American-Cuban by Oscar Medrano Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Fine Arts Degree Kevin Mo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIREWORKS on the FOURTH Malinda Martin

FIREWORKS ON THE FOURTH Malinda Martin Copyright © 2018. Fireworks on The Fourth by Malinda Martin. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the author except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. This is a work of fiction. Names, places, characters, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is purely coincidental. CHAPTER ONE Brandon Crane was in a good mood. As he walked through the little town of Charity, Florida, he knew the surroundings were just what the doctor ordered. The heat of an early June sun was something he was familiar with, coming from New York City. There the concrete jungle magnified the sun’s rays, and along with the sweating mass of millions of people the temperature soared. Here in Florida he was gratified that the town boasted plenty of green space, vibrant trails, and community pools. He couldn’t wait to try them out. He saw Hal’s Place at the end of Main Street and knew from his brother and sister-in-law it was the hangout for any local. Grinning, he reveled in the fact that as of yesterday, he was a local of Charity, Florida. It might have been a huge change from the fast-paced world of New York, but he was ready for it. When the position came available at Charity School, he jumped at the opportunity. Over a thousand miles wasn’t far enough, in his opinion, to be away from the hurt and guilt he’d left behind. -

Casey Jones E------B--8^10--8------G------7^9--7------7------D------10--7--10-----10-- Intro | C / / / | F / C / | = "Casey Jones" Riff A------E

Page 1 Page 2 After Midnight || E7 / / / | G / A / | E 7 / / / | % :|| 7 | E / / / | G / / / | A / / / | B / / / | 7 7 | E / / / | G / A / | E / / / | % | Verse 1 After midnight we're gonna let it all___ hang out. After midnight we're gonna chug-a-lug & shout. We're gonna cause talk and suspicion, Give an exhibition, Find out what it is all about! After midnight we're gonna let it all___ hang out. Verse 2 After midnight we're gonna shake your tambourine. After midnight it's gonna be peaches and cream. We're gonna cause talk and suspicion, Give an exhibition, Find out what it is all about! After midnight we're gonna let it all___ hang out. Lead = Verse Repeated Verse 1 After midnight we're gonna let it all___ hang out. (repeated) After midnight we're gonna chug-a-lug & shout. We're gonna cause talk and suspicion, Give an exhibition, Find out what it is all about! After midnight we're gonna let it all___ hang out. 7 Jam || : E / / / | G / A / :|| Page 3 Aiko-Aiko || : D / / / | % | A / / / | % :|| Chorus Hey Now (Hey Now) , Hey Now (Hey Now) Aiko-Aiko all day Jock-o-mo Fee-no ah-nah-nay, Jock-o-mo fee-nah-nay. Hey Now (Hey Now) , Hey Now (Hey Now) Aiko-Aiko all day Jock-o-mo Fee-no ah-nah-nay, Jock-o-mo fee-nah-nay. Verse 1 My spy boy to your spy boy, they were sittin' along the bayou, My spy boy to your spy boy, I'm gonna set your tail on fire. -

Bob Neumann Prophecies

Bob Neumann Prophecies 7 Moves - 2/1998 - Article/Prophecy A Dream(S) - 4/2001 - Dream A Letter To A Daughter Of Zion - 11/1998 - Prophecy A Little WORD - 3/1998 - Prophecy A Soldier Of The King - 4/1999 - Prophecy A Story Of Three Cities - 11/2004 - Vision A Time To Stand, A Time To Run - 5/2000 - Prophecy A Two Edged Sword - 1/1998 - Prophecy A Walk In The Sun It Is Time - 3/2002 - Vision A Vision And A Word - 1/2005 - Vision About To Recieve - 11/2000 - Article/Prophecy Accountability - 4/1999 - Prophecy/Article American Check Point Charley - Vision Annual Feast Of Football - 1/1999 - Article/Prophecy April Fools - 4/2001 - Article/Word Are The Lights Still Burning In Goshen - 2/1999 - Article/Prophecy Barren Land, Barren People - 5/1999 - Wor/Article Basket Visions - 2/1998 - Article Vision Bitter Harvest - 5/2001 - Vision/Prophecy Building on The ROCK - 2006 - Vision/Article Burn The Bones - 4/2001 - Vision Call it a Dream - 3/2000 - Dream Chosen Vessels - 5/2000 - Prophecy Cynosure (Lesson 1) - 7/2001 - Article/Vision Dead Sheep - 8/1996 - Vision/Prophecy Do You Hear The Drums Beating - 1998 - Dream Don’t You See? - 11/2000 - Vision Double Vision - 7/1998 - Prophecy Dream And Songs - 8/2004 - Dream Echad - 3/1999 - Article/Prophecy Every Word (or The Word) - Prophecy False and True....The Mirror of God - 5/1999 - Vision/Prophecy For Keeps - 10/2000 - Prophecy Go Tell The Chosen - 2/2012 - Prophecy Harpezo - 7/1999 - Prophecy Holy Of Holies - 2/1999 - Prophecy I Grieve - 2/1998 - Prophecy I Must Be Poured Out - 12/1997 - Prophecy -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

English Songs

English Songs 18000 04 55-Vũ Luân-Thoại My 18001 1 2 3-Gloria Estefan 18002 1 Sweet Day-Mariah Carey Boyz Ii M 18003 10,000 Promises-Backstreet Boys 18004 1999-Prince 18005 1everytime I Close My Eyes-Backstr 18006 2 Become 1-Spice Girls 18007 2 Become 1-Unknown 18008 2 Unlimited-No Limit 18009 25 Minutes-Michael Learns To Rock 18010 25 Minutes-Unknown 18011 4 gio 55-Wynners 18012 4 Seasons Of Lonelyness-Boyz Ii Me 18013 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover-Paul S 18014 500 Miles Away From Home-Peter Pau 18015 500 Miles-Man 18016 500 Miles-Peter Paul-Mary 18017 500 Miles-Unknown 18018 59th Street Bridge Song-Classic 18019 6 8 12-Brian McKnight 18020 7 Seconds-Unknown 18021 7-Prince 18022 9999999 Tears-Unknown 18023 A Better Love Next Time-Cruise-Pa 18024 A Certain Smile-Unknown 18025 A Christmas Carol-Jose Mari Chan 18026 A Christmas Greeting-Jeremiah 18027 A Day In The Life-Beatles-The 18028 A dear John Letter Lounge-Cardwell 18029 A dear John Letter-Jean Sheard Fer 18030 A dear John Letter-Skeeter Davis 18031 A dear Johns Letter-Foxtrot 18032 A Different Beat-Boyzone 18033 A Different Beat-Unknown 18034 A Different Corner-Barbra Streisan 18035 A Different Corner-George Michael 18036 A Foggy Day-Unknown 18037 A Girll Like You-Unknown 18038 A Groovy Kind Of Love-Phil Collins 18039 A Guy Is A Guy-Unknown 18040 A Hard Day S Night-The Beatle 18041 A Hard Days Night-The Beatles 18042 A Horse With No Name-America 18043 À La Même Heure Dans deux Ans-Fema 18044 A Lesson Of Love-Unknown 18045 A Little Bit Of Love Goes A Long W- 18046 A Little Bit-Jessica -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Jimmy Rankin – Back Road Paradise • Enrique

Jimmy Rankin – Back Road Paradise Enrique Iglesias – Sex And Love Avicii – True: Avicii By Avicii New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI14-11 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Stompin’ Tom Connors / Unreleased: Songs From The Vault Collection Volume 1 Cat. #: 0253777712 Price Code: SP Order Due: March 6, 2014 Release Date: April 1, 2014 File: Country Genre Code: 16 Box Lot: 25 Tracks / not final sequence 6 02537 77712 9 Tom and Guitar: 12 songs 10. I'll Sail My Ship Alone 1. Blue Ranger 11. When My Blue Moon Turns to Gold 2. Rattlin' Cannonball 12. I Overlooked an Orchid 3. Turkey in The straw ( Instrumental ) 4. John B. Sails Tom Originals with Band: 5. Truck Drivin' Man 1. Cross Canada, aka C.A.N.A.D.A 6. Wild Side of Life 2. My Stompin' Grounds 7. Pawn Shop in Pittsburgh, aka, Pittsburgh 3. Movin' In From Montreal By Train Pennsylvania 4. Flyin' C.P.R. 8. Nobody's Child 5. Ode for the Road 9. Darktown Strutter's Ball This is the Premier Release in an upcoming series of Unreleased Material by Stompin' Tom Connors! In 2011, Tom decided after what ended up being his final Concert Tour, that he would record another 10 album set with a lot of old songs that he sang when he first started out performing in the 50's and 60's.This was back when he could sing, from memory, over 2500 songs in his repertoire and long before he wrote many of his own hits we all know today. -

Lessons Learned: a Crisis Responder‟S Journey Supporting Friends in Crisis

LESSONS LEARNED: A CRISIS RESPONDER‟S JOURNEY SUPPORTING FRIENDS IN CRISIS A Dissertation by TINA SWANSON BROOKES Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August 2011 Doctoral Program in Educational Leadership LESSONS LEARNED: A CRISIS RESPONDER‟S JOURNEY SUPPORTING FRIENDS IN CRISIS A Dissertation by TINA SWANSON BROOKES August 2011 APPROVED BY: ______________________________________________ Roma B. Angel, Ed.D. Co-Chair, Dissertation Committee ______________________________________________ Vachel W. Miller, Ed.D. Co-Chair, Dissertation Committee ______________________________________________ Leslie S. Cook, Ph.D. Member, Dissertation Committee ______________________________________________ Jim Killacky, Ed.D. Director, Doctoral Program in Educational Leadership ______________________________________________ Edelma D. Huntley, Ph.D. Dean, Research and Graduate Studies Copyright by Tina Swanson Brookes 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT LESSONS LEARNED: A CRISIS RESPONDER‟S JOURNEY SUPPORTING FRIENDS IN CRISIS (August 2011) Tina Swanson Brookes, B.A., Anderson College M.S.W., Indiana University, Indianapolis Ed.S., Appalachian State University Co-Chairpersons: Roma Angel and Vachel Miller Crisis is an educational leadership concern as evidenced by crises that have impacted schools like 9-11, the rampage shootings at Columbine High School, and Hurricane Katrina. Educational leaders experience crisis on both personal and professional levels. This dissertation is my Scholarly Personal Narrative (SPN) about my journey as an educational leader in crisis response who supported friends in crisis. This dissertation is framed by literature related to chaos theory and crisis response. Crisis responders have friends and some of those friends will at some time experience a crisis. Yet, there is limited scholarly literature about crisis responders supporting friends in crisis. -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People.. -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) This is Pop…XTC (3/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Airport…Motors (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) Roxanne…The Police (2/79) Lucky Number (slavic dance version)…Lene Lovich (3/79) Good Times Roll…The Cars (3/79) Dance -

Chipps E-Journal Pediatric Palliative and Hospice Care Issue #51; May, 2018

Offering Support in Crisis/Traumatic Situations Issue #51, May 2018 1 ChiPPS E-Journal Pediatric Palliative and Hospice Care Issue #51; May, 2018 Issue Topic: Offering Support in Crisis/Traumatic Situations Welcome to the 51st issue of the ChiPPS E-Journal. This issue of our E-Journal explores topics related to offering support in crisis or traumatic situations. Professionals and volunteers whose primary work involves caring for children, adolescents, and families in pediatric hospice and palliative care programs occasionally find themselves confronted with crisis or traumatic situations in the communities they serve. How can professionals and volunteers best respond to such situations? How can they best prepare themselves to be helpful in these encounters? This issue seeks to provide at least a beginning in discussing these matters. This E-Journal is produced by ChiPPS (the Children’s Project on Palliative/Hospice Services), a program of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization and, in particular, by ChiPPS’s E-Journal Workgroup, co-chaired by Christy Torkildson and Ann Fitzsimons. Archived issues of this publication are available at www.nhpco.org/pediatrics. Comments about the activities of ChiPPS, its E-Journal Workgroup, or this issue are welcomed. We also encourage readers to suggest topics, contributors, and specific ideas for future issues. Our tentative plan for the remainder of 2018 is to develop issues on caring for diverse families/populations, as well as adolescents and young adults. If you have any thoughts about these topics, contributors, or future issues, please contact Christy at [email protected] or Ann at [email protected] Produced by the ChiPPS E-Journal Work Group Charles A. -

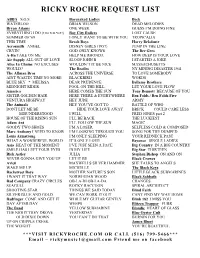

Ricky Roche Request List

RICKY ROCHE REQUEST LIST ABBA S.O.S. Barenaked Ladies Beck WATERLOO BRIAN WILSON DEAD MELODIES Bryan Adams ONE WEEK GUESS I’M DOING FINE EVERYTHING I DO (I DO FOR YOU) Bay City Rollers LOST CAUSE SUMMER OF '69 I ONLY WANT TO BE WITH YOU TROPICALIA THIS TIME Beach Boys Harry Belafonte Aerosmith ANGEL DISNEY GIRLS (1957) JUMP IN THE LINE CRYIN’ GOD ONLY KNOWS The Bee Gees A-Ha TAKE ON ME HELP ME RHONDA HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE Air Supply ALL OUT OF LOVE SLOOP JOHN B I STARTED A JOKE Alice In Chains NO EXCUSES WOULDN’T IT BE NICE MASSACHUSETTS WOULD? The Beatles NY MINING DISASTER 1941 The Allman Bros ACROSS THE UNIVERSE TO LOVE SOMEBODY AINT WASTIN TIME NO MORE BLACKBIRD WORDS BLUE SKY * MELISSA DEAR PRUDENCE Bellamy Brothers MIDNIGHT RIDER FOOL ON THE HILL LET YOUR LOVE FLOW America HERE COMES THE SUN Tony Bennett BECAUSE OF YOU SISTER GOLDEN HAIR HERE THERE & EVERYWHERE Ben Folds / Ben Folds Five VENTURA HIGHWAY HEY JUDE ARMY The Animals HEY YOU’VE GOT TO BATTLE OF WHO DONT LET ME BE HIDE YOUR LOVE AWAY BRICK COULD CARE LESS MISUNDERSTOOD I WILL FRED JONES part 2 HOUSE OF THE RISING SUN I’LL BE BACK THE LUCKIEST Adam Ant I’LL FOLLOW THE SUN MAGIC GOODY TWO SHOES I’M A LOSER SELFLESS COLD & COMPOSED Marc Anthony I NEED TO KNOW I’M LOOKING THROUGH YOU SONG FOR THE DUMPED Louis Armstrong I’M ONLY SLEEPING YOUR REDNECK PAST WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD IT’S ONLY LOVE Beyonce SINGLE LADIES Asia HEAT OF THE MOMENT I’VE JUST SEEN A FACE Big Country IN A BIG COUNTRY SMILE HAS LEFT YOUR EYES IN MY LIFE Big Star THIRTEEN Rick Astley JULIA Stephen Bishop -

Agudua Owiwi

Agudua Owiwi DRAMA Kraftgriots Also in the series (DRAMA) Rasheed Gbadamosi: Trees Grow in the Desert Rasheed Gbadamosi: 3 Plays Akomaye Oko: The Cynic Chris Nwamuo: The Squeeze & Other Plays Olu Obafemi: Naira Has No Gender Chinyere Okafor: Campus Palavar & Other Plays Chinyere Okafor: The Lion and the Iroko Ahmed Yerima: The Silent Gods Ebereonwu: Cobweb Seduction Ahmed Yerima: Kaffir’s Last Game Ahmed Yerima: The Bishop & the Soul with Thank You Lord Ahmed Yerima: The Trials of Oba Ovonramwen Ahmed Yerima: Attahiru Ahmed Yerima: The Sick People (2000) Omome Anao: Lions at War & Other Plays (2000) Ahmed Yerima: Dry Leaves on Ukan Trees (2001) Ahmed Yerima: The Sisters (2001) Niyi Osundare: The State Visit (2002) Ahmed Yerima: Yemoja (2002) Ahmed Yerima: The Lottery Ticket (2002) Muritala Sule: Wetie (2003) Ahmed Yerima: Otaelo (2003) Ahmed Yerima: The Angel & Other Plays (2004) Ahmed Yerima: The Limam & Ade Ire (2004) Onyebuchi Nwosu: Bleeding Scars (2005) Ahmed Yerima: Ameh Oboni the Great (2006) Femi Osofisan: Fiddlers on a Midnight Lark (2006) Ahmed Yerima: Hard Ground (2006), winner, The Nigeria Prize for Literature, 2006 and winner, ANA/NDDC J.P. Clark Drama Prize, 2006 Ahmed Yerima: Idemili (2006) Ahmed Yerima: Erelu-Kuti (2006) Austine E. Anigala: Cold Wings of Darkness (2006) Austine E. Anigala: The Living Dead (2006) Felix A. Akinsipe: Never and Never (2006) Ahmed Yerima: Aetu (2007) Chukwuma Anyanwu: Boundless Love (2007) Ben Binebai: Corpers’ Verdict (2007) John Iwuh: The Village Lamb (2007), winner, ANA/NDDC J.P. Clark Drama