Butterfly Pollination and High-Contrast Visual Signals in a Low-Density Distylous Plant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mussaendas for South Florida Landscapes

MUSSAENDAS FOR SOUTH FLORIDA LANDSCAPES John McLaughlin* and Joe Garofalo* Mussaendas are increasingly popular for the surrounding calyx has five lobes, with one lobe showy color they provide during much of the year conspicuously enlarged, leaf-like and usually in South Florida landscapes. They are members brightly colored. In some descriptions this of the Rubiaceae (madder or coffee family) and enlarged sepal is termed a calycophyll. In many are native to the Old World tropics, from West of the cultivars all five sepals are enlarged, and Africa through the Indian sub-continent, range in color from white to various shades of Southeast Asia and into southern China. There pink to carmine red. are more than 200 known species, of which about ten are found in cultivation, with three of these There are a few other related plants in the being widely used for landscaping. Rubiaceae that also possess single, enlarged, brightly colored sepals. These include the so- called wild poinsettia, Warszewiczia coccinea, DESCRIPTION. national flower of Trinidad; and Pogonopus The mussaendas used in landscapes are open, speciosus (Chorcha de gallo)(see Figure 1). somewhat scrambling shrubs, and range from 2-3 These are both from the New World tropics and ft to 10-15 ft in height, depending upon the both are used as ornamentals, though far less species. In the wild, some can climb 30 ft into frequently than the mussaendas. surrounding trees, though in cultivation they rarely reach that size. The fruit is a small (to 3/4”), fleshy, somewhat elongated berry containing many seeds. These Leaves are opposite, bright to dark green, and are rarely seen under South Florida conditions. -

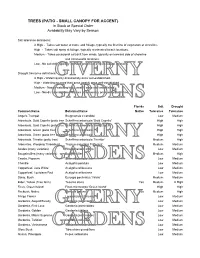

TREES (PATIO - SMALL CANOPY for ACCENT) in Stock Or Special Order Availability May Vary by Season

TREES (PATIO - SMALL CANOPY FOR ACCENT) In Stock or Special Order Availability May Vary by Season Salt tolerance definitions: X High - Takes salt water at roots and foliage, typically the first line of vegetation at shoreline. High - Takes salt spray at foliage, typically at elevated beach locations. Medium - Takes occasional salt drift from winds, typically on leeward side of shoreline and intracoastal locations. Low - No salt drift, typically inland or protected area of coastal locations. Drought tolerance definitions: X High - Watering only occasionally once well-established. High - Watering no more than once weekly once well-established. Medium - Needs watering twice weekly once well-established. Low - Needs watering three or more times weekly once well-established. Florida Salt Drought Common Name Botanical Name Native Tolerance Tolerance Angel's Trumpet Brugmansia x candida Low Medium Arboricola, Gold Capella (patio tree) Schefflera arboricola 'Gold Capella' High High Arboricola, Gold Capella (patio tree braided)Schefflera arboricola 'Gold Capella' High High Arboricola, Green (patio tree) Schefflera arboricola High High Arboricola, Green (patio tree braided)Schefflera arboricola High High Arboricola, Trinette (patio tree) Schefflera arboricola 'Trinette' Medium High Arborvitae, Weeping Threadleaf Thuja occidentalis 'Filiformis' Medium Medium Azalea (many varieties) Rhododrendon indica Low Medium Bougainvillea {many varieties) Bougainvillea x Medium High Cassia, Popcorn Senna didymobotrya Low Medium Chenille Acalypha pendula Low -

Responses of Ornamental Mussaenda Species Stem Cuttings to Varying Concentrations of Naphthalene Acetic Acid Phytohormone Application

GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2017, 01(01), 020–024 Available online at GSC Online Press Directory GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences e-ISSN: 2581-3250, CODEN (USA): GBPSC2 Journal homepage: https://www.gsconlinepress.com/journals/gscbps (RESEARCH ARTICLE) Responses of ornamental Mussaenda species stem cuttings to varying concentrations of naphthalene acetic acid phytohormone application Ogbu Justin U. 1*, Okocha Otah I. 2 and Oyeleye David A. 3 1 Department of Horticulture and Landscape technology, Federal College of Agriculture (FCA), Ishiagu 491105 Nigeria. 2 Department of Horticulture technology, AkanuIbiam Federal Polytechnic, Unwana Ebonyi state Nigeria. 3 Department of Agricultural technology, Federal College of Agriculture (FCA), Ishiagu 491105 Nigeria Publication history: Received on 28 August 2017; revised on 03 October 2017; accepted on 09 October 2017 https://doi.org/10.30574/gscbps.2017.1.1.0009 Abstract This study evaluated the rooting and sprouting responses of four ornamental Mussaendas species (Flag bush) stem cuttings to treatment with varying concentrations of 1-naphthalene acetic acid (NAA). Species evaluated include Mussaenda afzelii (wild), M. erythrophylla, M. philippica and Pseudomussaenda flava. Different concentrations of NAA phytohormone were applied to the cuttings grown in mixed river sand and saw dust (1:1; v/v); and laid out in a 4 x 4 factorial experiment in completely randomized design (CRD; r=4). Results showed that increasing concentrations of NAA application slowed down emerging shoot bud in M. afzelii, P. flava, M. erythrophylla and M. philippica. While other species responded positively at some point to increased concentrations of the NAA applications, the P. flava showed retarding effect of phytohormone treatment on its number of leaves. -

Fl. China 19: 231–242. 2011. 56. MUSSAENDA Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1

Fl. China 19: 231–242. 2011. 56. MUSSAENDA Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 177. 1753. 玉叶金花属 yu ye jin hua shu Chen Tao (陈涛); Charlotte M. Taylor Belilla Adanson. Trees, shrubs, or clambering or twining lianas, rarely dioecious, unarmed. Raphides absent. Leaves opposite or occasionally in whorls of 3, with or usually without domatia; stipules persistent or caducous, interpetiolar, entire or 2-lobed. Inflorescences terminal and sometimes also in axils of uppermost leaves, cymose, paniculate, or thyrsiform, several to many flowered, sessile to pedunculate, bracteate. Flowers sessile to pedicellate, bisexual and usually distylous or rarely unisexual. Calyx limb 5-lobed nearly to base, fre- quently some or all flowers of an inflorescence with 1(–5) white to colored, petaloid, persistent or deciduous, membranous, stipitate calycophyll(s) with 3–7 longitudinal veins. Corolla yellow, red, orange, white, or rarely blue (Mussaenda multinervis), salverform with tube usually slender then abruptly inflated around anthers, or rarely constricted at throat (M. hirsuta), inside variously pubescent but usually densely yellow clavate villous in throat; lobes 5, valvate-reduplicate in bud, often long acuminate. Stamens 5, inserted in middle to upper part of corolla tube, included; filaments short or reduced; anthers basifixed. Ovary 2-celled, ovules numerous in each cell, inserted on oblong, fleshy, peltate, axile placentas; stigmas 2-lobed, lobes linear, included or exserted. Fruit purple to black, baccate or perhaps rarely capsular (M. decipiens), fleshy, globose to ellipsoid, often conspicuously lenticellate, with calyx limb per- sistent or caducous often leaving a conspicuous scar; seeds numerous, small, angled to flattened; testa foveolate-striate; endosperm abundant, fleshy. -

DROUGHT TOLERANT PLANT PALETTE in Stock Or Special Order Availability May Vary by Season

DROUGHT TOLERANT PLANT PALETTE In Stock or Special Order Availability May Vary by Season Salt tolerance definitions: X High - Takes salt water at roots and foliage, typically the first line of vegetation at shoreline. High - Takes salt spray at foliage, typically at elevated beach locations. Medium - Takes occasional salt drift from winds, typically on leeward side of shoreline and intracoastal locations. Low - No salt drift, typically inland or protected area of coastal locations. Drought tolerance definitions: X High - Watering only occasionally once well-established. High - Watering no more than once weekly once well-established. Medium - Needs watering twice weekly once well-established. Low - Needs watering three times or more weekly once well-established. Florida Salt Drought Palms Native Tolerance Tolerance Adonidia Adonidia merrillii Medium High Alexander Ptychosperma elegans Low High Arikury Syagrus schizophylla Medium High Bamboo Palm Chamaedorea seifrizii Low High Bismarkia Bismarkia nobilis High High Bottle Hyophorbe lagenicaulis High High Buccaneer Pseudophoenix sargentii Yes High X High Cabada Dypsis cabadae Medium High Cat Chamaedorea cataractum Low Medium Chinese Fan Livistonia chinensis Medium High Coconut Cocos nucifera X High High European Fan Chamaerops humilis Low High Fishtail Caryota mitis Low High Florida Thatch Thrinax radiata Yes High High Foxtail Wodyetia bifurcata Medium High Hurricane Dictyosperma album High High Lady Palm Rhapis excelsa Low Medium Licuala Licuala grandis Low Medium Majesty Ravenea rivularis -

2011 Vol. 14, Issue 3

Department of Botany & the U.S. National Herbarium The Plant Press New Series - Vol. 14 - No. 3 July-September 2011 Island Explorations and Evolutionary Investigations By Vinita Gowda or over a century the Caribbean eastward after the Aves Ridge was formed On joining the graduate program region, held between North and to the West. Although the Lesser Antilles at The George Washington University FSouth America, has been an active is commonly referred to as a volcani- in Washington, D.C., in the Fall of area of research for people with interests cally active chain of islands, not all of the 2002, I decided to investigate adapta- in island biogeography, character evolu- Lesser Antilles is volcanic. Based on geo- tion in plant-pollinator interactions tion, speciation, as well as geology. Most logical origin and elevation all the islands using a ‘multi-island’ comparative research have invoked both dispersal and of the Lesser Antilles can be divided into approach using the Caribbean Heliconia- vicariance processes to explain the distri- two groups: a) Limestone Caribbees (outer hummingbird interactions as the study bution of the local flora and fauna, while arc: calcareous islands with a low relief, system. Since I was interested in under- ecological interactions such as niche dating to middle Eocene to Pleistocene), standing factors that could influence partitioning and ecological adaptations and b) Volcanic Caribbees (inner arc: plant-pollinator mutualistic interactions have been used to explain the diversity young volcanic islands with strong relief, between the geographically distinct within the Caribbean region. One of dating back to late Miocene). islands, I chose three strategic islands of the biggest challenges in understanding the Lesser Antilles: St. -

Evaluation of a New Tablet Excipient from the Leaves of Mussaenda Frondosa Linn

ISSN: 0975-8585 Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences Evaluation of a new tablet excipient from the leaves of Mussaenda frondosa Linn. Dilip C * Ameena K, Saraswathi R, Krishnan PN, Simi SP, Sanker C Al Shifa College of Pharmacy, Kizhattur, Perinthalmanna, Kerala, 679325, India. ABSTRACT Mussaenda frondosa Linn, family, Rubiacae, traditionally used in Indian folk medicine. Here an effort was made to investigate the efficacy of the mucilage obtained from the leaves of Mussaenda frondosa Linn as tablet excipient. The mucilage extracted from the leaves of Mussaenda frondosa Linn and studied for various physicochemical properties. Tablets were manufactured using extracted mucilage as the binding agent and comparison was made against the tablets prepared with starch paste as the standard binder on studying the standard parameters like diameter, thickness, weight variation, hardness, friability, disintegration and in-vitro dissolution study. Stability studies were conducted for 4 weeks periods.The mucilage shows good physicochemical properties that assessed as an excipient in formulation of tablets. The tablets prepared by using 5-10% mucilage shows the release rate in a sustained manner and that of 1% shows the drug release more than 90% within 4 h, which can be considered as the ideal concentration for preparation of tablets. At the end of 4th week appreciable changes was not observed for the stability study. Mussaenda frondosa mucilage could be used as a good binding agent at very low concentrations. This can be used for sustaining the drug release from tablets, since the prepared tablets produced a sticky film of hydration on the surface, which ultimately reduces drug release rate and hence it can be evaluated for its efficacy to sustain the drug release. -

Molecular Support for a Basal Grade of Morphologically

TAXON 60 (4) • August 2011: 941–952 Razafimandimbison & al. • A basal grade in the Vanguerieae alliance MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND BIOGEOGRAPHY Molecular support for a basal grade of morphologically distinct, monotypic genera in the species-rich Vanguerieae alliance (Rubiaceae, Ixoroideae): Its systematic and conservation implications Sylvain G. Razafimandimbison,1 Kent Kainulainen,1,2 Khoon M. Wong, 3 Katy Beaver4 & Birgitta Bremer1 1 Bergius Foundation, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and Botany Department, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 2 Department of Botany, Stockholm University, 10691, Stockholm, Sweden 3 Singapore Botanic Gardens, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569 4 Plant Conservation Action Group, P.O. Box 392, Victoria, Mahé, Seychelles Author for correspondence: Sylvain G. Razafimandimbison, [email protected] Abstract Many monotypic genera with unique apomorphic characters have been difficult to place in the morphology-based classifications of the coffee family (Rubiaceae). We rigorously assessed the subfamilial phylogenetic position and generic status of three enigmatic genera, the Seychellois Glionnetia, the Southeast Asian Jackiopsis, and the Chinese Trailliaedoxa within Rubiaceae, using sequence data of four plastid markers (ndhF, rbcL, rps16, trnTF). The present study provides molecular phylogenetic support for positions of these genera in the subfamily Ixoroideae, and reveals the presence of a basal grade of morphologically distinct, monotypic genera (Crossopteryx, Jackiopsis, Scyphiphora, Trailliaedoxa, and Glionnetia, respectively) in the species-rich Vanguerieae alliance. These five genera may represent sole representatives of their respective lineages and therefore may carry unique genetic information. Their conservation status was assessed, applying the criteria set in IUCN Red List Categories. We consider Glionnetia and Jackiopsis Endangered. Scyphiphora is recognized as Near Threatened despite its extensive range and Crossopteryx as Least Concern. -

Mussaenda Lancipetala X. F. Deng & D. X. Zhang, a New Species Of

Journal of Systematics and Evolution 46 (2): 220–225 (2008) doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1002.2008.07021 (formerly Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica) http://www.plantsystematics.com Mussaenda lancipetala X. F. Deng & D. X. Zhang, a new species of Rubiaceae from China 1,2Xiao-Fang DENG 1Dian-Xiang ZHANG* 1(South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China) 2(Institute of Agro-Environmental Protection, Ministry of Agriculture of China, Tianjin 300191, China) Abstract Mussaenda lancipetala X. F. Deng & D. X. Zhang, a new species of Rubiaceae from Yunnan Prov- ince, Southwestern China, is described and illustrated. The new species is characterized by its reverse herkoga- mous sexual system, its ovate-lanceolate corolla lobes with caudate apex, and corolla tube covered with sparse farinose pubescence, by which it is clearly distinguished from other species of Mussaenda. Key words Mussaenda, Mussaenda lancipetala X. F. Deng & D. X. Zhang, new species, pollen morphology, sexual system, taxonomy. Mussaenda L. s.s. is a paleotropical genus of ca. cence out of the corolla tube. The pollen and leaf 132 species (Alejandro et al., 2005), with ca. 30 epidermal morphology, gross morphology of the species occurring in China (Hsue & Wu, 1999). Spe- species is different from the known taxa, and a new cies in Mussaenda are characterized by having species, M. lancipetala, was eventually proposed. enlarged petaloid calyx lobes, valvate-reduplicate aestivation of the corolla lobes and indehiscent, berry-like fruits, and the woody, scandent or liana 1 Material and Methods habit. The generic circumscriptions have always been Field studies were undertaken by the authors in controversial since the genus was established (Bremer 2005 and also in 2006 in Yunnan Province, China, and & Thulin, 1998; Huysmans et al., 1998; Puff et al., specimens from HITBC, IBSC, KUN and PE and 1993; Robbrecht, 1988; Li, 1943; Wernham, 1916). -

Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Mussaenda Species (Rubiaceae)

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 12: 469-475. 2008. Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Mussaenda Species (Rubiaceae) K.S.Vidyalakshmi,1 Hannah R.Vasanthi,3 G.V.Rajamanickam2 1Department of Chemistry, PRIST University, Thanjavur. 2Centre For Advanced Research In Indian System of Medicine, SASTRA University, Thanjavur, Tamilnadu, India. 3Department of Biochemistry, Sri Ramachandra University, Porur, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India Issued 2 July 2008 Abstract The genus Mussaenda is an important source of medicinal natural products, particularly iridoids, triterpenes and flavonoids. The purpose of this paper is to cover the more recent developments in the ethnobotany, pharmacology and phytochemistry of this genus. The species in which the largest number of compounds has been identified is Mussaenda pubescens. Pharmacological studies have also been made, however, of other species in this genus. These lesser known plants of the genus are described here according to their cytotoxicity, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antioxidant and antibacterial properties. The information given here is intended to serve as a reference tool for practitioners in the fields of ethnopharmacology and natural products chemistry. Key words: Mussaenda; Rubiaceae; Mussaein; antifertility. Introduction One way in which the study of medicinal plants has progressed is in the discovery of bioactive compounds from new promising drug species. In this respect, the genus Mussaenda has been important in providing us with several natural products of interest to workers in the field of pharmacology. The species of this genus have the further advantage of being easy to grow. They are pest and disease free and can withstand heavy pruning. Very few species have been explored for chemical and biological studies. -

Cai Thesis.Pdf

Lianas and trees in tropical forests in south China Lianen en bomen in tropisch bos in zuid China Promotor: Prof. Dr. F.J.J.M. Bongers Persoonlijk hoogleraar bij de leerstoelgroep Bosecologie en bosbeheer Wageningen Universiteit Co-promotor: Prof. Dr. K-F. Cao Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden Chinese Academy of Sciences, Yunnan, China Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Prof. Dr. L.H.W. van der Plas, Wageningen Universiteit Prof. Dr. M.J.A. Werger, Universiteit Utrecht Dr. H. Poorter, Universiteit Utrecht Dr. S.A. Schnitzer, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, USA Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de C.T. de Wit onderzoeksschool Production Ecology & Resource Conservation (PE&RC), Wageningen Universiteit en Researchcentrum. Lianas and trees in tropical forests in south China Zhi-quan Cai Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. Dr. M.J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 28 maart 2007 des namiddags te 16.00 uur in de Aula Cai, Z-Q (2007) Lianas and trees in tropical forests in south China. PhD thesis, Department of Environmental Sciences, Centre for Ecosystem Studies, Forest Ecology and forest Management Group, Wageningen University, the Netherlands. Keywords: lianas, trees, liana-tree interaction, plant morphology, plant ecophysiology, growth, biodiversity, south China, Xishuangbanna ISBN 978-90-8504-653-0 This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation in China (grant no. 30500065) and a sandwich-PhD grant from Wageningen -

Glycosides in the Rubiaceae*

The occurrence of asperulosidic glycosides in the Rubiaceae* P. Kooiman Laboratorium voor Algemene en Technische Biologie Technische Hogeschool, Delft. SUMMARY Some properties of the new iridoid compounds Galium glucoside and Gardenia glucoside are described. Galium glucoside and asperuloside occurin many species belongingto the Rubioideae (sensu Bremekamp); they were not found in other subfamilies of the Rubiaceae. Gardenia glucoside occurs in several species ofthe tribe Gardenieae (subfamily Ixoroideae). The distribution of the asperulosidic glucosides in the Rubiaceae corresponds with the classi- fication proposed by Bremekamp, although there are some exceptions (Hamelieae, Opercu- laria and Pomax, possibly the Gaertnereae). To a somewhat less degreethe system proposedby Verdcourt is supported. 1. INTRODUCTION Apart from the classification arrived at by Bremekamp (1966) the only other modern system of the Rubiaceae was proposed by Verdcourt (1958); both au- thors considered their classifications tentative. The have several fea- as systems tures in common, but deviate in some points. The main differences are in the po- sition ofthe Urophylloideae sensu Bremekamp, which are included in the subfa- mily Rubioideaeby Verdcourt, and in the relationship between the Cinchonoideae the Ixoroideae and (both sensu Bremekamp) which are united in the subfamily Cinchonoideae by Verdcourt. Both systems diverge widely and principally from all older classifications which appeared to become more and more unsatis- factory as the number of described species increased. In 1954 Briggs & Nicholes reported on the presence or absence of the iridoid glucoside asperuloside (1) in most species of Coprosma and in many other Rubiaceae. The reaction they used for the detection of asperuloside is now known to be not specific for this glucoside; it detects in addition some struc- turally and most probably biogenetically related glycosides.