The Island of California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Maritime Russia and the North Pacific Arc Dianne Meredith Russia Has Always Held an Ambiguous Position in World Geography

Early Maritime Russia and the North Pacific Arc Dianne Meredith Russia has always held an ambiguous position in world geography. Like most other great powers, Russia spread out from a small, original core area of identity. The Russian-Kievan core was located west of the Ural Mountains. Russia’s earlier history (1240-1480) was deeply colored by a Mongol-Tatar invasion in the thirteenth century. By the time Russia cast off Mongol rule, its worldview had developed to reflect two and one-half centuries of Asiatic rather than European dominance, hence the old cliché, scratch a Russian and you find a Tatar. This was the beginning of Russia’s long search of identity as neither European nor Asian, but Eurasian. Russia has a longer Pacific coastline than any other Asian country, yet a Pacific identity has been difficult to assume, in spite of over four hundred years of exploration (Map 1). Map 1. Geographic atlas of the Russian Empire (1745), digital copy by the Russian State Library. Early Pacific Connections Ancient peoples from what is now present-day Russia had circum-Pacific connections via the North Pacific arc between North America and Asia. Today this arc is separated by a mere fifty-six miles at the Bering Strait, but centuries earlier it was part of a broad subcontinent more than one-thousand miles long. Beringia, as it is now termed, was not fully glaciated during the Pleistocene Ice Age; in fact, there was not any area of land within one hundred miles of the Bering Strait itself that was completely glaciated within the last million years, while for much of that time a broad band of ice to the east covered much of present-day Alaska. -

Ohlone-Portola Heritage Trail Statement of Significance

State of California Natural Resources Agency Primary# DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # Trinomial CONTINUATION SHEET Property Name: __California Historical Landmarks Associated with the Ohlone-Portolá Heritage Trail______ Page __1___ of __36__ B10. Statement of Significance (continued): The following Statement of Significance establishes the common historic context for California Historical Landmarks associated with the October-November 1769 expedition of Gaspar de Portolá through what is now San Mateo County, as part of a larger expedition through the southern San Francisco Bay region, encountering different Ohlone communities, known as the Ohlone-Portolá Heritage Trail. This context establishes the significance of these landmark sites as California Historical Landmarks for their association with an individual having a profound influence on the history of California, Gaspar de Portolá, and a group having a profound influence on the history of California, the Ohlone people, both associated with the Portolá Expedition Camp at Expedition. This context amends seven California Historical Landmarks, and creates two new California Historical Landmark nominations. The Statement of Significance applies to the following California Historical Landmarks, updating their names and historic contexts. Each meets the requirements of California PRC 5024.1(2) regarding review of state historical landmarks preceding #770, and the criteria necessary for listing as California Historical Landmarks. Because these landmarks indicate sites with no extant -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Paskaerte van Nova Granada, en t'Eylandt California . 1666 Stock#: 40838dr2 Map Maker: Goos Date: 1666 Place: Amsterdam Color: Hand Colored Condition: VG Size: 21 x 17 inches Price: SOLD Description: Goos’ Iconic Sea Chart Showing California as an Island Fine example of Pieter Goos' highly coveted map of California as an island, with its contiguous regions. This highly-detailed map is one of the best illustrations of the island of California and one of only a couple of large format maps to focus on the feature. It is also one of the first sea charts of the island. For these reasons, Goos' map is one of the most sought after of all maps of California as an island. Tooley referred to the map as, "Perhaps the most attractive and certainly the most definite representation of California as an island. California is the centre and 'raison d'etre' of the map" (map 22, plate 37). Burden agrees, calling it “one of the most desirable of all California as an island maps” (map 391). It is featured on the cover of McLaughlin and Mayo's authoritative The Mapping of California as an Island checklist and is probably the most recognizable map of the genre. The chart is half filled with the Pacific Ocean, which is criss-crossed with rhumb lines and dotted with a compass rose and two ships in full sail. In the lower left is the scale which is framed by two putti holding dividers and a cross staff. -

See PDF History

History According to California Indian traditional beliefs, their ancestors were created here and have lived here forever. Most anthropologists believe California Indians descended from people who crossed from Asia into North America over a land bridge that joined the two continents late in the Pleistocene Epoch. It is thought that Native Americans lived here for 15 millenia before the first European explorer sailed California's coast in the 1500s. European explorers came to California initially in a search for what British explorers called the Northwest Passage and what the Spaniards called the Strait of Anián. In any event, it was an attempt to find a shortcut between Asia's riches -- silk, spices, jewels -- and Europe that drove the discovery voyages. The now famous voyage of Columbus in 1492 was an attempt to find this mythical shortcut. Forty-seven years after Columbus's voyage, Francisco de Ulloa led an expedition from Acapulco that sought a non-existent passage from the Gulf of California through to the Pacific Ocean. California was thought to be an island, in large part probably due to a Spanish novel called Las Sergas de Esplandián (The Exploits of Esplandián) written by Garcí Rodríguez Ordóñez de Montalvo. The "island" of California is depicted in this map. Montalvo's mythical island of California was populated by a tribe of J. Speed. "The Island of California: California as black women who lived like Amazons. Early explorers apparently an Island Map," from America (Map of America named the Baja California peninsula after the mythical island, and in made in London in 1626 or 1676). -

California History Online | the Physical Setting

Chapter 1: The Physical Setting Regions and Landforms: Let's take a trip The land surface of California covers almost 100 million acres. It's the third largest of the states; only Alaska and Texas are larger. Within this vast area are a greater range of landforms, a greater variety of habitats, and more species of plants and animals than in any area of comparable size in all of North America. California Coast The coastline of California stretches for 1,264 miles from the Oregon border in the north to Mexico in the south. Some of the most breathtaking scenery in all of California lies along the Pacific coast. More than half of California's people reside in the coastal region. Most live in major cities that grew up around harbors at San Francisco Bay, San Diego Bay and the Los Angeles Basin. San Francisco Bay San Francisco Bay, one of the finest natural harbors in the world, covers some 450 square miles. It is two hundred feet deep at some points, but about two-thirds is less than twelve feet deep. The bay region, the only real break in the coastal mountains, is the ancestral homeland of the Ohlone and Coast Miwok Indians. It became the gateway for newcomers heading to the state's interior in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Tourism today is San Francisco's leading industry. San Diego Bay A variety of Yuman-speaking people have lived for thousands of years around the shores of San Diego Bay. European settlement began in 1769 with the arrival of the first Spanish missionaries. -

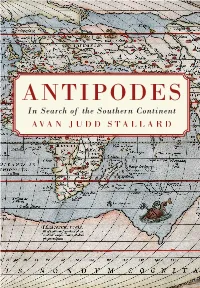

Antipodes: in Search of the Southern Continent Is a New History of an Ancient Geography

ANTIPODES In Search of the Southern Continent AVAN JUDD STALLARD Antipodes: In Search of the Southern Continent is a new history of an ancient geography. It reassesses the evidence for why Europeans believed a massive southern continent existed, About the author and why they advocated for its Avan Judd Stallard is an discovery. When ships were equal historian, writer of fiction, and to ambitions, explorers set out to editor based in Wimbledon, find and claim Terra Australis— United Kingdom. As an said to be as large, rich and historian he is concerned with varied as all the northern lands both the messy detail of what combined. happened in the past and with Antipodes charts these how scholars “create” history. voyages—voyages both through Broad interests in philosophy, the imagination and across the psychology, biological sciences, high seas—in pursuit of the and philology are underpinned mythical Terra Australis. In doing by an abiding curiosity about so, the question is asked: how method and epistemology— could so many fail to see the how we get to knowledge and realities they encountered? And what we purport to do with how is it a mythical land held the it. Stallard sees great benefit gaze of an era famed for breaking in big picture history and the free the shackles of superstition? synthesis of existing corpuses of That Terra Australis did knowledge and is a proponent of not exist didn’t stop explorers greater consilience between the pursuing the continent to its sciences and humanities. Antarctic obsolescence, unwilling He lives with his wife, and to abandon the promise of such dog Javier. -

Spanish Friar Antonio De La Ascension, Who Accompanied Sebastian

In 1510, the Spanish writer Garci Ordonez de Montalvo wrote Las sergas de Esplandian (The Exploits of Esplandian) in which he described an island of riches ruled by an Amazon Queen. "Know that to the right hand of the Indies was an island called California, very near to the region of the Terrestrial Paradise, which was populated by black women, without there being any men among them, that almost like the Amazons was their style of living. These were of vigorous bodies and The Warrior Queen Calafia strong and ardent hearts and of great strength …” “They dwelt in caves very well hewn; they had many ships in which they went out to other parts to make their forays, and the men they seized they took with them, giving them their deaths … And some times when they had peace with their adversaries, they intermixed … and there were carnal unions from which many of them came out pregnant, and if they gave birth to a female they kept her, and if they gave birth to a male, then he was killed…” “There ruled on that island of California, a queen great of body, very beautiful for her race … desirous in her thoughts of achieving great things, valiant in strength, cunning in her brave heart, more than any other who had ruled that kingdom before her...Queen Calafia." The novel was highly influential in motivating Hernan Cortez and other explorers in the discovery of the "island", which they believed lay along the west coast of North America. 1620 – Spanish Friar Antonio de la Ascension, who accompanied Sebastian Vizcaino on his West Coast expedition of 1602-03, drew the first map depicting California as an island. -

The NATIONAL FORESTS of CALIFORNIA Miscellaneous Circular No

The NATIONAL FORESTS OF CALIFORNIA Miscellaneous Circular No. 94 1927 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE Washington, D.C. TABLE OF CONTENTS Forests and public opinion Spanish California knew little of the forests Development of conservation National forest resources Timber Water Forage Recreation Wild life Administration of national forests National forest receipts Roads and trails Forest fires Appendix List of national forests with headquarters and net area National forests, parks, and monuments State parks Forest statistics, State of California Estimated stand of Government timber in national forests of California Timber cut in California, 1924 Production of lumber in California, 1923 and 1924 Consumption of lumber in California, 1920, 1922, 1923, and 1924 Grazing, national forests of California Hydroelectric power from streams in California Irrigated lands, State of California Farming, State of California Fire record, State of California Fire record, national forests of California Trees of California Six rules for preventing fire in the forests ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE March 12, 1927 Secretary of Agriculture W. M. JARDINE. Assistant Secretary R. W. DUNLAP. Director of Scientific Work A. F. WOODS. Director of Regulatory Work WALTER G. CAMPBELL. Director of Extension Work C. W. WARBURTON. Director of Information NELSON ANTRIM CRAWFORD. Director of Personnel and Business Administration W. W. STOCKBERGER. Solicitor R. W. WILLIAMS. Weather Bureau CHARLES F. MARVIN, Chief. Bureau of Agricultural Economics LLOYD S. TENNY, Chief. Bureau of Animal Industry JOHN R. MOHLER, Chief. Bureau of Plant Industry WILLIAM A. TAYLOR, Chief. Forest Service W. B. GREELEY, Chief. Bureau of Chemistry C. A. BROWNE, Chief. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of SONORA (Vers

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SONORA (Vers. 14 May 2019) © Richard C. Brusca topographically, ecologically, and biologically NOTE: Being but a brief overview, this essay cannot diverse. It is the most common gateway state do justice to Sonora’s long and colorful history; but it for visitors to the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of hopefully provides a condensed introduction to this California). Its population is about three million. marvelous state. Readers with a serious interest in Sonora should consult the fine histories and The origin of the name “Sonora” is geographies of the region, many of which are cited in unclear. The first record of the name is probably the References section. The topic of Spanish colonial that of explorer Francisco Vásquez de history has a rich literature in particular, and no Coronado, who passed through the region in attempt has been made to include all of those 1540 and called part of the area the Valle de La citations in the References (although the most targeted and comprehensive treatments are Sonora. Francisco de Ibarra also traveled included). Also see my “Bibliography on the Gulf of through the area in 1567 and referred to the California” at www.rickbrusca.com. All photographs Valles de la Señora. by R.C. Brusca, unless otherwise noted. This is a draft chapter for a planned book on the Sea of Cortez; Four major river systems occur in the state the most current version of this draft can be of Sonora, to empty into the Sea of Cortez: the downloaded at Río Colorado, Río Yaqui, Río Mayo, and http://rickbrusca.com/http___www.rickbrusca.com_ind massive Río Fuerte. -

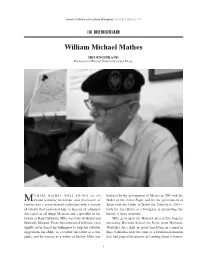

William Michael Mathes

Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 33, No. 1 (2013) | pp. 1–7 IN MEMORIAM William Michael Mathes IRIS ENGSTRAND Professor of History, University of San Diego ichael mathes, well known as an honored by the government of Mexico in 1985 with the Maward-winning historian and professor of Order of the Aztec Eagle and by the government of history, was a many-faceted individual with a variety Spain with the Order of Isabel the Catholic in 2005— of talents that endeared him to legions of admirers. both for his efforts as a foreigner in promoting the An expert in all things Mexican and a specialist in the history of those countries. history of Baja California, Mike was truly bicultural and Mike grew up in the Hancock area of Los Angeles, flawlessly bilingual.T hose who interacted with him, even attending Harvard School for Boys (now Harvard- slightly, never forgot his willingness to help, his valuable Westlake). As a child, he spent time living on a ranch in suggestions, his ability as a teacher, his talent as a tour Baja California near the ruins of a Dominican mission guide, and his success as a writer of history. Mike was that had piqued his interest in learning about a remote 1 2 Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 33, No. 1 (2013) area of the peninsula. Always a student of history, he mission trail spanning Baja and Alta California. His work received his B.A. from Loyola Marymount University, in these areas continues to be carried out by those who his M.A. -

California History Online

Chapter 1: The Physical Setting Regions and Landforms: Let's take a trip The land surface of California covers almost 100 million acres. It's the third largest of the states; only Alaska and Texas are larger. Within this vast area are a greater range of landforms, a greater variety of habitats, and more species of plants and animals than in any area of comparable size in all of North America. California Coast The coastline of California stretches for 1,264 miles from the Oregon border in the north to Mexico in the south. Some of the most breathtaking scenery in all of California lies along the Pacific coast. More than half of California's people reside in the coastal region. Most live in major cities that grew up around harbors at San Francisco Bay, San Diego Bay and the Los Angeles Basin. San Francisco Bay San Francisco Bay, one of the finest natural harbors in the world, covers some 450 square miles. It is two hundred feet deep at some points, but about two-thirds is less than twelve feet deep. The bay region, the only real break in the coastal mountains, is the ancestral homeland of the Ohlone and Coast Miwok Indians. It became the gateway for newcomers heading to the state's interior in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Tourism today is San Francisco's leading industry. San Diego Bay A variety of Yuman-speaking people have lived for thousands of years around the shores of San Diego Bay. European settlement began in 1769 with the arrival of the first Spanish missionaries. -

Baja California Islands Flora & Vertebrate Fauna

BAJA CALIFORNIA ISLANDS FLORA & VERTEBRATE FAUNA BIBLIOGRAPHY Mary Frances Campana This annotated bibliography covers the published literature on the flora and vertebrate fauna of the islands surrounding the Baja California peninsula. While comprehensive, it cannot claim to be exhaustive; however, Biological Abstracts and Zoological Record were searched extensively, back to the beginning of those indexes. With few exceptions, the author has examined either the materials themselves or abstracts. The bibliography is annotated, not abstracted. The descriptor field lists the islands mentioned in the work, or the phrases "Gulf Islands" and "Pacific Islands". The bibliography does not include Guadalupe, Socorro, the Tres Marias or other outlying islands. It contains few references to pinniped populations, and none to fish, insects or invertebrates since it is limited to vertebrate species and the terrestrial habitat. It does not cover the Mexican or Latin American literature on the islands to any great degree. Last Updated: July, 1997 The reptiles of Western North America Van Denburgh, J. Occasional Papers, California Academy of Sciences 10. 1922. SUBJECT DESCRIPTORS: Pacific Islands, Gulf Islands ANNOTATION: Tables listing descriptions, locations, distribution records of each species. Includes index, plate records of each species. The amphibians of Western North America Slevin, J.R. Occasional Papers, California Academy of Sciences 16. 1928. SUBJECT DESCRIPTORS: Gulf Islands, Cedros ANNOTATION: "No amphibians found on islands in the Gulf"; Cerros (Cedros) has Hyla regilla; description, location of species; index, plates Investigations in the natural history of Baja California Wiggins, I.L. Proceedings, California Academy of Sciences 30(1): 1 45. 1962. SUBJECT DESCRIPTORS: Espiritu Santo, Partida ANNOTATION: Records findings of various field trips in different seasons; some collection of snakes and plants, other reptiles; indicates much work on all islands in area needs to be done A history of exploration for vertebrates on Cerralvo Island, Baja California Banks, R.C.