LIST of ABBREVIATIONS ABP ADCC BPI C3 CAMP Cfu CGD CM I CR1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Macrophages Deal with Death

REVIEWS CELL DEATH AND IMMUNITY How macrophages deal with death Greg Lemke Abstract | Tissue macrophages rapidly recognize and engulf apoptotic cells. These events require the display of so- called eat-me signals on the apoptotic cell surface, the most fundamental of which is phosphatidylserine (PtdSer). Externalization of this phospholipid is catalysed by scramblase enzymes, several of which are activated by caspase cleavage. PtdSer is detected both by macrophage receptors that bind to this phospholipid directly and by receptors that bind to a soluble bridging protein that is independently bound to PtdSer. Prominent among the latter receptors are the MER and AXL receptor tyrosine kinases. Eat-me signals also trigger macrophages to engulf virus- infected or metabolically traumatized, but still living, cells, and this ‘murder by phagocytosis’ may be a common phenomenon. Finally , the localized presentation of PtdSer and other eat- me signals on delimited cell surface domains may enable the phagocytic pruning of these ‘locally dead’ domains by macrophages, most notably by microglia of the central nervous system. In long- lived organisms, abundant cell types are often process. Efferocytosis is a remarkably efficient business: short- lived. In the human body, for example, the macrophages can engulf apoptotic cells in less than lifespan of many white blood cells — including neutro- 10 minutes, and it is therefore difficult experimentally to phils, eosinophils and platelets — is less than 2 weeks. detect free apoptotic cells in vivo, even in tissues where For normal healthy humans, a direct consequence of large numbers are generated7. Many of the molecules this turnover is the routine generation of more than that macrophages and other phagocytes use to recognize 100 billion dead cells each and every day of life1,2. -

Complement Component 4 Genes Contribute Sex-Specific Vulnerability in Diverse Illnesses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/761718; this version posted September 9, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Complement component 4 genes contribute sex-specific vulnerability in diverse illnesses Nolan Kamitaki1,2, Aswin Sekar1,2, Robert E. Handsaker1,2, Heather de Rivera1,2, Katherine Tooley1,2, David L. Morris3, Kimberly E. Taylor4, Christopher W. Whelan1,2, Philip Tombleson3, Loes M. Olde Loohuis5,6, Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium7, Michael Boehnke8, Robert P. Kimberly9, Kenneth M. Kaufman10, John B. Harley10, Carl D. Langefeld11, Christine E. Seidman1,12,13, Michele T. Pato14, Carlos N. Pato14, Roel A. Ophoff5,6, Robert R. Graham15, Lindsey A. Criswell4, Timothy J. Vyse3, Steven A. McCarroll1,2 1 Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA 2 Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, USA 3 Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, King’s College London, London WC2R 2LS, UK 4 Rosalind Russell / Ephraim P Engleman Rheumatology Research Center, Division of Rheumatology, UCSF School of Medicine, San Francisco, California 94143, USA 5 Department of Human Genetics, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA 6 Center for Neurobehavioral Genetics, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA 7 A full list of collaborators is in Supplementary Information. -

Investigation of Candidate Genes and Mechanisms Underlying Obesity

Prashanth et al. BMC Endocrine Disorders (2021) 21:80 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-021-00718-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Investigation of candidate genes and mechanisms underlying obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus using bioinformatics analysis and screening of small drug molecules G. Prashanth1 , Basavaraj Vastrad2 , Anandkumar Tengli3 , Chanabasayya Vastrad4* and Iranna Kotturshetti5 Abstract Background: Obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder ; however, the etiology of obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus remains largely unknown. There is an urgent need to further broaden the understanding of the molecular mechanism associated in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Methods: To screen the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that might play essential roles in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus, the publicly available expression profiling by high throughput sequencing data (GSE143319) was downloaded and screened for DEGs. Then, Gene Ontology (GO) and REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis were performed. The protein - protein interaction network, miRNA - target genes regulatory network and TF-target gene regulatory network were constructed and analyzed for identification of hub and target genes. The hub genes were validated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and RT- PCR analysis. Finally, a molecular docking study was performed on over expressed proteins to predict the target small drug molecules. Results: A total of 820 DEGs were identified between -

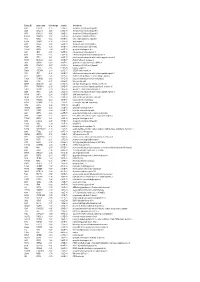

Appendix Table A.2.3.1 Full Table of All Chicken Proteins and Human Orthologs Pool Accession Human Human Protein Human Product Cell Angios Log2( Endo Gene Comp

Appendix table A.2.3.1 Full table of all chicken proteins and human orthologs Pool Accession Human Human Protein Human Product Cell AngioS log2( Endo Gene comp. core FC) Specific CIKL F1NWM6 KDR NP_002244 kinase insert domain receptor (a type III receptor tyrosine M 94 4 kinase) CWT Q8AYD0 CDH5 NP_001786 cadherin 5, type 2 (vascular endothelium) M 90 8.45 specific CWT Q8AYD0 CDH5 NP_001786 cadherin 5, type 2 (vascular endothelium) M 90 8.45 specific CIKL F1P1Y9 CDH5 NP_001786 cadherin 5, type 2 (vascular endothelium) M 90 8.45 specific CIKL F1P1Y9 CDH5 NP_001786 cadherin 5, type 2 (vascular endothelium) M 90 8.45 specific CIKL F1N871 FLT4 NP_891555 fms-related tyrosine kinase 4 M 86 -1.71 CWT O73739 EDNRA NP_001948 endothelin receptor type A M 81 -8 CIKL O73739 EDNRA NP_001948 endothelin receptor type A M 81 -8 CWT Q4ADW2 PROCR NP_006395 protein C receptor, endothelial M 80 -0.36 CIKL Q4ADW2 PROCR NP_006395 protein C receptor, endothelial M 80 -0.36 CIKL F1NFQ9 TEK NP_000450 TEK tyrosine kinase, endothelial M 77 7.3 specific CWT Q9DGN6 ECE1 NP_001106819 endothelin converting enzyme 1 M 74 -0.31 CIKL Q9DGN6 ECE1 NP_001106819 endothelin converting enzyme 1 M 74 -0.31 CWT F1NIF0 CA9 NP_001207 carbonic anhydrase IX I 74 CIKL F1NIF0 CA9 NP_001207 carbonic anhydrase IX I 74 CWT E1BZU7 AOC3 NP_003725 amine oxidase, copper containing 3 (vascular adhesion protein M 70 1) CIKL E1BZU7 AOC3 NP_003725 amine oxidase, copper containing 3 (vascular adhesion protein M 70 1) CWT O93419 COL18A1 NP_569712 collagen, type XVIII, alpha 1 E 70 -2.13 CIKL O93419 -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Common Differentially Expressed Genes and Pathways Correlating Both Coronary Artery Disease and Atrial Fibrillation

EXCLI Journal 2021;20:126-141– ISSN 1611-2156 Received: December 08, 2020, accepted: January 11, 2021, published: January 18, 2021 Supplementary material to: Original article: COMMON DIFFERENTIALLY EXPRESSED GENES AND PATHWAYS CORRELATING BOTH CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE AND ATRIAL FIBRILLATION Youjing Zheng, Jia-Qiang He* Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA * Corresponding author: Jia-Qiang He, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology, Virginia Tech, Phase II, Room 252B, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA. Tel: 1-540-231-2032. E-mail: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4825-7046 Youjing Zheng https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0640-5960 Jia-Qiang He http://dx.doi.org/10.17179/excli2020-3262 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Supplemental Table 1: Abbreviations used in the paper Abbreviation Full name ABCA5 ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 5 ABCB6 ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 6 (Langereis blood group) ABCB9 ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 9 ABCC10 ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 10 ABCC13 ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 13 (pseudogene) ABCC5 ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 5 ABCD3 ATP binding cassette subfamily D member 3 ABCE1 ATP binding cassette subfamily E member 1 ABCG1 ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 1 ABCG4 ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 4 ABHD18 Abhydrolase domain -

Entrez ID Gene Name Fold Change Q-Value Description

Entrez ID gene name fold change q-value description 4283 CXCL9 -7.25 5.28E-05 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 3627 CXCL10 -6.88 6.58E-05 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 6373 CXCL11 -5.65 3.69E-04 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 405753 DUOXA2 -3.97 3.05E-06 dual oxidase maturation factor 2 4843 NOS2 -3.62 5.43E-03 nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible 50506 DUOX2 -3.24 5.01E-06 dual oxidase 2 6355 CCL8 -3.07 3.67E-03 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 10964 IFI44L -3.06 4.43E-04 interferon-induced protein 44-like 115362 GBP5 -2.94 6.83E-04 guanylate binding protein 5 3620 IDO1 -2.91 5.65E-06 indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 8519 IFITM1 -2.67 5.65E-06 interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 3433 IFIT2 -2.61 2.28E-03 interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 54898 ELOVL2 -2.61 4.38E-07 ELOVL fatty acid elongase 2 2892 GRIA3 -2.60 3.06E-05 glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 3 6376 CX3CL1 -2.57 4.43E-04 chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1 7098 TLR3 -2.55 5.76E-06 toll-like receptor 3 79689 STEAP4 -2.50 8.35E-05 STEAP family member 4 3434 IFIT1 -2.48 2.64E-03 interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 4321 MMP12 -2.45 2.30E-04 matrix metallopeptidase 12 (macrophage elastase) 10826 FAXDC2 -2.42 5.01E-06 fatty acid hydroxylase domain containing 2 8626 TP63 -2.41 2.02E-05 tumor protein p63 64577 ALDH8A1 -2.41 6.05E-06 aldehyde dehydrogenase 8 family, member A1 8740 TNFSF14 -2.40 6.35E-05 tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 14 10417 SPON2 -2.39 2.46E-06 spondin 2, extracellular matrix protein 3437 -

The Role of the Complement System in Cancer

REVIEW The Journal of Clinical Investigation The role of the complement system in cancer Vahid Afshar-Kharghan Section of Benign Hematology, University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA. In addition to being a component of innate immunity and an ancient defense mechanism against invading pathogens, complement activation also participates in the adaptive immune response, inflammation, hemostasis, embryogenesis, and organ repair and development. Activation of the complement system via classical, lectin, or alternative pathways generates anaphylatoxins (C3a and C5a) and membrane attack complex (C5b-9) and opsonizes targeted cells. Complement activation end products and their receptors mediate cell-cell interactions that regulate several biological functions in the extravascular tissue. Signaling of anaphylatoxin receptors or assembly of membrane attack complex promotes cell dedifferentiation, proliferation, and migration in addition to reducing apoptosis. As a result, complement activation in the tumor microenvironment enhances tumor growth and increases metastasis. In this Review, I discuss immune and nonimmune functions of complement proteins and the tumor-promoting effect of complement activation. tion pathways is the formation of the C3 convertase complex on Introduction the surface of targeted cells, summarized in Figure 1, A–C. After The complement system is a cascade of serine proteases encod- forming C3 convertase, complement is able to carry out its effec- ed by genes originating from the same ancestral genes as coag- tor functions. ulation proteins (1). Like the coagulation system, complement In all three complement activation pathways, C3 conver- activation involves several steps, is tightly regulated, and requires tase complex cleaves C3 molecules to C3a, one of the two major both plasma and membrane proteins (2, 3). -

Mouse Samples

AssayGate, Inc. 9607 Dr. Perry Road Suite 103. Ijamsville, MD 21754. Tel: (301)874-0988. Fax: (301)560-8288. ELISA Services for Mouse Samples ID Mouse Analyte 1 1, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 (DHVD3) 2 17-Hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) 3 2',5'-Oligoadenylate Synthetase 1 (OAS1) 4 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 (HVD3) 5 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) 6 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) 7 A Disintegrin And Metalloprotease 8 (ADAM8) 8 A Disintegrin And Metalloprotease 9 (ADAM9) 9 Acetyl Coenzyme A Carboxylase Alpha (ACACa) 10 Acetylcholine (ACH) 11 Acid Phosphatase 1 (ACP1) 12 Acid Phosphatase 2, Lysosomal (ACP2) 13 Acid Phosphatase 3, Prostatic (ACP3) 14 Acid Phosphatase 5, Tartrate Resistant (ACP5) 15 Actin Alpha 2, Smooth Muscle (ACTa2) 16 Actin Related Protein 2/3 Complex Subunit 4 (ARPC4) 17 Actinin Alpha 2 (ACTN2) 18 Activated Leukocyte Cell Adhesion Molecule (ALCAM) 19 Activated Protein C (APC) 20 Activating Transcription Factor 5 (ATF5) 21 Activin A (ACVA) 22 Activin AB (ACVAB) 23 Activity Regulated Cytoskeleton Associated Protein (ARC) 24 Adenylate Cyclase Activating Polypeptide 1, Pituitary (ADCYAP1) 25 Adiponectin (ADP) 26 Adiponectin Receptor 1 (ADIPOR1) 27 Adrenergic Receptor, Alpha 1A (ADRa1A) 28 Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) 29 Adrenomedullin (ADM) 30 Advanced Glycosylation End Product Specific Receptor (AGER) 31 Afamin (AFM) 32 Aggrecan (AGC) 33 Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) 1 34 Albumin (ALB) 35 Alcohol Dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1) 36 Alcohol Dehydrogenase 7 (ADH7) 37 Aldehyde Dehydrogenase, Mitochondrial (ALDM) 38 Aldosterone (ALD) 39 Alkaline -

Complement As a Therapeutic Target in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases

cells Review Complement as a Therapeutic Target in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases María Galindo-Izquierdo * and José Luis Pablos Alvarez Servicio de Reumatología, Instituto de Investigación 12 de Octubre, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The complement system (CS) includes more than 50 proteins and its main function is to recognize and protect against foreign or damaged molecular components. Other homeostatic functions of CS are the elimination of apoptotic debris, neurological development, and the control of adaptive immune responses. Pathological activation plays prominent roles in the pathogenesis of most autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, and ANCA-associated vasculitis. In this review, we will review the main rheumatologic autoimmune processes in which complement plays a pathogenic role and its potential relevance as a therapeutic target. Keywords: complement system; pathogenesis; therapeutic blockade; rheumatic autoimmune diseases 1. Introduction The complement system (CS) includes more than 50 proteins that can be found as soluble forms, anchored to the cell membranes, or intracellularly [1]. Most of the com- plement proteins are synthesized in the liver, although other cell types, especially mono- cytes/macrophages, can produce them. Tissue distribution is variable and a higher con- Citation: Galindo-Izquierdo, M.; centration of these proteins is found in certain locations such as the kidney or brain. The Pablos Alvarez, J.L. Complement as a main function of the CS is to recognize and protect against foreign or damaged molecular Therapeutic Target in Systemic components, directly as microorganisms, and indirectly as immune complexes (IC). -

(MDR/TAP), Member 1 ABL1 NM 00

Official Symbol Accession Official Full Name ABCB1 NM_000927.3 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member 1 ABL1 NM_005157.3 c-abl oncogene 1, non-receptor tyrosine kinase ADA NM_000022.2 adenosine deaminase AHR NM_001621.3 aryl hydrocarbon receptor AICDA NM_020661.1 activation-induced cytidine deaminase AIRE NM_000383.2 autoimmune regulator APP NM_000484.3 amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein ARG1 NM_000045.2 arginase, liver ARG2 NM_001172.3 arginase, type II ARHGDIB NM_001175.4 Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI) beta ATG10 NM_001131028.1 ATG10 autophagy related 10 homolog (S. cerevisiae) ATG12 NM_004707.2 ATG12 autophagy related 12 homolog (S. cerevisiae) ATG16L1 NM_198890.2 ATG16 autophagy related 16-like 1 (S. cerevisiae) ATG5 NM_004849.2 ATG5 autophagy related 5 homolog (S. cerevisiae) ATG7 NM_001136031.2 ATG7 autophagy related 7 homolog (S. cerevisiae) ATM NM_000051.3 ataxia telangiectasia mutated B2M NM_004048.2 beta-2-microglobulin B3GAT1 NM_018644.3 beta-1,3-glucuronyltransferase 1 (glucuronosyltransferase P) BATF NM_006399.3 basic leucine zipper transcription factor, ATF-like BATF3 NM_018664.2 basic leucine zipper transcription factor, ATF-like 3 BAX NM_138761.3 BCL2-associated X protein BCAP31 NM_005745.7 B-cell receptor-associated protein 31 BCL10 NM_003921.2 B-cell CLL/lymphoma 10 BCL2 NM_000657.2 B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 BCL2L11 NM_138621.4 BCL2-like 11 (apoptosis facilitator) BCL3 NM_005178.2 B-cell CLL/lymphoma 3 BCL6 NM_001706.2 B-cell CLL/lymphoma 6 BID NM_001196.2 BH3 interacting domain death agonist BLNK NM_013314.2 -

Supplement, Table 8. Genes Affected by Celecoxib in "Immune Response" Gene Ontology Category

Supplement, Table 8. Genes affected by Celecoxib in "immune response" Gene Ontology category Geometri UniGene HUGO Parametric Gene c mean of Cluster ID Symbol p-value ratios P/F Hs.25647 FOS v-fos FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog 0.621 0.0407 Hs.423 PAP pancreatitis-associated protein 0.683 0.0040 Hs.407546 TNFAIP6 tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 6 0.736 0.0053 Hs.308680 C1R complement component 1, r subcomponent 0.751 0.0179 Hs.789 CXCL1 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (melanoma growth stimulating activity, alpha) 0.762 0.0579 Hs.110675 APOE apolipoprotein E 0.762 0.0253 Hs.407506 INHA inhibin, alpha 0.764 0.0185 Hs.78065 C7 complement component 7 0.765 0.0081 Hs.134231 VPS45A vacuolar protein sorting 45A (yeast) 0.78 0.0000 Hs.436042 CXCL12 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (stromal cell-derived factor 1) 0.788 0.0189 Hs.172674 NFATC3 nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin-dependent 3 0.793 0.0019 Hs.421342 STAT3 signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (acute-phase response factor) 0.799 0.0314 Hs.1735 INHBB inhibin, beta B (activin AB beta polypeptide) 0.801 0.0311 Hs.458355 C1S complement component 1, s subcomponent 0.815 0.0238 Hs.77546 ANKRD15 ankyrin repeat domain 15 0.818 0.0017 GALNAC4S- Hs.523379 6ST B cell RAG associated protein 0.829 0.0522 Hs.421194 TPST1 tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase 1 0.831 0.0206 Hs.7957 ADAR adenosine deaminase, RNA-specific 0.834 0.0210 Hs.374357 NFRKB nuclear factor related to kappa B binding protein 0.849 0.0104 Hs.1281 C5 complement component