Black Greek-Lettered Organizations: How Schools Like ETSU Benefit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech 1923 • On February 10th, Texas Technological College was founded. 1924 • On June 27th, the Board of Directors voted not to allow Greek-lettered organizations on campus. 1925 • Texas Technological College opened its doors. The college consisted of six buildings, and 914 students enrolled. 1926 • Las Chaparritas was the first women’s club on campus and functioned to unite girls of a common interest through association and engaging in social activities. • Sans Souci – another women’s social club – was founded. 1927 • The first master’s degree was offered at Texas Technological College. 1928 • On November 21st, the College Club was founded. 1929 • The Centaur Club was founded and was the first Men’s social club on the campus whose members were all college students. • In October, The Silver Key Fraternity was organized. • In October, the Wranglers fraternity was founded. 1930 • The “Matador Song” was adopted as the school song. • Student organizations had risen to 54 in number – about 1 for every 37 students. o There were three categories of student organizations: . Devoted to academic pursuits, and/or achievements, and career development • Ex. Aggie Club, Pre-Med, and Engineering Club . Special interest organizations • Ex. Debate Club and the East Texas Club . Social Clubs • Las Camaradas was organized. • In the spring, Las Vivarachas club was organized. • On March 2nd, DFD was founded at Texas Technological College. It was the only social organization on the campus with a name and meaning known only to its members. • On March 3rd, The Inter-Club Council was founded, which ultimately divided into the Men’s Inter-Club Council and the Women’s Inter-Club Council. -

A Guide for College & University

PBS-5b | MEMBER 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF ANTI-HAZING PHI BETA SIGMAPOLICY FRATERNITY, AND INC. HOLD HARMLESS AGREEMENT A GUIDE FOR COLLEGE UPDATED: 11/8/2017 & UNIVERSITY OFFICIALS 145 KENNEDY STREET, NW | WASHINGTON, D.C. 20011 www.phibetasigma1914.org www.phibetasigma1914.org TABLE OF CONTENT Message from the President pg3 About Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. pg4 Phi Beta Sigma’s Community Initiatives, Partnerships and Programs pg5 Training, Development and Support pg6 Fraternity Structure pg7 Organizational Flow pg9 Membership Criteria pg10 2 Sigma’s MIP at a glance pg11 Sigma’s Risk Management Policy pg14 2018 Regional Conference Schedule pg49 2017 Fraternity Highlights pg50 Notable Members pg52 Phi Beta Sigma’s Branding Standards pg55 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Campus Partner- It is an honor and a privilege to address you as the 35th International President of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Incorporated! This is an exciting time to be a Sigma, as our Fraternity moves into a new era, as “A Brotherhood of Conscious Men Actively Serving Our Communities.” We are excited about the possibilities of having an even greater impact on your campus as the Men of Sigma march on! We prepared this booklet to provide you a glance into the world of Phi Beta Sigma, our cause and our initiatives. Indeed, we are a brotherhood of conscious men; Conscious Husbands, Conscious Fathers, Conscious Servants, Conscious Leaders, called to improve the lives of the people we touch. Our collegiate Brothers play a major role in achieving our mission, as they are the lifeblood and future of our Fraternity and communities. -

Office of Student Life and Services Greek Letter Organizations The

Office of Student Life and Services Greek Letter Organizations The following organizations are currently a recognized chartered organization on the University campus: Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. – Omicron Omicron Chapter Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. - Beta Lambda Chapter Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. - Beta Kappa Chapter Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. – Omicron Gamma Chapter Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. – Beta Iota Chapter Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. - Gamma Lambda Chapter Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. - Kappa Alpha Chapter Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. – Beta Chapter Iota Phi Theta Fraternity, Inc. - Theta Chapter *National Pan Hellenic Council (NPHC) All active Greek Sororities and Fraternities must be represented on the University Pan Hellenic Council. Students in the organization must be currently enrolled in the University. Membership must consist of a minimum of five (5) students. Members must have a minimum cumulative 2.5 grade point average and be in good standing with the University. *Please be advised that student members are required to adhere to all eligibility criteria determined by Greek-Letter Organization. Each organization must have an advisor approved by the Office of Student Life and Services (advisor must be an employee of the University). Greek-letter organizations are required to have a campus and graduate advisor. Student Activities - August 2012 Each organization must at the beginning of each semester provide to the Office of Student Life and Services: o a membership roster (students’ names, UDC student ID numbers, telephone numbers, addresses and email addresses) o Officers’ roster (President, Vice President, Secretary, Treasurer) o Advisors’ (Campus and Graduate) contact information o Recent copy of the organization's constitution/by-laws, if amended o Current copy of certificate of liability insurance (see Office of Student Life and Services for additional information) Completed registration forms should be submitted to the Office of Student Life and Services. -

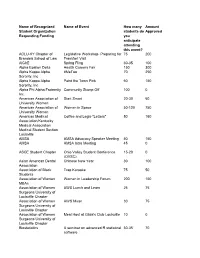

2018 Spring CPC 1St Round Awards

Name of Recognized Name of Event How many Amount Student Organization students do Approved Requesting Funding you anticipate attending this event? ACLU-KY Chapter of Legislative Workshop- Preparing for 75 200 Brandeis School of Law Frankfort Visit AIChE Spring Fling 30-35 100 Alpha Epsilon Delta Health Careers Fair 150 300 Alpha Kappa Alpha #MeToo 70 250 Sorority, Inc Alpha Kappa Alpha Paint the Town Pink 60 150 Sorority, Inc Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Community Stomp Off 100 0 Inc. American Association of Start Smart 20-30 50 University Women American Association of Women in Space 50-120 750 University Women American Medical Coffee and Legis-"Letters" 50 160 Association/Kentucky Medical Association Medical Student Section Louisville AMSA AMSA Advocacy Speaker Meeting 50 150 AMSA AMSA Intro Meeting 45 0 ASCE Student Chapter Ohio Valley Student Conference 15-20 0 (OVSC) Asian American Dental Chinese New Year 30 100 Association Association of Black Trap Karaoke 75 50 Students Association of Women Women in Leadership Forum 200 150 MBAs Association of Women AWS Lunch and Learn 25 75 Surgeons University of Louisville Chapter Association of Women AWS Mixer 30 75 Surgeons University of Louisville Chapter Association of Women Meal Host at Gilda's Club Louisville 10 0 Surgeons University of Louisville Chapter Biostatistics A seminar on advanced R statistical 30-35 70 software Biostatistics Club A seminar on SAS statistical 30-35 70 software Biostatistics Club Careers in Statistics 30-40 0 Black Student Nurses GO Red! Heart Health Fair 50-70 163 -

Fall 2020 Community Grade Report Women's Organizations

Fall 2020 Community Grade Report Women's Organizations Dollars Service Organization Semester Cumulative Donated New Member (Total Members/New Council Hours per GPA** GPA* per Semester GPA ** Members) Member Member Alpha Kappa Alpha NPHC 3.048 3.079 11 - - (31/0) Delta Sigma Theta NPHC 2.965 3.169 - $1.14 FERPA Protected (22/21) Delta Zeta (31/12) PC 3.159 3.358 - - 2.815 Hermanas of N/A 3.318 3.478 - - 2.956 Leadership Assoc. (9/3) Phi Mu (31/9) PC 3.252 3.344 - $19.03 3.332 Sigma Gamma Rho NPHC 2.762 2.729 - - - (10/0) Zeta Phi Beta (3/0) NPHC 3.011 2.995 8.67 $25 - Zeta Tau Alpha (27/10) PC 3.187 3.307 - - 2.923 Men's Organizations Dollars Service Organization Semester Cumulative Donated New Member (Total Members/New Council Hours per GPA ** GPA* per Semester GPA ** Members) Member Member Alpha Phi Alpha (8/0) NPHC 2.734 2.784 1 - - Alpha Sigma Phi (20/0) IFC 3.024 3.096 - - - Kappa Alpha Psi (9/0) NPHC 2.409 2.636 - - - Omega Psi Phi (8/0) NPHC 2.156 2.619 - - - Phi Beta Sigma (9/0) NPHC 2.492 2.848 - - - Sigma Alpha Epsilon IFC 1.725 2.475 - - - (9/0) * For the purpose of this report, Cumulative Grade Point Average (GPA) refers to a student’s GPA from courses completed at USC Upstate and does not include GPAs that transferred from other colleges or universities. ** For categories with fewer than three members, grades are not made public in order to protect the privacy of academic records for those students; however, member grades are included in overall FSL averages. -

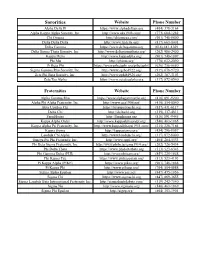

MSU FSL HQ Contacts

Sororities Website Phone Number Alpha Delta Pi https://www.alphadeltapi.org (404) 378-3164 Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. http://www.aka1908.com/ (773) 684-1282 Chi Omega http://chiomega.com/ (901) 748-8600 Delta Delta Delta http://www.tridelta.org/ (817) 663-8001 Delta Gamma https://www.deltagamma.org (614) 481-8169 Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. http://www.deltasigmatheta.org/ (202) 986-2400 Kappa Delta http://www.kappadelta.org/ (901) 748-1897 Phi Mu http://phimu.org/ (770) 632-2090 Pi Beta Phi https://www.pibetaphi.org/pibetaphi/ (636) 256-0680 Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. http://www.sgrho1922.org/ (919) 678-9720 Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. http://www.zphib1920.org/ (202) 387-3103 Zeta Tau Alpha https://www.zetataualpha.org (317) 872-0540 Fraternities Website Phone Number Alpha Gamma Rho https://www.alphagammarho.org (816) 891-9200 Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. http://www.apa1906.net/ (410) 554-0040 Beta Upsilon Chi https://betaupsilonchi.org (817) 431-6117 Delta Chi http://deltachi.org (319) 337-4811 FarmHouse http://farmhouse.org (816) 891-9445 Kappa Alpha Order http://www.kappaalphaorder.org/ (540) 463-1865 Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. http://www.kappaalphapsi1911.com/ (215) 228-7184 Kappa Sigma http://kappasigma.org/ (434) 296-9557 Lambda Chi Alpha http://www.lambdachi.org/ (317) 872-8000 Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. http://www.oppf.org/ (404) 284-5533 Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. http://www.phibetasigma1914.org/ (202) 726-5434 Phi Delta Theta https://www.phideltatheta.org (513) 523-6345 Phi Gamma Delta (FIJI) http://www.phigam.org/ (859) 225-1848 Phi Kappa Tau https://www.phikappatau.org/ (513) 523-4193 Pi Kappa Alpha (PIKE) https://www.pikes.org/ (901) 748-1868 Pi Kappa Phi http://www.pikapp.org/ (704) 504-0888 Sigma Alpha Epsilon http://www.sae.net/ (847) 475-1856 Sigma Chi https://www.sigmachi.org (847) 869-3655 Sigma Lambda Beta International Fraternity, Inc. -

Map of Get Involved Fair

Map of Get Involved Fair A Club Tables Row 1 Row 2 Row 3 Table Club Table Club Table Club 1A SAAC 2A 3A Outing Club 1B Assocation for Commuter Engagement 2B Multicultural Greek Council 3B Alpha Epsilon Pi 1C NTID Student Congress (NSC) 2C College Panhellenic Council 3C RIT Jam 1D Student Government 2D Interfraternity Council 3D Computer Science Community 1E Center for Leadership/Civil Engagement 2E Alpha Phi Alpha 3E SPARSA 1F COLA Advisory Board 2F PiRIT 3F Competitive Cybersecurity Club 1G 2G Sigma Lambda Upsilon 3G Phi Kappa Tau 1H Reporter Magazine 2H Fulbright Scholars Association 3H Space Time Adventures Club 1I Colleges Against Cancer 2I Deaf International Student Association 3I RWAG 1J Global Union 2J Empty Sky Go Club 3J Fantasy Club 1K Air Force ROTC 2K Anime 3K RIT Space Exploration 1L College Activities Board Row 4 Row 5 Row 6 Table Club Table Club Table Club Brick City Boppers Swing Dance 4A 5A 6A International Socialist Org Aikido Kokikai Club Club Society of Hispanic Professional 4B 5B 6B Phi Kappa Psi Engineers Spoken Information 4C Labrys Women's Alliance 5C OASIS 6C Interior Design Club 4D Tangent 5D Organization of African Students 6D Hands of Fire 4E RITGA 5E Asian Culture Society 6E Pool Club 4F Capoeira Angola Quintal 5F Latin Rhythm Dance Club 6F Brothers and Sisters in Christ 4G Cru 5G Latin American Deaf Club 6G Agape Christian Fellowship 4H 5H Lambda Sigma Upsilon Latino Fraternity 6H Taiwanese Culture Association Incorporated Hillel Society of Asian Scientists And 4I 5I 6I Engineers (SASE) Latin American Student -

Race, Sorority, and African American Uplift in the 20Th Century

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 27 Article 5 Number 1 Winter 2016 1-1-2016 Lifting as They Climb: Race, Sorority, and African American Uplift in the 20th eC ntury Gregory S. Parks Caryn Neumann Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Gregory S. Parks and Caryn Neumann, Lifting as They Climb: Race, Sorority, and African American Uplift ni the 20th Century, 27 Hastings Women's L.J. 109 (2016). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol27/iss1/5 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lifting As They Climb: Race, Sorority, and African American Uplift in the 20th Century Gregory S. Parks* and Caryn Neumann** INTRODUCTION In the July 2015 issue of Essence magazine, Donna Owens wrote an intriguing piece on black sororities within the Black Lives Matter Movement. Owens addressed the complicated and somewhat standoffish position of four major black sororities-Alpha Kappa Alpha, Delta Sigma Theta, Zeta Phi Beta, and Sigma Gamma Rho-in light of the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Among them, only Zeta Phi Beta had taken an unwavering stance from the outset to allow their members to wear sorority letters while participating in protests.3 This narrative probably would seem insignificant, except for the following: First, black sororities have a unique structure. -

FSCL PRESIDENTS Spring 2021

FSCL PRESIDENTS Spring 2021 Interfraternity Council Oranization Name Email Acacia Ben Walbaum [email protected] Alpha Chi Rho Andrew Spear [email protected] Alpha Epsilon Pi Roey Kleiman [email protected] Alpha Gamma Rho Levi Logue [email protected] Alpha Sigma Phi Justin Anderson [email protected] Alpha Tau Omega Kiernan McCormick [email protected] Beta Chi Theta Nathan Daniel [email protected] Beta Sigma Psi Richard Howey [email protected] Beta Theta Pi Luke Godfrey and Curtis Martin [email protected] Beta Upsilon Chi Max McClure [email protected] Delta Sigma Phi Andrew Musick [email protected] Delta Tau Delta Ben Bruce [email protected] Evans Scholars Aaron Schwind [email protected] FarmHouse Drew Kelham [email protected] Kappa Alpha Order Alexander Fabisiak [email protected] Kappa Delta Rho Harrison Pavel [email protected] Kappa Sigma Kevin Boes [email protected] Lambda Chi Alpha Nick Hull [email protected] Phi Delta Theta Reese Crowell [email protected] Phi Gamma Delta Alex Paskill [email protected] Phi Kappa Psi AJ Muegge [email protected] Phi Kappa Sigma Hassan Chaudry [email protected] Phi Kappa Tau Isaac Tebben [email protected] Phi Sigma Kappa Chirag Vijay [email protected] Pi Kappa Alpha William Weisbrod [email protected] Pi Kappa Phi John Wagner [email protected] Pi Lambda Phi Kenneth Mayberry [email protected] Psi Upsilon Heather Craker [email protected] -

Fraternity & Sorority Life

FRATERNITY & SORORITY LIFE C A L S T A T E F U L L E R T O N ABOUT FSL Fraternity & Sorority Life at Cal State Fullerton works to create an inclusive learning environment that fosters a sense of belonging and supports values-based development of individuals and communities. Our area provides support, education, and engagement to students as an integral part of the Titan Experience through programming based on the Pillars of Excellence: Brotherhood & Sisterhood, Service & Philanthropy, Leadership, and Scholarship. PILLARS OF THE COMMUNITY FSL STAFF The pillars of Fraternity & Sorority Life consist of values that are shared across all four councils. They are Brotherhood & Sisterhood, Leadership, Scholarship, and Service & Philanthropy. SAMUEL MORALES, M.ED. Assistant Director, Fraternity & Sorority Life [email protected] (he/him/his) JORDAN BIERBOWER, M.S. Coordinator, Fraternity & Sorority Life [email protected] (she/her/hers) ISABELLA FERRANTE Graduate Assistant, Fraternity & Sorority Life [email protected] (she/her/hers) ORGANIZATIONS INTERFRATERNITY COUNCIL Alpha Epsilon Pi Delta Chi Pi Kappa Alpha Pi Kappa Phi Sigma Nu Sigma Pi Tau Kappa Epsilon MULTICULTURAL GREEK COUNCIL Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. Lambda Theta Phi Latin Fraternity, Inc. Sigma Delta Alpha Fraternity, Inc. Sigma Lambda Beta International Fraternity, Inc. Tau Theta Pi Sorority Zeta Phi Rho Fraternity NATIONAL PAN-HELLENIC COUNCIL Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. PANHELLENIC COUNCIL Alpha Chi Omega Alpha Delta Pi Delta Zeta Gamma Phi Beta Sigma Kappa Zeta Tau Alpha Website: fullerton.edu/SLL/FSLife Email: [email protected] Instagram: @CSUFSLL. -

Student Clubs & Organization

CLUBS & ORGANIZATIONS Looking to get more involved on Millersville’s campus? There are over 160 clubs and organizations open to students who want to share their talents, improve upon their professional skills, serve their local and global communities, or meet new people. For more information on each club, visit getinvolved.millersville.edu. • Pre-Law Society ACADEMIC & PROFESSIONAL • Psychology Club • Aesculapian Society [Pre-professional association for health providers] • Public Relations Student Society of America [Pre-professional association] • American Chemical Society • Social Work Organization • American Meteorological Society • Society of Manufacturing Engineers • American Society of Safety Engineers • Society of Motion Picture & Television Engineers • Association of Technology, Management and Applied Engineering • Society of Physics Students • Athletic Training Club • Sociology Club • Biology Club • Spanish Club • Collegiate Middle Level Association [Pre-professional association • STEM Advocates for educators] • Student Alumni Association • Color of Teaching Mentoring Program [Pre-professional association • Student Business Association for educators] • Student PSEA [Pre-professional association for educators] • Computer Science Club • Submersible Research Team • Construction Management Club • Tau Sigma [Transfer Honor Society] • Council for Exceptional Children [Pre-professional association for educators] • Technology and Engineering Education Collegiate Association • Cyber Defense Club • Delta Phi Eta [Academic honors society] -

FRATERNITY and SORORITY CODES Registration Area ASSIGNED CODES for FRATERNITY and SORORITY GRADE POINT AVERAGES 010 – Acacia A

FRATERNITY AND SORORITY CODES Registration Area ASSIGNED CODES FOR FRATERNITY AND SORORITY GRADE POINT AVERAGES 010 – Acacia active 011 – Acacia pledge 020 – Adelante active 021 – Adelante pledge 030 – Alpha Gamma Rho active 031 – Alpha Gamma Rho pledge 040 – Alpha Kappa Lambda active 041 – Alpha Kappa Lambda pledge 050 – Alpha Sigma Phi active 051 – Alpha Sigma Phi pledge 060 – Alpha Tau Omega active 061 – Alpha Tau Omega pledge 070 – Beta Sigma Psi active 071 – Beta Sigma Psi pledge 080 – Beta Theta Pi active 081 – Beta Theta Pi pledge 090 – Delta Chi active 091 – Delta Chi pledge 100 – Delta Sigma Phi active 101 – Delta Sigma Phi pledge 110 – Delta Tau Delta active 111 – Delta Tau Delta pledge 120 – Delta Upsilon active 121 – Delta Upsilon pledge 130 – Farmhouse active 131 – Farmhouse pledge 140 – Kappa Sigma active 141 – Kappa Sigma pledge 150 – Lambda Chi Alpha active 151 – Lambda Chi Alpha pledge 160 – Omega Psi Phi active 161 – Omega Psi Phi pledge 170 – Phi Delta Theta active 171 – Phi Delta Theta pledge 180 – Phi Gamma Delta active 181 – Phi Gamma Delta pledge 190 – Phi Kappa Psi active 191 – Phi Kappa Psi pledge 200 – Phi Kappa Tau active 201 – Phi Kappa Tau pledge 210 – Phi Kappa Theta active 211 – Phi Kappa Theta pledge 220 – Pi Kappa Alpha active 221 – Pi Kappa Alpha pledge 230 – Pi Kappa Phi active 231 – Pi Kappa Phi pledge 240 – Sigma Alpha Epsilon active 241 – Sigma Alpha Epsilon pledge 250 – Sigma Chi active 251 – Sigma Chi pledge 260 – Sigma Nu active 261 – Sigma Nu pledge 270 – Sigma Phi Epsilon active 271 – Sigma Phi