C H a P T E R -III S O C Io

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Geographical Study of Child Sex Ratio in Ahmednagar District (MS)

International Journal of Applied Research 2015; 1(12): 49-52 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 A geographical study of child sex ratio in Ahmednagar IJAR 2015; 1(12): 49-52 www.allresearchjournal.com district (MS) Received: 09-09-2015 Accepted: 10-10-2015 Shailesh M Nikam Shailesh M Nikam Prof. Dept. of Geography, Abstract Pemraj Sarda College, Ahmednagar. The child sex ratio in Ahmednagar district was 852 as per 2011 census. Out of fourteen tahsils only in five tehsil have more than district’s average CSR but remaining ten tehsil have below district’s CSR. Out of 1462 villages in this taluka the child sex ratio (CSR) was found below 600 in 28 villages, the CSR found between 600 - 700 in 63 villages, in 237 villages the CSR was found between 700 – 800, while in the 468 villages the CSR was lies between 800 - 900 and above 900 CSR found in 666 villages in Ahmednagar district. Near about 55% villages have below 900 child sex ratio. Keywords: CSR, villages, boys, girls. Introduction There are various elements of population composition. Among these elements sex composition is important compassion and holds a prime place for social point of view. The balance between two sexes affects the social and economic relationship within a community. The profound effect of the proportion of the two sexes upon the other demographic elements like population growth, marriage rates, occupational structure etc. Therefore, bthe bstudy of sex ratio is very important. Objectives 1) To examine the child sex ratio in Ahmednagar district. -

Integrated Village Development

CHAPTER 11 Integrated Village Development Introduction Table 11.1: Size-Distribution of Villages in The saying, "India lives in its villages" is relevant Maharashtra, 1991 even today, in the new millennium. Like India, Population size No. of villages Maharashtra too, has a large number of villages and Less than 200 3461 (8.56) a substantial proportion of its population living in 200-499 8242 (20.39) the rural areas. About 58 per cent of the total 500-999 12,408 (30.70) population of the state lives in 43,722 villages; thus 1000-1999 10,632 (26.31) the rural areas need provision of adequate 2000-4999 4,715 (11.67) infrastructure to ensure a decent quality of life. Village life in the state is governed by dependency 5000-9999 762 (1.89) on agriculture, which in turn is plagued by the 10,000 & above 192 (0.47) problem of low yields and low irrigated acreage, Total 40,412 (100) which further compounds the developmental Note: Values in brackets are percentage to total. problem. To ensure the development of villages, it Source: GoM (1996): Statistical Abstract of Maharashtra State, Part I, 1991-92 and 1992-93 is necessary to address the problem of introducing modern methods in agriculture, provision for Rural Population identification of alternative sources of employment, provision of quality health facilities, education The proportion of rural population of the state has facilities, communication facilities, power supply fallen from 72 per cent of total population in 1961 and finally building up village institutions to to 58 per cent in 2001. -

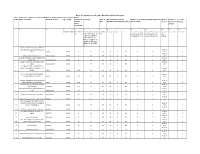

Bpc(Maharashtra) (Times of India).Xlsx

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships BPCL proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Maharashtra as per following details : Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Estimated Category Type of Minimum Dimension (in Finance to be arranged by the applicant Mode of Fixed Fee / Security monthly Site* M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. M.). * (Rs in Lakhs) Selection Minimum Bid Deposit Sales amount Potential # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Regular / Rural MS+HSD in SC/ SC CC1/ SC CC- CC/DC/C Frontage Depth Area Estimated working Estimated fund required Draw of Rs in Lakhs Rs in Lakhs Kls 2/ SC PH/ ST/ ST CC- FS capital requirement for development of Lots / 1/ ST CC-2/ ST PH/ for operation of RO infrastructure at RO Bidding OBC/ OBC CC-1/ OBC CC-2/ OBC PH/ OPEN/ OPEN CC-1/ OPEN CC-2/ OPEN PH From Aastha Hospital to Jalna APMC on New Mondha road, within Municipal Draw of 1 Limits JALNA RURAL 33 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 2 VIllage jamgaon taluka parner AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE KOMBHALI,TALUKA KARJAT(NOT Draw of 3 ON NH/SH) AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Ambhai, Tal - Sillod Other than Draw of 4 NH/SH AURANGABAD RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON MAHALUNGE - NANDE ROAD, MAHALUNGE GRAM PANCHYAT, TAL: Draw of 5 MULSHI PUNE RURAL 300 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON 1.1 NEW DP ROAD (30 M WIDE), Draw of 6 VILLAGE: DEHU, TAL: HAVELI PUNE RURAL 140 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE- RAJEGAON, TALUKA: DAUND Draw of 7 ON BHIGWAN-MALTHAN -

Why Untouchability, Caste Discrimination and Atrocities Still Persists Despite Law? Reflections on Causes for Persistence and Solutions”

9th Dr. Asghar Ali Engineer Memorial Lecture on “Why Untouchability, Caste Discrimination and Atrocities still persists despite Law? Reflections on Causes for Persistence and Solutions” by Prof. Sukhdeo Thorat (Padma Shri Sukhadeo Thorat is an economist and was the former Chairman of the University Grants Commission and Indian Council of Social Science and Research.) Date: 5th August 2017 Venue: The Asiatic Society of Mumbai, Durbar Hall, Shahid Bhagat Singh Road, Fort, Mumbai: - 400023. Centre for Study of Society and Secularism 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Prabhat Colony Road, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 55 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] www.csss-isla.com 1 Why Untouchability and Atrocities Persist Despite Laws?: What government should do to reduce untouchability and atrocities in the villages in Maharashtra? Sukhadeo Thorat Shri Dinesh Waghmare, Secretary, Ministry of Social Justice and Special Assistance, Government of Maharashtra, Shri Irfan Engineer, Director, Centre for Study of Society and Secularism and Ladies and Gentlemen I am grateful to Shri Irfan Engineer for inviting me to deliver the Dr Asghar Ali Engineer Memorial Lecture. It is indeed an honour to commemorate the services rendered by Dr Asghar Ali Engineer in promotion of human right and for the secular character of India, as also to the cause of religious and social minorities such as the Muslims and the Dalits. It is an opportunity for me and to all of us to recall his contribution and draw inspiration to take the cause further. On this occasion, I thought it would be appropriate time to discuss the issue of human rights with regard to the Dalits of Maharashtra, something that has recently emerged quite prominently in public domain. -

Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Dairy Farming of Ahmednagar District

SPATIO-TEMPORAL ANALYSIS OF DAIRY FARMING OF AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT A Thesis submitted to Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) In GEOGRAPHY Under the Board of Moral and Social Sciences By Shri SANJAY D. AGHAV Under the Guidance of Dr. HEMANT M. PEDNEKAR Principal,Sonopant Dandekar College. Palghar,Dist.Palghar. November - 2017 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation entitled “SPATIO-TEMPORAL ANALYSIS OF DAIRY FARMING OF AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT” is being submitted herewith for the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in Geography of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Shri. Sanjay Dhondiba Aghav under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any degree or similar title of this or any other university or examining body. Research Guide Dr. Hemant M. Pednekar Place: Pune Date: 09/11/2017 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled SPATIO-TEMPORAL ANALYSIS OF DAIRY FARMING OF AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT completed and written by me has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree or other similar title of this or any other University or examining body. Research Student Place: Pune Shri. Sanjay Dhondiba Aghav Date: 09/11/2017 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There are many people who helped me in successful completion of this research work. I have had the benefit of guidance by Dr. Hemant Pednekar, my guide, who carefully read each and every line of this thesis and his valuable criticism helped me a good deal in putting my thoughts into the form in which they are presented now. -

Chapter 7 Problems of Agriculture and Agro

CHAPTER 7 PROBLEMS OF AGRICULTURE AND AGRO-BASED INDUSTRIES 7.1 Introduction The previous chapter gives details of agro-based industries existed in the Ahmednagar district during the decade 1981-90. Chapter 4 gives d e ta ils of agro-produce of the d is t r ic t . I t is found that, both ag ric u ltu re as well as agro-based industries had no speedy progress in the district during the decade. This chapter emphasises some of the problems of a g ric u ltu re and agro-based industries in Ahmed nagar d is t r ic t . 7.2 TalukaMise irrigation sources and imbalance in net irrigated area in the district There are 13 talukas in the Ahmednagar district, some of them were irrig a te d , whereas some were dry. Ir r ig a tio n was unequal in the d is t r ic t during the decade 1981-90. This imbalance in irrigation created imbalance in agricultural development. Water is also the basic need for industrialisa tion, but there was scarcity of water even for drinking in Pathardi, Shevgaon, Jamkhed, Parner and Karjat talukas. Agro-industrialisation was very slow in these talukas due to non availability of water supply. Inadequate water supply affects the production of agro-based industries, for exam ple, paper mill of Sangamner sugar factory was facing a 241 severe problem of water supply during the year 1986-87, which affected the production of th is m ill.^ There are two types of irrigation. One is well irriga tion and the other is surface irrigation. -

Profile of Ahmednagar District Contents

e H A P T E R THREE Profile of Ahmednagar District Contents 3.1 PHYSICAL SETTING 3.1.1 LOCATION 3.1.2 AREA 3.1.3 BOUNDARIES ( 3.1.4 RIVERS 3.1.5 CLIMATE 3.1.6 RAINFALL 3.2 POPULATION AND OCCUPATIONAL PATTERN 3.2.1 POPULATION OF THE AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT. 3.2.2 OCCUPATIONAL PATTERN 3.3 AGRICULTURE 3.3.1 DISTRIBUTION OF LAND HOLDING 3.3.2 LAND USE 3.3.3 CROPPING PATTERN 3.3.4 TALUKAWISE CULTIVABLE LAND AND AREA UNDER IRRIGATION. 3.4 FOREST 3.5 ROAD CONSTRUCTION WORKS UNDER E. G. S. , P.W.D. , &.Z.P. 3 .6 NO. OF CIVIL CONTRACTORS 3.7 MARKET COMMITTEES cxmtCvuyie'.. 3.8 LIVE STOCK 3.8.1 LIVE STOCK POPULATION 3.8.2 VETERINARY FACILITIES 3.9 PUBLIC & GOVT. AIDED FINANCIAL AIDED MEDICAL FACILITIES 3 .1 0 BDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS 3.11 CO-OPERATIVE MOVEMENT IN AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT 3.12 INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT IN AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT. 3.13 TRANSPORT & COMMUNICATION 39 CHAPTER III. PROFILE OF AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT Brief History of Ahmednagar is named after Ahmednagar town. The town is famous since the medieval times. In the year 1490 when Ahmed, Nizam, Shah, the founder of the Nizam dynasty defeated the Bahamani troops under Jahagir Khan near its site. This victory was called the “Victory of the Garden”. Because on that spot Ahmed Shah built a palace and laid out a garden. In the year 1494 he laid the foundation of the city close to the Bag Nizam upon the left bank of the Sina river and called after himself Ahmednagar or the city of Ahmed. -

9960702639 ªÉ¶É´Éæié Ëjé¤Éeò Eò

महाराष्ट्र रा煍यातील नⴂदणीकृ त र्ते करी उत्पादक कं पनयांची यादी List of Registered Farmer Producer Companies in Maharashtra State Month of December 2018 DATE OF S.No CIN COMPANY_NAME REGISTERED_OFFICE_ADDRESS EMAIL Contact Person Contact No REGISTRATION Ahmednagar 135 H. NO. 671/A, RASHIN TAL- KARJAT AAISAHEB AGRO PRODUCER kamble.santosh2201@gmail. 1 U01114PN2017PTC173196 30-10-2017 AHMEDNAGAR Ahmednagar MH 414403 COMPANY LIMITED com संजय जाधव ९६६५६५३३९३ IN ADARSH SAI MAULI GUT NO HOUSE NO 6 DAHEGAON MÉÉä®úIÉxÉÉlÉ ÊºÉiÉÉ®úÉ¨É 9657752257/ 2 U01400PN2015PTC153935 PRODUCER COMPANY 03-02-2015 BOLKA KOPARGAON Maharashtra [email protected] LIMITED INDIA 423603 ®úÉʶÉxÉEò®ú 9960702639 ADARSHA GRAMEEN AGRO PIMPRI LAUKI AJAMAPUR, TAL - SANGAMNER, DIST - 3 U01403PN2014PTC152109 PRODUCER COMPANY 08-08-2014 [email protected] दिलीप लवारे ९९२२६२०८१३ AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER LIMITED Maharashtra INDIA 422605 GAT. NO. 213, AGADGAON, TAL- AGADGAON KALBHAIRAVNATH NAGAR, DIST. AHMEDNAGAR, 4 U01113PN2018PTC177495 FARMERS PRODUCERCOMPANY 02-07-2018 [email protected] ªÉ¶É´ÉÆiÉ ËjɤÉEò Eò®úɳäý AGADGAON AHMEDNAGAR Ahmednagar - LIMITED MH 414001 IN AT-POST- MEHENDURI, TALUKA- [email protected], AGASTI FARMERS PRODUCER 9359171653/ 5 U01400PN2015PTC154186 02-03-2015 AKOLE, DIST-AHMEDNAGAR, agastifarmersproducerco@g ववकास देवराम COMPANY LIMITED AKOLE Maharashtra INDIA 422601 mail.com आरोटे 9975299214 AGROVISION FARMERS Ahmednagar Bazar, Awar, Chahurana Bk., T.P. Scheme No.3, Kadba Building, 6 U15122PN2013PTC149254 PRODUCER COMPANY 24-10-2013 [email protected] 1st Floor, Block No.2 Ahmednagar +Êxɯûvnù ½þ®úÒ ¨ÉÉä®äú - LIMITED Maharashtra INDIA 414001 AHMEDNAGAR DAIRY FARMERS Bhenda Khurd, Tal- Newasa 7 U01100PN2017PTC168014 18-01-2017 PRODUCER COMPANY LIMITED Ahmednagar Ahmednagar MH 414603 IN HOUSE NO. -

NARI 2015 Annual Report

1 ANNUAL RESEARCH REPORT 2014-2015 Nimbkar Agricultural Research Institute, NARI P.O. Box 44, PHALTAN-415523, Maharashtra September 2015 2 Nimbkar Agricultural Research Institute (NARI), Phaltan ANNUAL RESEARCH REPORT 2014-15 Report of the President I am very happy to place the annual research report 2014-15 of NARI before our readers. Significant research progress at NARI has been presented in brief. For more details of any subject, readers are encouraged to visit our website and/or write an e-mail to us. Some of the highlights of the year were as follows : 1. Dr. Anil K. Rajvanshi received the distinguished alumnus award from the University of Florida (UF) in Gainesville (USA). It was given on the third of May 2014 during the summer commencement ceremonies. Dr. Rajvanshi also gave a short address at the commencement after receiving the award. Dr. Rajvanshi is the first Indian to be given this award by UF. 2. Shri. Rajesh Aggarwal, Principal Secretary, Department of Information Technology, Maharashtra commissioned the new custom-built buck and ram semen freezing laboratory in the presence of NARI‟s founder Shri. B. V. Nimbkar and about 100 invitees. 3. Dr. Anil K. Rajvanshi‟s e-book “Romance of innovation-A human interest story of doing R&D in rural setting”, was released in Pune on 20 October 2014 by Padma Vibhushan Dr. R. A. Mashelkar and Dr. Rajat Moona, Director General of CDAC in a well-attended function. This book has been made freely available on the internet in the fond hope that it may inspire the young researchers to be engaged in rural development. -

22Selectlist.Pdf

MAHARASHTRA STATE COUNCIL OF EXAMINATIONS, PUNE NATIONAL MEANS CUM MERIT SCHOLARSHIP SCHEME EXAM 2013-14 ( STD - 8 th ) SELECTION LIST DISTRICT : 22 AHMEDNAGAR Date : 10/06/2014 Page : 1 of 37 CATEGORY : GENERAL Sr. School School Name Birth Caste Disablility MAT SAT TOTAL Remark Seat No. Name of Candidate Gender No. Code Date Category Status Marks Marks MARKS 1 339142206111 CHEDE ABHISHEK MAHADEV 2209445 OM GURUDEV MADHYAMIK GURUKUL KOKAMTHAN PO JEUR KUMBHARI 5/10/2000 MaleGeneral None 81 81 162 GEN - 001 TAL KOPARGAON DIST AHMEDNAGAR, KOPARGAON 2 339142208036 BORUL GAYATRI SACHIN 2213003 ABASAHEB KAKDE VIDYALAYA SHEVGAON MIRI ROAD SHEVGAON 5/28/2000 FemaleOBC None 84 77 161 GEN - 002 TAL-SHEVGAON, SHEVGAON 3 339142204065 HASE AISHWARYA YADHAVRAO 2202002 B.G.P. SAHYDRI VIDYALAYA SANGAMNER NEAR GUEST HOUSE, 6/11/2000 FemaleGeneral None 88 72 160 GEN - 003 NASHIK-PUNE HIGHWAY, SANGAMNER, TAL-SANGAMNER, DIST-AHMADNAGAR 422605, SANGAMNER 4 339142203235 PUJARI HARSHAL SUNIL 2210019 KESHAV GOVIND VIDYALAYA, BELAPUR (KH) A/P BELAPUR KD TAL 1/11/2001 MaleGeneral None 68 78 146 GEN - 004 SHRIRAMPUR DIST AHMEDNAGAR, SHRIRAMPUR 5 339142206113 KURE SAURABH KUSHEBRAO 2209445 OM GURUDEV MADHYAMIK GURUKUL KOKAMTHAN PO JEUR KUMBHARI 7/6/2000 MaleGeneral None 70 75 145 GEN - 005 TAL KOPARGAON DIST AHMEDNAGAR, KOPARGAON 6 339142203109 LONDHE RAJ RAMESH 2210018 J. T. S. HIGH SCHOOL, BELAPUR AP BELAPUR, TAL SHRIRAMPUR, DIST 11/10/2000 MaleGeneral None 65 80 145 GEN - 006 AHMEDNAGAR, SHRIRAMPUR 7 339142215070 DHUS KAUSTUBH ANANT 2206005 SHRI CHATRAPATI SHIVAJI MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA DEOLAILI PRAVARA 7/31/2000 MaleGeneral None 73 70 143 GEN - 007 A/P DEOLALI PRAVARA, TAL. -

STAMP DUTY EXEMPTION No

DIS List of the units - STAMP DUTY EXEMPTION No. Name & Address of the unit Regn.No.&Date Purpose Date of issue Taluka Status 1 Beton Concrete Products Pvt. 11.01.14127 For Purchase of Land 20.09.2001 Newasa Ltd.G.No.223,Khadka,Tal-Newasa 03.03.2001 W 2 Tirupati Industries, Plot No.116/2, 11.01.11775 Deed For MIDC Plot 05.10.2001 Parner [MIDC] MIDC Supa , Tal-Parner 22.10.1999 Under construction 3 Sai Photo Colour Lab.,Gala 11.01.00671 For Purchase Shop 04.12.2001 Jamkhed No.7,Kharedi Vikri Sangh 20.01.2001 Complex, Tal-Jamkhed W 4 Bhagwandas Tyres,G.No.704, 11.01.12980 Hypothecation for Loan 10.12.2001 Newasa Ghodegaon,Tal-Newas 17.03.2001 W 5 Pacific Industries,Plot No.A- 11.01.15007 Deed For MIDC Plot 12.12.2001 Shrirampur 123MIDC,Shrirampur 27.08.2001 [MIDC] 6 Shreyasnath Sand 11.01.12958 Hypothecation for Loan 26.12.2001 Shrigonda CrusherG.No.854/1/1,Deodeithan, 03.03.2001 Tq-Shrogonda Closed 7 Siddhivinayak Agro Pvt.Ltd.,Gat 11.01.13015 Hypothecation for Loan 26.12.2001 Parner No.427,Nighoj,Tq-Parner 27.03.2001 Closed 8 Amco-Nilco India,B-41,B-42,Supa 11.01.14478 Deed For MIDC Plot 31.01.2002 Parner MIDC,Tal-Parner 24.01.2002 [MIDC] 9 Vishal InternationalB-8 Supa 11.01.14698 Deed For MIDC Plot 18.04.2002 Parner MIDC,Tq-Parner 30.03.2002 [MIDC] 10 Vishal International[Unit-A]B-6 11.01.14730 Deed For MIDC Plot 18.04.2002 Parner Supa MIDC,Tq-Parner 09.04.2002 [MIDC] Under construction 11 Vishal International[Unit-B]D-84, 11.01.14733 Deed For MIDC Plot 18.04.2002 Parner Supa MIDC, Tq – Parner 09.04.2002 Reinvesti Supa MIDC, Tq Parner -

Spatial Analysis of Agricultural Landuse in Ahmednagar District in 2010-11

© IJEDR 2018 | Volume 6, Issue 4 | ISSN: 2321-9939 Spatial Analysis Of Agricultural Landuse In Ahmednagar District In 2010-11 Prof. Erande Manohar Ramnath, Dr. Khakre Rajeshwar D. Assistant Professor Shri Mulikadevi College Nighoj, Tal. Parner, Dist. Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India. 414306 Jaikranti College Latur, Tal. Dist. Latur ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract - The net sown area, current fallows and land under tree crops and groves are included in agricultural land use. Use of land is an important factor for planning process because of the predetermined nature of land resource. In Ahmednagar district covered an area of about three-fifth area under plough in Kharif (62 percent to net sown area) and less than two-fifth was under Rabi (38 percent to net sown area) season in the district. The crops viz. Bajra, Rice, Cotton, Wheat, Jawar, Maize, Vegetable, Pulses, Fodder crops, Oilseeds, Sugarcane and Fruits were cultivated in the district. Jawar is leading crop in Ahmednagar District. The Percentage of Jawar is 25.31 percent, Bajara is 19.29 percent, Sugarcane is 6.90 percent, Pulses is 5.37 percent, Wheat is 5.29 percent, Fodder crops are 4.90 percent, Oilseeds are 4.68 percent, Cotton is 4.63 percent, Vegetables are 3.46 percent, Fruits are 1.41 percent, Maize is 1.16 percent, Rice is 0.77 and Other crops are 0.76 percent recorded. Percentage area under cultivation of bajara, oilseeds, Jawar, pulses, wheat and rice was found to be decreased, while percentage area of vegetable, fodder, fruits and sugarcane was found to be increased. Key Words - Crop, Spatial analysis, Agricultural Landuse.