Infrastructure Delivery: the DCO Process in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

K45: Full Chain Public and Stakeholder Engagement Commercial; Project Management

January 2016 K45: Full chain public and stakeholder engagement Commercial; Project Management K45: Full chain public and stakeholder engagement IMPORTANT NOTICE The information provided further to UK CCS Commercialisation Programme (the Competition) set out herein (the Information) has been prepared by Capture Power Limited and its sub-contractors (the Consortium) solely for the Department of Energy and Climate Change in connection with the Competition. The Information does not amount to advice on CCS technology or any CCS engineering, commercial, financial, regulatory, legal or other solutions on which any reliance should be placed. Accordingly, no member of the Consortium makes (and the UK Government does not make) any representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of any of the Information and no reliance may be placed on the Information. In so far as permitted by law, no member of the Consortium or any company in the same group as any member of the Consortium or their respective officers, employees or agents accepts (and the UK Government does not accept) any responsibility or liability of any kind, whether for negligence or any other reason, for any damage or loss arising from any use of or any reliance placed on the Information or any subsequent communication of the Information. Each person to whom the Information is made available must make their own independent assessment of the Information after making such investigation and taking professional technical, engineering, commercial, regulatory, financial, legal or other advice, as they deem necessary. The contents of this report draw on work partly funded under the European Union’s European Energy Programme for Recovery. -

Planning and Permitting Study UK (July 2019)

NORTH SEA WIND POWER HUB CONSORTIUM Planning and Permitting Study Final Report P2303_R4682_Rev3 | 1 July 2019 Intertek Energy & Water Consultancy Services Exchange House, Station Road, Liphook, Hampshire GU30 7DW, United Kingdom North Sea Wind Power Hub Consortium Planning and Permitting Study Final Report DOCUMENT RELEASE FORM North Sea Wind Power Hub Consortium P2303_R4682_Rev3 Planning and Permitting Study Final Report Author/s Charlie Cameron, Jillian Hobbs Project Manager Authoriser Emma Langley Beth Monkman Rev No Date Reason Author Checker Authoriser Rev 0 25/04/2019 Draft Section 1 & 2 CC JH BHM Rev 1 10/05/2019 Draft Section 3 CC JH BHM Rev 2 24/05/2019 Final Draft CC JH / ESL BHM Rev 3 01/07/2019 Final CC ESL BHM Intertek Energy & Water Consultancy Services is the trading name of Metoc Ltd, a member of the Intertek group of companies. I P2303_R4682_Rev3 | 1 July 2019 North Sea Wind Power Hub Consortium Planning and Permitting Study Final Report CONTENTS DOCUMENT RELEASE FORM I GLOSSARY IV 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Project Overview 1 1.2 Study Objectives 1 1.3 Scope of Work 2 2. SUMMARY OF APPLICABLE LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 4 2.1 International and European Policy and Legislation 4 2.2 National Policy and Legislation 10 2.3 Current Status of Hydrogen Transmission in the UK 19 3. UK PLANNING AND PERMITTING REQUIREMENTS 20 3.1 Planning Considerations 20 3.2 Consents Required for OWF and Interconnector Cables 31 4. KEY PLANNING AND PERMITTING ISSUES 54 4.1 Consultation 54 4.2 Key Issues 57 5. PROJECT PROPOSED TIMELINES 59 6. -

SIMPLIFIED PLANNING Planning Regulations, in Particular, Remain Notoriously Complex

In common with all recent Governments, the Coalition has often declared its ambition to “cut red tape”. Yet only modest gains have been achieved. SIMPLIFIED PLANNING Planning regulations, in particular, remain notoriously complex. 118 Acts combine to create a “lawyer’s banquet” of complexity. The result is an unnecessarily lengthy and costly planning procedure which enables vested interests to prosper, Simplifi ed planning creates commercial uncertainty and restricts new development. The renewed interest in Garden Cities is to be welcomed. Applying the lessons of The case for sunset clauses the success of Milton Keynes (and that of the Urban Development Corporations) could lead to a new era of privately-fi nanced Garden Cities, thereby easing the current housing shortage while also spurring growth. KEITH BOYFIELD AND INNA ALI The fi rst step must be to rationalise all planning regulation in a New Consolidated Act.; and to introduce sunset clauses for all new planning regulations. KEITH BOYFIELD AND INNA ALI KEITH BOYFIELD Price £10.00 Centre Centre for Policy for Policy Studies Studies THE AUTHORS Keith Boyfield is a Research Fellow of the Centre for Policy Studies. He advises a range of companies, non-profit organisations, inter-governmental bodies and media groups. He edited and contributed to Britain's Unsolved Housing Dilemma published by the European Policy Forum. Inna Ali holds a LL B from Essex University and a Master in Laws (LLM) from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, where she was awarded a Merit for her dissertation on Law. She is currently studying for a Masters in management at BPP University College, London. -

Planning Act 2008: Consultation on Examination Procedures for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects

Planning Act 2008: consultation on examination procedures for nationally significant infrastructure projects www.communities.gov.uk community, opportunity, prosperity Planning Act 2008: consultation on examination procedures for nationally significant infrastructure projects July 2009 Department for Communities and Local Government: London Department for Communities and Local Government Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone: 020 7944 4400 Website: www.communities.gov.uk © Crown Copyright, 2009 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. This publication, excluding logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. Any other use of the contents of this publication would require a copyright licence. Please apply for a Click-Use Licence for core material at www.opsi. gov.uk/click-use/system/online/pLogin.asp, or by writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU e-mail: [email protected] If you require this publication in an alternative format please email [email protected] Communities and Local Government Publications Tel: 0300 123 1124 Fax: 0300 123 1125 Email: [email protected] Online via the Communities and Local Government website: -

Hornsea Project Four: Preliminary Environmental Information Report (PEIR)

Hornsea Project Four: Preliminary Environmental Information Report (PEIR) Volume 1, Chapter 2: Planning and Policy Context Prepared Royal HaskoningDHV, June 2019 Checked Pinsent Masons, June 2019 Accepted Rachel Hall, Orsted, June 2019 Approved Julian Carolan, Orsted 30 July 2019 A 1.2 Version A Table of Contents 2.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6 2.1.2 Requirement for Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) .......................... 6 2.2 International Policy and Context ....................................................................................... 7 2.2.1 International Climate Change and Renewable Energy Policy and Legislation ................................................................................................................ 7 2.2.2 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change ..................... 8 2.2.3 European Union Renewables Directive / Renewable Energy Directive ................................................................................................................... 9 2.2.4 International Environmental and Nature Conservation Legislation and Treaties ........................................................................................................... 10 2.3 National Planning and Legislative Context ................................................................... 13 2.3.1 The Planning Act (2008) .................................................................................... -

Swale Renewable Energy & Sustainable Development Study

Design + Planning Building Engineering Swale Renewable Energy & Sustainable Development Study Prepared for Swale Borough Council November 2011 SWALE LDF EVIDENCE BASE – RENEWABLE ENERGY AND LOW CARBON DEVELOPMENT |i Executive Summary STUDY OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE Swale Borough Council appointed AECOM to develop a climate change, sustainable construction and renewable energy evidence base to inform the development of relevant Core Strategy policies and supporting documents for the Authority. The objectives of this study were to: Understand current and future carbon profile for the Borough Identify carbon reduction and renewable energy opportunities Help set appropriate policy and targets where appropriate Consider full sustainable design and construction standards Enable mechanisms for delivery The focus of the study will be set out how the Core Strategy can be delivered in a more sustainable, carbon efficient way, which meets the requirements of PPS1, specifically: “Planning authorities should have an evidence‐based understanding of the local feasibility and potential for renewable and low carbon technologies, including micro‐generation, to supply new development in their area.” Analysing Swale’s policy direction, and physical and delivery context provided us with the necessary understanding of the Borough’s current circumstances and expected growth scenarios. Armed with this knowledge, we have identified the locally specific needs for policies and actions as outlined in the diagram below. Figure E1: Policy development Process i SWALE LDF EVIDENCE BASE – RENEWABLE ENERGY AND LOW CARBON DEVELOPMENT |ii ENERGY DEMAND FROM THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT The spatial analysis in the figures below shows areas where energy use per home is greater than the South East average. Focus on these areas should be given to these areas when applying improvements. -

Building Britain's Future

Introduction: Today’s Britain June 2009 Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty June 2009 CM7654 £26.60 This paper outlines the action that the UK Government is taking to move the UK from recession to recovery and forge a new model of economic growth; restore trust and accountability to the political system through democratic reform and renewal; and modernise our public services and national infrastructure. Much of the work outlined applies across the UK, in those policy areas where Government’s responsibilities extend across England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. However, many other aspects of policy highlighted in the document are devolved, in differing settlements, to the administrations in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. It is the benefit of devolution that the Devolved Administrations can tailor their policies and thus deliver public services to meet the specific needs of their countries. Government and the Devolved Administrations will continue to work closely together to build a more prosperous, stronger, fairer UK, whilst recognising their particular and varying responsibilities. © Crown Copyright 2009 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will -

The Planning Act 2008 Burbo Bank Extension Offshore Wind Farm

The Planning Act 2008 Burbo Bank Extension Offshore Wind Farm Examining Authority’s Report of Findings and Conclusions and Recommendation to the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change _______________________________________ Rynd Smith LLB MA MRTPI FRSA Examining Authority Date: 26 June 2014 Report to the Secretary of State 1 This page intentionally left blank Report to the Secretary of State 1 The Examining Authority's findings, conclusions and recommendation in respect of an application by DONG Energy Burbo Extension (UK) Ltd. for an Order Granting Development Consent for the Burbo Bank Extension Offshore Wind Farm. File Ref EN010026 The application, dated 22 March 2013, was made under section 37 of the Planning Act 2008 (as amended). The applicant is DONG Energy Burbo Extension (UK) Ltd. The application was submitted to the Planning Inspectorate on 22 March 2013. It was accepted for examination on 19 April 2013. The examination of the application began on 26 September 2013 and was completed on 26 March 2014. The application site is located in Liverpool Bay, some 12 km offshore from Point of Ayr (Flintshire / Sir y Fflint, Wales), 7 - 11 km from the north coast of the Wirral peninsula (Wirral, Merseyside) and 8.5 km from Crosby beach (Sefton, Merseyside). The application site adjoins the south- western boundary of the constructed and operational Burbo Bank Offshore Wind Farm. The development proposed comprises the construction and operation of the Burbo Bank Extension Offshore Wind Farm, with up to 69 wind turbine generators and associated offshore infrastructure with a maximum installed capacity (as amended) of 259 MW in an offshore array over a sea area extending to some 40 km2. -

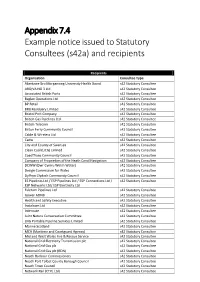

Appendix 7.4 Example Notice Issued to Statutory Consultees (S42a) and Recipients

Appendix 7.4 Example notice issued to Statutory Consultees (s42a) and recipients Recipients Organisation Consultee Type Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board s42 Statutory Consultee ARQIVA NO 3 Ltd s42 Statutory Consultee Associated British Ports s42 Statutory Consultee Baglan Operations Ltd s42 Statutory Consultee BP Retail s42 Statutory Consultee BRB Residuary Limited s42 Statutory Consultee Bristol Port Company s42 Statutory Consultee British Gas Pipelines Ltd s42 Statutory Consultee British Telecom s42 Statutory Consultee Briton Ferry Community Council s42 Statutory Consultee Cable & Wireless Ltd s42 Statutory Consultee Cadw s42 Statutory Consultee City and County of Swansea s42 Statutory Consultee Clean Coal (UCG) Limited s42 Statutory Consultee Coedffranc Community Council s42 Statutory Consultee Company of Proprietors of the Neath Canal Navigation s42 Statutory Consultee DCWW (Dwr Cymru Welsh Water) s42 Statutory Consultee Design Commission for Wales s42 Statutory Consultee Dyffryn Clydach Community Council s42 Statutory Consultee ES Pipelines Ltd / ESP Pipelines Ltd / ESP Connections Ltd / s42 Statutory Consultee ESP Networks Ltd/ ESP Electricity Ltd Fulcrum Pipelines Ltd s42 Statutory Consultee Gower AONB s42 Statutory Consultee Health and Safety Executive s42 Statutory Consultee Instalcom Ltd s42 Statutory Consultee Interoute s42 Statutory Consultee Joint Nature Conservation Committee s42 Statutory Consultee LNG Portable Pipeline Services Limited s42 Statutory Consultee Marine Scotland s42 Statutory Consultee MCA (Maritime -

Environmental Assessment from an Environmental Justice Perspective: Analysing the Impacts of Major Urban Projects in Brazil

University College London Environmental Assessment from an Environmental Justice Perspective: Analysing the Impacts of Major Urban Projects in Brazil Larissa Verri Boratti A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Laws of University College London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London, September 2016 Declaration I, Larissa Verri Boratti, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ii" " Abstract Major urban projects associated with sporting mega-events have set the tone for the urban agenda of local governments in Brazil since the country was announced as the host of FIFA’s Football World Cup 2014 and the Olympics 2016. Development consent for these projects is at the core of rising urban-environmental conflicts over development goals and the uneven distribution of costs and benefits of urbanization. Environmental assessment (EA) operating within this political and developmental agenda plays a central role. EA governs the gathering of information, predicting impacts, defining and calculating mitigating and compensatory measures and engaging publics in decision-making, and in carrying out each of these aspects it may produce or reinforce distributional effects. In light of this, this thesis explores the extent to which the regulatory regime and practice of project-level EA can assist in securing environmental justice, particularly when operating within the planning control process for major urban projects in specific and local socio-political contexts. The thesis offers insights into both theory (Part I) and practice (Part II) of EA in terms of the degree to which it is able to incorporate the different dimensions of environmental justice. -

Planning for Climate Change

Planning for Climate Change A Guide for Local Authorities ‘There is no task that is more urgent, more compelling or more sacred than that of protecting the climate of our planet for our children and grandchildren.’ Christiana Figueres Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2010-16 Supported by Planning for Climate Change – A Guide for Local Authorities © TCPA. May 2018 Town and Country Planning Association Royal Town Planning Institute 17 Carlton House Terrace 41 Botolph Lane London SW1Y 5AS London EC3R 8DL +44 (0)20 7930 8903 +44 (0)20 7929 9494 [email protected] [email protected] www.tcpa.org.uk www.rtpi.org.uk/ This guide is a living, web-based document and will be updated after the final version of the revised National Planning Policy Framework is published later in 2018. Anyone reading a hard copy should check the TCPA and RTPI websites for updates to the guide. Supported by: BRE, Floodline Consulting, the EPICURO project Endorsed by: CIWEM, Landscape Institute, RSPB, Third Revolution Projects Planning for Climate Change A Guide for Local Authorities Contents 2 Acknowledgements 3 Forewords 4 Who this guide is for? ● Why is this guide being published now? ● The status of this guide ● What this guide does not do 5 Section 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Climate justice 6 1.2 Local action 6 1.3 Planning for the fourth Industrial Revolution 7 1.4 The economic opportunity 7 1.5 How will this guide respond to changes in the revised NPPF? 9 Section 2 Background 9 2.1 The impact of planning reform 9 2.2 The -

National Policy Statement for Geological Disposal Infrastructure a Framework Document for Planning Decisions on Nationally Significant Infrastructure

National Policy Statement for Geological Disposal Infrastructure A framework document for planning decisions on nationally significant infrastructure Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Planning Act 2008 July 2019 National Policy Statement for Geological Disposal Infrastructure A framework document for planning decisions on nationally significant infrastructure Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 9(8) of the Planning Act 2008 July 2019 © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available on our website at: www.gov.uk/official-documents Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-1088-9 CCS0219701904 06/19 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Contents 1. Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 7 1.1 Introduction _________________________________________________________ 7 1.2 Purpose ____________________________________________________________ 7 1.3 Infrastructure covered by this NPS ______________________________________ 10 1.4 Territorial Extent ____________________________________________________