Virtual Democracy in Thailand: -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C NTENT 2018 L

28 May-10 june C NTENT 2018 www.contentasia.tv l www.contentasiasummit.com Discovery takes StarHub carriage row to Singapore viewers 11 channels in danger as renewal talks deadlock, new StarHub head Peter K could arrive on 9 July to a smouldering TV mess Discovery took its carriage renewal negotiations public this morning in an aggressive campaign designed to whip up public support for its channels in Sin- gapore – and (clearly) to pressure local platform StarHub into softening its current stand against the renewal of an 11-chan- nel bundle. As of today, seven Discovery channels are scheduled to go dark on 30 June, with the newly acquired four-channel Scripps bouquet headed into the abyss at the end of August. Discovery says it has already been for- mally notified by StarHub that its channels are not being renewed. In a response this morning, StarHub didn’t mention any formal notice, saying only that “we are in renewal negotia- tions... and we are doing everything pos- sible to arrive at a deal which would allow Discovery and StarHub to continue our partnership while offering our customers the same content at a reasonable price”. StarHub isn’t coming into this public fight with no firepower, saying it is acquiring fresh content to replace Discovery “in the event that negotiations prove unsuc- cessful”. Several new channels are in the works “to ensure our customers will continue to enjoy access to a good range of educa- tion and lifestyle channels,” StarHub says. Read on: page 2 C NTENTASIA 28 May-10 june 2018 Page 2. -

Thailand in View a CASBAA Market Research Report

Thailand in View A CASBAA Market Research Report Executive Summary 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Pay-TV environment market competition from satellite TV, and perceived unfair treatment by the National Broadcasting and The subscription TV market experienced a downturn Telecommunications Commission, whose very broad in 2014 as a result of twin events happening almost “must carry” rule created a large cost burden on simultaneously: the launch of DTT broadcasting in operators (particularly those that still broadcast on an April 2014 increased the number of free terrestrial TV analogue platform). stations from six to 24 commercial and four public TV broadcasters, leading to more intense competition; and Based on interviews with industry leaders, we estimate the military takeover in May 2014 both created economic that in 2015 the overall pay-TV market contracted by uncertainty and meant government control and three percent with an estimated value of around US$465 censorship of the media, prohibiting all media platforms million compared to US$480 million the previous from publishing or broadcasting information critical of year. Despite the difficult environment, TrueVisions, the military’s actions. the market leader, posted a six percent increase in revenue year-on-year. The company maintained its The ripple effects of 2014’s events continue to be felt by leading position by offering a wide variety of local and the industry two years after. By 2015/2016, the number of international quality content as well as strengthening licensed cable TV operators had decreased from about its mass-market strategy to introduce competitive 350 to 250 because of the sluggish economy, which convergence campaigns, bundling TV with other suppressed consumer demand and purchasing power, products and services within True Group. -

APA Format 6Th Edition Template

Proceedings of the 4th World Conference on Media and Mass Communication, Vol. 4, Issue 2, 2018, pp. 58-65 Copyright © 2018 TIIKM ISSN 2424-6778 online DOI: https://doi.org/10.17501/24246778.2018.4206 THE INTERNATIONAL TRADE OF TELEVISION PROGRAMS IN THAILAND IN THE AGE OF DISRUPTIVE TECHNOLOGY Sudthanom Rodsawang* Dhurakij pundit University, Thailand Abstract: This article studied the evolution and characteristics of the international trade of TV programs in Thailand as a guideline for TV station executives and TV program producers to identify an opportunity to develop their media business amidst the changing technology and audience behavior in the age of disruptive technology. The research methods included documentary analyses and interviews with mass media scholars, TV station executives, and advertising agency representatives. Most of the popular TV programs at present are copyright shows purchased from overseas, in the forms of purchases of the copyrights of finished programs as well as the copyrights of format programs; most of which were game shows, reality shows, and drama series. The characteristics of the international trade of the TV programs in Thailand included (1) trade of TV programs in the content market, (2) exchanges of TV programs between Thai and international TV stations for broadcasting, and (3) international co-productions of TV programs. Three factors that influenced TV stations in Thailand to purchase foreign TV programs were (1) changes in technology, (2) changes in consumer behavior, and (3) business survival. Therefore, the international trade of TV programs is another solution for TV stations and TV program producers in Thailand to reduce production costs, increase revenues, and expand the audience base worldwide. -

Viu Thailand Announces New Collaborations with Channel 3 And

Viu Thailand announces new collaborations with Channel 3 and Amarin TV Together with GMMTV and CHANGE2561 bringing more top-notch Thai entertainment for Viu-ers across Asia PCCW (SEHK: 0008) – HONG KONG / THAILAND, June 1, 2021 – Viu, PCCW’s leading pan-regional OTT video streaming service, joins hands with leading Thailand entertainment players, Channel 3 and Amarin TV, to serve up highly-anticipated Thai contents to Viu-ers across Asia including Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, and the Philippines. Adding to Viu’s existing content partnerships with GMMTV and CHANGE2561, Viu continues to collaborate with leading content providers to grow its ecosystem, bringing exceptional Thai contents and talents to the regional spotlight. Asian Viu-ers can enjoy their favorite Thai shows, from melodramas, intense dramas, romantic comedies, variety shows, and many more on Viu. Thai Viu-ers can enjoy four top dramas from Channel 3, exclusively within two hours after the initial broadcast, including the first exclusive romantic comedy series, PraoMook (May 2021), which was filmed in South Korea, starring Pon-Nawasch Phupantachsee and Bua- Nalinthip Sakulongumpai, and other series to come. Over 600 hours of dramas from Channel 3 will also be available for Viu-ers to watch at their leisure. Furthermore, the new collaboration will make Viu the first OTT video streaming platform to offer Amarin TV’s simulcast content. Viu-ers can enjoy popular series such as The Folly of Human Ambition, Cheating Spouse, and more, all with a 30-day exclusive head-start*. The strong partnership with GMMTV has entertained Viu-ers with a myriad of contents, including upcoming series Irresistible, The Player, The War of Flowers, and many more which will be exclusively available to Viu-ers in selected markets** Viu operates in. -

Implementing Digital TERRESTRIAL TELEVISION in THAILAND Report

THAILAND JUNE JUNE 2015 Implementing digital TERRESTRIAL TELEVISION IN THAILAND Report ISBN 978-92-61-16061-6 9 7 8 9 2 6 1 1 6 0 6 1 6 IMPLEMENTING TERRESTRIAL TELEVISION DIGITAL IN THAILAND Telecommunication Development Sector Implementing digital terrestrial television in Thailand This report has been prepared by International Telecommunication Union (ITU) expert Peter Walop. The work on this report was carried out in the framework of a joint effort between ITU and the National Broadcasting and Telecommunication Commission (NBTC) of Thailand on the implementation of digital terrestrial television broadcasting (DTTB). ITU would like to thank the NBTC for their valuable input and support, as well as the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (MSIP), Republic of Korea in facilitating ITU for the implementation of the transition from analogue to digital terrestrial television broadcasting case study in Thailand. Please consider the environment before printing this report. ITU 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. Implementing digital terrestrial television in Thailand Table of contents Page 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 2 Television market in Thailand ............................................................................................ 4 2.1 Market structure .............................................................................................................. -

2010 Annual Language Service Review Briefing Book

Broadcasting Board of Governors 2010 Annual Language Service Review Briefing Book Broadcasting Board of Governors Table of Contents Acknowledgments............................................................................................................................................................................................3 Preface ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................5 How to Use This Book .................................................................................................................................................................................6 Albanian .................................................................................................................................................................................................................12 Albanian to Kosovo ......................................................................................................................................................................................14 Arabic .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................16 Armenian ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................20 -

The Creation of Thai Public Broadcasting Service: Thailand’S First Public Television Station

June 2008 TDRI Quarterly Review 3 The Creation of Thai Public Broadcasting Service: Thailand’s First Public Television Station Somkiat Tangkitvanich* 1. THE TELEVISION LANDSCAPE IN of the Army, Channel 9 of the Mass Communication THAILAND Organization of Thailand (MCOT), and Channel 11 of the Government Public Relations Department (PRD). Television is the most powerful medium in Thailand, Privately run State-owned stations are Channel 3 followed by radio. The reason why the electronic media (operated through a concession granted by MCOT), are far more popular than newspapers and other forms of Channel 7 (operated through a concession granted by the print media is related to the country’s low average level Army), and iTV (operated through a concession of education. A survey by AcNielsen, a media market granted by the Office of the Prime Minister. A new research firm, showed that about 86 percent of the Thai regulatory model based on a licensing system was about population watch television every day, while 36 and 21 to be introduced around 2000 but was delayed for over percent listen to the radio and read newspapers, seven years owing to legal disputes concerning the respectively (Table 1). Thus, television plays a very selection of its regulator, the National Broadcasting significant role in providing the people with news and Commission (NBC). information, and is influential in shaping their political All privately run television stations are majority- and social views. The influence of television is more owned by their founders’ families. For example, prominent in the rural areas of the country where the rate Channel 3 is operated by a company owned by the of newspaper readership is only 14 percent. -

Spectrum for Television Broadcasting and 700Mhz

สํานักงานคณะกรรมการกิจการกระจายเสียง กิจการโทรทัศน และกิจการโทรคมนาคม (สํานักงาน กสทช.) Office of the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) Spectrum for Television Broadcasting and IMT 700 MHz in Thailand Supatrasit Suansook 21 August 2017 Broadcasting Technology and Engineering Bureau Office of the NBTC facebook : Broadcast.Engineering.NBTC Topics Digital Terrestrial Television in Thailand : Overview Frequency Planning and Frequency Utilization for Analogue and Digital Terrestrial Television in Thailand Steps to Release 470 MHz for Digital TV and 700 MHz for IMT in Thailand Challenges Supatrasit Suansook (Office of the NBTC, Thailand) Page 2 หนาที่ 2 Digital Terrestrial Television in Thailand: Overview Supatrasit Suansook (Office of the NBTC, Thailand) Page 3 Current Digital TV Networks 4 Network Operators operating 5 Digital TV Networks 1 Network = 1 Multiplex = Using 1 Radio Frequency per area Supatrasit Suansook (Office of the NBTC, Thailand) Page 4 หนาที่ Current Status of Multiplexes and TV Programs Current: 26 TV Program being broadcasted in DTT Platform (by 5 MUXs) as of March 2016 • 22 Commercial Programs * • 4 Public Programs Target: 48 TV Program (6 MUXs) • 24 Commercial Programs • 12 Public Programs • 12 Community Programs * 2 Commercial Program Licenses were withdrawn. Supatrasit Suansook (Office of the NBTC, Thailand) Page 5 หนาที่ Digital TV Coverage and Rollout Plan Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 4 (Apr’13 – Jun’14) (Jun’14 – Jun’15) (Jun’15 – Jun’16) (Jun’16 – Jun’17) 50% 80% 90% 95% 168 sites -

View / Download the Full Paper in a New

A Study of Cultural Transmission Through Thai Television Drama Sanpach Jiarananon, Bansomdejchaopraya Rajabhat University, Thailand The IAFOR International Conference on the City 2017 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This research entitled “A Study of Cultural Transmission Through Thai Television Drama” were 1) to study a policy of drama television producers on transmitting content of Thai cultures through television drama and 2) to study content of television drama presenting Thai cultures. The result revealed that the majority of producers’ policies have been focused on target audiences by producing Thai history-based drama with the addition of Thai cultures in order to make themselves outstanding. Thai identity was presented through each television drama based on its plot which had been selected since pre-production process. Moreover, Thai ways of life was also perfectly integrated together with the presentation of lessons learned based on Thai cultures. The contents presented were to remind audiences of human mind, family life and ways of living which were considered as contemporary cultures rather than authentic Thai cultures. Keywords: Cultural Transmission, Thai Culture, Television Drama iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Introduction Nowadays, television media plays very important role in society, television media is one kind of approachable media to the audiences because it became very important thing in living factor of people. It’s evident that every home has 1-2 televisions at least and interesting of television a media both attractive audio and video or excitement made audiences impress and keep follow up contents offered through television media and abide by their value in sometimes. -

The Creation of Thai Public Broadcasting Service: Thailand's

June 2008 TDRI Quarterly Review 3 The Creation of Thai Public Broadcasting Service: Thailand’s First Public Television Station Somkiat Tangkitvanich* 1. THE TELEVISION LANDSCAPE IN of the Army, Channel 9 of the Mass Communication THAILAND Organization of Thailand (MCOT), and Channel 11 of the Government Public Relations Department (PRD). Television is the most powerful medium in Thailand, Privately run State-owned stations are Channel 3 followed by radio. The reason why the electronic media (operated through a concession granted by MCOT), are far more popular than newspapers and other forms of Channel 7 (operated through a concession granted by the print media is related to the country’s low average level Army), and iTV (operated through a concession of education. A survey by AcNielsen, a media market granted by the Office of the Prime Minister. A new research firm, showed that about 86 percent of the Thai regulatory model based on a licensing system was about population watch television every day, while 36 and 21 to be introduced around 2000 but was delayed for over percent listen to the radio and read newspapers, seven years owing to legal disputes concerning the respectively (Table 1). Thus, television plays a very selection of its regulator, the National Broadcasting significant role in providing the people with news and Commission (NBC). information, and is influential in shaping their political All privately run television stations are majority- and social views. The influence of television is more owned by their founders’ families. For example, prominent in the rural areas of the country where the rate Channel 3 is operated by a company owned by the of newspaper readership is only 14 percent. -

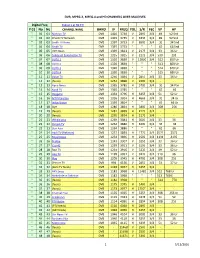

FTA Digital Channels Frequency List

DVB, MPEG-2, MPEG-4 and HD CHANNELS OVER MALDIVES. Digital Freq Paksat 1 at 38.0°E P 01 No No CHANNEL NAME BAND IF FREQ POL S/R FEC VP AP " 01 01 Mehran TV DVB 1420 3730 V 2890 3/4 49 52 Snd " 02 02 Dharti TV Network DVB 1415 3735 V 3333 3/4 49 52 Snd " 03 03 Sindh TV News DVB 1397 3753 V 6500 3/4 33 34 Snd " 04 04 Sindh TV DVB 1397 3753 " " " 65 66 Snd " 05 05 VSH News DVB 1339 3811 V 2175 3/4 33 36 Ur " 06 06 Sabzbaat Balochistan TV DVB 1335 3815 V 2222 3/4 530 291 " 07 07 VUTV 1 DVB 1320 3830 V 12000 3/4 512 650 Ur " 08 08 VUTV 2 DVB 1320 3830 " " " 513 660 Ur " 09 09 VUTV 3 DVB 1320 3830 " " " 514 670 Ur " 10 10 VUTV 4 DVB 1320 3830 " " " 515 680 Ur " 11 11 Value TV DVB 1256 3894 V 2850 3/4 33 36 Ur " 12 12 (feeds) DVB 1252 3898 V 2200 3/4 - - " 13 13 Apna News DVB 1365 3785 H 5700 3/4 33 34 Pan " 14 14 Kook TV DVB 1365 3785 " " " 65 66 " 15 15 Oxygene DVB 1354 3796 H 3255 3/4 51 52 Ur " 16 16 MTV Pakistan DVB 1336 3814 H 4666 3/4 33 34 Ur " 17 17 Indus Vision DVB 1336 3814 " " " 65 66 Ur " 18 18 Oye DVB 1286 3864 H 3800 3/4 308 256 " 19 19 (feeds) DVB 1281 3869 H 2170 3/4 - - " 20 20 (feeds) DVB 1276 3874 H 2170 3/4 - - " 21 21 Wikkid plus DVB 1269 3881 H 3000 3/4 33 36 " 22 22 Punjab TV DVB 1264 3886 H 6200 3/4 33 34 " 23 23 Star Asia DVB 1264 3886 " " " 65 66 " 24 24 Hadi TV (Pakistan) DVB 1257 3893 H 1770 3/4 2571 2572 " 25 25 Royal News DVB 1254 3896 H 2500 3/4 4194 4195 " 26 26 N-Vibe DVB 1243 3907 V 3255 3/4 33 36 Ur " 27 27 City 42 DVB 1239 3911 V 3100 3/4 33 36 Ur " 28 28 Ravi TV DVB 1234 3916 V 3333 3/4 49 52 Ur " 29 29 -

C NTENT 4-17 May 2020 L

C NTENT 4-17 May 2020 www.contentasia.tv l www.contentasiasummit.com JTBC drama busts Sky Castle record A World of Married Couple becomes Korea’s highest-rated cable drama JTBC drama A World of Married Couple broke cable ratings records this week- end, ending Sky Castle’s 15-month reign. With four episodes to go, the 16-episode prime-time Fri/Sat series hit nationwide ratings of 24.332% (AGB Nielsen) on Sat- urday (2 May). Sky Castle ended its run on 1 Feb 2019 with a high of 23.779%. A World of Married Couple is based on BBC drama Doctor Foster. The full story is on page 6 & 7 q Producers scramble after Hooq liquidation Production houses sit tight on Hooq Mauritius Producers across the region and rights holders around the world are holding a collective breath for the next move by Hooq Mauritius, which holds the bulk of the content/IP contracts signed for failed Asian streaming platform Hooq. Overwhelming sentiment is that the en- tity will follow the Singapore-registered Hooq Digital Pte Ltd into liquidation. But until it does, hope springs eternal. The full story is on page 5 q PLUS • Industry pays tribute to Tetsu Uemura • Free-flow TV for SG migrant workers • Top shows in Thailand and what’s most in demand in India... & a whole lot more. 4-17 May 2020 page 2. C NTENTASIA 4-17 MaY 2020 Page 3. Thai streaming mins up Free-flow TV for S’pore migrant workers 6% for April; Netflix tops Media co’s step in to entertain workers on lockdown mins, True ID tops MAUs Media companies across Singapore are sages from Hollywood and Bollywood Netflix was Thailand’s top VOD service in providing free entertainment to Singa- along with daily talk shows for workers April by streaming minutes, with second pore’s one-million strong community of on Radio Masti and projects with local place going to the Thai operation of migrant workers hit hard by Covid-19.