Raccoon Rehabilitation: Infectious Disease Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bacterial Diseases (Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Other Publications in Zoonotics and Wildlife Disease Wildlife Disease and Zoonotics December 1999 Bacterial Diseases (Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases) Milton Friend Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zoonoticspub Part of the Veterinary Infectious Diseases Commons Friend, Milton, "Bacterial Diseases (Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases)" (1999). Other Publications in Zoonotics and Wildlife Disease. 12. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zoonoticspub/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Disease and Zoonotics at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Other Publications in Zoonotics and Wildlife Disease by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Section 2 Bacterial Diseases Avian Cholera Tuberculosis Salmonellosis Chlamydiosis Mycoplasmosis Miscellaneous Bacterial Diseases Introduction to Bacterial Diseases 73 Inoculating media for culture of bacteria Photo by Phillip J. Redman Introduction to Bacterial Diseases “Consider the difference in size between some of the very tiniest and the very largest creatures on Earth. A small bacterium weighs as little as 0.00000000001 gram. A blue whale weighs about 100,000,000 grams. Yet a bacterium can kill a whale…Such is the adaptability and versatility of microorganisms as compared with humans and other so-called ‘higher’ organisms, that they will doubtless continue to colonize and alter the face of the Earth long after we and the rest of our cohabitants have left the stage forever. Microbes, not macrobes, rule the world.” (Bernard Dixon) Diseases caused by bacteria are a more common cause of whooping crane population has challenged the survival of mortality in wild birds than are those caused by viruses. -

Molecular Analysis of Carnivore Protoparvovirus Detected in White Blood Cells of Naturally Infected Cats

Balboni et al. BMC Veterinary Research (2018) 14:41 DOI 10.1186/s12917-018-1356-9 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Molecular analysis of carnivore Protoparvovirus detected in white blood cells of naturally infected cats Andrea Balboni1, Francesca Bassi1, Stefano De Arcangeli1, Rosanna Zobba2, Carla Dedola2, Alberto Alberti2 and Mara Battilani1* Abstract Background: Cats are susceptible to feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) and canine parvovirus (CPV) variants 2a, 2b and 2c. Detection of FPV and CPV variants in apparently healthy cats and their persistence in white blood cells (WBC) and other tissues when neutralising antibodies are simultaneously present, suggest that parvovirus may persist long-term in the tissues of cats post-infection without causing clinical signs. The aim of this study was to screen a population of 54 cats from Sardinia (Italy) for the presence of both FPV and CPV DNA within buffy coat samples using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The DNA viral load, genetic diversity, phylogeny and antibody titres against parvoviruses were investigated in the positive cats. Results: Carnivore protoparvovirus 1 DNA was detected in nine cats (16.7%). Viral DNA was reassembled to FPV in four cats and to CPV (CPV-2b and 2c) in four cats; one subject showed an unusually high genetic complexity with mixed infection involving FPV and CPV-2c. Antibodies against parvovirus were detected in all subjects which tested positive to DNA parvoviruses. Conclusions: The identification of FPV and CPV DNA in the WBC of asymptomatic cats, despite the presence of specific antibodies against parvoviruses, and the high genetic heterogeneity detected in one sample, confirmed the relevant epidemiological role of cats in parvovirus infection. -

L'opposizione Tra La Considerazione Morale Degli Animali E L'ecologism

Distinti principi, conseguenze messe a confronto: l’opposizione tra la considerazione morale degli animali e l’ecologismo1 Different principles, compared consequences: the opposition between moral consideration towards animals and ecologism di Oscar Horta [email protected] Traduzione italiana di Susanna Ferrario [email protected] Abstract Biocentrism is the position that considers that morally considerable entities are living beings. However, one of the objections is that if we understand that moral consideration should depend on what is valuable, we would have to conclude that the mere fact of being alive is is not what makes someone morally considerable. Ecocentrism is the position that holds that morally valuable entities are not individuals, but the ecosystems in which they live. In fact, among the positions traditionally defended as ecologists there are serious divergences. Some of them, biocentrists, in particular, can ally themselves with holistic positions such as ecocentrism on certain occasions. 1 Si ripubblica il testo per gentile concessione dell’autore. È possibile visualizzare il testo originale sul sito: https://revistas.uaa.mx/index.php/euphyia/article/view/1358. 150 Balthazar, 1, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.13130/balthazar/13915 ISSN: 2724-3079 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Key-words anthropocentrism, biocentrism, ecocentrism, environmentalism, animal ethics, intervention Introduzione L’ambito di studio conosciuto come etica animale si interroga sulla considerazione morale che dovremmo rivolgere agli esseri animati non umani e sulle conseguenze pratiche di ciò. All’interno di questo campo spiccano le posizioni secondo cui tutti gli esseri senzienti devono essere oggetto di rispetto al di là della propria specie di appartenenza. -

Risk of Disease Spillover from Dogs to Wild Carnivores in Kanha Tiger Reserve, India. Running Head

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/360271; this version posted July 3, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Title: Risk of disease spillover from dogs to wild carnivores in Kanha Tiger Reserve, India. Running head: Disease spillover from dogs to carnivores V. Chaudhary1,3 *, N. Rajput2, A. B. Shrivastav2 & D. W. Tonkyn1,4 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, 29634, USA 2 School of Wildlife Forensic and Health, South Civil Lines, Jabalpur, M. P., India 3 Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32603, USA 4 Department of Biology, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, AR 72204, USA Key words Canine Distemper Virus, Canine Parvovirus, Canine Adeno Virus, Rabies, Tiger, Dog, India, Wildlife disease Correspondence * V. Chaudhary, Newins-Ziegler Hall,1745 McCarty Road, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32611. Email: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/360271; this version posted July 3, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Many mammalian carnivore species have been reduced to small, isolated populations by habitat destruction, fragmentation, poaching, and human conflict. -

Canine Distemper Virus in Asiatic Lions of Gujarat State, India

RESEARCH LETTERS SFTSV RNA at 2.4 × 105 copies/mL in his semen that day. Canine Distemper Virus On day 44, we could no longer detect semen SFTSV RNA, and he was discharged on day 51 after onset (Figure 1). in Asiatic Lions of In this study, SFTSV RNA was detected in semen, and Gujarat State, India SFTSV persisted longer in semen than in serum. It is well known that some viruses, such as Zika virus and Ebola vi- rus, can be sexually transmitted; these viruses have been Devendra T. Mourya, Pragya D. Yadav, detected in semen for a prolonged period after symptom Sreelekshmy Mohandas, R.F. Kadiwar, M.K. Vala, onset (6,7). Thus, we considered the potential risk for sex- Akshay K. Saxena, Anita Shete-Aich, ual transmission of SFTSV. Nivedita Gupta, P. Purushothama, Rima R. Sahay, Compared with that of Zika and Ebola viruses, the clin- Raman R. Gangakhedkar, Shri C.K. Mishra, ical significance of potential sexual transmission of SFTSV Balram Bhargava is unknown. However, this possibility should be taken into Author affiliations: Indian Council of Medical Research, National consideration in sexually active patients with SFTSV. Our Institute of Virology, Pune, India (D.T. Mourya, P.D. Yadav, findings suggest the need for further studies of the genital S. Mohandas, A. Shete-Aich, R.R. Sahay); Sakkarbaug Zoo, fluid of SFTS patients, women as well as men, and counsel- Junagadh, India (R.F. Kadiwar, M.K. Vala); Department of ing regarding sexual behavior for these patients. Principal Chief Conservator of Forest, Gandhinagar (A.K. Saxena, P. -

Parvovirus Infections

EAZWV Transmissible Disease Fact Sheet Sheet No. 46 PARVOVIRUS INFECTIONS ANIMAL TRANS- CLINICAL FATAL TREATMENT PREVENTION GROUP MISSION SIGNS DISEASE ? & CONTROL AFFECTED Felidae, Faecal-oral Diarrhoea, Variable Interferons, In houses Canidae, route faeces are depending on hyperimmun- Procyonidae, pasty, blood the immune sera Mustelidae, flecked to status of the in zoos Ursidae, and haemorrhagic, animal and virus Quarantine for at Viveridae leukopenia, strain least 30 days, lymphopenia, vaccination feline ataxia, canine myocarditis Fact sheet compiled by Last update Kai Frölich, Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, February 2002 Berlin, Germany Fact sheet reviewed by U. Truyen, Tiergesundheitsdienst Bayern e.V, Poing, Germany G. Strauß, Tierpark Berlin, Berlin, Germany Susceptible animal groups Species from six families (Felidae, Canidae, Procyonidae, Mustelidae, Ursidae, and Viveridae) in the order Carnivora are suspected of being susceptible to parvovirus of the FPV subgroup. Also syndromes resembling parvovirus infection have been described in an insectivore and a rodent. Causative organism The feline parvovirus subgroup viruses are unenveloped and contain a single-stranded DNA genome about 5.1 kb. The virus capsids are the primary determinants of host range; differences of only two or three amino acids in three areas on or near the surface determine the ability of CPV and FPV to replicate in dogs or cats or their cultured cells. The amplification of parvovirus DNA sequences intermediate between FPV and CPV from tissues of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Europe suggests that wildlife may have played a role in the interspecies transfer of feline parvovirus subgroup virus to dogs. As currently understood, the FPV subgroup is rooted in FPV, from which mink enteritis virus (MEV) and racoon parvovirus (RPV) isolates are indistinguishable, and blue fox parvovirus (BFPV) is a minor variant. -

Risk of Importing Zoonotic Diseases Through Wildlife Trade, United States Boris I

Risk of Importing Zoonotic Diseases through Wildlife Trade, United States Boris I. Pavlin, Lisa M. Schloegel, and Peter Daszak The United States is the world’s largest wildlife import- vidual animals during 2000–2004 (5). Little disease sur- er, and imported wild animals represent a potential source veillance is conducted for imported animals; quarantine is of zoonotic pathogens. Using data on mammals imported required for only wild birds, primates, and some ungulates during 2000–2005, we assessed their potential to host 27 arriving in the United States, and mandatory testing exists selected risk zoonoses and created a risk assessment for only a few diseases (psittacosis, foot and mouth dis- that could inform policy making for wildlife importation and ease, Newcastle disease, avian infl uenza). Other animals zoonotic disease surveillance. A total of 246,772 mam- mals in 190 genera (68 families) were imported. The most are typically only screened for physical signs of disease, widespread agents of risk zoonoses were rabies virus (in and pathogen testing is delegated to either the US Depart- 78 genera of mammals), Bacillus anthracis (57), Mycobac- ment of Agriculture (for livestock) or the importer (6). terium tuberculosis complex (48), Echinococcus spp. (41), The process of preimport housing and importation often and Leptospira spp. (35). Genera capable of harboring the involves keeping animals at high density and in unnatural greatest number of risk zoonoses were Canis and Felis (14 groupings of species, providing opportunities for cross- each), Rattus (13), Equus (11), and Macaca and Lepus (10 species transmission and amplifi cation of known and un- each). -

Phylogenetic Characterization of Canine Distemper Viruses Detected in Naturally Infected North American Dogs

PHYLOGENETIC CHARACTERIZATION OF CANINE DISTEMPER VIRUSES DETECTED IN NATURALLY INFECTED NORTH AMERICAN DOGS __________________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia _________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science __________________________________________________ by INGRID D. R. PARDO Dr. Steven B. Kleiboeker, Thesis Supervisor May 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express gratitude to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Steven B. Kleiboeker, for this teaching, support and patience during the time I spent in the Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory and Department of Veterinary Pathobiology at the University of Missouri-Columbia. I also extend appreciation to my committee members: Drs. Gayle Johnson, Cynthia Besch-Williford, and Joan Coates for their academic support over the past three years, with a special thanks to Dr. Joan Coates for her extensive guidance during the preparation of this thesis. Additionally, I will like to express my gratitude to Dr. Susan K. Schommer, Mr. Jeff Peters, Ms. Sunny Younger, and Ms. Marilyn Beissenhertz for laboratory and technical support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEGEMENTS……………………………………………………………. ii LIST OF FIGURES ………………………………………………………………….. v LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………. vi ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………... vii I. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………. 1 A. Etiology ……………………………...…………………………………….. 1 B. Epidemiology -

Derived Vaccine Protects Target Aniinals Against a Viral Disease

© 1997 Nature Publishing Group http://www.nature.com/naturebiotechnology RESEARCH • Plant -derived vaccine protects target aniinals against a viral disease Kristian Dalsgaard*, Ase Uttenthal1•2, Tim D. Jones3, Fan Xu3, Andrew Merryweather3, William D.O. Hamilton3, Jan P.M. Langeveld4, Ronald S. Boshuizen4, S0ren Kamstrup, George P. Lomonossoffe, Claudine Porta8, Carmen Vela5, J. Ignacio Casal5, Rob H. Meloen4, and Paul B. Rodgers3 Danish Veterinary Institute for Virus Research, Lindholm, DK-4771 Kalvehave, Denmark. 'Danish Veterinary Laboratory, Biilowsvej 27, DK-1790 Copenhagen V, Denmark. 'Present address: Danish Fur Breeders Association, Langagervej 74, DK-2600 Glostrup, Denmark.'Axis Genetics pie., Babmham, Cambridge CB2 4AZ, UK. 'Institute for Animal Science and Health (ID-DLO), P.O. Box 65 NL-8200 AB, Lelystad, The Netherlands. 'In~enasa, C Hermanos Garcia Noblejas 41-2, E-28037 Madrid, Spain. 'John Innes Centre, Colney Lane, Norwich NR4 lUH, UK. •corresponding author ( e-mail: [email protected]). Received 29 May 1996; accepted 26 December 1996. The successful expression of animal or human virus epitopes on the surface of plant viruses has recently been demonstrated. These chimeric virus particles (CVPs) could represent a cost-effective and safe alternative to conventional animal cell-based vaccines. We report the insertion of oligonucleotides coding for a short linear epitope from the VP2 capsid protein of mink enteritis virus (MEV) into an infec tious cDNA clone of cowpea mosaic virus and the successful expression of the epitope on the surface of CVPs when propagated in the black-eyed bean, Vigna unguiculata. The efficacy of the CVPs was estab lished by the demonstration that one subcutaneous injection of 1 mg of the CVPs in mink conferred pro tection against clinical disease and virtually abolished shedding of virus after challenge with virulent MEV, demonstrating the potential utility of plant CVPs as the basis for vaccine development. -

World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency

Supplemental File S1 for the article “World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency” published in BioScience by William J. Ripple, Christopher Wolf, Thomas M. Newsome, Phoebe Barnard, and William R. Moomaw. Contents: List of countries with scientist signatories (page 1); List of scientist signatories (pages 1-319). List of 153 countries with scientist signatories: Albania; Algeria; American Samoa; Andorra; Argentina; Australia; Austria; Bahamas (the); Bangladesh; Barbados; Belarus; Belgium; Belize; Benin; Bolivia (Plurinational State of); Botswana; Brazil; Brunei Darussalam; Bulgaria; Burkina Faso; Cambodia; Cameroon; Canada; Cayman Islands (the); Chad; Chile; China; Colombia; Congo (the Democratic Republic of the); Congo (the); Costa Rica; Côte d’Ivoire; Croatia; Cuba; Curaçao; Cyprus; Czech Republic (the); Denmark; Dominican Republic (the); Ecuador; Egypt; El Salvador; Estonia; Ethiopia; Faroe Islands (the); Fiji; Finland; France; French Guiana; French Polynesia; Georgia; Germany; Ghana; Greece; Guam; Guatemala; Guyana; Honduras; Hong Kong; Hungary; Iceland; India; Indonesia; Iran (Islamic Republic of); Iraq; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Jamaica; Japan; Jersey; Kazakhstan; Kenya; Kiribati; Korea (the Republic of); Lao People’s Democratic Republic (the); Latvia; Lebanon; Lesotho; Liberia; Liechtenstein; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Macedonia, Republic of (the former Yugoslavia); Madagascar; Malawi; Malaysia; Mali; Malta; Martinique; Mauritius; Mexico; Micronesia (Federated States of); Moldova (the Republic of); Morocco; Mozambique; Namibia; Nepal; -

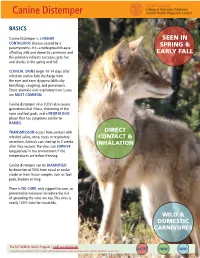

Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) Also Causes Gastrointestinal Illness, Thickening of the Nose and Foot Pads, and a NEUROLOGIC Phase That Has Symptoms Similar to RABIES

Canine Distemper BASICS Canine Distemper is a HIGHLY SEEN IN CONTAGIOUS disease caused by a SPRING & paramyxovirus. It is a widespread disease affecting wild and domestic carnivores and EARLY FALL this primarily infeects raccoons, grey fox and skunks in the spring and fall. CLINICAL SIGNS begin 10-14 days after infection and include discharge from the eyes and nose, dyspnea (difficulty breathing), coughing, and pneumonia. Fever, anorexia and respiratory tract issues are MOST COMMON. Canine distemper virus (CDV) also causes gastrointestinal illness, thickening of the nose and foot pads, and a NEUROLOGIC phase that has symptoms similar to RABIES. TRANSMISSION occurs from contact with DIRECT infected saliva, urine, feces or respiratory CONTACT & secretions. Animals can shed up to 2 weeks INHALATION after they recover. The virus can SURVIVE long periods in the environment if the temperatures are below freezing. Canine distemper can be DIAGNOSED by detection of DNA from nasal or ocular swabs or from tissue samples such as foot pads, bladder or lung. There is NO CURE, only supportive care, so preventative measures to reduce the risk of spreading the virus are key. This virus is nearly 100% fatal for mustelids. WILD & DOMESTIC CARNIVORES The NYS Wildlife Health Program | cwhl.vet.cornell.edu ALERT HOW WHO A partnership between NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation and Cornell Wildlife Health Lab DETAILS The NEUROLOGIC PHASE of the disease affects the The disease is found in canids (domestic dogs, coyotes, central nervous system and can cause disorientation wolves, foxes) as well as raccoons, javelinas, and some and weakness along with progressive seizures. -

Canine Distemper Closely CANINE Resembles Rabies

leading to its nickname “hard pad disease.” For more information, visit: In wildlife, infection with canine distemper closely CANINE resembles rabies. www.avma.org Distemper is often fatal, and dogs that survive usually have permanent, irreparable nervous system damage. DISTEMPER Brought to you by your veterinarian and the American Veterinary Medical Association HOW IS CANINE DISTEMPER DIAGNOSED AND TREATED? Veterinarians diagnose canine distemper through clinical appearance and laboratory testing. There is no cure for canine distemper infection. Treatment typically consists of supportive care and efforts to prevent secondary infections, control vomiting, diarrhea and neurologic symptoms, and combat dehydration through administration of fluids. Dogs infected with canine distemper should be separated from other dogs to minimize the risk of further infection. HOW IS CANINE DISTEMPER PREVENTED? Vaccination is crucial in preventing canine distemper. • A series of vaccinations is administered to puppies to increase the likelihood of building immunity when the immune system has not yet fully matured. • Avoid gaps in the immunization schedule and make sure distemper vaccinations are up to date. • Avoid contact with infected animals and wildlife • Use caution when socializing puppies or unvaccinated dogs at parks, puppy classes, obedience classes, doggy day care and other places where dogs can congregate. • Pet ferrets should be vaccinated against canine distemper using a USDA-approved ferret vaccine. www.avma.org | 800.248.2862 CANINE DISTEMPER is a contagious disease caused by a virus that attacks the respiratory, gastrointestinal and nervous systems of puppies and dogs. The virus can also be found in wildlife such as foxes, wolves, coyotes, raccoons, skunks, mink and ferrets and has been reported in lions, tigers, leopards and other wild cats as well as seals.