Comparing of the Amounts of Energy Released in Combustion Reactions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Energy Storage Technologies' Application

sustainability Review A Review of Energy Storage Technologies’ Application Potentials in Renewable Energy Sources Grid Integration Henok Ayele Behabtu 1,2,* , Maarten Messagie 1, Thierry Coosemans 1, Maitane Berecibar 1, Kinde Anlay Fante 2 , Abraham Alem Kebede 1,2 and Joeri Van Mierlo 1 1 Mobility, Logistics, and Automotive Technology Research Centre, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (A.A.K.); [email protected] (J.V.M.) 2 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Jimma Institute of Technology, Jimma University, Jimma P.O. Box 378, Ethiopia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-485659951 or +251-926434658 Received: 12 November 2020; Accepted: 11 December 2020; Published: 15 December 2020 Abstract: Renewable energy sources (RESs) such as wind and solar are frequently hit by fluctuations due to, for example, insufficient wind or sunshine. Energy storage technologies (ESTs) mitigate the problem by storing excess energy generated and then making it accessible on demand. While there are various EST studies, the literature remains isolated and dated. The comparison of the characteristics of ESTs and their potential applications is also short. This paper fills this gap. Using selected criteria, it identifies key ESTs and provides an updated review of the literature on ESTs and their application potential to the renewable energy sector. The critical review shows a high potential application for Li-ion batteries and most fit to mitigate the fluctuation of RESs in utility grid integration sector. -

Fuel Properties Comparison

Alternative Fuels Data Center Fuel Properties Comparison Compressed Liquefied Low Sulfur Gasoline/E10 Biodiesel Propane (LPG) Natural Gas Natural Gas Ethanol/E100 Methanol Hydrogen Electricity Diesel (CNG) (LNG) Chemical C4 to C12 and C8 to C25 Methyl esters of C3H8 (majority) CH4 (majority), CH4 same as CNG CH3CH2OH CH3OH H2 N/A Structure [1] Ethanol ≤ to C12 to C22 fatty acids and C4H10 C2H6 and inert with inert gasses 10% (minority) gases <0.5% (a) Fuel Material Crude Oil Crude Oil Fats and oils from A by-product of Underground Underground Corn, grains, or Natural gas, coal, Natural gas, Natural gas, coal, (feedstocks) sources such as petroleum reserves and reserves and agricultural waste or woody biomass methanol, and nuclear, wind, soybeans, waste refining or renewable renewable (cellulose) electrolysis of hydro, solar, and cooking oil, animal natural gas biogas biogas water small percentages fats, and rapeseed processing of geothermal and biomass Gasoline or 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 1.12 B100 1 gal = 0.74 GGE 1 lb. = 0.18 GGE 1 lb. = 0.19 GGE 1 gal = 0.67 GGE 1 gal = 0.50 GGE 1 lb. = 0.45 1 kWh = 0.030 Diesel Gallon GGE GGE 1 gal = 1.05 GGE 1 gal = 0.66 DGE 1 lb. = 0.16 DGE 1 lb. = 0.17 DGE 1 gal = 0.59 DGE 1 gal = 0.45 DGE GGE GGE Equivalent 1 gal = 0.88 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 0.93 DGE 1 lb. = 0.40 1 kWh = 0.027 (GGE or DGE) DGE DGE B20 DGE DGE 1 gal = 1.11 GGE 1 kg = 1 GGE 1 gal = 0.99 DGE 1 kg = 0.9 DGE Energy 1 gallon of 1 gallon of 1 gallon of B100 1 gallon of 5.66 lb., or 5.37 lb. -

Specific Energy Limit and Its Influence on the Nature of Black Holes Javier Viaña

Specific Energy Limit and its Influence on the Nature of Black Holes Javier Viaña To cite this version: Javier Viaña. Specific Energy Limit and its Influence on the Nature of Black Holes. 2021. hal- 03322333 HAL Id: hal-03322333 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03322333 Preprint submitted on 19 Aug 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 16th of August of 2021 Specific Energy Limit and its Influence on the Nature of Black Holes Javier Viaña [0000-0002-0563-784X] University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati OH 45219, USA [email protected] What if the universe has a limit on the amount of energy that a certain mass can have? This article explores this possibility and suggests a theory for the creation and nature of black holes based on an energetic limit. The Specific Energy Limit Energy is an extensive property, and we know that as we add more mass to a given system, we can easily increase its energy. Specific energy on the other hand is an intensive property. It is defined as the energy divided by the mass and it is measured in units of J/kg. -

Re-Examining the Role of Nuclear Fusion in a Renewables-Based Energy Mix

Re-examining the Role of Nuclear Fusion in a Renewables-Based Energy Mix T. E. G. Nicholasa,∗, T. P. Davisb, F. Federicia, J. E. Lelandc, B. S. Patela, C. Vincentd, S. H. Warda a York Plasma Institute, Department of Physics, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK b Department of Materials, University of Oxford, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PH c Department of Electrical Engineering and Electronics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 3GJ, UK d Centre for Advanced Instrumentation, Department of Physics, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LS, UK Abstract Fusion energy is often regarded as a long-term solution to the world's energy needs. However, even after solving the critical research challenges, engineer- ing and materials science will still impose significant constraints on the char- acteristics of a fusion power plant. Meanwhile, the global energy grid must transition to low-carbon sources by 2050 to prevent the worst effects of climate change. We review three factors affecting fusion's future trajectory: (1) the sig- nificant drop in the price of renewable energy, (2) the intermittency of renewable sources and implications for future energy grids, and (3) the recent proposition of intermediate-level nuclear waste as a product of fusion. Within the scenario assumed by our premises, we find that while there remains a clear motivation to develop fusion power plants, this motivation is likely weakened by the time they become available. We also conclude that most current fusion reactor designs do not take these factors into account and, to increase market penetration, fu- sion research should consider relaxed nuclear waste design criteria, raw material availability constraints and load-following designs with pulsed operation. -

Energy and the Hydrogen Economy

Energy and the Hydrogen Economy Ulf Bossel Fuel Cell Consultant Morgenacherstrasse 2F CH-5452 Oberrohrdorf / Switzerland +41-56-496-7292 and Baldur Eliasson ABB Switzerland Ltd. Corporate Research CH-5405 Baden-Dättwil / Switzerland Abstract Between production and use any commercial product is subject to the following processes: packaging, transportation, storage and transfer. The same is true for hydrogen in a “Hydrogen Economy”. Hydrogen has to be packaged by compression or liquefaction, it has to be transported by surface vehicles or pipelines, it has to be stored and transferred. Generated by electrolysis or chemistry, the fuel gas has to go through theses market procedures before it can be used by the customer, even if it is produced locally at filling stations. As there are no environmental or energetic advantages in producing hydrogen from natural gas or other hydrocarbons, we do not consider this option, although hydrogen can be chemically synthesized at relative low cost. In the past, hydrogen production and hydrogen use have been addressed by many, assuming that hydrogen gas is just another gaseous energy carrier and that it can be handled much like natural gas in today’s energy economy. With this study we present an analysis of the energy required to operate a pure hydrogen economy. High-grade electricity from renewable or nuclear sources is needed not only to generate hydrogen, but also for all other essential steps of a hydrogen economy. But because of the molecular structure of hydrogen, a hydrogen infrastructure is much more energy-intensive than a natural gas economy. In this study, the energy consumed by each stage is related to the energy content (higher heating value HHV) of the delivered hydrogen itself. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Ces-Collins-Pp-Ev-Conundrum

Gabriel Collins, J.D. Baker Botts Fellow for Energy & Environmental Regulatory Affairs Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University EVs = Power-to-WeigHt Ratio of an Aircraft, Onboard Fuel of a Subcompact Car • Electric veHicles’ instant torque and higH horsepower make the higher-end editions true performance monsters. Their power-to-weigHt ratios are often on par witH turboprop aircraft and many helicopters. • The fly in the ointment comes from the fact that batteries remain heavy and relative to hydrocarbons and simply cannot store energy nearly as efficiently per unit of mass. • The power-to-weigHt/onboard energy density relationsHip of the Rivian R1T electric truck and A-29 Big, long-range Super Tucano attack aircraft is sucH that platforms “Rivianizing” the Tucano would mean making its onboard jet fuel stores retain their current energy Super Tucano (17) and Rivian R1T (14) content, but weigH more per liter than lead metal. Needless to say, the plane’s fligHt endurance and carrying capacity would fall dramatically. • This estimate assumes the A-29’s PT-6 turboprop has a thermal efficiency of about 35%--less than half the R1T’s likely capacity to convert fuel into actual propulsive energy. Please cite as: Gabriel Collins, “The EV Conundrum: High Power Density and Low Energy Density,” Baker Institute ResearcH Source: Beechcraft, Car & Driver, EIA, EV Database, GE, Global Security, Man, Nikola, Peterbuilt, Rivian, SNC, Trucks.com, USAF, US Navy Presentation, 8 January 2020, Houston, TX Gabriel Collins, J.D. Baker Botts Fellow for Energy & Environmental Regulatory Affairs Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University Electric Vehicles’ Onboard Energy Still Significantly Trails ICE Vehicles On an Efficiency-Adjusted Basis Efficiency-Adjusted Comparison • To make the energy density comparison a bit more fair, we adjust the onboard fuel based on the fact that EVs convert nearly 80% of their battery energy into tractive power at the wheels, while IC vehicles feature efficiencies closer to 20%. -

Sodium‐Ion Batteries Paving the Way for Grid Energy Storage

ESSAY 10th Anniversary Article www.advenergymat.de Sodium-Ion Batteries Paving the Way for Grid Energy Storage Hayley S. Hirsh, Yixuan Li, Darren H. S. Tan, Minghao Zhang, Enyue Zhao, and Y. Shirley Meng* Dedicated to the pioneering scientists whose work have made sodium-ion batteries possible bridge the disconnect between renewables The recent proliferation of renewable energy generation offers mankind hope, generation and distribution for consump- with regard to combatting global climate change. However, reaping the full tion. While stationary storage such as benefits of these renewable energy sources requires the ability to store and pumped hydroelectric and compressed air exist, their lack of flexible form factors and distribute any renewable energy generated in a cost-effective, safe, and sus- lower energy efficiencies limit their scal- tainable manner. As such, sodium-ion batteries (NIBs) have been touted as able adoption for urban communities.[2] an attractive storage technology due to their elemental abundance, promising Thus, batteries are believed to be more electrochemical performance and environmentally benign nature. Moreover, practical for large-scale energy storage new developments in sodium battery materials have enabled the adoption of capable of deployment in homes, cities, high-voltage and high-capacity cathodes free of rare earth elements such as Li, and locations far from the grid where the traditional electrical infrastructure does Co, Ni, offering pathways for low-cost NIBs that match their lithium coun- not reach. terparts in energy density while serving the needs for large-scale grid energy Today’s battery technologies are domi- storage. In this essay, a range of battery chemistries are discussed alongside nated by lithium ion batteries (LIBs) and their respective battery properties while keeping metrics for grid storage in lead acid batteries. -

Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage and Superconducting Self-Supplied Electromagnetic Launcher★

Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 80, 20901 (2017) THE EUROPEAN © EDP Sciences, 2017 PHYSICAL JOURNAL DOI: 10.1051/epjap/2017160452 APPLIED PHYSICS Regular Article Superconducting magnetic energy storage and superconducting self-supplied electromagnetic launcher★ Jérémie Ciceron*, Arnaud Badel, and Pascal Tixador Institut Néel, G2ELab CNRS/Université Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France Received: 5 December 2016 / Received in final form: 8 April 2017 / Accepted: 16 August 2017 Abstract. Superconductors can be used to build energy storage systems called Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES), which are promising as inductive pulse power source and suitable for powering electromagnetic launchers. The second generation of high critical temperature superconductors is called coated conductors or REBCO (Rare Earth Barium Copper Oxide) tapes. Their current carrying capability in high magnetic field and their thermal stability are expanding the SMES application field. The BOSSE (Bobine Supraconductrice pour le Stockage d’Energie) project aims to develop and to master the use of these superconducting tapes through two prototypes. The first one is a SMES with high energy density. Thanks to the performances of REBCO tapes, the volume energy and specific energy of existing SMES systems can be surpassed. A study has been undertaken to make the best use of the REBCO tapes and to determine the most adapted topology in order to reach our objective, which is to beat the world record of mass energy density for a superconducting coil. This objective is conflicting with the classical strategies of superconducting coil protection. A different protection approach is proposed. The second prototype of the BOSSE project is a small-scale demonstrator of a Superconducting Self-Supplied Electromagnetic Launcher (S3EL), in which a SMES is integrated around the launcher which benefits from the generated magnetic field to increase the thrust applied to the projectile. -

Specific Energy

Quantum Mechanics_Specific energy Specific energy SI unit J/kg In SI base units m2/s2 Derivations from other quantities e = E/m Energy density has tables of specific energies of devices and materials. Specific energy is energy per unit mass. (It is also sometimes called "energy density," though "energy density" more precisely means energy per unit volume.) It is used to quantify, for example, stored heat or other thermodynamic propertiesof substances such as specific internal energy, specific enthalpy, specific Gibbs free energy, and specific Helmholtz free energy. It may also be used for the kinetic energy or potential energy of a body. Specific energy is an intensive property, whereas energy and mass are extensive properties. The SI unit for specific energy is the joule per kilogram (J/kg). Other units still in use in some contexts are the kilocalorie per gram (Cal/g or kcal/g), mostly in food-related topics, watt hours per kilogram in the field of batteries, and theImperial unit BTU per pound (BTU/lb), in some engineering and applied technical fields.[1] The gray and sievert are specialized measures for specific energy absorbed by body tissues in the form of radiation. The following table shows the factors for converting to J/kg: Unit SI equivalent kcal/g[2] 4.184 MJ/kg Wh/kg 3.6 kJ/kg kWh/kg 3.6 MJ/kg Btu/lb[3] 2.326 kJ/kg Btu/lb[4] ca. 2.32444 kJ/kg The concept of specific energy is related to but distinct from the chemical notion of molar energy, that is energy per mole of a substance. -

The International System of Units (SI)

NAT'L INST. OF STAND & TECH NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology Technology Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce NIST Special Publication 330 2001 Edition The International System of Units (SI) 4. Barry N. Taylor, Editor r A o o L57 330 2oOI rhe National Institute of Standards and Technology was established in 1988 by Congress to "assist industry in the development of technology . needed to improve product quality, to modernize manufacturing processes, to ensure product reliability . and to facilitate rapid commercialization ... of products based on new scientific discoveries." NIST, originally founded as the National Bureau of Standards in 1901, works to strengthen U.S. industry's competitiveness; advance science and engineering; and improve public health, safety, and the environment. One of the agency's basic functions is to develop, maintain, and retain custody of the national standards of measurement, and provide the means and methods for comparing standards used in science, engineering, manufacturing, commerce, industry, and education with the standards adopted or recognized by the Federal Government. As an agency of the U.S. Commerce Department's Technology Administration, NIST conducts basic and applied research in the physical sciences and engineering, and develops measurement techniques, test methods, standards, and related services. The Institute does generic and precompetitive work on new and advanced technologies. NIST's research facilities are located at Gaithersburg, MD 20899, and at Boulder, CO 80303. -

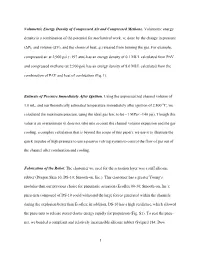

1 Volumetric Energy Density of Compressed Air and Compressed

Volumetric Energy Density of Compressed Air and Compressed Methane. Volumetric energy density is a combination of the potential for mechanical work, w, done by the change in pressure (P), and volume (V), and the chemical heat, q, released from burning the gas. For example, compressed air at 2,900 psi (~197 atm) has an energy density of 0.1 MJ/L calculated from PV and compressed methane (at 2,900 psi) has an energy density of 8.0 MJ/L calculated from the combination of PV and heat of combustion (Eq. 1). Estimate of Pressure Immediately After Ignition. Using the unpressurized channel volume of 1.0 mL, and our theoretically estimated temperature immediately after ignition of 2,800 oC, we calculated the maximum pressure, using the ideal gas law, to be ~1 MPa (~140 psi). Though this value is an overestimate (it does not take into account the channel volume expansion and the gas cooling, a complex calculation that is beyond the scope of this paper), we use it to illustrate the quick impulse of high pressure to use a passive valving system to control the flow of gas out of the channel after combustion and cooling. Fabrication of the Robot. The elastomer we used for the actuation layer was a stiff silicone rubber (Dragon Skin 10, DS-10; Smooth-on, Inc.). This elastomer has a greater Young’s modulus than our previous choice for pneumatic actuation (Ecoflex 00-30; Smooth-on, Inc.); pneu-nets composed of DS-10 could withstand the large forces generated within the channels during the explosion better than Ecoflex; in addition, DS-10 has a high resilience, which allowed the pneu-nets to release stored elastic energy rapidly for propulsion (Fig.