Author Report No Available from Journal Cit Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 CHOIR STATE CHAMPIONSHIPS May 4‐6, 2017 Bauman Auditorium, George Fox University 414 N Meridian Street, Newberg, OR 97132

WITH EVERY PASSENGER & LIGHT TRUCK TIRE PURCHASE Whatever the road throws at you, from potholes to nails — any road hazard, our FREE GUARANTEE protects you 107 Oregon locations to serve you! Over 455 stores throughout the West • www.LesSchwab.com TIRES • BRAKES • SHOCKS • ALIGNMENTS • WHEELS • SUSPENSIONS • BATTERIES OSAA / U.S. BANK / LES SCHWAB TIRES STATE CHAMPIONSHIPS Welcome! Welcome to the OSAA / U.S. Bank / Les On behalf of U.S. Bank, welcome to today's Schwab Tires State Championships! Oregon School Activities Association state Whether students are shooting for the hoop, championship! singing in the choir, marching in time or At the OSAA we believe high school activities aiming for the end zone, they are practicing provide opportunities for young people to We believe in building strong communities skills that will serve them well in school, on receive a well‐rounded education that where we live and work. One way we the job and in life. challenges both mind and body. These demonstrate this commitment in Oregon is opportunities enrich and expand our by supporting OSAA programs, which Today, throughout the state there are 290 students’ school experience and help them promote leadership, teamwork and high schools serving over 180,000 students. become contributing members of society. sportsmanship in young people. Since 1984, These schools help provide valuable U.S. Bank has been proud to support the education for our youth both in and outside Participation in activities teaches students OSAA and its 290 member schools, with more the classroom to help make Oregon a better how to be part of a team; the meaning of than four million dollars in contributions to place to live. -

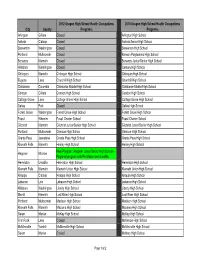

Oregon Public High Schools with Health Science Career Programs 2012

2012 Oregon High School Health Occupations 2010 Oregon High School Health Occupations City County Programs Programs Arlington Gilliam Closed Arlington High School Astoria Clatsop Closed Astoria Senior High School Beaverton Washington Closed Beaverton High School Portland Multnomah Closed Benson Polytechnic High School Bonanza Klamath Closed Bonanza Junior/Senior High School Hillsboro Washington Closed Century High School Chiloquin Klamath Chiloquin High School Chiloquin High School Eugene Lane Churchill High School Churchill High School Clatskanie Colombia Clatskanie Middle/High School Clatskanie Middle/High School Condon Gilliam Condon High School Condon High School Cottage Grove Lane Cottage Grove High School Cottage Grove High School Dallas Polk Closed Dallas High School Forest Grove Washington Forest Grove High School Forest Grove High School Fossil Wheeler Fossil Charter School Fossil Charter School Gilchrist Klamath Gilchrist Junior/Senior High School Gilchrist Junior/Senior High School Portland Multnomah Glencoe High School Glencoe High School Grants Pass Josephine Grants Pass High School Grants Pass High School Klamath Falls Klamath Henley High School Henley High School New Program: Heppner Junior/Senior High School - Heppner Morrow Regional program with Pendleton and Umatilla Hermiston Umatilla Hermiston High School Hermiston High School Klamath Falls Klamath Klamath Union High School Klamath Union High School Knappa Clatsop Knappa High School Knappa High School Lebanon Linn Lebanon High School Lebanon High School Hillsboro Washington -

Eligible High Schools 2019-2020

Eligible High Schools - OR & WA Aloha High School Grant High School Parkrose High School Union High School Amity High School Gresham High School Perrydale High School Vancouver Flex Academy Banks High School Health and Science School Philomath High School Vernonia High School Battle Ground High School Henrietta Lacks (HeLa) High School Pleasant Hill High School Wahkiakum High School Beaverton High School Heritage High School Prairie High School Washougal High School Benson High School Hillsboro High School Putnam High School West Albany High School Camas High School Hockinson High School R.A. Long High School West Linn High School Canby High School Hudson's Bay High School Rainier Jr/Sr High School West Salem High School Cascade High School Jefferson High School Reynolds High School Westview High School Castle Rock High School Jefferson High School (PPS) Ridgefield High School Willamette High School Centennial High School John F. Kennedy High School Riverdale High School Willamina High School Central High School Junction City High School Roosevelt High School Wilson High School Century High School Kalama High School Rosemary Anderson High School Wilsonville High School Churchill High School Kalapuya High School Sam Barlow High School Winlock Senior High School Clackamas High School Kelso High School Sandy High School Woodburn High School Clatskanie Middle High School La Center High School Santiam High School Woodland High School Cleveland High School Lake Oswego High School Scappoose High School Yamhill-Carlton High School Colton High -

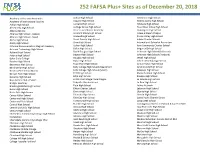

Schools and Organizations Currently Participating in FAFSA Plus+

252 FAFSA Plus+ Sites as of December 20, 2018 Academy of Arts and Academics Colton High School Hermiston High School Academy of International Studies Coquille High School Hidden Valley High School Adrian High School Corvallis High School Hillsboro High School Al Kennedy High School Cottage Grove High School Hood River Valley High School Albany Options Crater Lake Charter Academy Huntington High School Alliance High School - Benson Crescent Valley High School I Have a Dream Oregon Alliance High School - Meek Creswell High School Illinois Valley High School Aloha High School Crook County High School Imbler Charter Schools Amity High School Crow High School International School of Beaverton Arts and Communication Magnet Academy Culver High School Ione Community Charter School Arts and Technology High School Dallas High School Irrigon Jr/Sr High School Ashland High School David Douglas High School Jefferson High School (Jefferson) Astoria High School Dayton High School Jefferson High School (Portland) Baker Early College Douglas High School Jewell High School Bandon High School Dufur High School John F. Kennedy High School Beaverton High School Eagle Point High School Jordan Valley High School Bend Senior High School Early College High School (Beaverton) Junction City High School Bend-La Pine School District Early College High School (Salem) Kalapuya High School Benson Tech High School ECCO High School Klamath Union High School Bonanza High School Echo High School Knappa High School Boys & Girls Club of Salem ECMC-The College Place Oregon -

Serving Career and Technical Education Students in Oregon

Career and Technical Student Organizations Serving Career and Technical Education Students in Oregon 1 Career and Technical Education (CTE) is helping our nation address key challenges such as workforce development, student achievement, economic vitality and global competitiveness. Career and Technical Student Organizations (CTSOs) are key components to strong CTE programs. CTSOs integrate into CTE programs and courses and extend teaching and learning through innovative programs, business and community partnerships and leadership experiences at the school, state and national levels. • CTSOs provide relevant, engaging programs that improve student achievement, reduce dropout rates and help students discover the wide range of career options available. • CTSOs engage the community and local businesses to help students understand global competition and chart effective and efficient pathways through high school and postsecondary education for their personal success. • CTSO programs, such as industry based competitive events and community service, provide students with the opportunity to develop 21st Century Skills focused on creativity, problem solving, teamwork and goal setting. • CTSOs bring relevance to the classroom and prepare students to be college and career ready. The impact that CTSOs make in our state is quite astonishing. We invite you to review this publication to see how Career and Technical Student Organizations are contributing to learning that works in our state. 2 Oregon Fact Sheet CTE STATE OVERVIEW At the secondary level, -

Graduates and Dropouts in Oregon High Schools 2002-03

GRADUATES AND DROPOUTS IN OREGON HIGH SCHOOLS 2002-03 Oregon Department of Education Office of Policy and Research GRADUATES AND DROPOUTS IN OREGON HIGH SCHOOLS 2002-03 Bob Jones Office of Policy and Research Susan Castillo State Superintendent of Public Instruction Oregon Department of Education 255 Capitol Street NE Salem, OR 97310-1300 Complimentary copies have been distributed. Additional copies are available for downloading at http://www.ode.state.or.us/sfda/reports/dropout.htm Please share this document with your colleagues! All or any part of this document may be photocopied for educational purposes without permission from the Oregon Department of Education. It is the policy of the State Board of Education and a priority of the Oregon Department of Education that there will be no discrimination or harassment on the grounds of race, color, sex, marital status, religion, national origin, age or disability in any educational programs, activities or employment. Persons having questions about equal opportunity and nondiscrimination should contact the State Superintendent of Public Instruction at the Oregon Department of Education. Acknowledgements Many individuals made substantial contributions to the preparation of this report. This report was prepared under the direction of Rob Larson, Director of the Office of Policy and Research, Oregon Department of Education. Graduation and dropout data are collected by the Technology & Information Resource Management section. Chris Edison was an invaluable intermediary between the data and the author. The report was reviewed by EJ Ayers, Cliff Brush, Bruce Bull, Linda Burgin, Rob Larson, and John Lenssen. Their efforts and comments are greatly appreciated. Any remaining flaws are the responsibility of the author. -

COVID-19 Weekly Outbreak Report

COVID-19 Weekly Report Oregon’s Weekly Surveillance Summary Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Kindergarten-12th Grade School Report OHA is publishing data on COVID-19 cases associated with schools that offer in-person instruction. This is to inform the public of potential COVID-19 exposure and to provide transparency surrounding COVID-19 in schools. School is defined as any place of learning for students from kindergarten through twelfth grade, or a subset, with at least 30 students enrolled. This includes, but is not limited to, public schools, private schools, parochial and charter schools. Staff is defined as any person who works full time or part-time at the school, regardless of their position. A volunteer is defined as any person who volunteers onsite. Cases are reported if they worked or attended school (either for class or other activities like a sports practice) during their exposure or infectious period. Table 7 below includes all schools that have 1 or more cases of COVID-19 in students or staff/volunteers where the most recent onset occurred within the past 28 days. Schools that have 1 or more cases of COVID-19 in students or staff/volunteers where the most recent onset occurred more than 28 days ago will be moved to a separate table (Table 8). Data are provisional and subject to change 58 COVID-19 Weekly Report Oregon’s Weekly Surveillance Summary Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Table 7. Recent cases Schools with recent COVID-19 Cases (n=242) Staff/ Most recent School Name -

2015 OREGON STATE FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE 1 #Gobeavs 2015

TTABLEABLE OFOF CONTENTSCONTENTS 2015 OREGON STATE FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS . 1 THE COACHES . .80-89 BOWL GAME HISTORY . .185-200 ON THE COVER - Front: Storm Woods, Gary Andersen . .80-83 Josh Mitchell and Larry Scott. Inside MEDIA INFORMATION . 2-7 PLAYER ACCOLADES . .201-208 Assistant Coaches . .84-95 Gary Andersen. Val- Communications Staff Info . 2 Front: Inside Back: Support Staff . 96-101 ALL-AMERICANS . .209-216 ley Football Center renderings. Se- Future Schedules . 2 Back: niors. Media/Credential Information . 3 2014 REVIEW . 102-123 TERRY BAKER SALUTE . .217 Television/Radio Info . 4 Season Statistics . 102-111 Content by Steve Fenk and Ja- BEAVERS IN THE PROS . .218-225 CREDITS: Beaver Sports Radio Network . 5 Game Summaries . .112-123 son Amberg. OSU Social Media . 5 LETTERWINNERS LIST . 226-232 LETTERWINNERS LOST . 124-137 Layout and design by Jason Amberg. Department Contact Info . .6 BEYOND FOOTBALL . 233 Quick Facts . 7 RECORDS . 138-165 Editing by Steve Fenk and Jason Amberg. Individual Records . 138-154 RESER STADIUM / Pronunciation Guide . 7 Cover design by Ben Little. Reser Stadium Records . .155 FACILITIES . 234-235 2015 ROSTERS . 8-11 Team Records . .156-159 Printing by Lynx Group, Inc. in Salem, Ore. Alphabetical Roster . 8-9 ADMINISTRATION . 236-238 Opponent Records . 160 Numerical Roster . 8-9 Special thanks to Kip Carlson, Hal Cowan, Bowl Records . .161-163 PAC-12 STORY . 239 Roster Breakdowns . 10-11 Michelle Woodard, Cindy Arbelbide, Matt All-Time Coaching Records . .164 COMPOSITE PAC-12 Derhalli, Caleb Hawley, Ryan McCall, Lau- PLAYER PROFILES . .12-79 Attendance Records . .165 SCHEDULE / STANDINGS . 240 ren Pullen, Nathan Sarles, Derek Senger, Returning Players . -

OSAA Spirit Safety Training Course Completions 671 Records, Updated 9/30/2021 4:36Pm

OSAA Spirit Safety Training Course Completions 671 Records, Updated 9/30/2021 4:36pm Name School/Organization Role Course Completed Lilliyn Zottola Baguio Adrienne C Nelson High School Dance Coach Dance Specific 9/2/2021 Debi Lazarev Adrienne C. Nelson Dance Coach Dance Specific 8/12/2021 Alma Lopez Adrienne C. Nelson High School Head Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/12/2021 Katie Suh Adrienne C. Nelson High School Assistant Dance Coach Dance Specific 8/15/2021 Alexis Kanalz Adrienne Nelson High School Assistant Cheer Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/16/2021 Sarah Hillyard AGILE Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/23/2021 Chelsea Dunlap Aloha High School Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/13/2021 Kirsten Tankersley Aloha High School Program Advisor Cheerleading Specific 8/11/2021 Mya Santoya Aloha High School Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/13/2021 Chelsea Ochoa Aloha Youth Cheer Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/22/2021 Jamie Story Aloha youth cheer Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/27/2021 Jennifer Bradford Aloha Youth Cheer Assistant Coach Cheerleading Specific 9/7/2021 Lori Dunkelberg Aloha Youth Cheer Board Member Cheerleading Specific 8/26/2021 Renee Stone Aloha Youth Cheer Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/25/2021 Tamara Mitcham Aloha Youth Cheer Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/23/2021 Syndie Rider Amity Head Coach Dance Specific 8/16/2021 Emily Madsen Astoria High School Head Coach Dance Specific 8/19/2021 Savannah Osadchey Astoria High School Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/28/2021 Kendra Gonzales Baker High School Head Coach Cheerleading Specific 8/15/2021 Jordan -

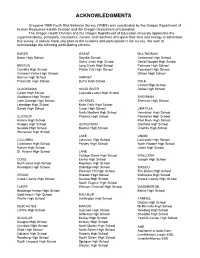

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Oregon=s 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) was coordinated by the Oregon Department of Human Resources= Health Division and the Oregon Department of Education. The Oregon Health Division and the Oregon Department of Education sincerely appreciate the superintendents, principals, counselors, nurses, and teachers who gave their time and energy to administer this survey. A special thank you goes to the students who participated in the survey. We wish to acknowledge the following participating schools: BAKER GRANT MULTNOMAH Baker High School Dayville School Centennial High School Grant Union High School David Douglas High School BENTON Long Creek High School Parkrose High School Corvallis High School Prairie City High School Roosevelt High School Crescent Valley High School Wilson High School Monroe High School HARNEY Philomath High School Burns High School POLK Central High School CLACKAMAS HOOD RIVER Dallas High School Colton High School Cascade Locks High School Gladstone High School SHERMAN Lake Oswego High School JACKSON Sherman High School Lakeridge High School Butte Falls High School Sandy High School Crater High School UMATILLA North Medford High School Hermiston High School CLATSOP Phoenix High School Pendleton High School Astoria High School Pilot Rock High School Knappa High School JEFFERSON Stanfield High School Seaside High School Madras High School Umatilla High School Warrenton High School LAKE UNION COLUMBIA Lakeview High School LaGrande High School Clatskanie High School Paisley High School North Powder -

Health Career Programs in Oregon's High Schools: 2014

Health Career Programs in Oregon’s High Schools 2014 An inventory of Career and Technical Education and Area Health Education Center health career-related programs CTE and AHEC Health offered in Oregon’s public, charter, and private high schools during the 2013-2014 academic year. Career-Related Programs Complied by the Oregon Healthcare Workforce Institute August 2014 Table of Contents Fast Facts ...................................................................................................................................................... ii Oregon High Schools (Public, Charter, Private), Health-Related Career and Technical Education (CTE), and Area Health Education Center (AHEC) Programs: 2013-2014 ............................................................. 1 Oregon High School Career and Technical Education (CTE) Health-Related Programs: 2013-2014 ........ 16 Oregon Department of Education Approved Health Sciences CTE Programs by High School by Year: 2010 through 2014 ................................................................................................................................... 27 AHEC of Southwest Oregon: 2013-2014 High School Programs .............................................................. 30 Cascades East AHEC: 2013-2014 High School Programs .......................................................................... 37 Northeast Oregon AHEC: 2013-2014 High School Programs.................................................................... 39 Oregon Pacific AHEC: 2013-2014 High School Programs ........................................................................ -

2018 OSAA Band-Orchestra Program

Band/Orchestra May 9-12, 2018 * Oregon State University * Corvallis VALUE THAT GETS BETTER BY THE MILE. OUR PROMISE INCLUDES PEACE OF MIND TIRE PROTECTION FREE LIFETIME TIRE & MILEAGE CARE • If a Tire is Damaged Beyond Repair, • Flat Tire Repairs We’ll Replace its Value. • Tire Rotations & Rebalancing • We Guarantee Our Work for the Life • Tire Pressure Checks of Your Tires. • Brake & Alignment Checks • Free Pre-Trip Safety Checks OSAA / U.S. BANK / LES SCHWAB TIRES STATE CHAMPIONSHIPS Welcome! Welcome to the OSAA / U.S. Bank / Les On behalf of U.S. Bank, welcome to today's Schwab Tires State Championships! Oregon School Activities Association state championship! Teamwork. At the OSAA we believe high school activities Responsibility. provide opportunities for young people to We believe in building strong communities Accomplishment. receive a well‐rounded education that where we live and work. One way we challenges both mind and body. These demonstrate this commitment in Oregon is Whether students are shooting for the hoop, opportunities enrich and expand our by supporting OSAA programs, which marching in time or aiming for the end zone, students’ school experience and help them promote leadership, teamwork and they are practicing skills that will serve them become contributing members of society. sportsmanship in young people. Since 1984, well in school, on the job and in life. U.S. Bank has been proud to support the Participation in activities teaches students OSAA and its 290 member schools, with more At Les Schwab Tire Centers, we are proud of how to be part of something bigger than than four million dollars in contributions to the players and performers of the OSAA.