House Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1990 NGA Annual Meeting

BARLOW & JONES P.O. BOX 160612 MOBILE, ALABAMA 36616 (205) 476-0685 ~ 1 2 ACHIEVING EDUCATIONAL EXCELLENCE 3 AND ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 4 5 National Governors' Association 6 82nd Annual Meeting Mobile, Alabama 7 July 29-31, 1990 8 9 10 11 12 ~ 13 ..- 14 15 16 PROCEEDINGS of the Opening Plenary Session of the 17 National Governors' Association 82nd Annual Meeting, 18 held at the Mobile Civic Center, Mobile, Alabama, 19 on the 29th day of July, 1990, commencing at 20 approximately 12:45 o'clock, p.m. 21 22 23 ".~' BARLOW & JONES P.O. BOX 160612 MOBILE. ALABAMA 36616 (205) 476-0685 1 I N D E X 2 3 Announcements Governor Branstad 4 Page 4 5 6 Welcoming Remarks Governor Hunt 7 Page 6 8 9 Opening Remarks Governor Branstad 10 Page 7 11 12 Overview of the Report of the Task Force on Solid Waste Management 13 Governor Casey Governor Martinez Page 11 Page 15 14 15 Integrated Waste Management: 16 Meeting the Challenge Mr. William D. Ruckelshaus 17 Page 18 18 Questions and Discussion 19 Page 35 20 21 22 23 2 BARLOW & JONES P.O. BOX 160612 MOBILE, ALABAMA 36616 (205) 476-0685 1 I N D E X (cont'd) 2 Global Environmental Challenges 3 and the Role of the World Bank Mr. Barber B. Conable, Jr. 4 Page 52 5 Questions and Discussion 6 Page 67 7 8 Recognition of NGA Distinguished Service Award Winners 9 Governor Branstad Page 76 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 3 BARLOW & JONES P.O. -

POLL RESULTS: Congressional Bipartisanship Nationwide and in Battleground States

POLL RESULTS: Congressional Bipartisanship Nationwide and in Battleground States 1 Voters think Congress is dysfunctional and reject the suggestion that it is effective. Please indicate whether you think this word or phrase describes the United States Congress, or not. Nationwide Battleground Nationwide Independents Battleground Independents Dysfunctional 60 60 61 64 Broken 56 58 58 60 Ineffective 54 54 55 56 Gridlocked 50 48 52 50 Partisan 42 37 40 33 0 Bipartisan 7 8 7 8 Has America's best 3 2 3 interests at heart 3 Functioning 2 2 2 3 Effective 2 2 2 3 2 Political frustrations center around politicians’ inability to collaborate in a productive way. Which of these problems frustrates you the most? Nationwide Battleground Nationwide Independents Battleground Independents Politicians can’t work together to get things done anymore. 41 37 41 39 Career politicians have been in office too long and don’t 29 30 30 30 understand the needs of regular people. Politicians are politicizing issues that really shouldn’t be 14 13 12 14 politicized. Out political system is broken and doesn’t work for me. 12 15 12 12 3 Candidates who brand themselves as bipartisan will have a better chance of winning in upcoming elections. For which candidate for Congress would you be more likely to vote? A candidate who is willing to compromise to A candidate who will stay true to his/her get things done principles and not make any concessions NationwideNationwide 72 28 Nationwide Nationwide Independents Independents 74 26 BattlegroundBattleground 70 30 Battleground Battleground IndependentsIndependents 73 27 A candidate who will vote for bipartisan A candidate who will resist bipartisan legislation legislation and stick with his/her party NationwideNationwide 83 17 Nationwide IndependentsNationwide Independents 86 14 BattlegroundBattleground 82 18 Battleground BattlegroundIndependents Independents 88 12 4 Across the country, voters agree that they want members of Congress to work together. -

Congressional Report Card

Congressional Report Card NOTE FROM BRIAN DIXON Senior Vice President for Media POPULATION CONNECTION and Government Relations ACTION FUND 2120 L St NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20037 ou’ll notice that this year’s (202) 332–2200 Y Congressional Report Card (800) 767–1956 has a new format. We’ve grouped [email protected] legislators together based on their popconnectaction.org scores. In recent years, it became twitter.com/popconnect apparent that nearly everyone in facebook.com/popconnectaction Congress had either a 100 percent instagram.com/popconnectaction record, or a zero. That’s what you’ll popconnectaction.org/116thCongress see here, with a tiny number of U.S. Capitol switchboard: (202) 224-3121 exceptions in each house. Calling this number will allow you to We’ve also included information connect directly to the offices of your about some of the candidates senators and representative. that we’ve endorsed in this COVER CARTOON year’s election. It’s a small sample of the truly impressive people we’re Nick Anderson editorial cartoon used with supporting. You can find the entire list at popconnectaction.org/2020- the permission of Nick Anderson, the endorsements. Washington Post Writers Group, and the Cartoonist Group. All rights reserved. One of the candidates you’ll read about is Joe Biden, whom we endorsed prior to his naming Sen. Kamala Harris his running mate. They say that BOARD OF DIRECTORS the first important decision a president makes is choosing a vice president, Donna Crane (Secretary) and in his choice of Sen. Harris, Joe Biden struck gold. Carol Ann Kell (Treasurer) Robert K. -

Big Business and Conservative Groups Helped Bolster the Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During the Second Fundraising Quarter of 2021

Big Business And Conservative Groups Helped Bolster The Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During The Second Fundraising Quarter Of 2021 Executive Summary During the 2nd Quarter Of 2021, 25 major PACs tied to corporations, right wing Members of Congress and industry trade associations gave over $1.5 million to members of the Congressional Sedition Caucus, the 147 lawmakers who voted to object to certifying the 2020 presidential election. This includes: • $140,000 Given By The American Crystal Sugar Company PAC To Members Of The Caucus. • $120,000 Given By Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s Majority Committee PAC To Members Of The Caucus • $41,000 Given By The Space Exploration Technologies Corp. PAC – the PAC affiliated with Elon Musk’s SpaceX company. Also among the top PACs are Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and the National Association of Realtors. Duke Energy and Boeing are also on this list despite these entity’s public declarations in January aimed at their customers and shareholders that were pausing all donations for a period of time, including those to members that voted against certifying the election. The leaders, companies and trade groups associated with these PACs should have to answer for their support of lawmakers whose votes that fueled the violence and sedition we saw on January 6. The Sedition Caucus Includes The 147 Lawmakers Who Voted To Object To Certifying The 2020 Presidential Election, Including 8 Senators And 139 Representatives. [The New York Times, 01/07/21] July 2021: Top 25 PACs That Contributed To The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million The Top 25 PACs That Contributed To Members Of The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million During The Second Quarter Of 2021. -

State of Wisconsin

STATE OF WISCONSIN One-Hundred and Third Regular Session 2:06 P.M. TUESDAY, January 3, 2017 The Senate met. State of Wisconsin Wisconsin Elections Commission The Senate was called to order by Senator Roth. November 29, 2016 The Senate stood for the prayer which was offered by Pastor Alvin T. Dupree, Jr. of Family First Ministries in The Honorable, the Senate: Appleton. I am pleased to provide you with a copy of the official The Colors were presented by the VFW Day Post 7591 canvass of the November 8, 2016 General Election vote for Color Guard Unit of Madison, WI. State Senator along with the determination by the Chair of the Wisconsin Elections Commission of the winners. The Senate remained standing and Senator Risser led the Senate in the pledge of allegiance to the flag of the United With this letter, I am delivering the Certificates of Election States of America. and transmittal letters for the winners to you for distribution. The National Anthem was performed by Renaissance If the Elections Commission can provide you with further School for the arts from the Appleton Area School District information or assistance, please contact our office. and Thomas Dubnicka from Lawrence University in Sincerely, Appleton. MICHAEL HAAS Pursuant to Senate Rule 17 (6), the Chief Clerk made the Interim Administrator following entries under the above date. _____________ Senator Fitzgerald, with unanimous consent, asked that the Senate stand informal. Statement of Canvass for _____________ State Senator Remarks of Majority Leader Fitzgerald GENERAL ELECTION, November 8, 2016 “Mister President-Elect, Justice Kelly, Pastor Dupree, Minority Leader Shilling, fellow colleagues, dear family, and I, Michael L. -

Thank You Guide

Great American Outdoors Act: Thank You Guide Phone District 1 Representative Suzan DelBene 202-225-6311 District 2 Representative Rick Larsen 202-225-2605 District 3 Representative Jaime Herrera Beutler 202-225-3536 District 5 Representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers 202-225-2006 District 6 Representative Derek C. Kilmer 202-225-5916 District 7 Representative Pramila Jayapal 202-225-3106 District 8 Representative Kim Schrier 202-225-7761 District 9 Representative Adam Smith 202-225-8901 District 10 Representative Denny Heck 202-225-9740 Senator Maria Cantwell 202-224-3441 Senator Patty Murray 202-224-2621 Email to Co-Sponsors District 1 Suzan DelBene - [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) District 2 Rick Larsen - [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) District 6 Derek C. Kilmer - [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) District 7 Pramila Jayapal - [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) District 8 Kim Schrier - [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) District 9 Adam Smith - [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) District 10 Denny Heck - [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) Senator Maria Cantwell - [email protected] Senator Patty Murray - [email protected] Dear Representative / Senator _____ and [ staff first name ] , My name is _______ and I am a constituent of Washington's [#] Congressional District, as well as a representative of [Organization]. I am reaching out to give a huge thank you for your co-sponsorship and vote in support of the Great American Outdoors Act. -

Lobbying Contribution Report

8/1/2016 LD203 Contribution Report LOBBYING CONTRIBUTION REPORT Clerk of the House of Representatives • Legislative Resource Center • 135 Cannon Building • Washington, DC 20515 Secretary of the Senate • Office of Public Records • 232 Hart Building • Washington, DC 20510 1. FILER TYPE AND NAME 2. IDENTIFICATION NUMBERS Type: House Registrant ID: Organization Lobbyist 35195 Organization Name: Senate Registrant ID: Honeywell International 57453 3. REPORTING PERIOD 4. CONTACT INFORMATION Year: Contact Name: 2016 Ms.Stacey Bernards MidYear (January 1 June 30) Email: YearEnd (July 1 December 31) [email protected] Amendment Phone: 2026622629 Address: 101 CONSTITUTION AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001 USA 5. POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE NAMES Honeywell International Political Action Committee 6. CONTRIBUTIONS No Contributions #1. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,500.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Friends of Sam Johnson Sam Johnson #2. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $2,500.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Kay Granger Campaign Fund Kay Granger #3. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $2,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Paul Cook for Congress Paul Cook https://lda.congress.gov/LC/protected/LCWork/2016/MM/57453DOM.xml?1470093694684 1/75 8/1/2016 LD203 Contribution Report #4. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: DelBene for Congress Suzan DelBene #5. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: John Carter for Congress John Carter #6. -

2012 Political Contributions

2012 POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS 2012 Lilly Political Contributions 2 Public Policy As a biopharmaceutical company that treats serious diseases, Lilly plays an important role in public health and its related policy debates. It is important that our company shapes global public policy debates on issues specific to the people we serve and to our other key stakeholders including shareholders and employees. Our engagement in the political arena helps address the most pressing issues related to ensuring that patients have access to needed medications—leading to improved patient outcomes. Through public policy engagement, we provide a way for all of our locations globally to shape the public policy environment in a manner that supports access to innovative medicines. We engage on issues specific to local business environments (corporate tax, for example). Based on our company’s strategy and the most recent trends in the policy environment, our company has decided to focus on three key areas: innovation, health care delivery, and pricing and reimbursement. More detailed information on key issues can be found in our 2011/12 Corporate Responsibility update: http://www.lilly.com/Documents/Lilly_2011_2012_CRupdate.pdf Through our policy research, development, and stakeholder dialogue activities, Lilly develops positions and advocates on these key issues. U.S. Political Engagement Government actions such as price controls, pharmaceutical manufacturer rebates, and access to Lilly medicines affect our ability to invest in innovation. Lilly has a comprehensive government relations operation to have a voice in the public policymaking process at the federal, state, and local levels. Lilly is committed to participating in the political process as a responsible corporate citizen to help inform the U.S. -

Congress' Power of the Purse

Congress' Power of the Purse Kate Stitht In view of the significance of Congress' power of the purse, it is surprising that there has been so little scholarly exploration of its contours. In this Arti- cle, Professor Stith draws upon constitutional structure, history, and practice to develop a general theory of Congress' appropriationspower. She concludes that the appropriationsclause of the Constitution imposes an obligation upon Congress as well as a limitation upon the executive branch: The Executive may not raise or spend funds not appropriatedby explicit legislative action, and Congress has a constitutional duty to limit the amount and duration of each grant of spending authority. Professor Stith examinesforms of spending authority that are constitutionally troubling, especially gift authority, through which Congress permits federal agencies to receive and spend private contri- butions withoutfurther legislative review. Other types of "backdoor" spending authority, including statutory entitlements and revolving funds, may also be inconsistent with Congress' duty to exercise control over the size and duration of appropriations.Finally, Professor Stith proposes that nonjudicial institu- tions such as the General Accounting Office play a larger role in enforcing and vindicating Congress' power of the purse. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF APPROPRIATIONS 1346 A. The Constitutional Prerequisitesfor Federal Gov- ernment Activity 1346 B. The Place of Congress' Power To Appropriate in the Structure of the Constitution 1348 C. The Constitutional Function of "Appropriations" 1352 D. The Principlesof the Public Fisc and of Appropria- tions Control 1356 E. The Power to Deny Appropriations 1360 II. APPROPRIATIONS CONTROL: THE LEGISLATIVE FRAME- WORK 1363 t Associate Professor of Law, Yale Law School. -

Union Calendar No. 53

Union Calendar No. 53 117TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 1st Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 117–78 R E P O R T ON THE SUBALLOCATION OF BUDGET ALLOCATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2022 SUBMITTED BY MS. DELAURO, CHAIR, COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS together with MINORITY VIEWS JULY 1, 2021.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 19–006 WASHINGTON : 2021 SBDV 2022–2 VerDate Sep 11 2014 01:59 Jul 06, 2021 Jkt 019006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR078.XXX HR078 rfrederick on DSKBCBPHB2PROD with HEARING E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS ROSA L. DELAURO, Connecticut, Chair MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio KAY GRANGER, Texas DAVID E. PRICE, North Carolina HAROLD ROGERS, Kentucky LUCILLE ROYBAL-ALLARD, California ROBERT B. ADERHOLT, Alabama SANFORD D. BISHOP, JR., Georgia MICHAEL K. SIMPSON, Idaho BARBARA LEE, California JOHN R. CARTER, Texas BETTY MCCOLLUM, Minnesota KEN CALVERT, California TIM RYAN, Ohio TOM COLE, Oklahoma C. A. DUTCH RUPPERSBERGER, Maryland MARIO DIAZ-BALART, Florida DEBBIE WASSERMAN SCHULTZ, Florida STEVE WOMACK, Arkansas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska CHELLIE PINGREE, Maine CHUCK FLEISCHMANN, Tennessee MIKE QUIGLEY, Illinois JAIME HERRERA BEUTLER, Washington DEREK KILMER, Washington DAVID P. JOYCE, Ohio MATT CARTWRIGHT, Pennsylvania ANDY HARRIS, Maryland GRACE MENG, New York MARK E. AMODEI, Nevada MARK POCAN, Wisconsin CHRIS STEWART, Utah KATHERINE M. CLARK, Massachusetts STEVEN M. PALAZZO, Mississippi PETE AGUILAR, California DAVID G. VALADAO, California LOIS FRANKEL, Florida DAN NEWHOUSE, Washington CHERI BUSTOS, Illinois JOHN R. MOOLENAAR, Michigan BONNIE WATSON COLEMAN, New Jersey JOHN H. -

2018 Annual Report | 1 “From the U.S

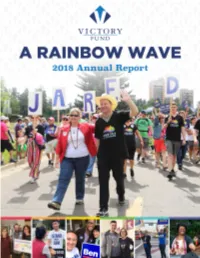

A Rainbow Wave: 2018 Annual Report | 1 “From the U.S. Congress to statewide offices to state legislatures and city councils, on Election Night we made historic inroads and grew our political power in ways unimaginable even a few years ago.” MAYOR ANNISE PARKER, PRESIDENT & CEO LGBTQ VICTORY FUND BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chris Abele, Chair Michael Grover Richard Holt, Vice Chair Kim Hoover Mattheus Stephens, Secretary Chrys Lemon Campbell Spencer, Treasurer Stephen Macias Stuart Appelbaum Christopher Massicotte (ex-officio) Susan Atkins Daniel Penchina Sue Burnside (ex-officio) Vince Pryor Sharon Callahan-Miller Wade Rakes Pia Carusone ONE VICTORY BOARD OF DIRECTORS LGBTQ VICTORY FUND CAMPAIGN BOARD LEADERSHIP Richard Holt, Chair Chris Abele, Vice Chair Sue Burnside, Co-Chair John Tedstrom, Vice Chair Chris Massicotte, Co-Chair Claire Lucas, Treasurer Jim Schmidt, Endorsement Chair Campbell Spencer, Secretary John Arrowood LGBTQ VICTORY FUND STAFF Mayor Annise Parker, President & CEO Sarah LeDonne, Digital Marketing Manager Andre Adeyemi, Executive Assistant / Board Liaison Tim Meinke, Senior Director of Major Gifts Geoffrey Bell, Political Manager Sean Meloy, Senior Political Director Robert Byrne, Digital Communications Manager Courtney Mott, Victory Campaign Board Director Katie Creehan, Director of Operations Aaron Samulcek, Chief Operations Officer Dan Gugliuzza, Data Manager Bryant Sanders, Corporate and Foundation Gifts Manager Emily Hammell, Events Manager Seth Schermer, Vice President of Development Elliot Imse, Senior Director of Communications Cesar Toledo, Political Associate 1 | A Rainbow Wave: 2018 Annual Report Friend, As the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising approaches this June, I am reminded that every so often—perhaps just two or three times a decade—our movement takes an extraordinary leap forward in its march toward equality. -

Employees of Northrop Grumman Political Action Committee (ENGPAC) 2017 Contributions

Employees of Northrop Grumman Political Action Committee (ENGPAC) 2017 Contributions Name Candidate Office Total ALABAMA $69,000 American Security PAC Rep. Michael Dennis Rogers (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Byrne for Congress Rep. Bradley Roberts Byrne (R) Congressional District 01 $5,000 BYRNE PAC Rep. Bradley Roberts Byrne (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Defend America PAC Sen. Richard Craig Shelby (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Martha Roby for Congress Rep. Martha Roby (R) Congressional District 02 $10,000 Mike Rogers for Congress Rep. Michael Dennis Rogers (R) Congressional District 03 $6,500 MoBrooksForCongress.Com Rep. Morris Jackson Brooks, Jr. (R) Congressional District 05 $5,000 Reaching for a Brighter America PAC Rep. Robert Brown Aderholt (R) Leadership PAC $2,500 Robert Aderholt for Congress Rep. Robert Brown Aderholt (R) Congressional District 04 $7,500 Strange for Senate Sen. Luther Strange (R) United States Senate $15,000 Terri Sewell for Congress Rep. Terri Andrea Sewell (D) Congressional District 07 $2,500 ALASKA $14,000 Sullivan For US Senate Sen. Daniel Scott Sullivan (R) United States Senate $5,000 Denali Leadership PAC Sen. Lisa Ann Murkowski (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 True North PAC Sen. Daniel Scott Sullivan (R) Leadership PAC $4,000 ARIZONA $29,000 Committee To Re-Elect Trent Franks To Congress Rep. Trent Franks (R) Congressional District 08 $4,500 Country First Political Action Committee Inc. Sen. John Sidney McCain, III (R) Leadership PAC $3,500 (COUNTRY FIRST PAC) Gallego for Arizona Rep. Ruben M. Gallego (D) Congressional District 07 $5,000 McSally for Congress Rep. Martha Elizabeth McSally (R) Congressional District 02 $10,000 Sinema for Arizona Rep.