(Tourism) Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Study North Field Historic District

Tinian National Historical ParkStudy Page 1 of 26 SPECIAL STUDY NORTH FIELD HISTORIC DISTRICT Tinian Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands September 2001 United States Department of the Interior - National Park Service http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/Tinian/tiniandr.htm 4/9/2008 Tinian National Historical ParkStudy Page 2 of 26 http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/Tinian/tiniandr.htm 4/9/2008 Tinian National Historical ParkStudy Page 3 of 26 North Field as it looked during World War II. The photo shows only three runways, which dates it sometime earlier than May 1945 when construction of Runway Four was completed. North Field was designed for an entire wing of B-29 Superfortresses, the 313th Bombardment Wing, with hardstands to park 265 B-29s. Each of the parallel runways stretched more than a mile and a half in length. Around and between the runways were nearly eleven miles of taxiways. Table of Contents SUMMARY BACKGROUND DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA Location, Size and Ownership Regional Context RESOURCE SIGNIFICANCE Current Status of the Study Area Cultural Resources Natural Resources Evaluation of Significance EVALUATION OF SUITABILITY AND FEASIBILITY Rarity of This Type of Resource (Suitability) Feasibility for Protection Position of CNMI and Local Government Officials http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/Tinian/tiniandr.htm 4/9/2008 Tinian National Historical ParkStudy Page 4 of 26 Plans and Objectives of the Lease Holder FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Findings and Conclusions Recommendations APPENDIX Selected References CINCPACFLT Letter of July 26, 2000 COMNAVMAR Letter of August 28, 2001 Brochure: Self-Guided Tour of North Field Tinian Interpret Marianas Campaign from American Memorial Park, on Tinian, and with NPS Publications MAPS Figure 1. -

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

Form No. 10-300 Ul^l mu^l Alta ucr/VKl ivicix i wr i nc, UN i E.IMWIV NATIONAL PARK SERVICE '•SS'^:?!®.^ s$lliil®'^^^:'s^ :^:'!i^'-'-^'®'':^:^w^ NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES 1 ^^i^isiii^^|:^^i^§iilP:S-illi Hill INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM 1 iiPiiPii^i^iiii xisJiSSg:; SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Suicide Cliff ANO/OR COMMON .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Saipan,/1^7 OF STATE Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands 969^8UNTY CODE CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE D I STRICT —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM BUILDING!S) PRIVATE ^.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL JXPARK STRUCTURE BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC BEING CONSIDERED —*YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY _OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands STREET & NUMBER Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands - Headquarters CITY, TOWN STATE TTPI 96950 VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Attorney General, Office of the High Commissioner STREET & NUMBER Saipan Island CITY, TOWN STATE Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands 96950 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Micronesian Parks, DATE July, 1972 XL-FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS U.S Department of the Interior, Hawaii Group, National Park Service CITY. TOWN STATE 667 Ala Moana Boulevard, suite 512, Honolulu, Hawaii 96950 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Suicide Cliff is a section of the Banadero cliff line. -

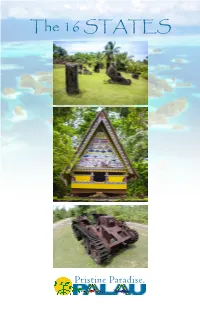

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS OPERATIONAL LOGISTICS CONTINGENCY PLAN PART 2 –EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITY & OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS SITUATION GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP FEBRUARY – MARCH 2011 1 | P a g e A. Summary A. SUMMARY 2 B. EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITIES 4 C. LOGISTICS ACTORS 6 A. THE LOGISTICS COORDINATION GROUP 6 B. PAPUA NEW GUINEAN ACTORS 6 AT NATIONAL LEVEL 6 AT PROVINCIAL LEVEL 9 C. INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION BODIES 10 DMT 10 THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 10 D. OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURE, SERVICES & STOCKS 11 A. LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURES OF PNG 11 PORTS 11 AIRPORTS 14 ROADS 15 WATERWAYS 17 STORAGE 18 MILLING CAPACITIES 19 B. LOGISTICS SERVICES OF PNG 20 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS 20 FUEL SUPPLY 20 TRANSPORTERS 21 HEAVY HANDLING AND POWER EQUIPMENT 21 POWER SUPPLY 21 TELECOMS 22 LOCAL SUPPLIES MARKETS 22 C. CUSTOMS CLEARANCE 23 IMPORT CLEARANCE PROCEDURES 23 TAX EXEMPTION PROCESS 24 THE IMPORTING PROCESS FOR EXEMPTIONS 25 D. REGULATORY DEPARTMENTS 26 CASA 26 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 26 NATIONAL INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY (NICTA) 27 2 | P a g e MARITIME AUTHORITIES 28 1. NATIONAL MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY 28 2. TECHNICAL DEPARTMENTS DEPENDING FROM THE NATIONAL PORT CORPORATION LTD 30 E. PNG GLOBAL LOGISTICS CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 34 A. CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 MAJOR PROBLEMS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: 34 SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 B. EXISTING OPERATIONAL CORRIDORS IN PNG 35 MAIN ENTRY POINTS: 35 SECONDARY ENTRY POINTS: 35 EXISTING CORRIDORS: 36 LOGISTICS HUBS: 39 C. STORAGE: 41 CURRENT SITUATION: 41 PROPOSED LONG TERM SOLUTION 41 DURING EMERGENCIES 41 D. DELIVERIES: 41 3 | P a g e B. Existing response capacities Here under is an updated list of the main response capacities currently present in the country. -

Nakatani V. Nishizono, 2 ROP Intrm. 7 (1990) NORIYOSHI NAKATANI and NAKATANI CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, Respondents

Nakatani v. Nishizono, 2 ROP Intrm. 7 (1990) NORIYOSHI NAKATANI and NAKATANI CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, Respondents, v. MASAO NISHIZONO and SEIBU DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, Appellants, and REPUBLIC OF PALAU, Additional Appellant, and PACIFICA DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, a Palau Corporation. MASAO NISHIZONO, aka KWON BOO SIK CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, Appellant, v. ROMAN TMETUCHL, MELWERT TMETUCHL, and NORIYOSHI NAKATANI, Respondents, and ⊥8 REPUBLIC OF PALAU, Additional Appellant, and PACIFICA DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION a Palau Corporation, Respondent. CIVIL APPEAL NO. 5-86 Civil Action No. 25-85 and Civil Action No. 73-85 (consolidated) Supreme Court, Appellate Division Republic of Palau Opinion Decided: January 8, 1990 Nakatani v. Nishizono, 2 ROP Intrm. 7 (1990) Counsel for Appellants Masao Nishizono and Seibu Development Corporation: James S. Brooks Counsel for Respondents Noriyoshi Nakatani and Nakatani Company: John S. Tarkong Counsel for Appellant Republic of Palau: Richard Brungard, Acting Attorney General. Counsel for Appellee Pacifica Development Corp. and Melwert Tmetuchl and Respondents Roman Tmetuchl and Airai State Gov’t.: Johnson Toribiong BEFORE: ALEX R. MUNSON,1 Associate Justice; ROBERT A. HEFNER,2 Associate Justice; FREDERICK J. O’BRIEN, Associate Justice Pro Tem. ⊥9 PER CURIAM: As will be seen, the issues presented for this appeal are limited in scope and therefore an extensive dissertation as to the factual and procedural history for this protracted litigation is unnecessary. Only the background necessary for the resolution of the issues raised for this appellate panel need be set forth in any detail. BACKGROUND Civil Action No. 73-85 was commenced on May 9, 1985, when plaintiffs Noriyoshi Nakatani and Nakatani Construction Co. (Nakatani) filed their complaint against Masao Nishizono, AKA Kwon Boo Sik (Nishizono), Seibu Development Corporation, Seibu Sohgo Kaihatsu, Hisayuki Kojima, Airai State, and Roman Tmetuchl, individually and as Governor of Airai State. -

In the Northern Mariana Islands

THE TRADITIONAL AND CEREMONIAL USE OF THE GREEN TURTLE (Chelonia mydas) IN THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS with recommendations for ITS USE IN CULTURAL EVENTS AND EDUCATION A Report prepared for the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council and the University of Hawaii Sea Grant College Program by Mike A. McCoy Kailua-Kona, Hawaii December, 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................4 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................8 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................9 1.1 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................9 1.2 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND METHODOLOGY ............................................................................10 1.3 DISCUSSION OF DEFINITIONS .........................................................................................................11 2. GREEN TURTLES, ISLANDS AND PEOPLE OF THE NORTHERN MARIANAS ...................12 2.1 SUMMARY OF GREEN TURTLE BIOLOGY.....................................................................................12 2.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS ............................................................14 2.3 SOME RELEVANT -

Republic of Palau Hearing Committee on Energy And

S. HRG. 112–121 REPUBLIC OF PALAU HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION TO REVIEW S. 343, A BILL TO AMEND TITLE I OF P.L. 99–658 REGARDING THE COMPACT OF FREE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE GOVERNMENT OF PALAU, TO APPROVE THE RESULTS OF THE 15-YEAR REVIEW OF THE COMPACT, INCLUDING THE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERN- MENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU FOLLOWING THE COMPACT OF FREE ASSOCIATION SECTION 432 REVIEW, TO APPROPRIATE FUNDS FOR THE PURPOSES OF THE AMENDED P.L. 99–658 FOR FISCAL YEARS ENDING ON OR BEFORE SEPTEMBER 30, 2024, AND TO CARRY OUT THE AGREEMENTS RESULTING FROM THAT REVIEW JUNE 16, 2011 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 70–661 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico, Chairman RON WYDEN, Oregon LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho MARIA CANTWELL, Washington MIKE LEE, Utah BERNARD SANDERS, Vermont RAND PAUL, Kentucky DEBBIE STABENOW, Michigan DANIEL COATS, Indiana MARK UDALL, Colorado ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JOHN HOEVEN, North Dakota AL FRANKEN, Minnesota DEAN HELLER, Nevada JOE MANCHIN, III, West Virginia BOB CORKER, Tennessee CHRISTOPHER A. -

The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future

OIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIA The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future The Republic of Palau is located roughly 500 miles east of the Philippines in the Western Pacific Ocean. The country consists of 189 square miles of land spread over more than 340 islands, only nine of which are inhabited: 95% of the land area lies within a single reef structure that includes the islands of Babeldaob (a.k.a. Babelthuap), Peleliu and Koror. Palau and the United States have a strong relationship as enshrined in the Compact of Free Association, U.S. Public Law 99-658. Palau has made a concerted effort in goals set forth in its energy policy. recent years to address the technical, The country completed its National policy, social and economic hurdles Climate Change Policy in 2015 and Energy & Climate Facts to deploying energy efficiency and made a commitment to reduce Total capacity (2015): 40.1 MW renewable energy technologies, and has national greenhouse gas emissions Diesel: 38.8 MW taken measures to mitigate and adapt to (GHGs) as part of the United Nations Solar PV: 1.3 MW climate change. This work is grounded in Framework Convention on Climate Total generation (2014): 78,133 MWh Palau’s 2010 National Energy Policy. Change (UNFCCC). Demand for electricity (2015): Palau has also developed an energy action However with a population of just Average/Peak: 8.9/13.5 MW plan to outline concrete steps the island over 21,000 and a gross national GHG emissions per capita: 13.56 tCO₂e nation could take to achieve the energy income per capita of only US$11,110 (2011) in 2014, Palau will need assistance Residential electric rate: $0.28/kWh 7°45|N (2013 average) Arekalong from the international community in REPUBLIC Peninsula order to fully implement its energy Population (2015): 21,265 OF PALAU and climate goals. -

America&Apos;S Unknown Avifauna: the Birds of the Mariana Islands

ß ß that time have been the basis for con- America's unknown avifauna. siderable concern (Vincent, 1967) and indeed appear to be the basis for the the birds of inclusion of several Mariana birds in the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (1976) list of the Mariana Islands Endangered Species.These brief war- time observationswere important, but no significant investigationshave been conductedin the ensuingthirty yearsto "Probably no otherAmerican birds determine the extent to which the are aspoorly known as these." endemic avifauna of these islands may haverecovered. Importantly, no assess- mentshave been made of the impactof H. Douglas Pratt, Phillip L. Bruner the military's aerial planting of the exoticscrubby tree known as tangan- and Delwyn G. Berrett tangan, Leucaenaglauca, to promote revegetationafter the war. This 'treeis known as "koa haole" in Hawaii. restricted both in their time for bird ß ß announcesthe signthat greets observation and in their movements on v•sitors to Guam. Few Americans realize the islands. Their studies were made in authorsURING THEvisitedSUMMER the islandsOF1076the of that the nation's westernmost territories 1945 and 1946 when most of the Mari- Saipan,Tinian, Rota, and Guam, and m he across the International Date Line in anaswere just beginningto recoverfrom 1978 Bruner and Pratt returned to Sai- the far westernPacific. Guam, the larg- the ravagesof war (Baker, 1946).Never- pan and Guam. We havespent a total of est and southernmost of the Mariana theless, population estimates made at 38 man/dayson Saipan,four on Tinian, Islands,has been a United Statesposses- s•on since Spain surrendered her sov- & Agrihan ereigntyover the island at the end of the Sparash-AmericanWar. -

Palau Along a Path of Sustainability, While Also Ensuring That No One Is Left Behind

0 FOREWORD I am pleased to present our first Voluntary National Review on the SDGs. This Review is yet another important benchmark in our ongoing commitment to transform Palau along a path of sustainability, while also ensuring that no one is left behind. This journey towards a sustainable future is not one for gov- ernment alone, nor a single nation, but for us all. Given the SDG’s inherent inter-linkages, we acknowledge that our challenges are also interrelated, and thus so too must be our solutions. The accelerated pace of global change we see today makes it particularly diffi- cult for small island nations, like Palau, to keep up, let alone achieve sustaina- ble development. Despite this challenge, we firmly believe that we can achieve a sustainable future for Palau. Our conviction stems from our certainty that we can confront our challenges by combining our lessons from the past with new information and modern technology and use them to guide us to stay the right course along our path to the future. Just as important, we are also confi- dent in this endeavor because we can also find solutions amongst each other. Over the past three years, Palau has systematically pursued a rigorous process of assessing our Pathways to 2030. Eight inter-sector working groups, led by government ministries, but including representatives from civil society, and semi-private organizations, have prepared this initial Voluntary National Review. The groups have selected an initial set of 95 SDG global targets and associated indicators that collectively constitute our initial National SDG Framework. -

Personnel - Johnston, Edward (2)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 39, folder “Personnel - Johnston, Edward (2)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 39 of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMIN I STRATION Presidential Libraries Withdrawal Sheet WITHDRAWAL ID 01510 REASON FOR WITHDRAWAL . Donor restriction TYPE OF MATERIAL Letter(s) CREATOR'S NAME . Thorpe, Richard RECEIVER'S NAME .... President DESCRIPTION . Trust Territory CREATION DATE 09/ 06/ 1974 COLLECTION/ SERIES/FOLDER ID 001900428 COLLECTION TITLE . Philip W. Buchen Files BOX NUMBER . 39 FOLDER TITLE . Personnel - Johnston, Edward ( 1)-(2) DATE WITHDRAWN . 08/ 26 / 1988 WITHDRAWING ARCHIVIST . LET NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION Presidential Libraries Withdrawal Sheet WITHDRAWAL ID 01511 REASON FOR WITHDRAWAL . Donor restriction TYPE OF MATERIAL Notes CREATOR'S NAME . Daughtrey, Eva DESCRIPTION Note for the file concerning Robert Thorpe phone calls . CREATION DATE . 06/24/1976 COLLECTION/SERIES/FOLDER ID .