Substantial and Sustained Reduction in Under-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water, Sanitation, Hygiene & Health Studies Project

LIBRARY INTERNATIONAL REFERENCE CtNTTO FOF? COMMUNITY WATER 8UPPLX AN» !f*N (IRC) WATER, SANITATION, HYGIENE & HEALTH STUDIES PROJECT Aga Khan Health Service Northern Areas & Chitral Fourth Progress Report January to December 1994 WATER, SANITATION, HYGIENE & HEALTH STUDIES PROJECT Aga Khan Health Service Northern Areas & Chitral Fourth Progress Report January to December 1994 LIBRARY !NTS-?MATiONAL REFERENCE CFNTRn: FOR rCr/iWUNSlY WATER SUPPLY AND SA: iilATiGN (IRC') P.O. Boy •.3?-J!0, 2509 AD The Hagu« $ Toi. (070) 814911 ext 141/142 -** LO: p s\ INTRODUCTION FOREWORD This report covers the period January to December 1994 which is the first complete operational year for the WSHHS Project. During the first part of the year considerable time was spent by the Director and senior staff, on preparing a revised proposal and budget for combining additional research activities in the field of community water treatment - see section 1. Two other unexpected developments requiring the attention of the Director and the senior staff, have been the rural water supply and sanitation (RWSS) component of the Social Action Programme (SAP) - see section 3, and a collaborative project with the International Water and Sanitation Centre (IRC) on the role of communities in the management of improved rural water supplies - see section 4a. Rather than attempt to summarize here the many activities described on the following pages, a few important characteristics of the studies will be mentioned. Firstly is the practical nature of the research which has already resulted in the application of some of the findings in the programmes of LBRDD, AKRSP and AKHSP. Secondly is the amount of effort that has been given to listening to the views and ideas of women, especially concerning sanitation and hygiene issues. -

Role of Small Business Firms in Women Economic Empowerment: a Case Study of Gilgit Baltistan

International Journal of Academic Research in Economics and Management Sciences Nov 2014, Vol. 3, No. 6 ISSN: 2226-3624 Role of Small Business Firms in Women Economic Empowerment: A Case Study of Gilgit Baltistan Amjad Ali Lecturer Economics Karakoram International University, Gilgit Baltistan Email: [email protected] Shabana Mumtaz Student of MSc Economics Karakorum International University, Gilgit Baltistan Naila Akhtar Lecturer Economics Karakoram International University, Gilgit Baltistan Email: [email protected] Asif Sana Ullah Lecturer, Department of Business Management Karakoram International University, Gilgit Baltistan DOI: 10.6007/IJAREMS/v3-i6/1278 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJAREMS/v3-i6/1278 ABSTRACT This study is concerned with the role of small business firms in women economic empowerment in Gilgit Baltistan. The research design is a survey research using both qualitative and quantitative tools. Tabulation, frequency and percentages are the main tools used in Quantitative procedures while qualitative procedure includes the identification and comparison of different responses. Chi-Square test is also applied to test the hypothesis, developed in this study. The simple random sampling technique has been used to select respondents from 6 different small business firms and a sample of 200 female workers has been selected. The results showed that 65.12% female workers have been empowered economically due to small business firms. 66.28% respondents responded that firms have increased their decision making power on modification, repair and construction of a house and 61.63% responded that they take decisions on sale and purchase of livestock. The results further reveal that 80.23% said that they can take decision on transition of household equipment and 69.77% said that they can take decision on issues of children education. -

Excise and Taxation Department

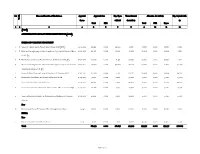

S.# Name and Location of The Scheme Approval Approved Cost Exp. Up to Throw-forward Allocation for 2018-19 Exp. Beyond 2018- T. Sch Status 06/2018 for 2018-19 19 Total FEC Total FEC Rupee 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 (Part-I) ADMINISTRATION AND LAW ENFORCEMENT SECTOR (A&LE) EXCISE AND TAXATION DEPARTMENT 1 T Const. of 4 Excise Check Posts at Entry Points of GB (R/M). 12-11-2015 30.312 0.000 29.624 0.688 0.688 0.000 0.688 0.000 2 T Estb. and Strengthening of Zakat Complex at Gilgit and Six District Offices 21-06-2016 98.467 0.000 51.838 46.629 46.629 0.000 46.629 0.000 in GB. (R) 3 T Establishment of District Excise Offices in All Districts of GB. (R) 21-06-2016 107.931 0.000 81.211 26.720 26.720 0.000 26.720 0.000 4 Motor Vehicle Registration and Taxation Management System for Excise & 21-09-2017 100.830 0.000 40.066 60.764 10.000 0.000 10.000 50.764 Taxation Department GB. (R) 5 Const. Of Ware Houses of Excise & Taxation in 3 Divisions of GB. 01-03-2017 165.703 0.000 55.416 110.287 20.000 0.000 20.000 90.287 6 Monitoring, Surveillance and Control of Narcotics in GB. 27-09-2017 50.000 0.000 0.000 50.000 5.000 0.000 5.000 45.000 7 Const. of Police Stations in 03 Districts. -

Male / Co-Education) and Male Head of Institution at Ssc Level Upto 14-07-2021

LIST OF AFFILIATED INSTITUTIONS WITH STATUS (MALE / CO-EDUCATION) AND MALE HEAD OF INSTITUTION AT SSC LEVEL UPTO 14-07-2021 Inst Inst Principal S.No Inst Adress Gender Principal Name Phone No Principal Mobile No level Code Gender Angelique School, St.No.81, Embassy 051-2831007-8, 1. SSC 1002 Co-Education Maj (R) Nomaan Khan MALE 0321-5007177 Road, G-6/4, Islamabad 0321-5007177 Sultana Foundation Boys High School, 2. SSC 1042 Farash Town, Lehtrar Road (F.A), MALE WASEEM IRSHAD MALE 051-2618201 (Ext 152) 0315-7299977 Islamabad Scientific Model School, 25-26, Humak 051-4491188 , 3. SSC 1051 Co-Education KHAWAJA BASHIR AHMAD MALE 0345-5366348 (F.A), Islamabad 0345-5366348 Fauji Foundation Model School, Chak Wing Cdre Muhammad Laeeq 051-2321214, 4. SSC 1067 Co-Education MALE 0320-5635441 Shahzad Campus (F.A), Islamabad. Akhtar 0321-4044282 Academy of Secondary Education, Nai 051-4611613, 5. SSC 1070 Abadi G.T Road, Rewat (F.A), Co-Education Mr. AZHAR ALI SHAH MALE 0314-5136657 0314-5136657 Islamabad National Public Secondary School, G. 051-4612166, 6. SSC 1077 Co-Education IRFAN MAHMOOD MALE 03005338499 T Road, Rewat (F.A), Islamabad 0300-5338499 National Special Education Centre for 9260858, 7. SSC 1080 Physically Handicapped Children, G- Co-Education Islam Raziq MALE 0333-0732141 9263253 8/4, Islamabad Oxford High School, 413, Street No 43, 8. SSC 1083 Co-Education Lt. Col. Zafar Iqbal Malik (Retd) MALE 051-2253646 0321-5010789 Sector G-9/1, Islamabad Rawat Residential College, college 9. SSC 1090 Co-Education Tanzeela Malik Awan MALE 051-2516381 03465296351 Road, Rawat (F.A), Islamabad Sir Syed Ideal School System, House 10. -

Page 1 of 5 SECTOR WISE SUMMARY of ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM ADP 2021-22 (Rs

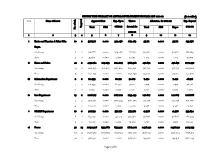

SECTOR WISE SUMMARY OF ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM ADP 2021-22 (Rs. in million) S.No Name of Sector Approved Cost Exp. Up to Throw- Allocation for 2021-22 Exp. Beyond Targeted Total FEC 06/2021 forward for Total FEC Rupee 2021-22 No. of sch. 2021-22 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 i Excise and Taxation & Zakat Ushr 10 2 598.527 0.000 329.058 269.469 35.711 0.000 35.711 233.758 Deptt. On-Going 8 2 546.877 0.000 329.058 217.819 30.970 0.000 30.970 186.849 New 2 0 51.650 0.000 0.000 51.650 4.741 0.000 4.741 46.909 ii Home and Police 42 2 4477.784 245.035 1214.203 3263.581 492.651 0.000 492.651 2770.930 On-Going 33 2 3225.535 245.035 1214.203 2011.332 397.730 0.000 397.730 1613.602 New 9 0 1252.249 0.000 0.000 1252.249 94.921 0.000 94.921 1157.328 iii Information Department 2 0 114.933 0.000 60.921 54.012 7.494 0.000 7.494 46.518 On-Going 2 0 114.933 0.000 60.921 54.012 7.494 0.000 7.494 46.518 New 0 0 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 iv Law Department 15 2 2226.717 0.000 1067.222 1159.495 142.607 0.000 142.607 1016.888 On-Going 11 2 2101.717 0.000 1067.222 1034.495 133.459 0.000 133.459 901.036 New 4 0 125.000 0.000 0.000 125.000 9.148 0.000 9.148 115.852 v S&GAD Department 10 0 927.132 0.000 551.770 375.362 41.528 0.000 41.528 333.834 On-Going 8 0 857.132 0.000 551.770 305.362 36.868 0.000 36.868 268.494 New 2 0 70.000 0.000 0.000 70.000 4.660 0.000 4.660 65.340 vi Power 97 23 20154.928 1733.662 8313.521 11841.407 2436.252 0.000 2436.252 9405.155 On-Going 63 23 16187.957 1733.662 8313.521 7874.436 2136.334 0.000 2136.334 5738.102 New 34 0 3966.971 0.000 0.000 3966.971 299.918 0.000 299.918 3667.053 Page 1 of 5 SECTOR WISE SUMMARY OF ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM ADP 2021-22 (Rs. -

Pakistan Occupied Kashmir: Changing the Discourse

Pakistan Occupied Kashmir : Changing the Discourse t t t t r r c c e e j j o o o o r r P P K K p p o o P P e e R R MAY 2011 IDSA PoK Project Report May 2011 PAKISTAN OCCUPIED KASHMIR: CHANGING THE DISCOURSE Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses New Delhi Ó Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 81-86019-90-1 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Report are those of the Project Team and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses or the Government of India. First Published: May 2011 Price: Rs. 175/- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Cover & Layout by: Geeta Kumari Printed at: M/s A. M. Offsetters A-57, Sector-10, Noida-201 301 (U.P.) Mob.: 09810888667 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................5 Abbreviations.......................................................................................................7 Brief Background................................................................................................9 -

I Northern Areas

I Northern Areas Strategic Provincial Investment Plan and Project Preparation for Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Health. 8 2 2 P K N 0 8 9 Final Strategic Investment Plan VOL. I Warclrop - Acres Cowater International September, 1989 NESPAK. Northern Areas Strategic Provincial Investment Plan and Project Preparation for Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Health. Final Strategic Investment Plan VOL. I ~LIBRARY~ , iNTERNAriOV.'M. ;i.;-~Ft:RtNCf£ Wardrop - Acres Cowater International September, 1989 NESPAK. I I I I I I I NORTHERN AREAS Strategic Provincial Investment Plan I and Project Preparation for I Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Health I Prepared for the World Bank under sub-contract to I Wardrop-Acres Consultants September 1989 I I I I DRMS Development Research and Management Services (Pvt.) Limited I 40-A Kaghan Road, F-8/4 Tel: (92-51) 852863 P.O. Box 2389 Fax: (92-51 ) 822313 Islamabad Tlx: 5»l1 NAIBA PK I Pakistan 5945 CTOIB PK I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I Page No. List of Tables vi I List of Figures vii g List of Abbreviations ix I Executive Summary x • 1 . INTRODUCTION 1 • 1.1. Introduction to the Project 1 1.2. Introduction to the Northern Areas 2 I 2 . THE SECTOR 6 I 2.1. General 6 1. The Physical Setting 6 | 2. Social and Institutional Setting 10 3. The Farm-Household 12 m 4. Demographic Background and Settlement Patterns 13 I 5. Administrative Arrangements 13 2.2. Sector Institutions 14 I 1. Scope of Description and Analysis 14 2. Local Government Institutions 16 • 3. -

Vice Chancellor's R Eport

(June 2018 - June 2020) Karakoram International University Vice Chancellor’s Report GILGIT - BALTISTAN www.kiu.edu.pk VISION The Karakoram International University endeavors to become a leading institution of higher learning, meaningfully contributing to sustainable development, promoting knowledge economies and pluralistic societies in the mountainous regions of Pakistan and geographically similar landscapes elsewhere. MISSION Ÿ Offering Quality academic programs in line with the local, regional & global demands Ÿ Attracting & nurturing high-quality minds to address the contemporary challenges through dissemination & generation of high-quality knowledge & cutting edge research Ÿ Promoting & conserving the indigenous values and creating social & ethical responsibility Ÿ Trying to become nancially sustainable; through commercialization of Research and Development. VALUES The University is committed to uphold and promote: Ÿ Excellence and quality in all its functions including scholarship in its broader aspects, careful management, and ethical considerations. Ÿ Acceptance of diversity and pluralism, with particular regard to gender, race, color, beliefs, culture, and religion. Ÿ Holistic development of its students, faculty, and staff as managers and critical users of knowledge and human resource. Ÿ A culture of inquiry, creativity, critical thinking, and the free exchange of thoughts. Ÿ The relevance of its functions to the goals of development of individuals, society, and environment at the regional and global levels. Ÿ Provision of efcient and effective relevant services to all internal and external stakeholder. STRATEGY Ÿ Recruit and retain highly qualied faculty who are committed to deliver the expectations outlined in the vision and mission. Ÿ Ensure merit and quality in the admission of students. Ÿ Develop and deliver knowledge content that is relevant to the local context; that capitalizes on local comparative advantages. -

Prevalence and Antibiogram of Uncomplicated Lower Urinary Tract Infections in Human Population of Gilgit, Northern Areas of Pakistan

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 40(4), pp. 295-301, 2008. Prevalence and Antibiogram of Uncomplicated Lower Urinary Tract Infections in Human Population of Gilgit, Northern Areas of Pakistan KHALIL AHMED AND IMRAN Department of Biological Sciences, Karakoram International University, Gilgit, Northern Areas, Pakistan e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.- A study was conducted during April, 2006 to March 31, 2007 to investigate the prevalence and antibiogram of urinary tract infections in human population of Gilgit, Northern Areas of Pakistan. Two hundred and fifty eight urine specimens of lower urinary tract infected patients referred to District Headquarter Hospital, Gilgit for bacteriological investigation, were cultured on Cystine Lactose Electrolyte-Deficient (CLED) agar (Oxoid) with the help of celebrated sterilized loop urine (approximately 0.01 ml) and incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24 hours. More than 10 Gram staining. The Gram positive organisms were identified by coagulase, catalase and DNase tests, whereas Gram negative strains were identified by various biochemical tests. Out of 258 urine specimens, 113 (43.80%) were found infected with the pathogenic bacteria. The commonest isolates were Escherichia coli 55 (48.67%), Staphylococcus saprophyticus 34 (30.1%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa 8 (7.2%), Proteus vulgaris 5 (4.43%), Proteus mirabilis 2 (1.77%), Proteus sp. 3 (2.66%), Pseudomonas sp. 1 (0.3%) and Staphylococcus sp. 3 (2.66%). The incidence of urinary tract infection was high in females 68 (60.18%) as compared to males 45 (39.83%) and in the age group 21-50 years. The highest prevalence was found in Magini Muhala, Basin, Kashrote, Amphary and very few from Nagaral and Jutial. -

Substantial and Sustained Reduction in Under-5 Mortality, Diarrhea, And

eCommons@AKU Community Health Sciences Department of Community Health Sciences 5-24-2020 Substantial and sustained reduction in under-5 mortality, diarrhea, and pneumonia in Oshikhandass, Pakistan: Evidence from two longitudinal cohort studies 15 years apart C L. Hansen National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA. B J J. McCormick National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA. Iqbal Azam Syed Aga Khan University, [email protected] K Ahmed Karakoram International University, University Road, Gilgit, Pakistan J M. Baker National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA. See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_chs_chs Part of the Community Health and Preventive Medicine Commons, and the Maternal and Child Health Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, C. L., McCormick, B. J., Syed, I. A., Ahmed, K., Baker, J. M., Hussain, E., Jahan, A., Jamison, A. F., Samji, N., Oshikhandass Diarrhea and Pneumonia Project, ., Zaidi, A., Jan, A. (2020). Substantial and sustained reduction in under-5 mortality, diarrhea, and pneumonia in Oshikhandass, Pakistan: Evidence from two longitudinal cohort studies 15 years apart. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 759. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_chs_chs/760 Authors C L. Hansen, B J J. McCormick, Iqbal Azam Syed, K Ahmed, J M. Baker, E Hussain, A Jahan, A F. Jamison, N Samji, Oshikhandass Diarrhea and Pneumonia Project, Anita K. M. Zaidi, and Ahmed Jan This article is available at eCommons@AKU: https://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_chs_chs/760 Hansen et al. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:759 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08847-7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Substantial and sustained reduction in under-5 mortality, diarrhea, and pneumonia in Oshikhandass, Pakistan: evidence from two longitudinal cohort studies 15 years apart C. -

Risk Assessment by Bacteriological Evaluation of Drinking Water of Gilgit-Baltistan

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 44(2), pp. 427-432, 2012. Risk Assessment by Bacteriological Evaluation of Drinking Water of Gilgit-Baltistan Khalil Ahmed,1 * Mushtaq Ahmed,2 Javaid Ahmed2 and Akbar Khan1 1Department of Biological Sciences, Karakoram International University, Gilgit-Baltistan, 2Aga Khan Planning and Building Service Pakistan, Abstract.- In Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan glaciers are the main source of water and people use surface water from nallahs (big streams) and springs for both drinking and irrigation purposes. The surface water has many chances of water borne diseases. From out of seven districts the drinking water samples of four districts were bacteriolocically analyzed for fecal coliform contamination. Randomly selected 46 villages and their water samples were analyzed at different points by using membrane filtration technique and specific medium (lauryl sulphate broth). It was found that 25 villages use water from the springs and fecal coliform contamination was from 0 - 500 cfu in 100 ml water at source, from 0 - TNTC in the beginning, mid and at the end of the distribution system. Twenty one villages use water from the nallahs and fecal coliform contamination was from 4 – 500 cfu at the source, 1 -1350 cfu in the beginning of the distribution system, 44 - TNTC in the middle and 110 - TNTC in the end of the distribution system. In most of the springs the bacteriological quality of drinking water was good at source and it becomes contaminated as it becomes in contact with animals. Most of the nallahs water was contaminated at their source. Key words: Drinking water, analysis of fecal coliform of water, bacteriological analysis of water, water quality, microbiological quality of water of Gilgit-Baltistan. -

Genigraphics Research Poster Template 42X72

1484 Contact: Detection of Respiratory Syncytial (RSV) and Influenza Viruses in Children with WHO Defined Pneumonia and Controls from Oshikhandass Village, Gilgit-Baltistan, Northern Pakistan from 2012-2014; Sensitivity and Specificity of Rapid Tests vs. PCR Zeba Rasmussen, MD, MPH Fogarty International Center National Institutes of Health Zeba A. Rasmussen1, Julia M. Baker1, Assis Jahan1, Uzma Bashir Aamir3, Fatima Aziz2, Shahida M. Qureshi2, Syed Iqbal Azam4, Syed Sohail Zahoor Zaidi3, Khalil Ahmed5, Cecile Viboud1, Stacey Knobler1 16 Center Drive, Building 16 Bethesda, MD 20892 1National Institutes of Health, Fogarty International Center, Division of International Epidemiology and Population Studies, 2Aga Khan University, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, 3National Institute Phone: (301) 496-0815 of Health, Islamabad, Department of Virology, 4Aga Khan University, Department of Community Health Sciences, 5Karakoram International University, Department of Biological Sciences Email: [email protected] QuickVue & Luminex Sofia & PCR (Luminex+Taqman) Conclusions Methods and Materials N = 60 N = 186+42=228 Sensitivity for influenza was substantially Female health workers trained in pneumonia management Sens(± 2*SD) Spec(± 2*SD) Sens (± 2*SD) Spec(± 2*SD) lower than previously reported3,4. Possible using WHO Integrated Management of Childhood Illness 0% 100%(+ 0) 50% (+ 69) 94% (+ 3) reasons for poor sensitivity include low (IMCI) guidelines2 conducted weekly surveillance of children Inf A 0/6 53/53 1/2 206/218 influenza circulation in the community and under age 5 years. Each episode was classified by severity, modest sample size. Other factors may be based on WHO guidelines, treatment was given and referral N/A 100%(+ 0) 100%(+ 0) 91%(+ 4) Inf B the inability to maintain controlled done, if needed.