Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome: in a Nutshell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 ILAE Classification & Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes in the Neonate

ILAE Classification & Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes in the Neonate and Infant: Position Statement by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions Authors: Sameer M Zuberi1, Elaine Wirrell2, Elissa Yozawitz3, Jo M Wilmshurst4, Nicola Specchio5, Kate Riney6, Ronit Pressler7, Stephane Auvin8, Pauline Samia9, Edouard Hirsch10, O Carter Snead11, Samuel Wiebe12, J Helen Cross13, Paolo Tinuper14,15, Ingrid E Scheffer16, Rima Nabbout17 1. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 4. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 5. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 6. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 7. Clinical Neuroscience, UCL- Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London, UK. Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE London, UK 8. Université de Paris, AP-HP, Hôpital Robert-Debré, INSERM NeuroDiderot, DMU Innov-RDB, Neurologie Pédiatrique, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Paris, France. 9. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 1 10. Neurology Epilepsy Unit “Francis Rohmer”, INSERM 1258, FMTS, Strasbourg University, France. -

Research Quarterly

Research Quarterly A dream you dream alone is only a dream. A dream you dream together is reality. – Yoko Ono In this issue of the Quarterly, we highlight some of the partnerships our research team has developed to make a bigger impact for people with epilepsy. Our research covers the entire spectrum of discovery – from idea to market. We cannot do it alone. On page 2, we provide updates on the Rare Epilepsy Network (REN), a coalition of nearly 30 different organizations working together to facilitate research that improves the outcomes of those living with rare epilepsies. On page 3, clinicians from Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, PA reflect on how the Epilepsy Foundation’s support early on in their career encouraged them to pursue research within the field. Supporting the development of early career investigators is done in proud partnership with the American Epilepsy Society (AES). This collaborative effort ensures that we can pool our resources, reduce administrative cost and maximize impact. Supporting our professional workforce is one of the ways in which we can ensure that the best and the brightest are tackling the challenges that our community face. We could not do this without our partners at AES. On page 5, we provide staff reports on the conferences attended this past quarter from the Nonprofits Forum at the National Institutes of Health, to meeting new companies at Bio Conference, to facilitating discussions on how medical devices can impact SUDEP and epilepsy care with the Food and Drug Administration. We are creating a research environment in which partnerships spur innovation and exciting discoveries to end epilepsy. -

Preventive Report Appendix

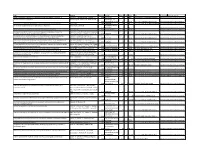

Title Authors Published Journal Volume Issue Pages DOI Final Status Exclusion Reason Nasal sumatriptan is effective in treatment of migraine attacks in children: A Ahonen K.; Hamalainen ML.; Rantala H.; 2004 Neurology 62 6 883-7 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115105.05966.a7 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Seasonal variation in migraine. Alstadhaug KB.; Salvesen R.; Bekkelund SI. Cephalalgia : an 2005 international journal 25 10 811-6 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01018.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Flunarizine, a calcium channel blocker: a new prophylactic drug in migraine. Amery WK. 1983 Headache 23 2 70-4 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1983.hed2302070 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the control of migraine. Anthony M.; Lance JW. Proceedings of the 1970 Australian 7 45-7 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Prostaglandins and prostaglandin receptor antagonism in migraine. Antonova M. 2013 Danish medical 60 5 B4635 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Divalproex extended-release in adolescent migraine prophylaxis: results of a Apostol G.; Cady RK.; Laforet GA.; Robieson randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. WZ.; Olson E.; Abi-Saab WM.; Saltarelli M. 2008 Headache 48 7 1012-25 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01081.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Divalproex sodium extended-release for the prophylaxis of migraine headache in Apostol G.; Lewis DW.; Laforet GA.; adolescents: results of a stand-alone, long-term open-label safety study. Robieson WZ.; Fugate JM.; Abi-Saab WM.; 2009 Headache 49 1 45-53 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01279.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Safety and tolerability of divalproex sodium extended-release in the prophylaxis of Apostol G.; Pakalnis A.; Laforet GA.; migraine headaches: results of an open-label extension trial in adolescents. -

Dravet Syndrome

NAVIGATING LIFE WITH DRAVET SYNDROME Information and support for parents and caregivers NAVIGATING LIFE WITH DRAVET SYNDROME Information and support for parents and caregivers Contributors: Dr. Martina E. Bebin Dr. Robert Flamini Dr. Kelly Knupp Dr. Linda Laux Dr. Scott Perry Dr. Joseph Sullivan Dr. James Wheless Dr. Elaine Wirrell Dravet Syndrome Foundation Executive Team 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 6 Caring for people with Dravet syndrome 24 QUESTIONS 8 14. What should I do when my child 24 has a seizure? Overview of Dravet syndrome 8 15. What are trigger factors for seizures? 25 1. What is Dravet syndrome? 8 16. What daily life difficulties might my 26 2. What is the cause of Dravet syndrome? 10 child face? 3. How is Dravet syndrome diagnosed? 10 Family life 27 4. Is Dravet syndrome inherited? Are my 11 17. How will our family’s daily life change? 27 other children at risk? 18. How do I explain Dravet syndrome 28 5. What type of doctors and specialists 13 to my other children? might my child need to see regularly? 19. How do I explain Dravet syndrome 29 6. Can childhood vaccines cause Dravet 14 to my family and friends? syndrome? Should I vaccinate my child? Dravet syndrome in childhood 31 Seizures and treatments 15 20. What is the course of Dravet syndrome 31 7. What types of seizures are usually 15 in childhood? seen in Dravet syndrome? 21. Can my child attend school? 33 8. What is SUDEP? 16 Dravet syndrome in puberty and adulthood 35 9. Besides seizures, what are the other 18 medical issues related to Dravet syndrome? 22. -

8Th European Congress on Epileptology, Berlin, Germany, 21 – 25 September 2008

Epilepsia, 50(Suppl. 4): 2–262, 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02063.x 8th ECE PROCEEDINGS 8th European Congress on Epileptology, Berlin, Germany, 21 – 25 September 2008 Sunday 21 September 2008 KV7 channels (KV7.1-5) are encoded by five genes (KCNQ1-5). They have been identified in the last 10–15 years by discovering the caus- 14:30 – 16:00 ative genes for three autosomal dominant diseases: cardiac arrhythmia Hall 1 (long QT syndrome, KCNQ1), congenital deafness (KCNQ1 and KCNQ4), benign familial neonatal seizures (BFNS, KCNQ2 and VALEANT PHARMACEUTICALS SATELLITE SYM- KCNQ3), and peripheral nerve hyperexcitability (PNH, KCNQ2). The fifth member of this gene family (KCNQ5) is not affected in a disease so POSIUM – NEURON-SPECIFIC M-CURRENT K+ CHAN- far. The phenotypic spectrum associated with KCNQ2 mutations is prob- NELS: A NEW TARGET IN MANAGING EPILEPSY ably broader than initially thought (i.e. not only BFNS), as patients with E. Perucca severe epilepsies and developmental delay, or with Rolando epilepsy University of Pavia, Italy have been described. With regard to the underlying molecular pathophys- iology, it has been shown that mutations in KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 Innovations in protein biology, coupled with genetic manipulations, have decrease the resulting K+ current thereby explaining the occurrence of defined the structure and function of many of the voltage- and ligand- epileptic seizures by membrane depolarization and increased neuronal gated ion channels, channel subunits, and receptors that are the underpin- firing. Very subtle changes restricted to subthreshold voltages are suffi- nings of neuronal hyperexcitability and epilepsy. Of the currently cient to cause BFNS which proves in a human disease model that this is available antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), no two act in the same way, but all the relevant voltage range for these channels to modulate the firing rate. -

PR2 2009.Vp:Corelventura

Pharmacological Reports Copyright © 2009 2009, 61, 197216 by Institute of Pharmacology ISSN 1734-1140 Polish Academy of Sciences Review Third-generation antiepileptic drugs: mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics and interactions Jarogniew J. £uszczki1,2 Department of Pathophysiology, Medical University of Lublin, Jaczewskiego 8, PL 20-090 Lublin, Poland Department of Physiopathology, Institute of Agricultural Medicine, Jaczewskiego 2, PL 20-950 Lublin, Poland Correspondence: Jarogniew J. £uszczki, e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: This review briefly summarizes the information on the molecular mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetic profiles and drug interac- tions of novel (third-generation) antiepileptic drugs, including brivaracetam, carabersat, carisbamate, DP-valproic acid, eslicar- bazepine, fluorofelbamate, fosphenytoin, ganaxolone, lacosamide, losigamone, pregabalin, remacemide, retigabine, rufinamide, safinamide, seletracetam, soretolide, stiripentol, talampanel, and valrocemide. These novel antiepileptic drugs undergo intensive clinical investigations to assess their efficacy and usefulness in the treatment of patients with refractory epilepsy. Key words: antiepileptic drugs, brivaracetam, carabersat, carisbamate, DP-valproic acid, drug interactions, eslicarbazepine, fluorofelbamate, fosphenytoin, ganaxolone, lacosamide, losigamone, pharmacokinetics, pregabalin, remacemide, retigabine, rufinamide, safinamide, seletracetam, soretolide, stiripentol, talampanel, valrocemide Abbreviations: 4-AP -

Dravet Syndrome—The Polish Family's Perspective Study

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Dravet Syndrome—The Polish Family’s Perspective Study Justyna Paprocka 1,*, Anita Lewandowska 2, Piotr Zieli ´nski 2 , Bartłomiej Kurczab 2, Ewa Emich-Widera 1 and Tomasz Mazurczak 3 1 Department of Pediatric Neurology, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, 40-752 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] 2 Students’ Scientific Society, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, 40-752 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (P.Z.); [email protected] (B.K.) 3 Clinic of Paediatric Neurology, National Research Institute of Mother and Child, 01-211 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Aim: The aim of the paper is to study the prevalence of Dravet Syndrome (DS) in the Polish population and indicate different factors other than seizures reducing the quality of life in such patients. Method: A survey was conducted among caregivers of patients with DS by the members of the Polish support group of the Association for People with Severe Refractory Epilepsy DRAVET.PL. It included their experience of the diagnosis, seizures, and treatment-related adverse effects. The caregivers also completed the PedsQL survey, which showed the most important problems. The survey received 55 responses from caregivers of patients with DS (aged 2–25 years). Results: Prior to the diagnosis of DS, 85% of patients presented with status epilepticus lasting more than 30 min, and the frequency of seizures (mostly tonic-clonic or hemiconvulsions) ranged from 2 per week to hundreds per day. -

A Comparative Effectiveness Meta-Analysis of Drugs for the Prophylaxis of Migraine Headache

University of South Florida Masthead Logo Scholar Commons School of Information Faculty Publications School of Information 7-2015 A Comparative Effectiveness Meta-Analysis of Drugs for the Prophylaxis of Migraine Headache Authors: Jeffrey L. Jackson, Elizabeth Cogbill, Rafael Santana-Davila, Christina Eldredge, William Collier, Andrew Gradall, Neha Sehgal, and Jessica Kuester OBJECTIVE: To compare the effectiveness and side effects of migraine prophylactic medications. DESIGN: We performed a network meta-analysis. Data were extracted independently in duplicate and quality was assessed using both the JADAD and Cochrane Risk of Bias instruments. Data were pooled and network meta-analysis performed using random effects models. DATA SOURCES: PUBMED, EMBASE, Cochrane Trial Registry, bibliography of retrieved articles through 18 May 2014. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR SELECTING STUDIES: We included randomized controlled trials of adults with migraine headaches of at least 4 weeks in duration. RESULTS: Placebo controlled trials included alpha blockers (n = 9), angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (n = 3), angiotensin receptor blockers (n = 3), anticonvulsants (n = 32), beta-blockers (n = 39), calcium channel blockers (n = 12), flunarizine (n = 7), serotonin reuptake inhibitors (n = 6), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (n = 1) serotonin agonists (n = 9) and tricyclic antidepressants (n = 11). In addition there were 53 trials comparing different drugs. Drugs with at least 3 trials that were more effective than placebo for episodic migraines -

10|18 Stiripentol Use in Children with Refractory Seizures

PEDIATRIC PHARMACOTHERAPY Volume 24 Number 10 October 2018 Stiripentol Use in Children with Refractory Seizures Marcia L. Buck, PharmD, FCCP, FPPAG, BCPPS tiripentol was approved by the Food and concentrations of 2, 6.5, and 14.1 mg/L between S Drug Administration (FDA) on August 20, 2 and 4 hours post-dose.6 The drug is highly 2018 as adjunctive therapy with clobazam for the protein bound (99%), with an estimated treatment of seizures associated with Dravet elimination half-life of 5 to 13 hours. Although syndrome in patients 2 years of age and older.1,2 It the metabolism of stiripentol has not been fully is not currently approved as monotherapy. Dravet delineated, it is known to be a substrate for syndrome, also referred to as severe myoclonic CYP1A2, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4. As a result of epilepsy of infancy, is a rare disorder its reliance on both hepatic and renal clearance, characterized by seizures unresponsive to most use of stiripentol in patients with moderate to antiepileptics, motor impairment, and severe hepatic or renal impairment is not developmental disabilities. Nearly a quarter of recommended.2 patients die during childhood. Approximately 70% of patients have a mutation in the sodium The first published study to evaluate stiripentol channel alpha-1 subunit gene (SCN1A) leading to plasma concentrations enrolled 10 children and malfunction or loss of function in GABAergic adolescents from 6 to 16 years of age with neurons.3 As a treatment for a rare disorder, refractory atypical absence seizures.7 The patients stiripentol has been designated as an orphan drug received a mean maintenance dose of 57 by both the European Medicines Agency and the mg/kg/day (range 34-78 mg/kg/day) during the 4- FDA. -

Molecular Mechanisms of Antiseizure Drug Activity at GABAA Receptors

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Seizure 22 (2013) 589–600 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Seizure jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yseiz Review Molecular mechanisms of antiseizure drug activity at GABAA receptors L. John Greenfield Jr.* Dept. of Neurology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301W. Markham St., Slot 500, Little Rock, AR 72205, United States A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: The GABAA receptor (GABAAR) is a major target of antiseizure drugs (ASDs). A variety of agents that act at Received 6 February 2013 GABAARs s are used to terminate or prevent seizures. Many act at distinct receptor sites determined by Received in revised form 16 April 2013 the subunit composition of the holoreceptor. For the benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and loreclezole, Accepted 17 April 2013 actions at the GABAAR are the primary or only known mechanism of antiseizure action. For topiramate, felbamate, retigabine, losigamone and stiripentol, GABAAR modulation is one of several possible Keywords: antiseizure mechanisms. Allopregnanolone, a progesterone metabolite that enhances GABAAR function, Inhibition led to the development of ganaxolone. Other agents modulate GABAergic ‘‘tone’’ by regulating the Epilepsy synthesis, transport or breakdown of GABA. GABAAR efficacy is also affected by the transmembrane Antiepileptic drugs chloride gradient, which changes during development and in chronic epilepsy. This may provide an GABA receptor Seizures additional target for ‘‘GABAergic’’ ASDs. GABAAR subunit changes occur both acutely during status Chloride channel epilepticus and in chronic epilepsy, which alter both intrinsic GABAAR function and the response to GABAAR-acting ASDs. -

Rat Animal Models for Screening Medications to Treat Alcohol Use Disorders

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Selectively Bred Rats Page 1 of 75 Rat Animal Models for Screening Medications to Treat Alcohol Use Disorders Richard L. Bell*1, Sheketha R. Hauser1, Tiebing Liang2, Youssef Sari3, Antoinette Maldonado-Devincci4, and Zachary A. Rodd1 1Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA 2Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA 3University of Toledo, Department of Pharmacology, Toledo, OH 43614, USA 4North Carolina A&T University, Department of Psychology, Greensboro, NC 27411, USA *Send correspondence to: Richard L. Bell, Ph.D.; Associate Professor; Department of Psychiatry; Indiana University School of Medicine; Neuroscience Research Building, NB300C; 320 West 15th Street; Indianapolis, IN 46202; e-mail: [email protected] MANUSCRIPT Key Words: alcohol use disorder; alcoholism; genetically predisposed; selectively bred; pharmacotherapy; family history positive; AA; HAD; P; msP; sP; UChB; WHP Chemical compounds studied in this article Ethanol (PubChem CID: 702); Acamprosate (PubChem CID: 71158); Baclofen (PubChem CID: 2284); Ceftriaxone (PubChem CID: 5479530); Fluoxetine (PubChem CID: 3386); Naltrexone (PubChem CID: 5360515); Prazosin (PubChem CID: 4893); Rolipram (PubChem CID: 5092); Topiramate (PubChem CID: 5284627); Varenicline (PubChem CID: 5310966) ACCEPTED _________________________________________________________________________________ This is the author's manuscript of the article published in final edited form as: Bell, R. L., Hauser, S. R., Liang, T., Sari, Y., Maldonado-Devincci, A., & Rodd, Z. A. (2017). Rat animal models for screening medications to treat alcohol use disorders. Neuropharmacology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.02.004 ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Selectively Bred Rats Page 2 of 75 The purpose of this review is to present animal research models that can be used to screen and/or repurpose medications for the treatment of alcohol abuse and dependence. -

Patent Application Publication ( 10 ) Pub . No . : US 2019 / 0192440 A1

US 20190192440A1 (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No. : US 2019 /0192440 A1 LI (43 ) Pub . Date : Jun . 27 , 2019 ( 54 ) ORAL DRUG DOSAGE FORM COMPRISING Publication Classification DRUG IN THE FORM OF NANOPARTICLES (51 ) Int . CI. A61K 9 / 20 (2006 .01 ) ( 71 ) Applicant: Triastek , Inc. , Nanjing ( CN ) A61K 9 /00 ( 2006 . 01) A61K 31/ 192 ( 2006 .01 ) (72 ) Inventor : Xiaoling LI , Dublin , CA (US ) A61K 9 / 24 ( 2006 .01 ) ( 52 ) U . S . CI. ( 21 ) Appl. No. : 16 /289 ,499 CPC . .. .. A61K 9 /2031 (2013 . 01 ) ; A61K 9 /0065 ( 22 ) Filed : Feb . 28 , 2019 (2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 / 209 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 /2027 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 31/ 192 ( 2013. 01 ) ; Related U . S . Application Data A61K 9 /2072 ( 2013 .01 ) (63 ) Continuation of application No. 16 /028 ,305 , filed on Jul. 5 , 2018 , now Pat . No . 10 , 258 ,575 , which is a (57 ) ABSTRACT continuation of application No . 15 / 173 ,596 , filed on The present disclosure provides a stable solid pharmaceuti Jun . 3 , 2016 . cal dosage form for oral administration . The dosage form (60 ) Provisional application No . 62 /313 ,092 , filed on Mar. includes a substrate that forms at least one compartment and 24 , 2016 , provisional application No . 62 / 296 , 087 , a drug content loaded into the compartment. The dosage filed on Feb . 17 , 2016 , provisional application No . form is so designed that the active pharmaceutical ingredient 62 / 170, 645 , filed on Jun . 3 , 2015 . of the drug content is released in a controlled manner. Patent Application Publication Jun . 27 , 2019 Sheet 1 of 20 US 2019 /0192440 A1 FIG .