Annotated List of the Mammals of Nova Scotia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rare Vascular Plant Surveys in the Polletts Cove and Lahave River Areas of Nova Scotia

Rare Vascular Plant Surveys in the Polletts Cove and LaHave River areas of Nova Scotia David Mazerolle, Sean Blaney and Alain Belliveau Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre November 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was funded by the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources, through their Species at Risk Conservation Fund. The Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre appreciates the opportunity provided by the fund to have visited these botanically significant areas. We also thank Sean Basquill for mapping, fieldwork and good company on our Polletts Cove trip, and Cape Breton Highlands National Park for assistance with vehicle transportation at the start of that trip. PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS All photographs included in this report were taken by the authors. 1 INTRODUCTION This project, funded by the Nova Scotia Species at Risk Conservation Fund, focused on two areas of high potential for rare plant occurrence: 1) the Polletts Cove and Blair River system in northern Cape Breton, covered over eight AC CDC botanist field days; and 2) the lower, non-tidal 29 km and selected tidal portions of the LaHave River in Lunenburg County, covered over 12 AC CDC botanist field days. The Cape Breton Highlands support a diverse array of provincially rare plants, many with Arctic or western affinity, on cliffs, river shores, and mature deciduous forests in the deep ravines (especially those with more calcareous bedrock and/or soil) and on the peatlands and barrens of the highland plateau. Recent AC CDC fieldwork on Lockhart Brook, Big Southwest Brook and the North Aspy River sites similar to the Polletts Cove and Blair River valley was very successful, documenting 477 records of 52 provincially rare plant species in only five days of fieldwork. -

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island 381 a Different View from The

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island A different view from the sea: placenaming on Cape Breton Island William Davey Cape Breton University Sydney NS Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT : George Story’s paper A view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming suggests that there are other, complementary methods of collection and analysis than those used by his colleague E. R. Seary. Story examines the wealth of material found in travel accounts and the knowledge of fishers. This paper takes a different view from the sea as it considers the development of Cape Breton placenames using cartographic evidence from several influential historic maps from 1632 to 1878. The paper’s focus is on the shift names that were first given to water and coastal features and later shifted to designate settlements. As the seasonal fishing stations became permanent settlements, these new communities retained the names originally given to water and coastal features, so, for example, Glace Bay names a town and bay. By the 1870s, shift names account for a little more than 80% of the community names recorded on the Cape Breton county maps in the Atlas of the Maritime Provinces . Other patterns of naming also reflect a view from the sea. Landmarks and boundary markers appear on early maps and are consistently repeated, and perimeter naming occurs along the seacoasts, lakes, and rivers. This view from the sea is a distinctive quality of the island’s names. Keywords: Canada, Cape Breton, historical cartography, island toponymy, placenames © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction George Story’s paper The view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming “suggests other complementary methods of collection and analysis” (1990, p. -

Common Language(R) Geographical Codes Canada

BELLCORE PRACTICE BR 751-401-166 ISSUE 17, FEBRUARY 1999 COMMON LANGUAGE® Geographical Codes Canada - Nova Scotia (NS) BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY This document contains proprietary information that shall be distributed, routed or made available only within Bellcore, except with written permission of Bellcore. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE Possession and/or use of this material is subject to the provisions of a written license agreement with Bellcore. Geographical Codes Canada - Nova Scotia (NS) BR 751-401-166 Copyright Page Issue 17, February 1999 Prepared for Bellcore by: R. Keller For further information, please contact: R. Keller (732) 699-5330 To obtain copies of this document, Regional Company/BCC personnel should contact their company’s document coordinator; Bellcore personnel should call (732) 699-5802. Copyright 1999 Bellcore. All rights reserved. Project funding year: 1999. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. ii LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-166 Geographical Codes Canada - Nova Scotia (NS) Issue 17, February 1999 Trademark Acknowledgements Trademark Acknowledgements COMMON LANGUAGE is a registered trademark and CLLI is a trademark of Bellcore. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE iii Geographical Codes Canada - Nova Scotia (NS) BR 751-401-166 Trademark Acknowledgements Issue 17, February 1999 BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. iv LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-166 Geographical Codes Canada - Nova Scotia (NS) Issue 17, February 1999 Table of Contents COMMON LANGUAGE Geographic Codes Canada - Nova Scotia (NS) Table of Contents 1. -

Hunting Summary 2016

2016 NOVA SCOTIA HUNTING & FURHARVESTING SUMMARY OF REGULATIONS Cover photo by Travis MacKinnon 2015 Trail Camera winner This is a summary prepared for the information and convenience of anyone who plans to hunt or trap in Nova Scotia. The full copy of the Wildlife Act and Regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpreting and applying the law. These laws are subject to change at any time and are available online at novascotia.ca/natr/wildlife/laws/actsregs.asp For detailed information please see our website at novascotia.ca/natr/hunt Report illegal hunting and/or trapping to your local Natural Resources Office or call 1-800-565-2224 Honourable Lloyd Hines Minister Frank Dunn Deputy Minister Please help the environment. Recycle this book. 2 Message from the Minister This booklet outlines fees, bag limits, season dates, a summary of regulations, and other information for the 2016 hunting season. The additional licence and season for hunting deer with muzzleloaders and archery equipment will continue this year. It has increased the number of hunting days available for Nova Scotia deer hunters, with little impact on the deer harvest. The Special Youth Season for hunting deer will take place from October 14–22. Young Nova Scotians may also participate in Waterfowler Heritage Day on Saturday, September 17th. Each year, these special hunts provide qualified young hunters with wonderful opportunities to be introduced to hunting and gain experience under the supervision of experienced adult hunters. In the fall of 2015, we introduced limited Sunday hunting to Nova Scotia on the two Sundays immediately following the last Friday in October. -

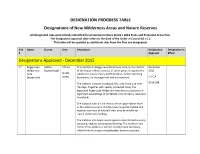

DESIGNATION PROGRESS TABLE Designations of New Wilderness Areas and Nature Reserves

DESIGNATION PROGRESS TABLE Designations of New Wilderness Areas and Nature Reserves All designated sites were initially identified for protection in Nova Scotia’s 2013 Parks and Protected Areas Plan. The designation approval date refers to the date of the Order in Council (O.I.C.). This table will be updated as additional sites from the Plan are designated. Site Name County Area Description Designation Designation in # Approval Effect Designations Approved - December 2015 17 Boggy Lake Halifax, 973 ha This addition to Boggy Lake Wilderness Area, in the interior December Wilderness Guysborough of the Eastern Shore, consists of seven parts. It expands the 2015 Area (2,405 wilderness area to nearly 4,700 hectares, while improving (expansion) acres) boundaries for management and enforcement. O.I.C.# The addition includes hardwood hills, lake shore and river 2015-388 frontage. Together with nearby protected lands, the expanded Boggy Lake Wilderness Area forms a provincially- significant assemblage of protected river corridors, lakes and woodlands. The addition adds a 9 km section of the upper Moser River to the wilderness area. It helps protect aquatic habitat and expands corridors of natural forest used by wildlife for travel, shelter and feeding. The addition also helps secure opportunities for backcountry canoeing, angling, camping and hunting. The northern two- thirds of the addition is within Liscomb Game Sanctuary, which limits hunting to muzzleloader, bow or crossbow. Site Name County Area Description Designation Designation in # Approval Effect Forest access roads along the western and northern sides of the addition provide access. Vehicle use to access points at Long Lake and Bear Lake is also unaffected. -

(Coleoptera, Staphylinidae) in the Maritime Provinces of Canada

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 46: 15–39Contributions (2010) to the knowledge of the Aleocharinae (Coleoptera, Staphylinidae)... 15 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.46.413 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.pensoftonline.net/zookeys Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Contributions to the knowledge of the Aleocharinae (Coleoptera, Staphylinidae) in the Maritime Provinces of Canada Christopher G. Majka1, Jan Klimaszewski2 1 Nova Scotia Museum, 1747 Summer Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3H 3A6 2 Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Laurentien Forestry Centre, 1055 rue du P.E.P.S., PO Box 10380, Stn. Sainte-Foy, Québec, QC, Canada G1V 4C7 Corresponding author: Christopher G. Majka ([email protected]) Academic editor: Volker Assing | Received 16 February 2009 | Accepted 16 April 2010 | Published 17 May 2010 Citation: Majka CG, Klimaszewski J (2010) Contributions to the knowledge of the Aleocharinae (Coleoptera, Staphyli- nidae) in the Maritime Provinces of Canada. ZooKeys 46: 15–39. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.46.413 Abstract Since 1970, 203 species of Aleocharinae have been recorded in the Maritime Provinces of Canada, 174 of which have been reported in the past decade. Th is rapid growth of knowledge of this hitherto neglected subfamily of rove beetles occasions the present compilation of species recorded in the region together with the chronology of their discovery. Sixteen new provincial records are reported, twelve from Nova Scotia, one from New Brunswick, and three from Prince Edward Island. Seven species, including Oxypoda chantali Klimaszewski, Oxypoda perexilis Casey, Myllaena cuneata Notman, Placusa canadensis Klimasze- wski, Geostiba (Sibiota) appalachigena Gusarov, Lypoglossa angularis obtusa (LeConte), and Trichiusa postica Casey [tentative identifi cation] are newly recorded in the Maritime Provinces, one of which,Myllaena cuneata, is newly recorded in Canada. -

19.09.19 Liste Des Villes Et Zones NS.Xlsx

Ville -City Zone Ville -City Zone Ville -City Zone A A A A And D Trailer Park 2 Alpine Ridge 4 Armstrong Lake 2 Aalders Landing 2 Alton 2 Arnold 3 Abercrombie 2 Amherst 2 Ashby 4 Aberdeen 4 Amherst Head 2 Ashdale 2 Abram River 3 Amherst Point 2 Ashdale (West Hants) 2 Abrams River 3 Amherst Shore 2 Ashfield 4 Acaciaville 3 Amirault Hill 3 Ashfield Station 4 Academy 2 Amiraults Corner 3 Ashmore 3 Addington Forks 2 Amiraults Hill 3 Askilton 4 Admiral Rock 2 Anderson Mountain 2 Aspen 2 Advocate Harbour 2 Angevine Lake 2 Aspotogan 3 Africville 1 Annandale 2 Aspy Bay 4 Afton 2 Annapolis 2 Athol 2 Afton Station 2 Annapolis Royal 2 Athol Road 2 Aikens 2 Annapolis Valley 2 Athol Station 2 Ainslie Glen 4 Annapolis, Subd. A 2 Atkinson 2 Ainslie Point 4 Annapolis, Subd. B 2 Atlanta 2 Ainslieview 4 Annapolis, Subd. C 2 Atlantic 3 Alba 4 Annapolis, Subd. D 2 Atwood Brook 3 Alba Station 4 Antigonish 2 Atwoods Brook 3 Albany 2 Antigonish Harbour 2 Atwood's Brook 3 Albany Cross 2 Antigonish Landing 2 Atwoods Brook Station 3 Albany New 2 Antigonish, Subd. A 2 Auburn 2 Albert Bridge 4 Antigonish, Subd. B 2 Auburndale 3 Albro Lake 1 Antrim 1 Auld Cove 2 Alder Plains 3 Apple River 2 Aulds Cove 2 Alder Point 4 Arcadia 3 Avondale (Pictou, Subd. B) 2 Alder River 2 Archibald 2 Avondale (West Hants) 2 Alderney Point 4 Archibalds Mill 2 Avondale Station 2 Aldershot 2 Ardness 2 Avonport 2 Aldersville 3 Ardoise 2 Avonport Station 2 Alderwood Acres 1 Argyle 2 Aylesford 2 Alderwood Trailer Court 1 Argyle 3 Aylesford East 2 Allains Creek 2 Argyle Head 3 Aylesford Lake -

2000 Conference at the Lord Nelson Hotel

COUNCIL FOR NORTHEAST HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY HALIFAX, 2000 LORD NELSON HOTEL OCTOBER 5-8 PROGRAMME AND ABSTRACTS COUNCIL FOR NORTHEAST HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY Officers Chair: Sherene Baugher Executive Vice Chair: Rebecca Yamin Vice-Chair: Wade Catts Secretary: Dena Doroszenko Treasurer: Sara Mascia Board Members Lysbeth Acuff Paul Huey Karen Metheney Charles Burke Terry Klein Timothy B. Riordan Lu Ann De Cunzo Ann-Eliza Lewis Programme Chairs Charles Burke Rob Ferguson Parks Canada Parks Canada [email protected] [email protected] Acknowledgements Mami Amirault Denise Hansen Andrea Richardson Lori Warren David Christianson Sharaine Jones Judith Shiers Milne David Williamson Katy Cottreau Earl Luffman Shiela Stevenson student volunteers Danny Dyke Hilary MacDonald Robert Strickland of Halifax West Jon Fowler Matthew Mosher Janet Stoddard Highschool Elizabeth Grzesik Laird Niven Colin Varley Aaron Hannah Stephen Powell Nancy Vienneau CNEHA2000 is jointly sponsored by the Nova Scotia Archaeology Society, Nova Scotia Museum and Parks Canada Agency. Logo This year's logo is a seventeenth-century bale seal. It was recovered from the Scottish occupation level (1629-1632) at Fort Anne National Historic Site during excavations for Parks Canada by Birgitta Wallace. On one side is the coat of arms for the port of Bristol. The other side bears a thistle, though not, apparently, from any Scottish connection. The archaeological context and the imagery are evocative of Nova Scotia's early history - it's maritime connections and its Scottish heritage from which we get both the name and flag of the province (drawings by Rion Microys for Parks Canada). IMPORTANT NOTES Welcome to Halifax and to the CNEHA 2000 conference at the Lord Nelson Hotel. -

Moose River Consolidated Phase 2 Project Nova Scotia, Canada NI 43-101 Technical Report

Moose River Consolidated Phase 2 Project Nova Scotia, Canada NI 43-101 Technical Report Report Authors Report Effective Date: 20 July, 2017 Mr Paul Staples, P.Eng. Mr Neil Schofield, MAIG Mr Marc Schulte, P.Eng. Mr Tracey Meintjes, P.Eng. Mr James Millard, P.Geo. Mr Jeff Parks, P.Geo. CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON I, Paul Staples, P.Eng. am employed as the Vice President and Global Practice Lead, Minerals and Metals with Ausenco Solutions Canada Inc. (Ausenco). This certificate applies to the technical report titled “Moose River Consolidated Phase 2 Project, Nova Scotia, Canada, NI 43-101 Technical Report” that has an effective date of 20 July, 2017 (the “technical report”). I am a registered Professional Engineer of Nova Scotia, membership number 4832. I graduated from Queens University in 1993 with a degree in Materials and Metallurgical Engineer. I have practiced my profession for 23 years. I have been directly involved in process operation, design and management from over 15 similar studies or projects including the 80 Mt/y Grasberg complex in Indonesia (1998-2003), the 20 Mt/y Lumwana Project in Zambia (2005-2007), the 26 Mt/y Constancia Project in Peru (2010-2015) and the 38 Mt/y Dumont feasibility study in Canada (2010-2016). As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43–101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (NI 43–101). I have visited the Moose River Consolidated Phase 2 Project on July 12, 2017. I am responsible for Sections 1.1 to 1.4, 1.9, 1.14 to 1.16, 1.18 to 1.19, 1.22 to 1.24; Section 2; Section 3; Section 4; Section 5; Section 13; Section 17; Section 18; Section 19; Section 21; Section 23; Section 24; Sections 25.1, 25.5, 25.9 to 25.10, 25.12 to 25.14, 25.16; Sections 26.1, 26.3; and Section 27 of the technical report. -

Ecoregions and Ecodistricts of Nova Scotia

Ecoregions and Ecodistricts of Nova Scotia K.T. Webb Crops and Livestock Research Centre Research Branch Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Truro, Nova Scotia I.B. Marshall Indicators and Assessment Office Environmental Quality Branch Environment Canada Hull, Quebec Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Environment Canada 1999 ~ Minister of Public Works and Government Services Cat. No. A42-65/1999E ISBN 0-662-28206-X Copies of this publication are available from: Crops and Livestock Research Centre Research Branch Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada P.O. Box 550, Banting Annex Nova Scotia Agricultural College Truro, Nova Scotia B2N 5E3 or Indicators and Assessment Office Environmental Quality Branch Environment Canada 351 St. Joseph Blvd. Hull, Quebec KIA OC3 Citation Webb, K.T. and Marshall, LB. 1999. Ecoregions and ecodistricts of Nova Scotia. Crops and Livestock Research Centre, Research Branch, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Truro, Nova Scotia; Indicators and Assessment Office, Environmental Quality Branch, Environment Canada, Hull, Quebec. 39 pp. and 1 map. CONTENTS PREFACE. v PREFACE. ., vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . vii IN'TRODUCTION 1 ECOSYSTEMS AND ECOLOGICAL LAND CLASSIFICATION 1 THE NATIONAL ECOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK AND NOVA SCOTIA 3 ECOLOGICAL UNITS . 4 Ecozones . 4 Ecoregions . _ . _ 4 Ecodistricts _ . _ . 4 ECOLOGICAL UNIT DESCRIPTIONS . 6 ATLANTIC MARITIME ECOZONE . _ . 6 MARITIME LOWLANDS ECOREGION (122) . 7 Pictou-Cumberland Lowlands Ecodistrict (504) . _ 7 FUNDY COAST ECOREGION (123) _ . 8 Chignecto-Minas Shore Ecodistrict (507) . _ . 9 North MountainEcodistrict(509) _ . _ 10 SOUTHWEST NOVA SCOTIA UPLANDS ECOREGION (124) 11 South Mountain Ecodistrict (510) 12 Chester Ecodistrict (511) . 12 Lunenburg Drumlins Ecodistrict (512) . 13 Tusket River Ecodistrict (513) . -

Arbitration Between Newfoundland & Labrador and Nova Scotia

ARBITRATION BETWEEN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR AND NOVA SCOTIA CONCERNING PORTIONS OF THE LIMITS OF THEIR OFFSHORE AREAS AS DEFINED IN THE CANADA-NOVA SCOTIA OFFSHORE PETROLEUM RESOURCES ACCORD IMPLEMENTATION ACT AND THE CANADA- NEWFOUNDLAND ATLANTIC ACCORD IMPLEMENTATION ACT AWARD OF THE TRIBUNAL IN THE SECOND PHASE Ottawa, March 26, 2002 Table of Contents Paragraph 1. Introduction (a) The Present Proceedings 1.1 (b) History of the Dispute lA (c) Findings of the Tribunal in the First Phase 1.19 (d) The Positions of the Parties in the Second Phase 1.22 2. The Applicable Law (a) The Terms of Reference 2.1 (b) The Basis of Title 2.5 (c) Applicability of the 1958 Geneva Convention on 2.19 the Continental Shelf (d) Subsequent Developments in the International Law 2.26 of Maritime Delimitation (e) The Offshore Areas beyond 200 Nautical Miles 2.29 (t) The Tribunal's Conclusions as to the Applicable Law 2.35 3. The Process of Delimitation: Preliminary Issues (a) The Conduct of the Parties 3.2 (b) The Issue of Access to Resources 3.19 4. The Geographical Context for the Delimitation: Coasts, Areas and Islands (a) General Description 4.1 (b) Identifying the Relevant Coasts and Area 4.2 (c) Situation of Offshore Islands 4.25 (i) S1.Pierre and Miquelon 4.26 (ii) S1.Paul Island 4.30 (iii) Sable Island 4.32 (iv) Other Islands Forming Potential Basepoints 4.36 5. Delimiting the Parties' Offshore Areas (a) The Initial Choice of Method 5.2 (b) The Inner Area 5A (c) The Outer Area 5.9 (d) From Cabot Strait Northwestward in the Gulf of S1.Lawrence 5.15 (e) Confirming the Equity of the Delimitation 5.16 AWARD Appendix - Technical Expert's Report 1 AWARD In the case concerning the delimitation of portions of the offshore areas between The Province of Nova Scotia and The Province of Newfoundland and Labrador THE TRIBUNAL Hon. -

Bicknell's Thrush (Catharus Bicknelli)

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Bicknell’s Thrush Catharus bicknelli in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 1999 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION DES ENDANGERED WILDLIFE IN ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: Please note: Persons wishing to cite data in the report should refer to the report (and cite the author(s)); persons wishing to cite the COSEWIC status will refer to the assessment (and cite COSEWIC). A production note will be provided if additional information on the status report history is required. COSEWIC 1999. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Bicknell’s thrush Catharus bicknelli in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. v + 43 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Nixon E. 1999. COSEWIC status report on the Bicknell’s thrush Catharus bicknelli in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Bicknell’s thrush Catharus bicknelli in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-43 pp. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation de la Grive de Bicknell au Canada. Cover illustration: Bicknell’s Thrush — J.