Japanese Maple Scale in the Nursery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US EPA, Pesticide Product Label, SVP8, 12/17/2010

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20460 OFFICE OF CHEMICAL SAFETY AND POLLUTION PREVENTION Joseph A. Conti Summit VetPharm 301 Route 17 North Rutherford, New Jersey 07070 DEC 1 7 Subject: Notification: Alternate Brand Names SVP8 EPA Reg. No. 83399-9 Date Submitted: December 1, 2010 Alternate Brand Names: SimpleGuard for Cats SimpleGuard for Cats and Kittens Dear Mr. Conti: The Agency is in receipt of your Application for Pesticide Notification under Pesticide Registration Notice (PRN) 98-10 dated December 1, 2010 for the product referenced above. The Registration Division (RD) has conducted a review of this request for its applicability under PRN 98-10 and finds that the action requested falls within the scope of PRN 98-10. The label submitted with the application has been stamped "Notification" and will be placed in our records. If you have any questions, please contact me at (703) 306-0415 or [email protected]. Sincerely, Kable Bo Davis Entomologist Insecticide-Rodenticide Branch Office of Pesticide Programs Print Form ^S£je_ntd_[ngtn/ctipru on revent form. Form Approved. OMB No. 2070-O060 United Statoe Registration OPP Identifier Number v>EPA ntal Protection Agency X Amendment 'oflliinoton, DC 20460 X Other Application for Pesticide - Section 1. Company/Product Number 2. EPA Product Manager 3. Proposed Classification 83399-9 J. Hebert 1 Restricted 4. Company/Product (Name) PM* SVP8 7 5. Name and Addroos of Applicant (Include ZIP Code) 6. Expedited Review. In accordance with FIFRA Section 3(c)(3) SummitVetPharm (b)(i), my product Is similar or identical In composition and labeling 301 Route 17 North to: Rutherford, New Jersey 07070 EPA Reg. -

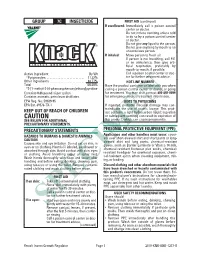

Insect Growth Regulator KEEP out of REACH of CHILDREN. CAUTION

SPECIMEN LABEL Archer® 1 PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS Hazards to Humans and Domestic Animals CAUTION Harmful if swallowed or absorbed through skin. Do not breathe vapor or spray mist. Avoid contact with skin or eyes. In case of contact, flush with plenty of water. Wash with soap and warm water after use. Obtain medical attention if irritation persists. Avoid contamination of food or feedstuffs. Environmental Hazards This product is toxic to fish and aquatic invertebrates. Do not apply directly to bodies of water, or to areas where surface water is present, or to intertidal areas below the mean high water mark. Do not contaminate water when cleaning equipment or disposing Insect Growth Regulator of equipment wash water. An insect growth regulator (IGR) for use in homes, apartments, Physical or Chemical Hazards schools, warehouses, offices, and other private, commercial or Do not use or store near heat or open flame. public buildings, in non-food preparation areas of food handling and processing establishments, in transport vehicles, animal CONDITIONS OF SALE AND LIMITATION OF housing facilities, and outdoor perimeter treatments on and adjacent to buildings and structures, and in pet areas WARRANTY AND LIABILITY A c t i v e I ngr edien t : NOTICE: Read the entire Directions for Use and Conditions 2- [ 1- m et hy l- 2- ( 4- p he no x y 1 phen.... ox1 .3y% ) et hoxof Sale y ] and py Limitation r i dine of Warranty and Liability before buying Other Ingredients* 98.7% or using this product. If the terms are not acceptable, return the product at once, unopened, and the purchase price will be Tot al: 100. -

Cockroach Control Manual

COCKROACHCOCKROACH CONTROLCONTROL MANUALMANUAL (Photo by J. Kalisch) Barb Ogg, Extension Educator, Lancaster County Clyde Ogg, Extension Educator, Pesticide Safety Education Program Dennis Ferraro, Extension Educator, Douglas & Sarpy Counties Extension is a Division of the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln cooperating with the Counties and the United States Department of Agriculture. ® University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension’s educational programs abide with the nondiscrimination policies of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and the United States Department of Agriculture. Table of Contents 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 5 Chapter 2: Know Your Enemy 9 Chapter 3: Cockroach Biology 15 Chapter 4: Locate Problem Areas 23 Chapter 5: Primary Control Strategies: Modify Resources 31 Chapter 6: Low-Risk Control Strategies 37 Chapter 7: Insecticide Basics 45 Chapter 8: Insecticides and Your Health 53 Chapter 9: Insecticide Applications 59 Chapter 10: Putting a Management Plan Together i Cockroach Control Manual Preface It has been more than 10 years since the first edition of the Cockroach Control Manual was completed. While the basic steps for effective and safe cockroach control are still the same, there are more types of control products available than there were 10 years ago. This means you have even more choices in your arsenal to help fight roaches. The Cockroach Control Manual is a practical reference for persons who have had little or no training in insect identification, biology or control methods. We know most people want low toxic methods used inside their homes so we are emphasizing low-risk strategies even more than in the original edition. -

Insecticide and Growth Regulator Effects on the Leafminer, Liriomyza Trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae), in Celery and Observations on Parasitism

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 21 Number 2 - Summer 1988 Number 2 - Summer Article 1 1988 June 1988 Insecticide and Growth Regulator Effects on the Leafminer, Liriomyza Trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae), in Celery and Observations on Parasitism E. Grafius Michigan State University J. Hayden Michigan State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Grafius, E. and Hayden, J. 1988. "Insecticide and Growth Regulator Effects on the Leafminer, Liriomyza Trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae), in Celery and Observations on Parasitism," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 21 (2) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol21/iss2/1 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Grafius and Hayden: Insecticide and Growth Regulator Effects on the Leafminer, <i>Lir 1988 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 49 INSECTICIDE AND GROWTH REGULATOR EFFECTS ON THE LEAFMINER, LIRIOMYZA TRIFOLII (DIPTERA: AGROMYZIDAE), IN CELERY AND OBSERVATIONS ON PARASITISM E. Grafius and 1. Haydenl ABSTRACT The effects of different insecticides were compared on survival and development of the leafminer, L. trifolii, in celery in Michigan and parasitism was assessed in this non resident population. Avermectin, thiocyclam, and cyromazine effectively controlled L. trifolii larvae or prevented successful emergence as adults. Moderate to high levels of resistance to permethrin and chlorpyrifos were present. Avermectin caused high mortality of all larval stages and no adults successfully emerged. -

Effect of Insect Growth Regulators on Citrus Mealybug

HORTSCIENCE 38(7):1397–1399. 2003. a result of insecticide applications is referred to as “hormoligosis” (Luckey, 1968). Hor- moligosis has been implicated in the increase Effect of Insect Growth Regulators on of female fecundity in several insect species such as Scirtothrips citri(Moulton) (Morse and Citrus Mealybug [Planococcus citri Zareh, 1991), Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Lale 1991), Zabrotes subfasciatus(Boheman), (Homoptera: Pseudococcidae)] Egg andAcanthoscelides obtectus(Say) (Weaver et al., 1992). Low doses of conventional insecti- cides have been implicated in increasing the Production fecundity of certain pests, including Coccus Raymond A. Cloyd hesperidum (L.) (Hart et al., 1966). In addi- tion to increasing egg production, insecticides University of Illinois, Department of Natural Resources and Environmental may also alter insect sex ratios (Dittrich et Sciences, 384 National Soybean Research Laboratory, 1101 West Peabody al., 1974). Drive, Urbana, IL 61801 Some insect growth regulators that act as juvenile hormone mimics reduce reproduction Additional index words. coleus, insect growth regulators, kinoprene, pyriproxyfen, by sterilizing females (Hamlen, 1977). In fact, buprofezin, novaluron, azadirachtin, interiorscapes, mealybugs insect growth regulators have been shown to Abstract. Greenhouse trials were conducted in 2000–2001 to evaluate the indirect effects of drastically reduce the fecundity of beneficial insects such as the ladybird beetles, Adalia insect growth regulators, whether stimulatory or inhibitory, on the egg production of female bipunctata Coccinella septempunctata citrus mealybug [Planococcus citri(Risso)]. Green coleus [Solenostemon scutellarioides (L.) L. and Codd] were infested with 10 late third instar female citrus mealybugs. The insect growth L. (Olszak et al., 1994). Regardless, there is still regulators kinoprene, pyriproxyfen, azadirachtin, buprofezin, and novaluron were applied minimal information on the potential indirect to infested plants at both the high and low manufacturer recommended rates. -

This Is a Specimen Label and May Be Inaccurate Or out of Date. It Is Intended As a Guide in Providing General Information Regarding Use of This Product

This is a specimen label and may be inaccurate or out of date. It is intended as a guide in providing general information regarding use of this product. Always read and follow the EPA approved label on the product container. PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL HAZARDS Do not use or store near heat or open flame. CONDITIONS OF SALE AND LIMITATION OF WARRANTY AND LIABILITY NOTICE: Read the entire Directions for Use and Conditions of Sale and An insect growth regulator (IGR) for use in homes, apartments, schools, Limitation of Warranty and Liability before buying or using this product. If warehouses, offices, and other private, commercial, or public buildings, in the terms are not acceptable, return the product at once, unopened, and nonfood preparation areas of food handling and processing establishments, the purchase price will be refunded. in transport vehicles, animal housing facilities, and barrier treatments on and The Directions for Use of this product should be followed carefully. It is adjacent to buildings and structures and in pet areas. impossible to eliminate all risks inherently associated with the use of this ACTIVE INGREDIENT product. Ineffectiveness or other unintended consequences may result 2-[1-Methyl-2-(4-phenoxyphenoxy) ethoxy] pyridine . .1.3% because of such factors as manner of use or application, weather, INERT INGREDIENTS* . .98.7% presence of other materials or other influencing factors in the use of the product, which are beyond the control of ZENECA or Seller. All such risks TOTAL . 100.0% shall be assumed by Buyer and User, and Buyer and User agree to hold *Contains petroleum distillates ZENECA and Seller harmless for any claims relating to such factors. -

How Insecticides Work

Bringing information and education into the communities of the Granite State How Insecticides Work Dr. Alan T. Eaton, Extension Specialist, Entomology The variety of insecticides available today is much greater than it was 20 years ago. It includes some made from bacteria, insect- killing fungi or viruses; products such as insecticidal soaps that kill by physical processes; and products like the clay-based Surround that don’t directly kill insects, but protect plants. Most of the insecticides in common use today are toxic to people as well as well as insects, although the degree of toxicity to people depends on the dose of the material and the mechanism of action, among other factors. Some toxicants affect the nervous system. Others affect water balance, oxygen metabolism, an insect’s molting or maturation process, or other aspects of physiology. Some of the newer insecticides have toxicity mechanisms that scientists don’t fully understand. New materials are being synthesized and tested constantly. Some pesticides (even organic ones) can cause burn of plant tissues if not applied carefully. Many common insecticides in general use fit into the following Photo: Alan T. Eaton. classes: Organophosphates (OP) Chlorpyrifos and malathion are organophosphates. They interfere with the transmission of nerve impulses. Their point of action is the synapse, the tiny gap between one nerve fiber and the next. Nerve impulses jump such gaps with the aid of chemicals called neurotransmitters. Enzymes normally destroy these chemicals immediately after the nerve impulse crosses the gap. Among the most common neurotransmitters is acetylcholine, which functions in our bodies the same way as it does in insects. -

2019-Knk-0001-1277-R

GROUP 7C INSECTICIDE FIRST AID (continued) If swallowed: Immediately call a poison control center or doctor. Do not induce vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. Do not give any liquid to the person. Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. If inhaled: Move person to fresh air. If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambulance, then give arti- ficial respiration, preferably by mouth-to-mouth, if possible. Active Ingredient By Wt Call a poison control center or doc- *Pyriproxyfen ��������������������������������������������������� 11.23% tor for further treatment advice. Other Ingredients . 88.77% HOT LINE NUMBER Total 100.00% Have the product container or label with you when *2-[1-methyl-2-(4-phenoxyphenoxy)ethoxy]pyridine calling a poison control center or doctor, or going Contains 0.86 pound ai per gallon. for treatment. You may also contact 800-892-0099 Contains aromatic petroleum distillates. for emergency medical treatment information. EPA Reg. No. 59639-95 NOTE TO PHYSICIANS EPA Est. 39578-TX-1 If ingested, probable mucosal damage may con- traindicate the use of gastric lavage. This prod- KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN uct contains a light hydrocarbon liquid; ingestion CAUTION or subsequent vomiting can result in aspiration of SEE BELOW FOR ADDITIONAL this product, which can cause pneumonitis. PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS. PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE): HAZARDS TO HUMANS & DOMESTIC ANIMALS Applicators and other handlers must wear: cover- CAUTION alls over short-sleeved shirt and short pants or long- sleeved shirt and long pants, chemical-resistant Causes skin and eye irritation. -

Bed Bug Treatment Using Insecticides Dini M

Bed Bug Treatment Using Insecticides Dini M. Miller, Ph.D., Department of Entomology, Virginia Tech Introduction The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is responsible for protecting people from exposure to pesticides. To do this, they have very strict toxicity testing methods that chemical manufacturers must use to determine how harmful exposure to these pesticides may be to mammals (people, dogs and cats) or the environment. The test results are carefully reviewed by the EPA before a pesticide product is allowed to be sold in the United States. If a pesticide is found to be either too toxic or it lasts too long in the environment it will never be registered for use. However, those pesticides that are not long-term envi- ronmental contaminates and that have very low mammalian toxicity will be allowed to be used, under strict conditions. For instance, those pesticides that do not produce harmful effects (either acute or long-term effects) at a particular dose, will still be required to have a 100-1000-fold margin of safety before they can be used in the human environment. In other words, a product dose may be reduced 100-1000 times before it can be registered (See the Food Quality pro- tection Act for more information). As you can imagine, some pesticides may no longer kill pests at such a low dose, and never come to market. The use of those products that pass the toxicity testing and margin of safety is still restricted by the pesticide label. The pesticide label is a legal document that is attached to every pesticide. -

Proposed Structural Special Use Products

Proposed Pesticide Product List Proposed Structural Allowed Products Applied and monitored by licensed professional applicators Groundwater Active Ingredient Material Signal Word EPA Reg # Use Prop 65 EPA Carcinogenicity Criteria for Use & Limitations List 2-phenethyl propionate, SF, insecticide-crawling ECO PCO ACU Caution 67425-14-AA No No Not Listed Structural insects OW insects EVAC is an EPA reduced risk biologically based pesticide' it’s not Balsam Fir Oil. Other EVAC Botanical botanical rodent OMRI listed and it's not listed as organic. This product may have ingredients: Fragrance oil, N/A 82016-1-64405 No No Not Listed rodent repellant repellant limited use and a low percentage of success, but it is one of the few plant fibers alternative controls available to reduce rodent damage N/A. U .S. Eugenol (Clove Insects, ants, roaches, Granular material to be used for sow bug infestations under moist EcoEXEMPT G Caution Patent No. No Not Listed Not Listed EU List Oil), Thyme Oil sowbugs/pillbugs conditions. 6,004,569 phenethyl propionate, insecticide-crawling EcoExempt D Caution N/A No No Not Listed Structural insects, exterior, clove oil - Organic eugenol, SF, EW, OW insects Rosemary Oil, Insecticide-crawling Contains petroleum distillates. Replaces EcoExempt IC2 PAN Geraniol, Essentria IC3 Caution N/A No No Not Listed EU List and flying insects gives all the active ingredients in this product a good review. Peppermint Oil Applied and monitored by licensed professional applicators Proposed Structural Special Use Products Groundwater Active Ingredient Material Signal Word EPA Reg # Use Prop 65 EPA Carcinogenicity Criteria for Use & Limitations List Evidence of ants, roaches, pillbugs, Non- Boric Acid Perma-Dust Caution 499-384 No Not Listed EU List Perma Dust replaces Turbo Dust. -

Cockroaches and Their Management1 P

ENY-214 Cockroaches and Their Management1 P. G. Koehler, B. E. Bayer, and D. Branscome2 or dying plants and animals. However, they are considered pests when they interact with people, invading lawns and gardens or entering homes and other structures. More importantly, they can affect human health by spreading diseases, such as Salmonella, and ruin materials such as books, clothes and food. Cockroaches secrete an oily liquid that has an offensive and sickening odor. This odor may also be imparted to dishes that are apparently clean, food and clothes. Excrement in the form of pellets or an inklike liquid also contributes to this nauseating odor. Additionally, cockroaches produce allergens, which include their feces, shed skins, and body parts such as antennae and legs. In susceptible individuals, contact with these allergens can result in mild to severe rashes, other allergic reactions, and in extreme cases death from asthma attacks. Cockroach Species This fact sheet is excerpted from SP486: Pests in and around the Southern Home, which is available from the UF/IFAS Extension The cockroaches most commonly found in and around Bookstore. http://ifasbooks.ifas.ufl.edu/p-1222-pests-in-and-around- Florida homes are the Florida woods roach (Figure 1), the-southern-home.aspx American (Figure 2), smokybrown (Figure 3), brown (Figure 4), Australian (Figure 5), German (Figure 6) and Cockroaches have various common names including water Asian (Figure 7). The smallest cockroaches—the German, bugs, croton bugs and palmetto bugs. There are at least Asian and brownbanded (Figure 8)—are close to the same 69 different cockroach species found in the United States. -

Laboratory and Field Effects of the Insect Growth Regulator Diflubenzuron on the European Corn Borer Abdel Rahman Abdel Fattah Faragalla Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1979 Laboratory and field effects of the insect growth regulator diflubenzuron on the European corn borer Abdel Rahman Abdel Fattah Faragalla Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Faragalla, Abdel Rahman Abdel Fattah, "Laboratory and field effects of the insect growth regulator diflubenzuron on the European corn borer " (1979). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7207. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7207 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity.