San Diego County, CA USA 91950 | Ph 619.474.0588 | [email protected] | Follow us on Twitter @asianjournal | www.asianjournalusa.com 44% of Pinoys oppose passage of BBL —Pulse Asia GMA Network | MANILA, 3/19/2015 — Nearly half of Philippine start-up gets funding Filipinos oppose the passage Fantasy Land of the draft Bangsamoro Basic from Silicon Valley Law, a Pulse Asia poll re- ABS CBN News | MA- Gordon. vealed Thursday. NILA, 3/18/2015- A Philip- The tech start-up gener- Rebel Reformer Based on a survey conduct- pine tech start-up aiming to ated $2 million, said to be the By Simeon G. Silverio, Jr. ed on 1,200 Filipino adults revolutionize job search has largest fund raised by a local Chapter 17 of the book, “Fantasy Land” By Simeon G. Silverio, Jr., Publisher & Editor, earlier this month, 44 percent raised additional funding from start-up so far. Several inves- Asian Journal San Diego, the Original and First Asian Journal in America of the respondents disagreed Silicon Valley investors. tors made this possible, 75% when asked if the BBL should Kalibrr joins other success- of which are foreign-based be passed. -

PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST

TITLE NO ARTIST 22 5050 TAYLOR SWIFT 214 4261 RIVER MAYA ( I LOVE YOU) FOR SENTIMENTALS REASONS SAM COOKEÿ (SITTIN’ ON) THE DOCK OF THE BAY OTIS REDDINGÿ (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY 4284 BRITNEY SPEARS (YOU’VE GOT) THE MAGIC TOUCH THE PLATTERSÿ 19-2000 GORILLAZ 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN 9-1-1 EMERGENCY SONG 1 A BIG HUNK O’ LOVE 2 ELVIS PRESLEY A BOY AND A GIRL IN A LITTLE CANOE 3 A CERTAIN SMILE INTROVOYS A LITTLE BIT 4461 M.Y.M.P. A LOVE SONG FOR NO ONE 4262 JOHN MAYER A LOVE TO LAST A LIFETIME 4 JOSE MARI CHAN A MEDIA LUZ 5 A MILLION THANKS TO YOU PILITA CORRALESÿ A MOTHER’S SONG 6 A SHOOTING STAR (YELLOW) F4ÿ A SONG FOR MAMA BOYZ II MEN A SONG FOR MAMA 4861 BOYZ II MEN A SUMMER PLACE 7 LETTERMAN A SUNDAY KIND OF LOVE ETTA JAMESÿ A TEAR FELL VICTOR WOOD A TEAR FELL 4862 VICTOR WOOD A THOUSAND YEARS 4462 CHRISTINA PERRI A TO Z, COME SING WITH ME 8 A WOMAN’S NEED ARIEL RIVERA A-GOONG WENT THE LITTLE GREEN FROG 13 A-TISKET, A-TASKET 53 ACERCATE MAS 9 OSVALDO FARRES ADAPTATION MAE RIVERA ADIOS MARIQUITA LINDA 10 MARCO A. JIMENEZ AFRAID FOR LOVE TO FADE 11 JOSE MARI CHAN AFTERTHOUGHTS ON A TV SHOW 12 JOSE MARI CHAN AH TELL ME WHY 14 P.D. AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH 4463 DIANA ROSS AIN’T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERSÿ AKING MINAHAL ROCKSTAR 2 AKO ANG NAGTANIM FOLK (MABUHAY SINGERS)ÿ AKO AY IKAW RIN NONOY ZU¥IGAÿ AKO AY MAGHIHINTAY CENON LAGMANÿ AKO AY MAYROONG PUSA AWIT PAMBATAÿ PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST AKO NA LANG ANG LALAYO FREDRICK HERRERA AKO SI SUPERMAN 15 REY VALERA AKO’ Y NAPAPA-UUHH GLADY’S & THE BOXERS AKO’Y ISANG PINOY 16 FLORANTE AKO’Y IYUNG-IYO OGIE ALCASIDÿ AKO’Y NANDIYAN PARA SA’YO 17 MICHAEL V.