Building Large Telescopes. II- Reflectors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diffuse Reflecting Power of Various Substances 1

. THE DIFFUSE REFLECTING POWER OF VARIOUS SUBSTANCES 1 By W. W. Coblentz CONTENTS Page I. Introduction . 283 II. Summary of previous investigations 288 III. Apparatus and methods 291 1 The thermopile 292 2. The hemispherical mirror 292 3. The optical system 294 4. Regions of the spectrum examined 297 '. 5. Corrections to observations 298 IV. Reflecting power of lampblack 301 V. Reflecting power of platinum black 305 VI. Reflecting power of green leaves 308 VII. Reflecting power of pigments 311 VIII. Reflecting power of miscellaneous substances 313 IX. Selective reflection and emission of white paints 315 X. Summary 318 Note I. —Variation of the specular reflecting power of silver with angle 319 of incidence I. INTRODUCTION In all radiometric work involving the measurement of radiant energy in absolute value it is necessary to use an instrument that intercepts or absorbs all the incident radiations; or if that is impracticable, it is necessary to know the amount that is not absorbed. The instruments used for intercepting and absorbing radiant energy are usually constructed in the form of conical- shaped cavities which are blackened with lampblack, the expecta- tion being that, after successive reflections within the cavity, the amount of energy lost by passing out through the opening is reduced to a negligible value. 1 This title is used in order to distinguish the reflection of matte surfaces from the (regular) reflection of polished surfaces. The paper gives also data on the specular reflection of polished silver for different angles of incidence, but it seemed unnecessary to include it in the title. -

Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf7b69n8rd Online items available Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Ronald S. Brashear, completed December 12, 1997; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou and updated by Diann Benti in June 2017. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: mssHUB 1-1098 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Edwin Powell Hubble Papers Dates (inclusive): 1900-1989 Collection Number: mssHUB 1-1098 Creator: Hubble, Edwin, 1889-1953. Extent: 1300 pieces, plus ephemera in 34 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Edwin P. Hubble (1889-1953), an astronomer at the Mount Wilson Observatory near Pasadena, California. as well as the diaries and biographical memoirs of his wife, Grace Burke Hubble. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. -

Telescopes and Binoculars

Continuing Education Course Approved by the American Board of Opticianry Telescopes and Binoculars National Academy of Opticianry 8401 Corporate Drive #605 Landover, MD 20785 800-229-4828 phone 301-577-3880 fax www.nao.org Copyright© 2015 by the National Academy of Opticianry. All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 National Academy of Opticianry PREFACE: This continuing education course was prepared under the auspices of the National Academy of Opticianry and is designed to be convenient, cost effective and practical for the Optician. The skills and knowledge required to practice the profession of Opticianry will continue to change in the future as advances in technology are applied to the eye care specialty. Higher rates of obsolescence will result in an increased tempo of change as well as knowledge to meet these changes. The National Academy of Opticianry recognizes the need to provide a Continuing Education Program for all Opticians. This course has been developed as a part of the overall program to enable Opticians to develop and improve their technical knowledge and skills in their chosen profession. The National Academy of Opticianry INSTRUCTIONS: Read and study the material. After you feel that you understand the material thoroughly take the test following the instructions given at the beginning of the test. Upon completion of the test, mail the answer sheet to the National Academy of Opticianry, 8401 Corporate Drive, Suite 605, Landover, Maryland 20785 or fax it to 301-577-3880. Be sure you complete the evaluation form on the answer sheet. -

Researchers Hunting Exoplanets with Superconducting Arrays

Cryocoolers, a Brief Overview .............................. 8 NASA Preps Four Telescope Missions .............. 37 Lake Shore Celebrates 50 Years ....................... 22 ICCRT Recap ..................................................... 38 Recovering Cold Energy and Waste Heat ............ 32 3-D Printing from Aqueous Materials .................. 40 Exoplanet Hunt with ADR-Cooled Superconducting Detector Arrays | 34 Volume 34 Number 3 Researchers Hunting Exoplanets with Superconducting Arrays The key to revealing the exoplanets tucked away around the universe may just be locked up in the advancement of Microwave Kinetic Inductance Detectors (MKIDs), an array of superconducting de- tectors made from platinum sillicide and housed in a cryostat at 100 mK. An astronomy team led by Dr. Benjamin Mazin at the University of California Santa Barbara is using MKID arrays for research on two telescopes, the Hale telescope at Palomar Observatory near San Diego and the Subaru telescope located at the Maunakea Observatory on Hawaii. Mazin began work on MKIDs nearly two decades ago while working under Dr. Jonas Zmuidzinas at Caltech, who co-pioneered the detectors for cosmic microwave background astronomy with Dr. Henry LeDuc at JPL. A look inside the DARKNESS cryostat. Image: Mazin Mazin has since adapted and ad- vanced the technology for the direct im- aging of exoplanets. With direct imaging, telescopes detect light from the planet itself, recording either the self-luminous thermal infrared light that young—and still hot—planets give off, or reflected light from a star that bounces off a planet and then towards the detector. Researchers have previously relied on indirect methods to search for exo- planets, including the radial velocity technique that looks at the spectrum of a star as it’s pushed and pulled by its planetary companions; and transit pho- tometry, where a dip in the brightness of a star is detected as planets cross in front The astronomy team working with Dr. -

The JWST/Nircam Coronagraph: Mask Design and Fabrication

The JWST/NIRCam coronagraph: mask design and fabrication John E. Krista, Kunjithapatham Balasubramaniana, Charles A. Beichmana, Pierre M. Echternacha, Joseph J. Greena, Kurt M. Liewera, Richard E. Mullera, Eugene Serabyna, Stuart B. Shaklana, John T. Traugera, Daniel W. Wilsona, Scott D. Hornerb, Yalan Maob, Stephen F. Somersteinb, Gopal Vasudevanb, Douglas M. Kellyc, Marcia J. Riekec aJet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasasdena, CA, USA 91109; bLockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Palo Alto, CA, USA 94303; cUniversity of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA 85721 ABSTRACT The NIRCam instrument on the James Webb Space Telescope will provide coronagraphic imaging from λ=1-5 µm of high contrast sources such as extrasolar planets and circumstellar disks. A Lyot coronagraph with a variety of circular and wedge-shaped occulting masks and matching Lyot pupil stops will be implemented. The occulters approximate grayscale transmission profiles using halftone binary patterns comprising wavelength-sized metal dots on anti-reflection coated sapphire substrates. The mask patterns are being created in the Micro Devices Laboratory at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory using electron beam lithography. Samples of these occulters have been successfully evaluated in a coronagraphic testbed. In a separate process, the complex apertures that form the Lyot stops will be deposited onto optical wedges. The NIRCam coronagraph flight components are expected to be completed this year. Keywords: NIRCam, JWST, James Webb Space Telescope, coronagraph 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The planet/star contrast problem Observations of extrasolar planet formation (e.g. protoplanetary disks) and planetary systems are hampered by the large contrast differences between these targets and their much brighter stars. -

A Newly-Discovered Accurate Early Drawing of M51, the Whirlpool Nebula

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage , 11(2), 107-115 (2008). A NEWLY-DISCOVERED ACCURATE EARLY DRAWING OF M51, THE WHIRLPOOL NEBULA William Tobin 6 rue Saint Louis, 56000 Vannes, France. E-mail: [email protected] and J.B. Holberg Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, 1541 East University Boulevard, Tucson, AZ 85721, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We have discovered a lost drawing of M51, the nebula in which spiral structure was first discovered by Lord Rosse. The drawing was made in April 1862 by Jean Chacornac at the Paris Observatory using Léon Foucault’s newly-completed 80-cm silvered-glass reflecting telescope. Comparison with modern images shows that Chacornac’s drawing was more accurate with respect to gross structure and showed fainter details than any other nineteenth century drawing, although its superiority would not have been apparent at the time without nebular photography to provide a standard against which to judge drawing quality. M51 is now known as the Whirlpool Nebula, but the astronomical appropriation of ‘whirlpool’ predates Rosse’s discovery. Keywords: reflecting telescopes, nebulae, spiral structure, Léon Foucault, Lord Rosse, M51, Whirlpool Nebula 1 REFLECTING TELESCOPES AND SPIRAL STRUCTURE The French physicist Léon Foucault (1819–1868) is the father of the reflecting telescope in its modern form, with large, optically-perfect, metallized glass or ceramic mirrors. Foucault achieved this breakthrough while working as ‘physicist’ at the Paris Observatory in the late 1850s. The largest telescope that he built (Foucault, 1862) had a silvered-glass, f/5.6 primary mirror of 80-cm diameter in a Newtonian configura- tion (see Figure 1). -

Large Telescopes and Why We Need Them Transcript

Large telescopes and why we need them Transcript Date: Wednesday, 9 May 2012 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 9 May 2012 Large Telescopes And Why we Need Them Professor Carolin Crawford Astronomy is a comparatively passive science, in that we can’t engage in laboratory experiments to investigate how the Universe works. To study any cosmic object outside of our Solar System, we can only work with the light it emits that happens to fall on Earth. How much we can interpret and understand about the Universe around us depends on how well we can collect and analyse that light. This talk is about the first part of that problem: how we improve the collection of light. The key problem for astronomers is that all stars, nebulae and galaxies are so very far away that they appear both very small, and very faint - some so much so that they can’t be seen without the help of a telescope. Its role is simply to collect more light than the unaided eye can, making astronomical sources appear both bigger and brighter, or even just to make most of them visible in the first place. A new generation of electronic detectors have made observations with the eye redundant. We now have cameras to record the images directly, or once it has been split into its constituent wavelengths by spectrographs. Even though there are a whole host of ingenious and complex instruments that enable us to record and analyse the light, they are still only able to work with the light they receive in the first place. -

Demonstration of Vortex Coronagraph Concepts for On-Axis Telescopes on the Palomar Stellar Double Coronagraph

Demonstration of vortex coronagraph concepts for on-axis telescopes on the Palomar Stellar Double Coronagraph Dimitri Maweta, Chris Sheltonb, James Wallaceb, Michael Bottomc, Jonas Kuhnb, Bertrand Mennessonb, Rick Burrussb, Randy Bartosb, Laurent Pueyod, Alexis Carlottie, and Eugene Serabynb aEuropean Southern Observatory, Alonso de C´ordova 3107, Vitacura, Casilla 19001, Chile; bJet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA; cCalifornia Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91106, USA; dSpace Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA; eInstitut de Plan´etologieet d'Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG), University Joseph Fourier, CNRS, BP 53, 38041, Grenoble, France; ABSTRACT Here we present preliminary results of the integration of two recently proposed vortex coronagraph (VC) concepts for on-axis telescopes on the Stellar Double Coronagraph (SDC) bench behind PALM-3000, the extreme adaptive optics system of the 200-inch Hale telescope of Palomar observatory. The multi-stage vortex coronagraph (MSVC) uses the ability of the vortex to move light in and out of apertures through multiple VC in series to restore the nominal attenuation capability of the charge 2 vortex regardless of the aperture obscurations. The ring-apodized vortex coronagraph (RAVC) is a one-stage apodizer exploiting the VC Lyot-plane amplitude distribution in order to perfectly null the diffraction from any central obscuration size, and for any vortex topological charge. The RAVC is thus a simple concept that makes the VC immune to diffraction effects of the secondary mirror. It combines a vortex phase mask in the image plane with a single pupil-based amplitude ring apodizer, tailor-made to exploit the unique convolution properties of the VC at the Lyot-stop plane. -

Aplea for Reflectors

A PLEA FOR REFLECTORS Pedro RÉ http://pedroreastrophotography.com/ In 1867 John Browing (c1833-1925)1 published a trade catalogue entitled “A Plea for Reflectors: Being a Description of the New Astronomical Telescopes with Silvered-Glass Specula; And Instructions for adjusting and Using Them”. This catalogue had six editions that were published until 18762. Browning describes his range of reflecting telescopes, how to use them and compares these with achromatic refractors of comparable apertures. It also contains numerous details of its extensive range of glass silvered specula, eyepieces, micrometres, barometers and microscopes (Figure 1). The back of the booklet contains testimonials from satisfied customers, many of them distinguished amateurs and professionals. By publishing “A Plea for Reflectors”, J. Browning & Co. became one of the first to mass produce telescopes for the amateur (Figure 2). The popularity of the Newtonian reflector as the instrument of choice for the amateur astronomer followed the pioneering work of George Henry With (1827-1904). With began making silvered-glass mirrors in the early 1860's following his retirement as schoolmaster at the Blue Coat School, Hereford. With did not actually make telescopes. His principal customer was John Browning, the London instrument maker well-known for his spectroscopes and telescopes. Browning's business flourished to circa 1905, possibly first starting at 1 Norfolk Street, Strand circa 1866. The firm had their 'factory' in Vine Street EC3 (1872-76) and Southampton Street north off the Strand (1877-82) and William Street (1887). The shop was at 111 Minories (near Tower Hill) working under the name Spencer, Browning and Co. -

The Herschels and Their Astronomy

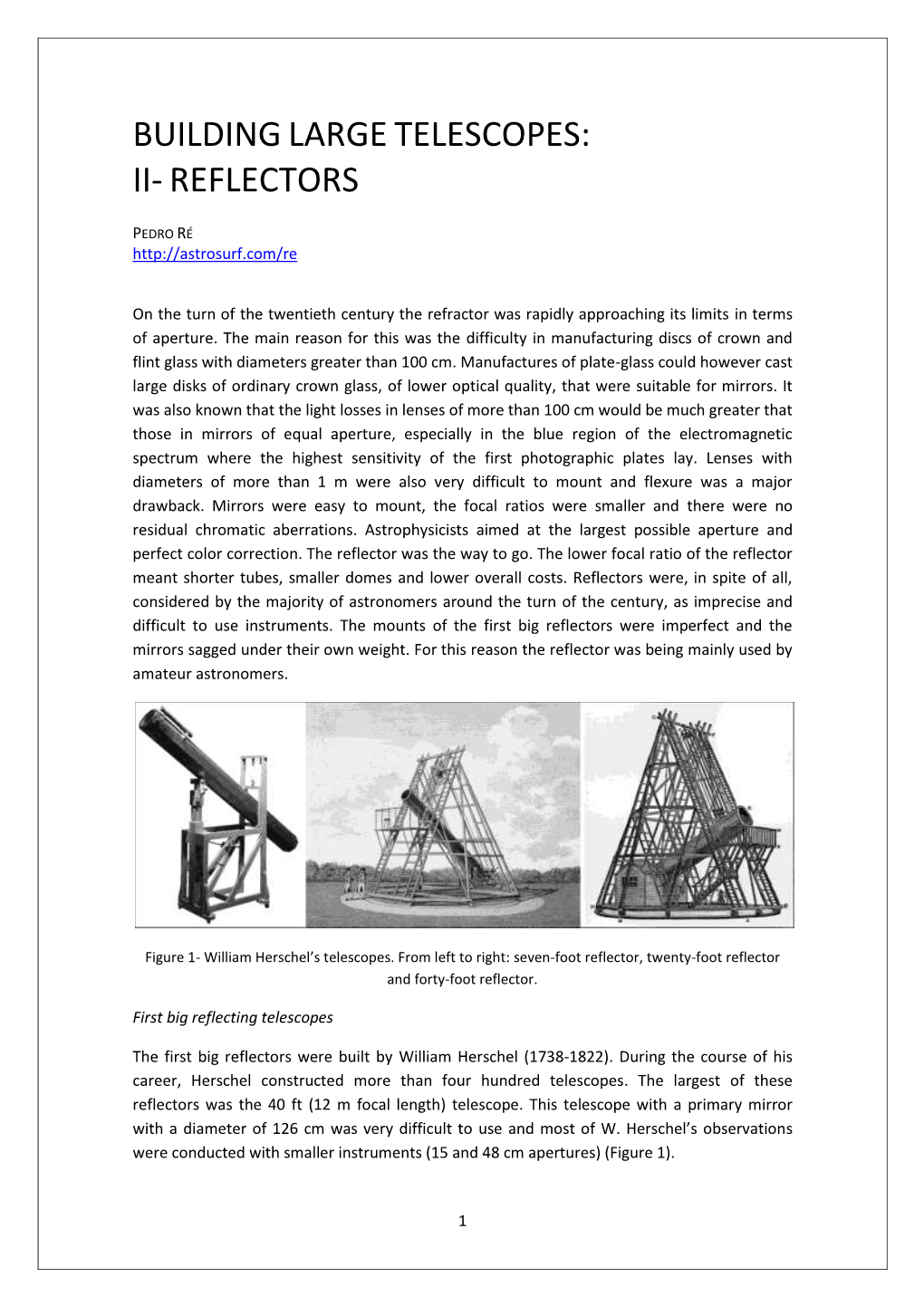

The Herschels and their Astronomy Mary Kay Hemenway 24 March 2005 outline • William Herschel • Herschel telescopes • Caroline Herschel • Considerations of the Milky Way • William Herschel’s discoveries • John Herschel Wm. Herschel (1738-1822) • Born Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel in Hanover, Germany • A bandboy with the Hanoverian Guards, later served in the military; his father helped him to leave Germany for England in 1757 • Musician in Bath • He read Smith's Harmonies, and followed by reading Smith's Optics - it changed his life. Miniature portrait from 1764 Discovery of Uranus 1781 • William Herschel used a seven-foot Newtonian telescope • "in the quartile near zeta Tauri the lowest of the two is a curious either Nebulous Star or perhaps a Comet” • He called it “Georgium Sidus" after his new patron, George Ill. • Pension of 200 pounds a year and knighted, the "King's Astronomer” -- now astronomy full time. Sir William Herschel • Those who had received a classical education in astronomy agreed that their job was to study the sun, moon, planets, comets, individual stars. • Herschel acted like a naturalist, collecting specimens in great numbers, counting and classifying them, and later trying to organize some into life cycles. • Before his discovery of Uranus, Fellows of the Royal Society had contempt for his ignorance of basic procedures and conventions. Isaac Newton's reflecting telescope 1671 William Herschel's 20-foot, 1783 Account of some Observations tending to investigate the Construction of the Heavens Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (1784) vol. 74, pp. 437-451 In a former paper I mentioned, that a more powerful instrument was preparing for continuing my reviews of the heavens. -

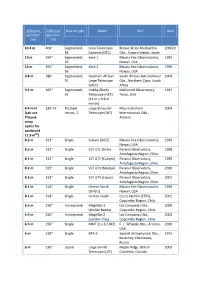

Effective Aperture 3.6–4.9 M) 4.7 M 186″ Segmented, MMT (6×1.8 M) F

Effective Effective Mirror type Name Site Built aperture aperture (m) (in) 10.4 m 409″ Segmented, Gran Telescopio Roque de los Muchachos 2006/9 36 Canarias (GTC) Obs., Canary Islands, Spain 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 1 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1993 36 Hawaii, USA 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 2 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1996 36 Hawaii, USA 9.8 m 386″ Segmented, Southern African South African Astronomical 2005 91 Large Telescope Obs., Northern Cape, South (SALT) Africa 9.2 m 362″ Segmented, Hobby-Eberly McDonald Observatory, 1997 91 Telescope (HET) Texas, USA (11 m × 9.8 m mirror) 8.4 m×2 330″×2 Multiple Large Binocular Mount Graham 2004 (can use mirror, 2 Telescope (LBT) Internationals Obs., Phased- Arizona array optics for combined 11.9 m[2]) 8.2 m 323″ Single Subaru (JNLT) Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 Hawaii, USA 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT1 (Antu) Paranal Observatory, 1998 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT2 (Kueyen) Paranal Observatory, 1999 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT3 (Melipal) Paranal Observatory, 2000 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT4 (Yepun) Paranal Observatory, 2001 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini North Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 (Gillett) Hawaii, USA 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini South Cerro Pachón (CTIO), 2001 Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 1 Las Campanas Obs., 2000 (Walter Baade) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 2 Las Campanas Obs., 2002 (Landon Clay) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Single MMT (1 x 6.5 M1) F. -

Chapter 25 the Reflection of Light: Mirrors

Chapter 25 The Reflection of Light: Mirrors 25.1 Wave Fronts and Rays Defining wave fronts and rays. Consider a sound wave since it is easier to visualize. Shown is a hemispherical view of a sound wave emitted by a pulsating sphere. The rays are perpendicular to the wave fronts (e.g. crests) which are separated from each other by the wavelength of the wave, λ. 25.1 Wave Fronts and Rays The positions of two spherical wave fronts are shown in (a) with their diverging rays. At large distances from the source, the wave fronts become less and less curved and approach the limiting case of a plane wave shown in (b). A plane wave has flat wave fronts and rays parallel to each other. We will consider light waves as plane waves and will represent them by their rays. 25.2 The Reflection of Light LAW OF REFLECTION FROM FLAT MIRRORS. The incident ray, the reflected ray, and the normal to the surface all lie in the same plane, and the angle of incidence, θi, equals the angle of reflection, θr. θi = θr 25.2 The Reflection of Light In specular reflection, the reflected rays are parallel to each other. In diffuse reflection, light is reflected in random directions. Flat, reflective surfaces, Rough surfaces, e.g. mirrors, polished metal, e.g. paper, wood, unpolished surface of a calm pond of water metal, surface of a pond on a windy day 25.3 The Formation of Images by a Plane Mirror Your image in a flat mirror has four properties: 1.