Towards a Deeper Understanding of Store Branded Lookalikes: Similarity Judgment and Price Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

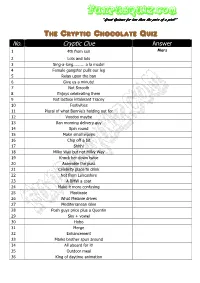

FPQ Jubilee Chocolate Quiz

FUNPUBQUIZ. Com “““GGGreatGreat Quizzes for less than the price of a pint!˝ The Cryptic Chocolate Quiz No. Cryptic Clue Answer 1 4th from sun Mars 2 Lots and lots 3 Sing-a-long......... a la mode! 4 Female gangster pulls our leg 5 Relax upon the ban 6 Give us a minute! 7 Not Smooth 8 Enjoys celebrating them 9 Not lactose intolerant Tracey 10 Festivities 11 Plural of what Bonnie's holding out for 12 Voodoo maybe 13 Ban morning delivery guy 14 Spin round 15 Make small waves 16 Chip off a bit 17 Shhh! 18 Milky Way but not Milky Way 19 Knock her down twice 20 Assemble the puss 21 Celebrity place to drink 22 Not from Lancashire 23 A BMW a coat 24 Make it more confusing 25 Masticate 26 What Melanie drives 27 Mediterranean Glee 28 Posh guys price plus a Quentin 29 Sky + vowel 30 Hobo 31 Merge 32 Enhancement 33 Marks brother spun around 34 All aboard for it! 35 Outdoor meal 36 King of daytime animation FUNPUBQUIZ. Com “““GGGreatGreat Quizzes for less than the price of a pint!˝ 37 Pants start with a constanant 38 Twisted noel 39 Subject 40 Out on his own cowboy 41 Planets not hatched 42 Confectionary network 43 Direction not near 44 Scruff up the hair 45 Use the oar to unlock the door 46 Opposite to merge 47 Flightless bird 48 Caveman's weapon is in superb condition 49 Vixen's timeless 50 Cab! 51 Those and those 52 Small meal 53 Ageing Caribbean isle 54 Only the best live here 55 The same the other way around 56 Clever ones 57 Romantic flowers 58 No credit here just... -

Washington, Saturday, November 17, 1951

♦ VOLUME 16 ■ NUMBER 224 Washington, Saturday, November 17, 1951 TITLE 3— THE PRESIDENT (b) Share tenant and share cropper CONTENTS protection. Notwithstanding the estab EXECUTIVE ORDER 10305 lishment of a proportionate share for THE PRESIDENT each farm under paragraph (a) of this Revoking E xecutive O rder No. 102071 op section, eligibility of any producer of Executive Order , PaSe January 23, 1951, E stablishing the sugarcane for payment shall be subject Revocation of E. O. No. 10207 es President’s C om m ission on I nternal to the following conditions: tablishing President’s Commis Security and I ndividual R ights (1) That the number of share tenants sion on Internal Security and By virtue of the authority vested iif me or share croppers engaged in the produc Individual Rights____________ » 11667 as President of the United States, it is tion of sugarcane of the 1951-52 crop on EXECUTIVE AGENCIES ordered as follows: the farm shall not be reduced below the 1. Executive Order No. 10207 of Janu number so engaged with respect to the Agriculture Department ary 23, 1951, entitled “Establishing the previous crop, unless such reduction is See Production and Marketing President’s Commission on Internal Se approved by the Director of the Carib Administration. curity and Individual Rights’’, is hereby bean Area Office of the Production and Civil Aeronautics Administra revoked. Marketing Administration, San Juan, tion 2. The Department of the Treasury Puerto Rico; and Proposed rule making: shall liquidate the outstanding affairs of (2) That such producer shall not have Airworthiness certificates_____11697 the said Commission, and unexpended entered into any leasing or cropping Certification and operation rules funds of the Commission shall be avail agreement for the purpose of diverting to for scheduled air carriers op able for the purposes of such liquidation. -

Nielsen FMCG 2019 Brand by Category List

FUSION 2020 TECHNICAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2020 __________________________________________________________________________ 13. NIELSEN FMCG CATEGORY AND BRAND LIST - ALPHABETIC BY BRAND Brand Category Brand Category 123 Household Cleaners ALWAYS Sanitary Pads and Panty Liners 11 O`CLOCK Tea ALZU Eggs 5 STAR Chocolate Coated Line AMERICAN PARLOUR Ice Cream 8.AM Cereals - Ready To Eat AMILA Iced Tea A PLUS Sugar AMILA Powdered So Drinks ACE Cereals - Ready To Eat AMINAS Meal Soluons ACE Coffee - Ground / Beans ANADIN Analgesics ACE Maize Meal ANAMAFUTHA Maas ACE Maize Ready to Eat ANCHOR Yeast ACE Samp ANGEL Petroleum Jelly ADCO Analgesics ANGEL Toilet Paper ADCODOL Analgesics ANGIE Bath Addives ADIDAS Deodorants ANTIGUA Milk Modifiers (Hot) AERO Chocolate Coated Line APOLLO Chilled Processed Meats AERO Moulded Slab / Bar Chocolate APPLETISER Fruit Juice - Long Life AERO SOFT Toilet Paper AQUAFRESH Mouth Wash AIROMA Air Fresheners AQUAFRESH 4 Toothbrushes AIRWICK Air Fresheners AQUAFRESH 4 Toothpaste ALBANY Bread AQUAMARINE Condioners - Rinse Off ALBEX Bleach AQUAMARINE Shampoo ALBEX Sanitary Cleaners AQUARTZ Mineral Water ALCOPHYLLEX Cold & Flu Remedies AQUELLE Mineral Water ALEO Fruit Juice - Long Life ARIEL Heavy Duty Detergents ALFER FARMS Eggs ARMSTRONG Eggs Maize Drink (Fermented Non ALL GOLD Canned Tomatoes ASEMZANSI Alcoholic) ALL GOLD Fruit Juice - Long Life ASTRA Laundry Bar Soap ALL GOLD Mustard ASTROS Chocolate Coated Line ALL GOLD Sauces - Table AUNT CARO-LINE Rice ALL GOLD Sauces - Tomato AUNT SALLY Vinegar ALL GOLD Spreads - Jam -

General Corporation Tax (GCT)

CITY OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE 1998 - STOCK ALLOCATION BELOW 100 PERCENT REPORT NAME ISSUERS ALLOCATION PERCENT NAME ISSUERS ALLOCATION PERCENT #78 GIAC LEASING CORPORATION 1.33 A F FIRE PROTECTION CO INC 13.54 "K" LINE AIR SERVICE (U.S.A.) 23.80 A F LEWIS & CO OF NEW YORK 23.20 A B DISTRIBUTORS INC 92.94 A F SUPPLY CORP 82.38 A L SHET METAL FABRICATIONS 69.80 A FEIBUSCH CORP 83.30 A & B AGENCY 25.00 A FINE GAUGE INC 59.27 A & C MECHANICAL INC LONG IS 0.44 A FOSTER HIGGINS INC 16.05 A & D ENTERPRISES, INC 75.45 A G EDWARDS SONS INC 1.45 A & D MECHANICAL INC 65.57 A G H TRIMSOURCE INC 76.57 A & E BUSINESS ADVISORS INC 67.80 A G INTERNATIONAL INC 17.20 A & E DENTAL STUDIO INC 89.20 A G INTERTAINMENT 7.67 A & E MANAGEMENT SYST 2.00 A H ENGINEERS PC 97.22 A & F INSTALLATIONS INC 10.19 A H HARRIS SONS INC 0.17 A & J FIXTURES INC 10.20 A H SCHREIBER CO INC 24.04 A & J FIXTURES, INC. 5.81 A H SPORTSWEAR CO INC 69.19 A & J HEATING & AIR CONDITIONISERVICE 62.50 A H VIDEO SALES REPRESENTIVE 59.56 A & M BILLING CONSULTANTS INC 17.30 A HARTRODT VIA INC 63.60 A & M BRONX BAKING INC 24.95 A HELLER METALS CO INC 90.88 A & N DELIVERY SERVICE, INC. 10.09 A I & ASSOCIATES INC 5.08 A & R DEVELOPMENT INC 45.42 A I PROFESSIONAL CLEANING 88.00 A & R RECYCLING INC. -

8. Fusion Category and Brand Lists – Alphabetic by Brand

PAMS 2017 TECHNICAL REPORT APRIL 2018 8. FUSION CATEGORY AND BRAND LISTS – ALPHABETIC BY BRAND Brand Category Brand Category 123 Household Cleaners ALETTES Biscuits 11 O`CLOCK Tea ALFER FARMS Eggs 24 SEVEN Deodorants ALHAMI Pasta - Convenience 5 STAR Chocolate Coated Line ALKA FIZZ Stomach Remedies 7 STARS Sports & Energy Drinks ALL GOLD Canned Tomatoes 7 UP CSDs ALL GOLD Canned Vegetables A VOGEL Herbs / Spices ALL GOLD Fruit Juice - Long Life A1 Pasta ALL GOLD Mayonnaise ACE Cereals - Ready To Eat ALL GOLD Mustard ACE Coffee - Ground / Beans ALL GOLD Sauces - Tomato ACE Coffee - Total ALL GOLD Sauces - Wet Pasta ACE Food Wrap / Bags ALL GOLD Soup - Canned ACE Maize (Ready To Eat) ALL GOLD Spreads - Jam ACE Maize Meal ALL IN ONE Chocolate Coated Line ACE Samp ALL JOY Mustard ACT 2 Popcorn ALL JOY Sauces - Chutney ACTOFLEM Cold & Flu Remedies (Liquid) ALL JOY Sauces - Soya ADCO Analgesics ALL JOY Sauces - Table ADCO Cold & Flu Remedies (Liquid) ALL JOY Sauces - Tomato ADCODOL Analgesics ALL JOY Sauces - Wet Pasta ADDIS Scouring Pads ALLERGEX Cold & Flu Remedies (Liquid) ADIDAS Deodorants ALLIFAS Herbs / Spices ADVANCE Laundry Bar Soap ALLSOME Rice AERO Chocolate Coated Line ALPEN Cereals - Ready To Eat AERO Moulded Slab / Bar Chocolate ALPHA Eggs AERO SOFT Toilet Paper ALPRO Pasteurised Milk AFRICAN EXTRACT ROOIBOS Face Care - Ethnic ALWAYS Sanitary Pads and Panty Liners AFRICAN SUN Toilet Paper ALZU Eggs AGRAFROST Frozen Vegetables AMASI Maas AIROMA Air Fresheners AMASI AMAHLE Maas AIRWICK Air Fresheners AMAZING Fruit Juice - Long Life -

Nielsen FMCG 2019 Category by Brand List

FUSION 2020 TECHNICAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2020 __________________________________________________________________________ 12. NIELSEN FMCG CATEGORY AND BRAND LIST - ALPHABETIC BY CATEGORY Category Brand Category Brand Acne / Ansepc Creams CLEAN AND CLEAR Baking Powder HULLEY & RICE Acne / Ansepc Creams CUTICURA Baking Powder MOIRS Acne / Ansepc Creams GARNIER Baking Powder NON BARCODE Acne / Ansepc Creams OXY Baking Powder PICK N PAY Acne / Ansepc Creams PONDS Baking Powder ROBERTSONS Air Fresheners AIROMA Baking Powder ROYAL Air Fresheners AIRWICK Baking Powder SNOWFLAKE Air Fresheners GLADE Bath Addives ANGIE Air Fresheners MYSTIFY Bath Addives AXE Air Fresheners NON BARCODE Bath Addives CLICKS Air Fresheners OUST Bath Addives CLICKS CONFINED LABEL Air Fresheners SHIELD Bath Addives DISCHEM Air Fresheners SPARKLE Bath Addives DOVE Air Fresheners TANGO Bath Addives GOOD STUFF Aluminium foil HULETTS Bath Addives HOUSEBRAND Aluminium foil PICK N PAY Bath Addives JOHNSONS BABY Aluminium foil SPAR Bath Addives LUX Aluminium foil WRAP IT Bath Addives MOUSSON Analgesics ADCO Bath Addives NAHOON Analgesics ADCODOL Bath Addives NATURES COLLECTION Analgesics ANADIN Bath Addives NIVEA Analgesics CALPOL Bath Addives NO NAME Analgesics COMPRAL Bath Addives NON BARCODE Analgesics DISPRIN Bath Addives PALMOLIVE Analgesics GEN-PAYNE Bath Addives PROTEX Analgesics GRANDPA Bath Addives RADOX Analgesics MYBULEN Bath Addives RENEW Analgesics PAINBLOCK Bath Addives RITE BRAND Analgesics PANADO Bath Addives SANEX Analgesics SUNCODIN Bath Addives SATISKIN Ansepc -

Super Creams Assorted

TAYSTI TANGY SUPER CREAMS MAYONNAISE JAR ASSORTED 6 x 750g 12 x 125g 88.58 CASE 51.20 CASE 14.76 EACH 4.27 EACH 2208 CASES = 12 PALLETS 6 x 750g 89.69 CASE 14.95 CASE 184 CASES = 1 PALLET 6 x 750g 90.60 CASE 15.10 EACH 0-92 CASES - 2 - CAPE COOKIES LUXURY ASSORTED CAPE COOKIES 12 x 500g MINI ASSORTED 12 x 200g 512.23 CASE 42.69 EACH 205.53 CASE 17.13 EACH 3 x 2kg 432.63 CASE 144.21 EACH 6 x 1kg 523.54 CASE CAPE COOKIES 87.26 EACH SNACK ASSORTMENT 12 x 400g 447.25 CASE SNACKCRAX 37.27 EACH ASSORTED 12 x 200g 6 x 800g 194.51 CASE 356.12 CASE 16.21 EACH 59.35 EACH - 3 - KRUSH 100% UHT TROPIKA EAZY ASSORTED ASSORTED 4 x 6 x 200ml 4 x 6 x 200ml 104.37 CASE 4.35 EACH 126.91 CASE 5.29 EACH RSA ONLY. SUPER M ASSORTED 4 x 6 x 300ml 250.61 CASE CUBITOS 10.44 EACH ASSORTED 12 x 40g CLOVER SNACK NUTRIKIDS YOGHURT 108.16 CASE PACK ASSORTED 9.01 EACH ASSORTED 8 x (6 x 70g) 8 x (6 x 70g) 87.33 CASE 10.92 EACH 99.64 CASE 12.46 EACH - 4 - MILO FLAVOURED MILK CHOCOLATE CADBURY DAIRY MILK BUBBLY 4 x 6 x 200ml OREO 170.02 CASE 12 x 95g 7.08 EACH RSA & LESOTHO ONLY. 167.91 CASE 13.99 EACH CADBURY CHOCOLATE 5 STAR CADBURY 32 x 48.5g CHOCOLATE LARGE BARS ASSORTED 231.20 CASE 7.23 EACH 40 x 48g CADBURY DAIRY MILK 289.00 CASE 7.23 EACH BUBBLY 24 x 87g 369.90 CASE 15.41 EACH - 5 - OREO COOKIES KELLOGG’S ALL ASSORTED BRAN FLAKES 36 x 152g 12 x 1kg 514.05 CASE 689.69 CASE 14.28 EACH RSA & LESOTHO ONLY. -

Palm Oil Guide Worldwide Demand for Palm Oil Is Expected to Double by 2050

HOW YOUR DAILY ROUTINE CAN HELP THE RAINFOREST PALM OIL GUIDE WORLDWIDE DEMAND FOR PALM OIL IS EXPECTED TO DOUBLE BY 2050 ANIMALS THREATENED BY PALM OIL DEVELOPMENTS 50 OF SUPERMARKET PRODUCTS CONTAIN PALM OIL BUFFALO CHIMPANZEE ELEPHANT GORILLA MANATEE WORLD CONSUMPTION 62M IN 2015 DEFORESTATION RATE TONNES IN CONGO BASIN FORESTS SET TO DOUBLE DUE TO NEW PALM OIL BY 2050 X2 DEVELOPMENTS 120-156M BY 2020 TONNES THREATS TO 9,225 MT 8,620 MT RAINFOREST PEOPLE 6,850 MT LOSS OF NATURAL FOREST FOOD MEDICINE INSECURITY INDIA INDONESIA EUROPE WATER LAND RIGHTS THE EU IS THE THIRD LARGEST POLLUTION VIOLATED CONSUMER OF PALM OIL (METRIC TONS=1000KG) BISCUITS. BREAD. SHAMPOO. CHOCOLATE. DETERGENT. THESE EVERYDAY ITEMS HAVE ONE THING IN COMMON: THEY ARE A THREAT TO RAINFORESTS The list of products containing palm oil Now large-scale palm oil producers have seems almost endless. Palm oil is found turned their attention to the Congo Basin in around half of supermarket products, rainforests of Central Africa, where more like soaps and shampoos, and in many than half a million hectares of forest are kinds of food. Producing the oil often imminently threatened. involves felling virgin rainforest, reducing biodiversity, destroying the habitat of In the Congo we still have time to prevent endangered species such as orangutans, the social and environmental tragedies elephants and tigers, and ruining the caused by industrial palm oil production livelihoods of local people. in South East Asia. The demand for palm oil has already But we need to act now. devastated millions of hectares of rainforest in Malaysia and Indonesia. -

Nestlé UK Ltd Nutritional Information

Vegetarian Updated January 2013 Nestlé UK Ltd Nutritional Information Nestlé Goods brought into the UK direct by retailers Nestlé UK Ltd is part of a large international company, which produces many different products world-wide. As a recipient of the enclosed nutritional information list you will be aware of our commitment to provide up to date and correct information about our products. Recently some UK retailers have been importing Nestlé products from both Europe and other countries without our knowledge and as a result we are unable to guarantee that these imported Nestlé products are suitable for your allergy/intolerance. While appearing to be superficially similar to their UK counterparts, there are often recipe and production differences according to the country of origin. We can, however, guarantee that Nestlé products produced in the UK and shown on this list are suitable for your allergy/ intolerance. For your own safety, please check the label of the product that you have purchased – even if you have eaten the product before If you are unsure please contact us and we will do our best to help you. You can contact us free on 00800 637 85385. Our website address is www.nestle.co.uk – you can email us from the ‘contact us’ screen or use our callback service – ‘click to call’. 1 Vegetarian Updated January 2013 Foods Suitable for a Vegetarian Diet Products listed in bold are recent additions/alterations. Product Suitable for Vegetarians Beverages Coffeemate Original Light Nescafe Alta Rica Alta Rica Nescafe Azera Azera Nescafe Black -

Below Is a List of but Not Necessiaryly All Chocolate Brands World Wide. MANUFACTURER BRAND NAME DISTRIBUTION DESCRIPTION PAGE 1 A

RETURN TO “ALL OF OUR ROOTS ARE AFRICAN" Below is a list of but not necessiaryly all chocolate brands world wide. MANUFACTURER BRAND NAME DISTRIBUTION DESCRIPTION PAGE 1 A. Korkunov Korkunov chocolate bars Russia Milk and dark chocolate bars, plain, or with almonds or hazelnuts A. Loacker Co. Gardena Chocolate-orange or hazelnut cream filling in wafers covered with milk chocolate Adams and Brooks Cup-o-Gold United States Chocolate cup with a marshmallow center with almonds and coconut Ambrosoli Orly Chile Milk chocolate with fruit-flavoured creamy filling Anand Mills Union Amul Chocolate India Available in orange, milk and chocolate flavors Limited,India Annabelle Candy Company Rocky Road United States Marshmallow topped with cashews and covered with chocolate Annabelle Candy Company U-No Bar United States Milk Chocolate truffle-like center, covered with Milk Chocolate and ground almonds Annie's candy manufacturing Hany Milk Chocolate Philippines A soft milk chocolate bar Brockmann's Chocolates Inc Truffini Delta,B.C.,Canada All-natural, non-hydrogenated oils, filled truffle Brown and Haley Mountain Bar United States Vanilla, cherry, or peanut butter creme filling, covered in chocolate and peanuts in the shape of Mount Rainier Cachet India Sklofts India 5 sections: chocolate coated almonds, hazelnuts, raisins, butterscotch, cranberries Cadbury Top Deck South Africa White chocolate peaks layered on top of a milk chocolate base CAMPCO Chocolate Factory Turbo India Noughat Filled Creamy Chocolate Cavalier Woodies Belgium Milk chocolate bar with hazelnut or orange filling and a biscuit Chicken Ltd Ashmelia Ukraine Chocolate with kiwi flavoring Chocoworks Chocoelf Singapore More than 50 types of sugar-free and no Sugar-added chocolate bars Cocoa Processing Co. -

PAMS CPS Fusion 2018 Category by Brand List

PAMS 2017 TECHNICAL REPORT APRIL 2018 7. FUSION CATEGORY AND BRAND LISTS – ALPHABETIC BY CATEGORY Category Brand Category Brand Acne / Antiseptic Creams CLEAN AND CLEAR Analgesics PANADO Acne / Antiseptic Creams CUTICURA Analgesics PONSTAN Acne / Antiseptic Creams ESKAMEL Analgesics PRODOL Acne / Antiseptic Creams GARNIER Analgesics SPASMEND Acne / Antiseptic Creams PONDS Analgesics STILPAIN Air Fresheners AIROMA Analgesics SUNCODIN Air Fresheners AIRWICK Antiseptic Liquid DETTOL Air Fresheners GLADE Antiseptic Liquid MILTON Air Fresheners MYSTIFY Antiseptic Liquid SAVLON Air Fresheners NON BARCODE Artificial Sweeteners CANDEREL Air Fresheners OUST Artificial Sweeteners EQUAL Air Fresheners PESTROL Artificial Sweeteners EQUISWEET Air Fresheners Q-PREMIUM Artificial Sweeteners LS FOOD Air Fresheners SHAKE & VAC Artificial Sweeteners PICK N PAY Air Fresheners SHIELD Artificial Sweeteners SELATI Air Fresheners TANGO Artificial Sweeteners SPAR Aluminium foil COOKMASTER Artificial Sweeteners SUGANON Aluminium foil HOUSEBRAND Baking Powder HULLEY & RICE Aluminium foil HULETTS Baking Powder MOIRS Aluminium foil PICK N PAY Baking Powder NON BARCODE Aluminium foil RITE BRAND Baking Powder PICK N PAY Aluminium foil SPAR Baking Powder ROBERTSONS Aluminium foil SYLKO Baking Powder ROYAL Aluminium foil TUFFY Baking Powder SNOWFLAKE Aluminium foil WRAP IT Bath Additives ANGIE Analgesics ADCO Bath Additives CLICKS Analgesics ADCODOL Bath Additives CLICKS CONFINED LABEL Analgesics ANADIN Bath Additives CONNIE Analgesics ASHTON Bath Additives DETTOL Analgesics -

In Brief Sixteen Percent of the Cranford Incentives

tiny Liechtenstein Cranford Baseball League How The Don won QD. European tour teams win area tournaments in new 'Introductions' See Page B-1 Details on Classified Page 7 Ticket contest, details Page A-10 : • • • • . • ••.' •••.•*• SERVING CRANFORD, GARWOOD and KENILWORTH A Forbes Newspaper USPS 136 800 Second Class Vol.'98'No. 30 PublishedEveiyThursday Thursday, July 25, 1991 Postage Paid Cranford, N. J. 50 CENTS School board accepts payment compromise from Town Committee By Cheryl Moulton Township Committee and Board The problem started whep the of Education compromised Mon- state held up.approval of the 1991 day night Although initially it j^jjpj^jg^^^g seemed the^ school board was" about the inability of the county going to stand tough on the town's "strike the tax rate, whichcaused inability to make the $3.8 million the town to wait to send out town- tax levy payment by Aug. 9, after ship tax bills to residents, which two hours of debating the issue made unavailable the $3.8 million board* members agreed to allow tax levy to the Board of Educa- the township to delay total pay- tion. Force tried to explain the ment until Sept 1 while paying all board bills until them. school board was a victim of cir- cumstances, as was the township, Most board members came pre- which ultimately saw some of the pared to "go to court" if necessary cbnfusiori clear for board mem- in order to get much needed dol- bers. lars due them by state law, bring- ing with them an assortment of Although the Board of Educa- preconceived notions about why tion can invest monies they re- the township could not make the ceive from the township, they payment It appeared crossed sig- have no capacity to borrow funds, nals, misinformation and ruffled relying completely on the town- feathers had brought about their ship for monetary support State 1 c attitude, with little of "the true statutes provide protection for the facts being known.