The Ash Dieback Pathogen Hymenoscyphus Pseudoalbidus Is Associated with Leaf Symptoms on Ash Species (Fraxinus Spp.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacson Ferreira Versao Revisada.Pdf

Universidade de São Paulo Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz” Identificação molecular de um fitoplasma associado a árvores de oliveira com sintoma de vassoura-de-bruxa Jacson Ferreira Dissertação apresentada para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências. Área de concentração: Fitopatologia Piracicaba 2017 Jacson Ferreira Bacharel em Agronomia Identificação molecular de um fitoplasma associado a árvores de oliveira com sintoma de vassoura-de-bruxa versão revisada de acordo com a resolução CoPGr 6018 de 2011 Orientador: Prof. Dr. IVAN PAULO BEDENDO Dissertação apresentada para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências. Área de concentração: Fitopatologia Piracicaba 2017 2 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação DIVISÃO DE BIBLIOTECA – DIBD/ESALQ/USP Ferreira, Jacson Identificação molecular de um fitoplasma associado a árvores de oliveira com sintoma de vassoura-de-bruxa/ Jacson Ferreira. - - versão revisada de acordo com a resolução CoPGr 6018 de 2011. - - Piracicaba, 2017 45p. Dissertação (Mestrado) - - USP / Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz”. 1. Mollicutes 2. Superbrotamento de ramos 3. Grupo 16SrVII-B fitoplasmas I. Título 3 Dedico a Deus por ter trilhado o meu caminho, pois sem ti nada sou e nada posso fazer. A minha mãe Joana, ao meu pai José e ao meu irmão Everton, por sempre estarem ao meu lado. “O cientista não é o homem que fornece as verdadeiras respostas; é quem faz as verdadeiras perguntas.” Claude Lévi-Strauss OFEREÇO: José Ferreira Soares (In memorian) 4 AGRADECIMENTOS A Deus por sempre estar presente em minha vida guiando meu caminho. Aos meus pais e ao meu irmão pelo apoio. Ao prof. Dr. Ivan Paulo Bedendo pela orientação, incentivo e colaboração. -

Seed Chemical Composition of Endemic Plant Fraxinus Ornus Subsp

Tonguç: Seed chemical composition of endemic plant Fraxinus ornus subsp. cilicica - 8261 - SEED CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF ENDEMIC PLANT FRAXINUS ORNUS SUBSP. CILICICA TONGUÇ, F. Isparta Applied Sciences University, Faculty of Forestry, Isparta, Turkey (e-mail: [email protected]; phone: +90-246-211-3989; fax: +90-246-211-3948) (Received 25th Feb 2019; accepted 15th May 2019) Abstract. The present study was conducted to determine the biochemical characteristics of Fraxinus ornus subsp. cilicica, seeds, an endemic tree species of Turkey. Seeds were collected from three provenances (Düziçi-Osmaniye, Andırın-Kahramanmaraş, Pozantı-Adana). Seed reserve composition (total soluble sugars, reducing sugars, carotenoids, xanthophylls, total soluble proteins, total tocopherol, total soluble phenolics, flavanoids and oil content) and seed fatty acids contents were examined. Total soluble sugars content and total tocopherol contents of seed among provenances did not differ significantly but other seed constituents were different among provenances. The highest amount of fatty acids present in F. ornus subsp. cilicica seeds were linoleic and oleic acids. The present study is the first report dealing with various aspects of seed composition and should provide valuable information for this endemic species. Keywords: fatty acids, manna ash, taurus flowering ash, oil content, provenance Introduction Fraxinus ornus (L.) (Oleaceae), also known as Manna ash (Fraxigen, 2005), can be used for numerous purposes for example, afforestation/reforestation of deforested areas, urban landscape design, forest restoration and manna production. Manna refers to white or faded yellow sugary substance that dried exudates collected from diverse natural sources and used in several locations around the world as a traditional sweet, emergency food or traditional medicine to treat trivial diseases (Harrison, 1950). -

2014-2024 Management Plan Prespa National Park in Albania

2014-2024 Management Plan Prespa National Park in Albania MANAGEMENT PLAN of the PRESPA NATIONAL PARK IN ALBANIA 2014-2024 1 2014-2024 Management Plan Prespa National Park in Albania ABBREVIATIONS ALL Albanian Lek a.s.l. Above Sea Level BCA Biodiversity Conservation Advisor BMZ Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, Germany CDM Clean Development Mechanism Corg Organic Carbon DCM Decision of Council of Ministers DFS Directorate for Forestry Service, Korca DGFP Directorate General for Forestry and Pastures DTL Deputy Team Leader EUNIS European Union Nature Information System GEF Global Environment Facility GFA GFA Consulting Group, Germany GNP Galicica National Park GO Governmental Organisation GTZ/GIZ German Agency for Technical Cooperation, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (Name changed to GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit) FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature The World Conservation Union FUA Forest User Association Prespa KfW Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau - Entwicklungsbank/German Development Bank LMS Long Term Monitoring Sites LSU Livestock Unit MC Management Committee of the Prespa National Parkin Albania METT Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool MoE Ministry of Environment of Albania MP Management Plan NGO Non-Governmental Organisation NP National Park NPA National Park Administration NPD National Park Director (currently Chief of Sector of Directorate for Forestry Service, Korca) PNP National -

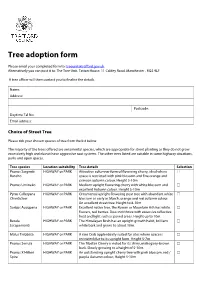

Tree Adoption Form

Tree adoption form Please email your completed form to: [email protected]. Alternatively you can post it to: The Tree Unit, Tatton House, 11 Caldey Road, Manchester , M23 9LF A tree officer will then contact you to finalise the details. Name: Address: Postcode: Daytime Tel No: Email address: Choice of Street Tree Please tick your chosen species of tree from the list below. The majority of the trees offered are ornamental species, which are appropriate for street planting as they do not grow excessively high and do not have aggressive root systems. The other trees listed are suitable in some highway situations, parks and open spaces. Tree species Location suitability Tree details Selection Prunus Sargentii HIGHWAY or PARK Attractive columnar form of flowering cherry, ideal where ☐ Rancho space is restricted with pink blossom and fine orange and crimson autumn colour. Height 5-10m Prunus Umineko HIGHWAY or PARK Medium upright flowering cherry with white blossom and ☐ excellent Autumn colour. Height 5-10m Pyrus Calleryana HIGHWAY or PARK Ornamental upright flowering pear tree with abundant white ☐ Chanticleer blossom as early as March, orange and red autumn colour. An excellent street tree. Height to 8-10m Sorbus Aucuparia HIGHWAY or PARK Excellent native tree, the Rowan or Mountain Ash has white ☐ flowers, red berries. Does not thrive with excessive reflective heat and light such as paved areas. Height up to 10m. Betula HIGHWAY or PARK The Himalayan Birch has an upright growth habit, brilliant ☐ Jacquemonti white bark and grows to about 10m. Malus Trilobata HIGHWAY or PARK A rare Crab apple ideally suited for sites where space is ☐ restricted due to its upright form. -

Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Hacıosman Ormanı Tabiatı Koruma

BEÜ Fen Bilimleri Dergisi BEU Journal of Science 9 (1), 168-193, 2020 9 (1), 168-193, 2020 Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Hacıosman Ormanı Tabiatı Koruma Alanı (Samsun) Florası, Vejetasyon ve Habitat Yapısı ile Genel Bitki Ekolojisi Özellikleri Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme Okan ÜRKER* Çankırı Karatekin Üniversitesi, Eldivan Sağlık Hizmetleri MYO, Tıbbi Hizmetler ve Teknikler Bölümü, Çevre Sağlığı Programı, Çankırı (ORCID: 0000-0002-5103-7757) Öz Samsun İli, Çarşamba İlçesi sınırlarında yer alan Hacıosman Ormanı Tabiatı Koruma Alanı içerisinde ekosistem tiplerinin belirlenmesi ve Tabiatı Koruma Alanı'nın floristik özelliklerinin gözlemlenmesi amacıyla 2017 yılı Mart, Haziran, Eylül ve Aralık aylarında çeşitli lokalitelerde hat-transekt metodu uygulanarak genel bitki ekolojisi, flora, vejetasyon ve habitat özelliklerine ait gözlemler gerçekleştirilmiş olup, 94 familya, 227 cins ve bu cinslere ait 271 damarlı bitki takson tespit edilmiştir. Alanda sazlık-bataklık, geçici subasar ormanı, orman ve dere ekosistemleri bir arada bulunmaktadır. Bu nedenle alan küçük olmasına rağmen farklı habitat ve ekosistem tiplerini içerdiğinden zengin bir biyolojik çeşitliliğe sahiptir. Tabiatı Koruma Alanı, Doğal Sit Alanı ve aynı zamanda Önemli Bitki Alanı koruma statülerini bünyesinde barındıran Hacıosman Ormanı, hem Avrupa’da da nadir bulunan kalıntı alüvyal su basar ormanlardan biri olması nedeniyle hem de içerdiği ekosistem tipleri ve biyolojik çeşitlilik unsurları, nadirlik ve tipiklik bakımından oldukça önem arz etmektedir. Çalışma alanında tespit edilen damarlı bitki taksonları içerisinden her ne kadar endemik ve nadir türlere rastlanılmamış olmakla beraber izlemeye konu olabilecek 4 türün varlığından söz edilebilir; bunlardan ilki IUCN Kırmızı Liste kategorilerine göre VU statüsünde yer alan Plantago lanceolata (Su sinir otu), diğeri Bern Sözleşmesi’nin Ek-1 listesi içerisinde yer alan türlerden Cyclamen coum ssp. -

MANNA ASH for LATE SPRING Dr Linda Newstrom-Lloyd (Trees for Bees Botanist) and Dr Angus Mcpherson (Trees for Bees Farm Planting Adviser)

24 NEW ZEALAND BEEKEEPER, SEPTEMBER 2019 TREES FOR BEES CORNER STAR PERFORMERS PART 7: MANNA ASH FOR LATE SPRING Dr Linda Newstrom-Lloyd (Trees for Bees Botanist) and Dr Angus McPherson (Trees for Bees Farm Planting Adviser) Trees for Bees has produced a series of fact sheets showcasing the ‘best of the best’ bee plants that will maximise nutritional benefits for your bees. In this issue of the journal, the team explains why manna ash is a ‘star performer’. For more information, see www.treesforbeesnz.org. Manna ash or flowering ash (Fraxinus Fraxinus ornus (manna ash, flowering ash) is Nectar ornus) is in the olive family (Oleaceae) a medium-sized, round-headed, deciduous After much searching, it has not been possible and helps to solve the October crash tree. It grows to a compact tree 15–25m to verify conclusively that the flowers produce problem. tall (Salmon, 1999, p.283; Appletons, 2019; any nectar but they probably do not. In TERRAIN, 2019; Easy Big Trees, 2019) but likely Manna ash is a star performer because it fills the evolution of Fraxinus flowers from their shorter in New Zealand. It has a relatively in that late spring pollen dearth gap. It flowers insect-pollinated ancestors to the derived short trunk and smooth bark. The trees are profusely during what beekeepers call ‘the state of wind pollination, the manna ash remarkable with a profusion of scented, October crash’ when there are few pollen sits in the middle as an intermediary step white fluffy clusters of flowers (Figure 1) that sources in some areas of both the North and bloom in October to November (Salmon, South Island. -

Recommended Street Tree List

City of Talent Recommended Street Tree List Common Name Linnaean Classification Ash, American/White........................................................Fraxinus Americana Ash, European Mountain..................................................Sorbus aucuparia Ash, Flowering....................................................................Fraxinus ornus Ash, Narrowleaf..................................................................Fraxinus oxycarpa Boxelder, Varigated............................................................Acer negundo Cherry, Sergeant..................................................................Prunus sargentii Cork Tree, Amur ................................................................Philodendron amurense Crabapple, Ornamental......................................................Malus spp. Crepemyrtle ........................................................................Lagerstromia indica Cypress, Bald.......................................................................Taxodium distichum Dogwood, Cornellian Cherry ...........................................Cornus mas Dogwood, Kousa ...............................................................Cornus kousa Elm, Chinese .......................................................................Ulmus parvifolia Filbert, Turkish ...................................................................Corylus colurna Ginkgo, Maidenhair Tree ..................................................Gingko biloba Goldenrain Tree .................................................................Koelreuteria -

Fraxinus Ornus (Flowering Ash) Flowering Ash, Produces a Spectacular Display of Fragrant Creamy White Flowers in May

Fraxinus ornus (Flowering Ash) Flowering ash, produces a spectacular display of fragrant creamy white flowers in May. This deciduous tree can grow up to 10-12 m. After flowering it produces an unattractive cluster of winged fruits. During fall the leaf can turn into deep bordo color. Also called manna ash. The tree commercially grown in Sicily for manna which is a sweet, gummy sap taken from slits made in the bark. Landscape Information French Name: Frêne à manne, Orne d'Europe Pronounciation: FRAK-si-nus OR-nus Plant Type: Tree Origin: Southern Europe and southwestern Asia Heat Zones: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Hardiness Zones: 6, 7, 8, 9 Uses: Specimen, Shade, Street, Native to Lebanon Size/Shape Growth Rate: Moderate Tree Shape: Round, oval Canopy Symmetry: Symmetrical Canopy Density: Dense Canopy Texture: Medium Height at Maturity: 8 to 15 m Spread at Maturity: 5 to 8 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 10 to 20 Years Plant Image Fraxinus ornus (Flowering Ash) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Opposite Leaf Venation: Pinnate Leaf Persistance: Deciduous Leaf Type: Odd Pinnately compund Leaf Blade: 5 - 10 cm Leaf Shape: Oval Leaf Margins: Serrulate Leaf Textures: Glossy, Medium Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Yellow, Purple Flower Flower Showiness: True Flower Size Range: 3 - 7 Flower Type: Panicle Flower Scent: Pleasant Flower Color: Green, White Seasons: Spring Trunk Trunk Has Crownshaft: False Flower Image Trunk Susceptibility to Breakage: Suspected to breakage Number of Trunks: Single -

Controlling Desert Ash (Fraxinus Angustifolia Subsp. Angustifolia): Have We Found the Silver Bullet?

Nineteenth Australasian Weeds Conference Controlling desert ash (Fraxinus angustifolia subsp. angustifolia): have we found the silver bullet? Tony M. Dugdale, Trevor D. Hunt and Daniel Clements Department of Environment and Primary Industries, Biosciences Research Division, AgriBiosciences Centre, 5 Ring Road, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3083, Australia ([email protected]) Summary Desert ash (Fraxinus angustifolia Vahl. New South Wales (Blood 2001), and is also recorded subsp. angustifolia, Oleaceae) is a weedy deciduous from Western Australia and Tasmania (CHAH 2014). tree in south-eastern Australia, particularly in riparian The largest infestations are currently located around situations. It reproduces by seed and by root suckers Melbourne, central Victoria and Adelaide. It pro- and can form monocultures displacing desirable na- duces many single seeded winged fruit (samara) which tive shrubs and trees. Very little published information spread from ornamental or streetscape plantings into is available regarding suitable control methods and creeks and river systems, wetlands, urban bushland, anecdotal reports of the effectiveness of herbicides lowland grasslands and grassy woodlands. It is typi- are variable. We conducted two trials to determine cal to find a stand or row of desert ash planted along the effectiveness of herbicides to control desert ash. a driveway, beside a road or street at the upstream From the first screening trial picloram and triclopyr end of an infestation along a watercourse (author’s + picloram were excluded, and the herbicides glypho- observations). sate, glyphosate + metsulfuron-methyl, metsulfuron- Very little published information is available methyl alone at two rates and triclopyr ester were regarding suitable control methods, and anecdotal tested further. -

Elements of Growth and Structure of Narrow-Leaved Ash (Fraxinus Angustifolia Vahl) Annual Seedlings in the Nursery on Fluvisol

PERIODICUM BIOLOGORUM UDC 57:61 VOL. 112, No 3, 341–351, 2010 CODEN PDBIAD ISSN 0031-5362 Original scientific paper Elements of growth and structure of narrow-leaved ash (Fraxinus angustifolia Vahl) annual seedlings in the nursery on fluvisol Abstract MARTIN BOBINAC1 SINI[A ANDRA[EV2 Background and Purpose: For the process of optimisation of annual MIRJANA [IJA^I]-NIKOLI]1 seedling production of narrow-leaved ash (Fraxinus angustifolia Vahl) 1 planned for the reforestation of marshland sites morphology, height and di- Faculty of Forestry. University of Belgrade ameter growth and structure of narrow-leaved ash were researched in the Kneza Vi{eslava 1 11000 Belgrade, Serbia nursery on fluvisol in different microsite conditions (microsite A – sandy- -loamy fluvisol and micrositeB–loamy fluvisol). 2 Institute of Lowland Forestry and Environment Material and Methods: The measurements included the length of the University of Novi Sad axis above the cotyledons (h), and hypocotyl diameter (d0). The length of Antona ^ehova 13d internodes and two intersecting diameters in the middle of each internode 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia were measured on three highest seedlings in the seedbed (h=208.7–223.7 Correspondence: cm). Martin Bobinac Results and Conclusion: The elements of seedling growth were af- Faculty of Forestry, University of Belgrade fected by microsite conditions and growing space. The analysis of Kneza Vi{eslava 1 covariance showed that growing space did not have a significant ef- 11000 Belgrade, Serbia E-mail: [email protected] fect on mean seedling height (ha,hL,hg20%), and on mean square di- ameter of 20% largest-diameter seedlings, which indicates that these Key words: Fraxinus angustifolia Vahl, growth elements were more affected by site conditions, i.e., indi- annual seedlings, nursery, morphology, rectly, by silvicultural treatments. -

Fraxinus Angustifolia Raywood Raywood Ash / Claret Ash

Fraxinus angustifolia Raywood Raywood Ash / Claret Ash Fraxinus angustifolia ‘Raywood’ (also known as Fraxinus oxycarpa ‘Raywood’) is a medium sized, fast growing, October deciduous tree. It has a narrow, upright crown when young and broadens 2012 into a full, rounded canopy as it matures. The most alluring feature of this tree is the foliage. Throughout the summer, the narrow, serrated leaves are dark green and glossy providing dappled shade below. They really come into their own in the Autumn though when they turn brilliant hues of purple and wine-red. Fraxinus ‘Raywood’ is also a good tree for urban and avenue planting. Its uniformity and tolerance to soil compaction make it a great choice. It also has a greater tolerance for dry soils than Fraxinus excelsior (Common Ash). The drawback however, is that the branches can be brittle and prone to breaking. The tree originates from south Australia around about 1910 and was grown at a property called ‘Raywood’. It was not introduced to the UK until 1928. Autumn colouring on Fraxinus ‘Raywood’ Plant Profile Name: Fraxinus angustifolia ‘Raywood’ Common Name: Claret Ash or Raywood Ash Family: Oleaceae Height: Approximately 15m height Demands: Ideal on a well drained soil but tolerant of a wide range of conditions. Very good in urban environments Foliage: Slender, dark-green leaves throughout summer and spectacular Autumn colouring Flowers: Inconspicuous Fruit: Does not produce fruit Narrow, dark green leaves in summer Deepdale Trees Ltd., Tithe Farm, Hatley Road, Potton, Sandy, Beds. SG19 2DX. Tel: 01767 26 26 36 www.deepdale-trees.co.uk Fraxinus angustifolia Raywood Raywood Ash / Claret Ash Originating in Southern Australia this tree did not reach British shores until 1928 Purple and red autumn foliage UndersideDark brownof a Tilia buds cordata - unlike the black buds of Fraxinus ‘Raywood’ 20-25-30cm girth leaf Common Ash Deepdale Trees Ltd., Tithe Farm, Hatley Road, Potton, Sandy, Beds. -

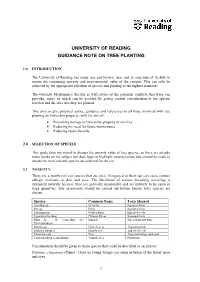

University of Reading Guidance Note on Tree Planting

UNIVERSITY OF READING GUIDANCE NOTE ON TREE PLANTING 1.0 INTRODUCTION The University of Reading has many rare and historic trees and is conscious of its duty to ensure the continuing amenity and environmental value of the campus. This can only be achieved by the appropriate selection of species and planting to the highest standards. The Grounds Maintenance Section is well aware of the potential conflicts that trees can provoke, many of which can be avoided by giving careful consideration to the species selected and the sites that they are planted. This aims to give practical advice, guidance and references to all those involved with tree planting on University property, with the aim of: • Preventing damage to University property or services • Reducing the need for future maintenance • Reducing future hazards 2.0 SELECTION OF SPECIES This guide does not intend to discuss the amenity value of tree species, as there are already many books on the subject but does hope to highlight considerations that should be made to ensure the most suitable species are selected for the site. 2.1 TOXICITY There are a number of tree species that are toxic if ingested or their sap can cause contact allergic reactions to skin and eyes. The likelihood of serious poisoning occurring is extremely unlikely because trees are generally unpalatable and are unlikely to be eaten in large quantities. Site assessment should be carried out before known toxic species are chosen. Species Common Name Toxic Hazard Aesculus sp. Chestnut Ingested fruits Ilex sp. Holly Ingested fruits Laburnum sp. Golden Rain Ingested seeds Ligustrum lucidum Chinese Privet Ingested fruits Rhus sp.