Or When Do Jesus and the Apostles Really Get Mad?)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"The Great Commission from Calvin to Carey," Evangel 14:2

MISSION MISSION MISSION The Great Commission from Calvin to Carey R. E. DAVIES Just over two hundred years ago the Baptist, William Martin Bucer, the Strasbourg Reformer is con Carey, after repeated efforts was finally successful in cerned that ministers and elders should 'seek the lost', stirring up his fellow Baptists to do something about but by this he means those non-believers who attend world missions. He preached, argued, wrote, and the local church. Thus he says: eventually went as the first missionary of the newly formed Baptist Missionary Society. Very soon other What Christians in general and the civil authorities similar societies were formed-the London Missionary neglect to do with respect to seeking the lost lambs, Society and the Church Missionary Society being the this the elders of the Church shall undertake to first among many. make good in every possible way. And though they It seems an amazing fact that, although the Protestant do not have an apostolic call and command to go Reformation had begun nearly three hundred years to strange nations, yet they shall not in their several previously, Protestants by-and-large had not involved churches ... permit anyone who is not associated with the congregation of Christ to be lost in error themselves in the task of world evangelization. There 2 were exceptions, as we shall see, but in general this (Emphasis added). remains true. Calvin in his comments on Matthew 28 in his Harmony There were a number of reasons for this, some of the Four Evangelists says nothing one way or the valid, others less so, but one main reason for Protestant other on the applicability of the Great Commission to inaction was the widespread view that the Great the church of his own day. -

The Twelve Apostles Lesson 8 Study Notes Philip

f The Twelve Apostles Lesson 8 Study Notes Philip: The Apostle Who Was Slow-Witted Simon the Canaanite: The Apostle Who Was A Revolutionist Text: John 1:43-45. John 1:43 The day following Jesus would go forth into Galilee, and findeth Philip, and saith unto him, Follow me.44 Now Philip was of Bethsaida, the city of Andrew and Peter. 45 Philip findeth Nathanael, and saith unto him, We have found him, of whom Moses in the law, and the prophets, did write, Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph. Introduction: Philip is always listed as the fifth person in the list of the Apostles. While he may have not been as prominent as the first four men listed; nevertheless, he seems to be the head of the second grouping of the disciples. We must remember that God is of no respecter of persons so, Philip is not to be considered to be of less importance. Although Philip is mentioned in the four complete lists of the twelve (Matt. 10:3; Mark 3:18; Luke 6:14; Acts 1:13), it is interesting to observe that John is the only writer to tell us all that is to be said about Philip, yet he is the only one out of the four evangelists who does not quote the list. The first three evangelists give us his name and acquaint us with the fact that he was an apostle, but John loses sight of the dignity of the office that Philip filled and gives us a profile of the man himself with his own individualities and peculiarities. -

Emblems of the Four Evangelists

Emblems of the Four Evangelists THE winged living figures, symbols of the evangelists, which are most frequently met with, and which have ever been most in favour with Early Christian artists, appear to have been used at a very early date. They are taken from the vision of Ezekiel and the Revelation of St. John. "The writings of St. Jerome," says Audsley, "in the beginning of the fifth century gave to artists’ authority for the appropriation of the four creatures to the evangelists," and for reasons which are there given at length. ST. MATTHEW: Winged Man, Incarnation.—To St. Matthew was given the creature in human likeness, because he commences his gospel with the human generation of Christ, and because in his writings the human nature of Our Lord is more dwelt upon than the divine. ST. MARK: Winged Lion, The Resurrection.—The Lion was the symbol of St. Mark, who opens his gospel with the mission of John the Baptist, "the voice of one crying in the wilderness." He also sets forth the royal dignity of Christ and dwells upon His power manifested in the resurrection from the dead. The lion was accepted in early times as a symbol of the resurrection because the young lion was believed always to be born dead, but was awakened to vitality by the breath, the tongue, and roaring of its sire. ST. LUKE: Winged Ox, Passion.—the form of the ox, the beast of sacrifice, fitly sets forth the sacred office, and also the atonement for sin by blood, on which, in his gospel, he particularly dwells. -

The Lord of the Sabbath

The Lord of the Sabbath Matthew 12:1-8 Mark 2:23-28 Unpopular Positions • Bible can be understood (Ephesians 3:3-5; 5:17; 2 Timothy 3:16-17). • Responsible for misunderstanding (2 Peter 3:16-18). • Stand for the truth (Titus 1:9-11; Jude 3). • Prohibits full fellowship with world (2 Corinthians 6:12-17). • Leads to division in church (1 Corinthians 5:4-13). • Causes divisions even in families (Matthew 10:21-42). Excused to Disobey In an article entitled "The Exception-Making God," brother Michael Hall writes, "The hunger of David and his men, the need of Jesus and His 12- member staff, the need of the physically maimed who sought to be healed on the Sabbath (Luke 13:11-17), etc., are all examples of human need that necessitated an exception to some rule . God is flexible about His rules because he does care about men. That's why the Bible is not a legal document, but a book of principles . everything is not as cut and dry as you might think!" (Michael Hall, “The Exception-Making God”, Ensign, January 1978, pp. 14,13). “In other words, human need is a higher law than religious rules and regulations. Or, to put it more exactly, love is the highest law in the universe and supersedes all other regulations. And love demands that human need must be met, even if some legal technicalities have to be laid aside in the process. … It is obvious that this concept of true religion as consisting of a right attitude rather than ritual acts was central to Jesus’ thinking.” (Beacon Bible Commentary, Vol. -

SYMBOLS Te Holy Apostles & Evangelists Peter

SYMBOLS Te Holy Apostles & Evangelists Peter Te most common symbol for St. Peter is that of two keys crossed and pointing up. Tey recall Peter’s confession and Jesus’ statement regarding the Office of the Keys in Matthew, chapter 16. A rooster is also sometimes used, recalling Peter’s denial of his Lord. Another popular symbol is that of an inverted cross. Peter is said to have been crucifed in Rome, requesting to be crucifed upside down because he did not consider himself worthy to die in the same position as that of his Lord. James the Greater Tree scallop shells are used for St. James, with two above and one below. Another shows a scallop shell with a vertical sword, signifying his death at the hands of Herod, as recorded in Acts 12:2. Tradition states that his remains were carried from Jerusalem to northern Spain were he was buried in the city of Santiago de Compostela, the capital of Galicia. As one of the most desired pilgrimages for Christians since medieval times together with Jerusalem and Rome, scallop shells are often associated with James as they are often found on the shores in Galicia. For this reason the scallop shell has been a symbol of pilgrimage. John When shown as an apostle, rather than one of the four evangelists, St. John’s symbol shows a chalice and a serpent coming out from it. Early historians and writers state that an attempt was made to poison him, but he was spared before being sent to Patmos. A vertical sword and snake are also used in some churches. -

The Four-Fold Gospel

The Four-Fold Gospel Author(s): McGarvey, J. W. Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: This mixture of gospel harmony (a comparison of identical stories from each of the gospels, placed in chronological or- der) and commentary (a verse-by-verse analysis of a pas- sage) by John William McGarvey is a highly technical but incomparably useful guide to the biblical Gospels. McGarvey, a serious student of the Bible and author of many other commentaries, is at his best here in the unique blend. Users should be sure to read the introductory sections in order to understand the abbreviations, symbols, and set-up of the volume to avoid confusion and to get optimal use from the source. This reference is a wonderful expansion of Gospel commentaries, and is one of the only books of its kind. Abby Zwart CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: The Bible New Testament Special parts of the New Testament i Contents A Harmony of the Gospels 1 Introduction. 2 Preserving the Text. 3 To Distinguish the Gospels. 4 Combination Illustrated. 5 Lesser and Fuller Forms. 6 Sections and Subdivisions. 7 Four Points of Economy. 8 Care in Preparing this Work. 9 An Object in View. 10 The Period of Christ's Life Prior to His Ministry. 11 Luke I. 1-4. 12 John I. 1-18. 13 Matt. I. 1-17. 15 Luke III. 23-38. 17 Luke I. 5-25. 18 Luke I. 26-38. 22 Luke I. 39-56. 24 Luke I. 57-80. 26 Matt. I. 18-25. 28 Luke II. -

The Gospel of Mark

The Gospel of Mark A Living Word Independent Bible Study The Gospel of Mark Part 6 Mark 2:23-3:6 A Living Word Independent Bible Study We’ve now seen Jesus facing conflict over: Forgiving the paralytic’s sins REVIEW Eating with the wrong people Not fasting of In this lesson, we will see two new stories about conflict, both Mar k 1:1-2:22 related to the observance of the Sabbath. We have also seen the way this conflict is escalating: in 2:7, Jesus’ opponents simply questioned him in their hearts in 2:15, Jesus’ opponents asked the disciples about their behavior In this lesson, we will see Jesus’ opponents question Jesus himself for the first time, and then, we will see Jesus’ opponents laying in wait for him, and then plotting how they might kill him. “Sabbath” Mark 2:23 ( NIV) The Sabbath was instituted by God. It is part of Creation week: One Sabbath Jesus was Genesis 2:2-4 – “By the seventh day God had finished the work he had going through the grain- been doing; so on the seventh day he rested from all his work. Then God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it he rested from all the work of creating fields and as his disciples that he had done.” (NIV) walked along, they began It is set within the Ten Commandments: to pick some heads of Exodus 20:8-10 – “Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy, Six days grain. you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the LORD your God. -

He Sanctuary Series

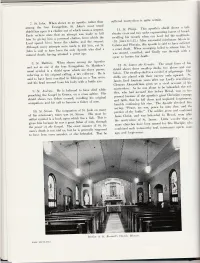

T S S HE ANCTUARY ERIES A Compilation of Saint U News Articles h ON THE g Saints Depicted in the Murals & Statuary of Saint Ursula Church OUR CHURCH, LIVE IN HRIST, A C LED BY THE APOSTLES O ver the main doors of St. Ursula Church, the large window pictures the Apostles looking upward to an ascending Jesus. Directly opposite facing the congregation is the wall with the new painting of the Apostles. The journey of faith we all make begins with the teaching of the Apostles, leads us through Baptism, toward altar and the Apostles guiding us by pulpit and altar to Christ himself pictured so clearly on the three-fold front of the Tabernacle. The lively multi-experiences of all those on the journey are reflected in the multi-colors of the pillars. W e are all connected by Christ with whom we journey, He the vine, we the branches, uniting us in faith, hope, and love connected to the Apostles and one another. O ur newly redone interior, rededicated on June 16, 2013, was the result of a collaboration between our many parishioners, the Intelligent Design Group (architect), the artistic designs of New Guild Studios, and the management and supervision of many craftsmen and technicians by Landau Building Company. I n March 2014, the Landau Building Company, in a category with four other projects, won a first place award from the Master Builders Association in the area of “Excellence in Craftsmanship by a General Contractor” for their work on the renovations at St. Ursula. A fter the extensive renovation to the church, our parish community began asking questions about the Apostles on the Sanctuary wall and wishing to know who they were. -

Jesus Wow! Series Part 13 Jesus, Lord of the Sabbath Mark 2:23 – 3

Jesus Wow! Series Part 13 Jesus, Lord of The Sabbath Mark 2:23 – 3:6 Pastor Andrew Neville 5/7/20 Sermon Summary Pastor Andrew’s opening anecdote occurred when, as a young Christian, he was savagely beaten (spiritually) by a woman of the Jehovah Witness persuasion. At that time Andrew had no answer for her avalanche of knowledge that Jesus was not God. It was during a reading of today’s passage that a light suddenly shone into his disquieted soul some many months later. So far in the gospel of Mark, we have looked at three incidents in Jesus’ ministry that were controversial; today we will look at two more. In each case, Jesus’ divinity is questioned – then displayed in his answers. To the Pharisees, Jesus appeared to be dismissive of the Law in its application. The Pharisees were out to trap Jesus – He wasn’t the Messiah they wanted. The two stories in today’s sermon have issues that were a no-go to The Pharisees – working and healing on the Sabbath. The Sabbath was a big deal to the Jews. The many rules for observing the Sabbath had been laid down over centuries and had their basis in Exodus 20:8-11: “Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy. Six days you shall labour and do all your work, but the 7th day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, neither you nor your son or daughter, nor your manservant or maidservant, nor your animals, nor the alien within your gates. -

The Gospels and the Four Evangelists the Gospels and the Four Evangelists

Resources for Teaching our budding rocks of faith The Gospels and the four Evangelists Activities for teaching young Orthodox Christian children about the Gospels and their authors. COPYRIGHT © 2019 Orthodox Pebbles © 2019 Orthodox COPYRIGHT The icons on this page can be printed, cut out, and glued on the worksheet of the following page. Russian icon from the first quarter of XVIII century, Iconostasis of Trans- figuration church, Kizhi monastery, Karelia, Russia [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia. org/wiki/File:Matthew_Evange- list.jpg APOSTLE AND EVANGELIST MATTHEW FEAST DAY: Matthew is one of the Twelve Apostles. He was Where in the world? initially a publican, a tax-collector. At the time, tax-collectors were very much hated because they often took advantage of people. Upon meet- ing our Lord, he greatly repented and immedi- ately followed Him. He preached the Gospel in Palestine, Syria, Media, Persia, and Ethiopia. In Ethiopia he worked many miracles by the Grace of God, and baptized thousands. At the end, he was tortured and put to death for his Christian faith, thus becoming a martyr. by Map of the world single color FreeVectorMaps. How can I be like the Apostle and Evangelist Matthew? My prayer to the Apostle and Evangelist Matthew: COPYRIGHT © 2019 Orthodox Pebbles © 2019 Orthodox COPYRIGHT CALENDAR CARD For instructions on how to make a Saint card calendar, please visit our November Saints webpage at orthodoxpebbles.com/saints/november-saints. Saint card Feast date Evangelist Matthew Saint Matthew is one of the Twelve Apos- tles. He was initially a tax-collector. -

Why Four Gospels? (Continue)

PRINCIPLES IN SERVING GOD NEW TESTAMENT THE FOUR GOSPELS THE FOUR GOSPELS MEANING OF THE WORD ‘GOSPEL’ • Gospel means the good news or the good tidings. • Good tidings are that God sent His only begotten Son into the world to save the believers. • The Arabic word equivalent to gospel is ‘Bishara’, and means an Apostolic Book regarding the life of the Lord Christ on earth. WHY FOUR GOSPELS? (CONTINUE) • Similarly, each of the four Gospel writers looks at Jesus from his own distinct angle. • The four Gospels are not biographies in the modern sense. • A large portion of Jesus’ life is skipped over, and all four Gospels give a significant amount of their writing to His passion week (e.g. Mark 11-16 covers the week leading to the cross and resurrection). WHY FOUR GOSPELS? • There is no one definitive biography of Jesus Christ in existence, but rather four separate and complementary accounts. • Why? Because a picture, or portrait, is more complete when viewed from several different angles. WHY FOUR GOSPELS? • The biography of an important person is not really complete unless we have accounts from various perspectives, Jesus is not just an important person, He is the word of God, He is God. • Different persons would see things from a different viewpoint and thus give us a little different slant on his life. THE FOUR GOSPELS Matthew Mark Luke John 28 16 24 21 MATTHEW • Matthew is one of four Gospels that records the life of Jesus Christ. Matthew, the Hebrew tax collector, writes for the Hebrew mind. • His emphasis on the Old Testament preparation for the Gospel makes it an ideal "bridge" from the Old to the New Testament. -

7. St. John. When Shown As an Apostle, Rather Than

is quite certaitr' apostle' lather than su[ielecl tlrartrrtloltl 1. St ..1 oltn. When shorrn as atr lllost usuirl snrong the loul l"r'aln-qelist.-t' St' John's shielcl sh"*s a tall' a sel'pellt' 11. 51. I'hitip' This aPostle's lrtrs upotl it a t'halice olrt of nhich issues o{ lrrea'l' shieirl artd trro sat:ks Iepresetrting It'ares attenlPt rr as ntaile to kiIi .lencler cross il"rit rtt iters statc thtrt an out' Lt'r'd Iet[ tlle rrru[titullt' fronr ivhir:h tht' ,",-otlilg ltis rerrrark rr'hen ilirrr lrr gir irlg lrirrr a 1lt'isoned t'halitle' ntissiotralr ]alrols irr serpent' tr'. 1,r?n 6:l'I.i. i d{ter suc':essIul l,.,.rl .1,nre.l hirrr: lrente the chalice and the ltart (lalatia ancl PIrlrgia' this apostle is sair] to 'tll'let'''i tttatll attetrtilt's rtel'e tnarle lo kijl hirrL" iet St' ii'' .,,\lrh,rtrgh Wheu tt't'u',uing iailetl to silerrt'e ltirrr' l'een the oltlr :\postle rt'h" rliecl ir a , r'Lrel tleatlt. 1,,1,,, i. tni.l t,, lrar e t utt tltr.ugll rlitlr r u as stotrecl. cruci{ietl' ancl f inalh nalulaI rleatlt" Ilaving attainecl a great age' sl)eat'[() hasten his death' tiie \postles li..!1. llttttltett. When shol'n anr()rlEi 'fhe usual 1'rrtrr lti' St' }latllrel's 12. Sr. Jutrtes tlte Gre:uter' "l lrrcl nril ils {)lle oi the four Evangelists' itltor t" ittttl otr''- slrielrl slrou s three e.'ca[1op 'thells' trt'o a shielcl riporr w hi<'h at'e.- thter: puI'ses' usual si trrlrol is 'l-he is a sr rlrbol ol pilgr:irrrage' l-h'' a tax coller:tot" He i* l,el,rrr.