INVESTIGATION INTO HIRING and Conduct of FORMER TARC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

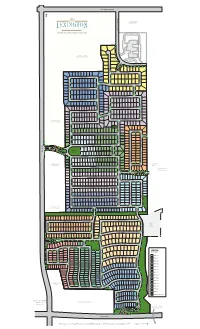

Lexington Phases Mastermap RH HR 3-24-17

ELDORADO PARKWAY MAMMOTH CAVE LANE CAVE MAMMOTH *ZONED FUTURE LIGHT RETAIL MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY MAJESTIC PRINCE CIRCLE MAMMOTH CAVE LANE T IN O P L I A R E N O D ORB DRIVE ARISTIDES DRIVE MACBETH AVENUE MANUEL STREETMANUEL SPOKANE WAY DARK STAR LANE STAR DARK GIACOMO LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDSTONE MANOR GRINDSTONE FUNNY CIDE COURT FUNNY THUNDER GULCH WAY BROKERS TIP LANE MANUEL STREETMANUEL E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND TRAIL LEONATUS LANE LEONATUS PONDER LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTERGREEN DRIVE COIT ROAD COIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD COUNT TURF COUNT DRIVE AMENITY SMARTY JONES STREET CENTER STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD 2 DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY 5 CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 1 Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE FLYING EBONY STREET LIGHT RETAIL Park AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE CONQUISTADOR COURT CONQUISTADOR LUCKY DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY OXBOW AVENUE OXBOW CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 4 WHIRLAWAY DRIVE 9 IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER ROAD C WAR EMBLEM PLACE WAR A N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R I V E 14DUST COMMANDER COURT CIRCLE PASS FORWARD DETERMINE DRIVE SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUIET RD. TIM TAM CIRCLE EASY GOER AVENUE LEGEND PILLORY DRIVE PILLORY BY PHASES HALMA HALMA TRAIL 11 PHASE 1 A PROUD CLAIRON STREET M E MIDDLEGROUND PLACE -

Download the June 20 Issue of the 2020 Special

Saturday, June 20, 2020 Year 1 • No. 3 The 2020 Unique Thoroughbred Racing Coverage Since 2001 New York’s Finest Tiz The Law rolls up on Belmont as Triple Crown finally begins Scott Serio/Eclipse Sportswire 2 THE 2020 SPECIAL SATURDAY, JUNE 20, 2020 here&there...in racing Presented by Shadwell Farm Tod Marks Honk for Racing. The only spectators permitted at the Middleburg Spring Races last week were geese. Invocation (5) led here and won the cross-country race. NAMES OF THE DAY Belmont Park BY THE NUMBERS 115: Starters at the Middleburg Spring Races steeplechase meet June 13 – the first steeplechase racing in the United Second Encore, first race. Larry Smith’s 5-year-old is out of 1: Recent hurdle winner in France for Team Valor Internation- States since November. Two Bows. Smith’s band Release – “All the band you’ll ever al. Nathanielhawthorne, an English-bred 4-year-old by Nathan- need” – might take an occasional second encore. iel, won a handicap hurdle for trainer David Cottin at Compie- 47: Riding wins by Barclay Tagg on the U.S. steeplechase gne June 13. circuit (1966-77). No Parole, second race. Owned by Maggi Moss and Greg Tramontin, the 3-year-old Woody Stephens contender is by 18: Grade 1 stakes on the Saratoga calendar for 2020, includ- 2: Starts earlier than May 1, in 36 lifetime starts by turf sprint- Violence. ing the Whitney Aug. 1 and Travers Aug. 8. er Pure Sensation who makes his seasonal debut in the Jaipur at Belmont Park Saturday. Breaking The Rules, 11th race. -

Lex Mastermap Handout

ELDORADO PARKWAY M A MM *ZONED FUTURE O TH LIGHT RETAIL C A VE LANE MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY M A J E MAMMOTH CAVE LANE S T T IN I C O P P L I R A I N R E C N E O C D I R C L ORB DRIVE E A R I S T MACBETH AVENUE I D E S D R I V E M SPOKANE WAY D ANUEL STRE ARK S G I A C T O AR LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 M O E L T A N E 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDS FUN N T Y CIDE ONE THUNDER GULCH WAY M C ANOR OU BROKERS TIP LANE R T M ANUEL STRE E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A E T DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND VIEW LEON PONDER LANE A TUS LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTE R GREEN DRIVE C OIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD C OUNT R O TURF DRIVE AD S AMENITY M A CENTER R T Y JONES STRE STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD E T L 5 2 UC K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 1 A Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE V FLYING EBONY STREET A LIGHT RETAIL L C Park ADE DRIVE AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE C L ONQUIS UC O XBOW K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 4 T A ADOR V A A VENUE L C ADE DRIVE WHIRLAWAY DRIVE C OU R 9T IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER C W A AR EMBLEM PL N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R A O R CE I AD V E DUST COMMANDER COURT FO DETERMINE DRIVE R W ARD P 14 ASS CI SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUI R CLE E T R TIM TAM CIRCLE D . -

Testimony of Marty Irby Executive Director Animal Wellness Action Before the U.S

Testimony of Marty Irby Executive Director Animal Wellness Action before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Commerce and Consumer Protection H.R. 1754, "The Horseracing Integrity Act" January 28, 2020 On behalf of Animal Wellness Action, one of the nation's leading animal protection organizations on Capitol Hill, I submit this testimony in support of H.R. 1754, the Horseracing Integrity Act. I express my sincere thanks to Chair Jan Schakowsky and Ranking Member Cathy McMorris Rodgers for conducting this hearing and offer special thanks to Representatives Paul Tonko, and, Andy Barr for introducing this reform effort. I also express thanks to Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Frank Pallone and Ranking Member Greg Walden for their participation in this process. This hearing builds on the testimony and other information gathered during the 2018 hearing conducted before the Subcommittee on H.R. 2651 in the 115th Congress. I first want to underscore that Animal Wellness Action does not oppose horseracing. We join with many horse owners, breeders, trainers, and racing enthusiasts in speaking out on the broader topic of the protection of horses within the American horseracing industry and across the greater equine world. We seek to promote the proper stewardship of horses at every stage of their lives, including during their racing careers. We are deeply concerned about on- and off- track risks to the horses, including catastrophic injuries sustained during racing. America was built on the backs of horses, and they have always played a central role in the economy and culture of the United States. We owe them a debt of gratitude, and the very least we must do is ensure their safety, welfare, and protection. -

PEDIGREE INSIGHTS Marty Wygod, Felt It Necessary to Have Him Gelded

Andrew Caulfield, December 17-Shared Belief To me, his only flaw is that his breeders, Pam and PEDIGREE INSIGHTS Marty Wygod, felt it necessary to have him gelded. B Y A N D R E W C A U L F I E L D Needless to say, that operation is no bar to victory in the Kentucky Derby, as Funny Cide and Mine That Bird Saturday, Betfair Hollywood Park have demonstrated in recent years. CASHCALL FUTURITY-GI, $751,500, BHP, 12-14, 2yo, Jerry Hollendorfer=s assistant Dan Ward said of 1 1/16m (AWT), 1:42, ft. Shared Belief that Ahe=s not a huge horse, but he=s 1--sSHARED BELIEF, 121, g, 2, by Candy Ride (Arg) growing all the time.@ But then his sire Candy Ride isn=t 1st Dam: Common Hope, by Storm Cat a big horse either, at just half an inch over 16 hands, 2nd Dam: Sown, by Grenfall and that didn=t stop him shining at the ages of three 3rd Dam: Bad Seed, by Stevward and four. That statement needs a little footnote. O-Jungle Racing LLC, KMN Racing LLC, Hollendorfer, Although Candy Ride was officially four when he won Litt, Solis II & Todaro; B-Pam & Martin Wygod (KY); the GII American H. and the GI Pacific Classic in 2003, T-Jerry Hollendorfer; J-Corey S Nakatani. $375,000. he was still a month short of his actual fourth birthday Lifetime Record: 3-3-0-0, $451,200. *1/2 to Little when he defeated Medaglia d=Oro by more than three Miss Holly (Maria=s Mon), GSW, $217,430; Double lengths in the Del Mar feature. -

DARK BAY OR BROWN FILLY Barn 24 Hip No

Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock, Agent II Hip No. DARK BAY OR BROWN FILLY Barn 505 Foaled March 13, 2017 24 Empire Maker Pioneerof the Nile ................ Star of Goshen American Pharoah ................ Yankee Gentleman Littleprincessemma .............. Exclusive Rosette DARK BAY OR Dixieland Band BROWN FILLY Dixie Union .......................... She's Tops Theycallmeladyluck .............. (2005) Crafty Prospector Vegas Prospector .................. Hill Billy Dancer By AMERICAN PHAROAH (2012). Horse of the year, Triple Crown winner of 9 races in 11 starts at 2 and 3, $8,650,300, Kentucky Derby [G1] (CD, $1,- 418,800), Xpressbet.com Preakness S. [G1] (PIM, $900,000), Belmont S. [G1] (BEL, $800,000), Breeders' Cup Classic [G1] (KEE, $2,750,000)-ntr, William Hill Haskell Invitational S. [G1] (MTH, $1,100,000), Arkansas Derby [G1] (OP, $600,000), Del Mar Futurity [G1] (DMR, $180,000), FrontRunner S. [G1] (SA, $180,000), etc. His first foals are yearlings of 2018 . 1st dam Theycallmeladyluck , by Dixie Union. Winner at 3 and 4, $52,460, 3rd Hoist Her Flag S. (CBY, $6,000). Dam of 4 other registered foals, 4 of racing age, including a 2-year-old of 2018, 3 to race, 2 winners, including-- SALTY (f. by Quality Road). 4 wins at 3 and 4, 2018, $688,500, La Troienne S. [G1] (CD, $214,830), Gulfstream Park Oaks [G2] (GP, $150,350), 2nd Acorn S. [G1] (BEL, $130,000), 3rd Alabama S. [G1] (SAR, $60,000), Coaching Club American Oaks [G1] (SAR, $30,000). 2nd dam VEGAS PROSPECTOR , by Crafty Prospector. 7 wins, 2 to 5, $297,232, Ci - cada S. [G3] , Miss Woodford S. -

Kentucky Derby Winners Vs. Kentucky Derby Winners

KENTUCKY DERBY WINNERS VS. KENTUCKY DERBY WINNERS Winners of the Kentucky Derby have faced each other 43 times. The races have occurred 17 times in New York, nine in California, nine in Maryland, six in Kentucky, one in Illinois and one in Canada. Derby winners have run 1-2 on 12 occasions. The older Derby winner has prevailed 24 times. Three Kentucky Derby winners have been pitted against one another twice, including a 1-2-3 finish in the 1918 Bowie Handicap at Pimlico by George Smith, Omar Khayyam and Exterminator. Exterminator raced against Derby winners 15 times and finished ahead of his rose-bearing rivals nine times. His chief competitor was Paul Jones, who he beat in seven of 10 races while carrying more weight in each affair. Date Track Race Distance Derby Winner (Age, Weight) Finish Derby Winner (Age, Weight) Finish Nov. 2, 1991 Churchill Downs Breeders’ Cup Classic 1 ¼ M Unbridled (4, 126) 3rd Strike the Gold (3, 122) 5th June 26, 1988 Hollywood Park Hollywood Gold Cup H. 1 ¼ M Alysheba (4,126) 2nd Ferdinand (5, 125) 3rd April 17, 1988 Santa Anita San Bernardino H. 1 1/8 M Alysheba (4, 127) 1st Ferdinand (5, 127) 2nd March 6, 1988 Santa Anita Santa Anita H. 1 ¼ M Alysheba (4, 126) 1st Ferdinand (5, 127) 2nd Nov. 21, 1987 Hollywood Park Breeders’ Cup Classic 1 ¼ M Ferdinand (4, 126) 1st Alysheba (3, 122) 2nd Oct. 6, 1979 Belmont Park Jockey Club Gold Cup 1 ½ M Affirmed (4, 126) 1st Spectacular Bid (3, 121) 2nd Oct. 14, 1978 Belmont Park Jockey Club Gold Cup 1 ½ M Seattle Slew (4, 126) 2nd Affirmed (3, 121) 5th Sept. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

CITY of FLORISSANT STREET GUIDE Street Name Address Range Zip Code Ward Description of Street

CITY OF FLORISSANT STREET GUIDE Street Name Address range Zip Code Ward Description of street Acredale 1180-1415 63033 7 Dunn & S. Waterford. 1st Street Hadwin which is 2nd street North of Dunn on S. Waterford. Aintree Drive 1420-1560 (Even) 63033 8 Parker Spur & New Halls Ferry. Runs from Waterford to New Halls Ferry; 1st street north of Parker Spur 1425-1565 (Odd) 63033 9 Parker Spur & New Halls Ferry. Runs from Waterford to New Halls Ferry; 1st street north of Parker Spur Alandale Court 2-24 63031 2 Lindsay Lane & N. Hwy 67 Runs off Lindsay Lane. 2nd street NW of N Hwy 67. Albert Drive 190-470 and 85- 63031 3 Charbonier & Shackelford. 2nd street on right from 145 Shackelford SE on Charbonier (190-470). Charbonier & Howdershell. SW on Howdershell to 2nd left, Flordawn. Flordawn to the 1st street, Albert. Albert runs between Croftdale and Layven (85-145) Alberto Lane 70-170 63031 2 Lindsay Lane & Schackelford or Charbonier & Shackelford. Off Monterey or Eldorado 4th street on right off Lindsay from Shackelford is Eldorado. OR Charbonier to Ocala to Loekes left to Florisota left to Alberto. Allen Drive 1860-1880 W-E 63033 5 New Florissant Road North & St. Catherine. East on St. Catherine to Larry Drive, right to 1800 -1860 Allan; or continue on St. Catherine to 500 Allan. Also St. Anthony east to St. Edward, left to 1900 Allan Drive(1st cross st.) * Designates streets not city maintained Revised September 2016 Page 1 of 134 Street Name Address range Zip Code Ward Description of street Allen Drive 1900-1920 63033 5 New Florissant Road North & St. -

Supporters of the American Horse Slaughter Prevention Act (H.R

SUPPORTERS OF THE AMERICAN HORSE SLAUGHTER PREVENTION ACT (H.R. 503) UNational Horse Industry Organizations UThe American Holsteiner Horse Association, Inc. The American Sulphur Horse Association American Indian Horse Registry Blue Horse Charities Churchill Downs Incorporated Eaton & Thorne Eaton Sales, Inc. Fasig-Tipton Company, Inc. Hambletonian Society, Inc. Horse Connection Magazine Horse Industry Partners Hughs Management Keeneland Association Inc. Magna Entertainment Corp. National Show Horse Registry National Steeplechase Association, Inc. National Thoroughbred Racing Association New York Racing Association New York State Thoroughbred Racing and Development Fund Corporation New York Thoroughbred Breeders, Inc. Ocala Breeder's Sales Company (OBS) Palomino Horse Association, Int. Racetrack Chaplaincy of America Thoroughbred Racing Protective Bureau Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation United States Eventing Association Walnut Hall Limited UHorse Industry Leaders UJosephine Abercrombie – Owner, Pin Oak Stud Joe L. Allbritton – Owner, Lazy Lane Farms, Inc. Peggy Augustus – Owner, Keswick Farm Niall and Stephanie Brennan – Niall Brennan Stables Nadia Sanan Briggs – Padua Stables Maggie O. Bryant – Locust Hill Farm W. Cothran "Cot" Campbell – Dogwood Stables Norman Casse – Chairman of the Ocala Breeder's Sales Company (OBS) Nick and Jaqui de Meric – Nick de Meric Bloodstock Richard L. Duchossois – Chairman, Arlington Park Tracy & Carol Farmer – Owners, Shadowlawn Farm John Fort – Peachtree Racing Stable John Gaines – the late founder of -

RUNNING STYLE at Quarter Mile Decidedly 1962 9 9 ¼ Carry Back 1961 11 18

RUNNING STYLE At Quarter Mile Decidedly 1962 9 9 ¼ Carry Back 1961 11 18 Venetian Way 1960 4 3 ½ Wire-To-Wire Kentucky Derby Winners : Horse Year Call Lengths Tomy Lee 1959 2 1 ½ American Pharoah 2015 3 1 Tim Tam 1958 8 11 This listing represents 22 Kentucky Derby California Chrome 2014 3 2 Iron Liege 1957 3 1 ½ winners that have led at each point of call during the Orb 2013 16 10 Needles 1956 16 15 race. Points of call for the Kentucky Derby are a I’ll Have Another 2012 6 4 ¼ quarter-mile, half-mile, three-quarter-mile, mile, Swaps 1955 1 1 Animal Kingdom 2011 12 6 Determine 1954 3 4 ½ stretch and finish. Super Saver 2010 6 5 ½ From 1875 to 1959 a start call was given for Dark Star 1953 1 1 ½ Mine That Bird 2009 19 21 Hill Gail 1952 2 2 the race, but was discontinued in 1960. The quarter- Big Brown 2008 4 1 ½ Count Turf 1951 11 7 ¼ mile then replaced the start as the first point of call. Street Sense 2007 18 15 Middleground 1950 5 6 Barbaro 2006 5 3 ¼ Ponder 1949 14 16 Wire-to-Wire Winner Year Giacomo 2005 18 11 Citation 1948 2 6 Smarty Jones 2004 4 1 ¾ War Emblem 2002 Jet Pilot 1947 1 1 ½ Funny Cide 2003 4 2 Winning Colors-f 1988 Assault 1946 5 3 ½ War Emblem 2002 1 ½ Spend a Buck 1985 Hoop Jr. 1945 1 1 Monarchos 2001 13 13 ½ Bold Forbes 1976 Pensive 1944 13 11 Riva Ridge 1972 Fusaichi Pegasus 2000 15 12 ½ Count Fleet 1943 1 head Kauai King 1966 Charismatic 1999 7 3 ¾ Shut Out 1942 4 2 ¼ Jet Pilot 1947 Real Quiet 1998 8 6 ¾ Whirlaway 1941 8 15 ½ Silver Charm 1997 6 4 ¼ Count Fleet 1943 Gallahadion 1940 3 2 Grindstone 1996 15 16 ¾ Bubbling Over 1926 Johnstown 1939 1 2 Thunder Gulch 1995 6 3 Paul Jones 1920 Lawrin 1938 5 7 ½ Go for Gin 1994 2 head Sir Barton 1919 War Admiral 1937 1 1 ½ Sea Hero 1993 13 10 ¾ Regret-f 1915 Bold Venture 1936 8 5 ¾ Lil E. -

Living His Dream in Santa Anita

NA TRAINER LEWIS ISSUE 34_Jerkins feature.qxd 23/10/2014 00:51 Page 1 PROFILE CRAIG LEWIS Living his dream in Santa Anita Craig Anthony Lewis is a racetrack lifer. And at 67, if genealogy and longevity mean anything, he still has a long way to go as a trainer. His father, Seymour, is 92. His mother, Norma, is 90. They still live together in Seal Beach, California. WORDS: ED GOLDEN PHOTOS: HORSEPHOTOS 14 TRAINERMAGAZINE.com ISSUE 34 NA TRAINER LEWIS ISSUE 34_Jerkins feature.qxd 23/10/2014 00:51 Page 2 CRAIG LEWIS ISSUE 34 TRAINERMAGAZINE.com 15 NA TRAINER LEWIS ISSUE 34_Jerkins feature.qxd 23/10/2014 00:51 Page 3 PROFILE O “senior complexes” for them. No depressing assisted living warehouses. “My father still drives,” Craig says. “He’s sharper than I am.” NThat’s a mouthful from Lewis who, while not verbose when he speaks, is all meat and potatoes…as straight as Princess Kate’s teeth. Little wonder he knows his way around the track. He began his training career in 1978 and got his first taste of racing before it was time for his Bar Mitzvah. “I used to go to the track when I was a kid with my dad and that’s how I got started,” Lewis said. “I was fascinated by horse racing. I would go to Caliente on weekends with my brother. I was nine and he was 10. We were betting quarters with bookmakers and just kind of got swept up by it all.” More than half a century later, the broom still has bristles, thanks in small part to Lewis’ affiliation early on with legendary trainer Hirsch Jacobs, whose remarkable achievements have faded into racing’s Graded stakes winner Za Approval, Lee Vickers up, trots by Clement on the way to the track hinterlands over time.