Peshastin Creek Watershed Field Trip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backcountry Campsites at Waptus Lake, Alpine Lakes Wilderness

BACKCOUNTRY CAMPSITES AT WAPTUS LAKE, ALPINE LAKES WILDERNESS, WASHINGTON: CHANGES IN SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION, IMPACTED AREAS, AND USE OVER TIME ___________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University ___________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Resource Management ___________________________________________________ by Darcy Lynn Batura May 2011 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Darcy Lynn Batura Candidate for the degree of Master of Science APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Karl Lillquist, Committee Chair ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Anthony Gabriel ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Thomas Cottrell ______________ _________________________________________ Resource Management Program Director ______________ _________________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii ABSTRACT BACKCOUNTRY CAMPSITES AT WAPTUS LAKE, ALPINE LAKES WILDERNESS, WASHINGTON: CHANGES IN SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION, IMPACTED AREAS, AND USE OVER TIME by Darcy Lynn Batura May 2011 The Wilderness Act was created to protect backcountry resources, however; the cumulative effects of recreational impacts are adversely affecting the biophysical resource elements. Waptus Lake is located in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, the most heavily used wilderness in Washington -

Blewett -Cle Elum Iron Ore Zone Chelan and Kittitas Counties, Washington

State of Washington ARTHUR B. LANGLIE, Govemor Department of Conservation and Development ED DAVIS , Director DIVISION OF GEOLOGY HAROLD E. CULVER, Supervisor Report of Investigations No. 12 ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF THE Blewett -Cle Elum Iron Ore Zone Chelan and Kittitas Counties, Washington By W. A. BROUGHTON O LYMPIA STATE ,.RINTING ..LANT For sale by Department of Conservation and Development, Olympia, Washington. Price, 25 cents. CONTENTS Page Foreword . 5 Introduction . 6 Mining operations . 7 Field work . • . 7 Acknowledgments . 8 Earlier investigations . 8 Geology ............................................................. 11 Character of the iron beds. 11 Analyses . 13 Iron deposits . 14 Blewett deposits . 15 (. Nigger Creek deposits ............... ....... .. .................. 16 Area 1 ................................. ...................... 16 Area 2 ....................................................... 17 Area 3 .................... .................................. 18 Stafford Creek deposits. 20 Area 1 ....................... .. .............................. 20 Area 2 ....................................................... 21 Bean Creek deposits. 23 Area 1 ........................ .............................. 23 Area 2 ....................................................... 24 Iron Peak deposits ............. ................................... 26 .Area 1 .... ......... ...... .................................. 26 Area 2 ......................................... ........... 28 Area 3 ................ .. .................................... -

Snow Lake Water Control Structure, Draft Environmental Assessment

Draft Environmental Assessment Snow Lake Water Control Structure Chelan County, Washington U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region Columbia Cascades Area Office Yakima, Washington October 2017 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian tribes and our commitments to island communities. MISSION OF THE BUREAU OF RECLAMATION The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Cover Photograph: Existing butterfly valve and valve support. Acronyms and Abbreviations CCT Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation Complex Leavenworth Fisheries Complex cfs cubic feet per second DAHP Washington Department of Archelogy and Historic Preservation dB decibel EA Environmental Assessment ESA Endangered Species Act IPID Icicle and Peshastin Irrigation Districts (IPID) ITAs Indian Trust Assets LNFH Leavenworth National Fish Hatchery NEPA National Environmental Policy Act NHPA National Historic Preservation Act NMFS National Marine Fisheries Service Reclamation Bureau of Reclamation USFS United States Forest Service USFWS United States Fish and Wildlife Service Wilderness Act Wilderness Act of 1964 Yakama Nation Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation This page intentionally left blank Table of Contents -

Teanaway Natural History

Teanaway Natural History Silat Mushtaque Original material by Cindy Luksus Photo by I by Photo Teanaway Natural History 1. Who were the first inhabitants? 2. What is the history of the land? 3. Geology of the area 4. Forest dynamics 5. Trees, shrubs, flowers, wildlife, butterflies, lichen Photo by Karen Wallace Karen by Photo Teanaway History • The first inhabitants of the Teanaway River Valley were members of the Yakama, Cayous and Nez Perce Indian Tribes. The Teanaway Valley was part of the summering grounds for these tribes. The name Teanaway possibly had its origins in a Sahaptin word, tyawnawí-ins, meaning “Drying Place”. • The watershed is within the ceded area of the Yakama Nation under the Treaty of 1855. Photo by Adam Johnson Teanaway History Farming, grazing, and timber harvest became important within the watershed as European immigrants and other settlers began moving into the area in the late 1800s. Sheep and livestock grazing occurred, and at various times, several thousand head of livestock grazed in the area. Timber harvest within the forest began early in the 1900s. Alpine Lakes Wilderness Alpine Lakes Wilderness Esmeralda Iron De Roux All areas in green are Okanagan/Wenatchee National Forest Bean Crk Teanaway Links: Where to read more about it! 1. Teanaway Magic from the WTA magazine: https://www.wta.org/news/magazine/magazine/1071.p df 2. Teanaway Community Forest Management Plan: http://www.friendsoftheteanaway.org/wp- content/uploads/amp_rec_TeanawayRecPlan_120718.p df Photo by I Padraic Ryan I Padraic by Photo Mt Stuart dominates the upper elevation views Bean Creek Basin Esmerelda Basin Swauk and Tronsen Ridge Iron Peak Geology • The geology of the area is dominated by the Late Jurassic/Early Cretaceous Ingalls Tectonic Complex. -

A World to Explore Six Months in Nine Days E X P L O R E • L E a R N

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG FALL 2017 • VOLUME 111 • NO. 4 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE in this issue: A World to Explore and a Community to Inspire Six Months in Nine Days Life as an Intense Basic Student tableofcontents Fall 2017 » Volume 111 » Number 4 Features The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy 26 A World to Explore the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. and a Community to Inspire 32 Six Months in Nine Days Life as an Intense Basic Student Columns 7 MEMBER HIGHLIGHT Craig Romano 8 BOARD ELECTIONS 2017 10 PEAK FITNESS Preventing Stiffness 16 11 MOUNTAIN LOVE Damien Scott and Dandelion Dilluvio-Scott 12 VOICES HEARD Urban Speed Hiking 14 BOOKMARKS Freedom 9: By Climbers, For Climbers 16 TRAIL TALK It's The People You Meet Along The Way 18 CONSERVATION CURRENTS 26 Senator Ranker Talks Public Lands 20 OUTSIDE INSIGHT Risk Assessment with Josh Cole 38 PHOTO CONTEST 2018 Winner 40 NATURES WAY Seabirds Abound in Puget Sound 42 RETRO REWIND Governor Evans and the Alpine Lakes Wilderness 44 GLOBAL ADVENTURES An Unexpected Adventure 54 LAST WORD Endurance 32 Discover The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the Mountaineer uses: Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of CLEAR informational meetings at each of our seven branches. on the cover: Sandeep Nain and Imran Rahman on the summit of Mount Rainier as part of an Asha for Education charity climb. -

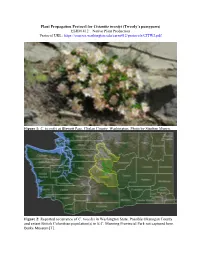

Draft Plant Propagation Protocol

Plant Propagation Protocol for Cistanthe tweedyi (Tweedy’s pussypaws) ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL: https://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/CITW2.pdf Figure 1: C. tweedyi at Blewett Pass, Chelan County, Washington. Photo by Stephen Munro. Figure 2: Reported occurrence of C. tweedyi in Washington State. Possible Okanogan County and extant British Columbian population(s) in E.C. Manning Provincial Park not captured here. Burke Museum [1]. Figure 3: USDA, 2018 [2]. TAXONOMY Plant Family Scientific Name Portulacaceae (Montiaceae is the new monophyletic family for this species) [3] Common Name Purslane family (Montia family) [3] Species Scientific Name Scientific Name Cistanthe tweedyi (A. Gray) Hershkovitz (not currently accepted) [3]. Varieties None Sub-species None Cultivar ‘Alba’, ‘Inshriach Strain’, ‘Rosea’[4], ‘Elliot’s Variety’ [5] Common Synonym(s) Calandrinia tweedyi A. Gray Lewisia aurantica A. Nels LETW Lewisia tweedyi (A. Gray) B.L. Rob. Lewisiopsis tweedyi (A.Gray) Govaerts (this most recently accepted designation placing the plant in a monotypic genus within family Montiaceae) [3] Oreobroma tweedyi Howell Common Name(s) Tweedy’s lewisia, Tweedy’s bitterroot, mountain rose Species Code (as per USDA Plants CITW2 database) GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range See Figure 2 for Washington State occurrences. In the United States C. tweedyi is known from the Wenatchee Mountains of Washington State chiefly in Chelan County and also occurring in northern portions of Kittitas County. The recorded occurrences of the species range from South Navarre Peak in north, south to near the town of Liberty, west to Ladies Pass and east to Twenty-Five Mile Creek [6]. It reportedly grows in the Methow Valley of Okanogan County, Washington yet, current reports neglect to record any Okanogan populations [1]. -

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report

OF~ 76-~ PETR)3ENFSIS OF THE MXJNT STUART BATHOLITH PID:rrnIC EQJI\7ALENT OF THE HIGH-AIJ.JMINA BASALT ASSO:IATION by Erik H. Erikson Jr. Depart:rrent of Geology Eastern Washington State College Cheney ,Wc::.shington 99004 June 1, 1976 Abstract. The 1-bunt Stuart batholith is a Late Cretaceous calc-alkaline pluton · . canposed of intrusive phases ranging in canposition fran two-pyroxene gabbro to granite. This batholith appears to represent the plutonic counterpart of the high-alumina basalt association. Mineralogical, petrological and chrono logical characteristics are consistent with a m:::rlel in which the intrusive series evolved fran one batch of magnesian high-alumina basalt by successive crystal fractionation of ascending residual magrna. ' canputer m:::rleling of this intrusive sequence provides a quanti- tative evaluation of the sequential change of magrna CCIIlfX)sition. These calculations indicate that this intrusive suite is consanguineous, and that subtraction of early-fonned crystals £ran the oldest magrna is capable of reprcducing the entire magrna series with a remainder of 2-3% granitic liquid. Increasing f()tash discrepancies prcduced by the rrodeling may reflect the increasing effects of volatile transfer in progressively rrore hydrous and silicic melts. Mass-balances between the arrounts of curn-ulate and residual liquid ccnpare favorably with the observed arrounts of intenrediate rocks exposed in the batholith, but not with the mafic rocks. Ma.fie cum: ulates must lie at depth. Mafic magmas probably fractionated by crystal settling, while quartz diorite and rrore granitic magrnas underwent a process of inward crystallization producing exposed gradationally zoned plutons.Aat present erosional levels. -

Wenatchee National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Wenatchee National Forest Pacific Northwest Region Annual Report on Wenatchee Land and Resource Management Plan Implementation and Monitoring for Fiscal Year 2003 Wenatchee National Forest FY 2003 Monitoring Report - Land and Resource Management Plan 1 I. INTRODUCTTION Purpose of the Monitoring Report General Information II. SUMMARY OF THE RECOMMENDED ACTIONS III. INDIVIDUAL MONITORING ITEMS RECREATION Facilities Management – Trails and Developed Recreation Recreation Use WILD AND SCENIC RIVERS Wild, Scenic And Recreational Rivers SCENERY MANAGEMENT Scenic Resource Objectives Stand Character Goals WILDERNESS Recreation Impacts on Wilderness Resources Cultural Resources (Heritage Resources) Cultural and Historic Site Protection Cultural and Historic Site Rehabilitation COOPERATION OF FOREST PROGRAMS with INDIAN TRIBES American Indians and their Culture Coordination and Communication of Forest Programs with Indian Tribes WILDLIFE Management Indicator Species -Primary Cavity Excavators Land Birds Riparian Dependent Wildlife Species Deer, Elk and Mountain Goat Habitat Threatened and Endangered Species: Northern Spotted Owl Bald Eagle (Threatened) Peregrine Falcon Grizzly Bear Gray Wolf (Endangered) Canada Lynx (Threatened) Survey and Manage Species: Chelan Mountainsnail WATERSHEDS AND AQUATIC HABITATS Aquatic Management Indicator Species (MIS) Populations Riparian Watershed Standard Implementation Monitoring Watershed and Aquatic Habitats Monitoring TIMBER and RELATED SILVICULTURAL ACTIVITIES Timer Sale Program Reforestation Timber Harvest Unit Size, Shape and Distribution Insect and Disease ROADS Road Management and Maintenance FIRE Wildfire Occurrence MINERALS Mine Site Reclamation Mine Operating Plans GENERAL MONITORING of STANDARDS and GUIDELINES General Standards and Guidelines IV. FOREST PLAN UPDATE Forest Plan Amendments List of Preparers Wenatchee National Forest FY 2003 Monitoring Report - Land and Resource Management Plan 2 I. -

April 2016 Report

Editor’s Note: Recreation Reports are printed every other week. April 26, 2016 Its spring, which means nice weather, wildflowers, bugs, fast flowing rivers and streams, and opening of national forest campgrounds. There are 137 highly developed campgrounds, six horse camps and 16 group sites available for use in the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. Opening these sites after the long winter season requires a bit more effort than just unlocking a gate. Before a campground can officially open for use the following steps need to occur: 1. Snow must be gone and campground roads need to be dry. 2. Hazard tree assessments occur. Over the winter trees may have fallen or may be leaning into other trees, or broken branches may be hanging up in limbs above camp spots. These hazards must be removed before it is safe for campers to use the campground. 3. Spring maintenance must occur. Crews have to fix anything that is broken or needs repair. That includes maintenance and repair work on gates, bathrooms/outhouses, picnic tables, barriers that need to be replaced or fixed, shelters, bulletin boards, etc. 4. Water systems need to be tested and repairs made, also water samples are sent to county health departments to be tested to ensure the water is safe for drinking. 5. Garbage dumpsters have to be delivered. 6. Once dumpsters are delivered, garbage that had been left/dumped in campgrounds over the winter needs to be removed. 7. Vault toilets have to be pumped out by a septic company. 8. Outhouses need to be cleaned and sanitized and supplies restocked. -

Water Powers of the Cascade Range

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ALBERT B. FALL, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 486 WATER POWERS OF THE CASCADE RANGE PART IV. WENATCHEE AND ENTIAT BAiMI&.rvey, "\ in. Cf\ Ci2k>J- *"^ L. PAEKEE A3TD LASLEY LEE I Prepared in cooperation with the WASHINGTOJS STATE BOARD OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Ernest Lister, Chairman Henry Landes, Geologist WASHINGTOH GOVBBNMBNT PBINTINJS OFFICE 1922 COPIE? ' .-.;:; i OF, THIS PUBLICATION MAT BE PBOCtJRED FE01C THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS ' 6OVEBNMENT PRINTING OF1JICB WASHINGTON, D. C. ' AT .80 CENTS PER,COPY n " '', : -. ' : 3, - .-. - , r-^ CONTENTS. Page. Introduction......i....................................................... 1 Abstract.................................................................. 3 Cooperation................................................ r,.... v.......... 4 Acknowledgments.............................. P ......................... 5 Natural features of Wenatcheeaad Entiat basins........................... 5 Topography................................... r ......................... 5 Wenatchee basin.........................I.........* *............... 5 Entiat basin............................................*........... 7 Drainage areas............................... i.......................... 7 Climate....................................i........................... 9 Control............................................................ 9 Precipitation.........^.................1......................... 9 Temperature...........................L........................ -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the CHELAN 30-MINUTE by 60-MINUTE QUADRANGLE, WASHINGTON by R

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-1661 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE CHELAN 30-MINUTE BY 60-MINUTE QUADRANGLE, WASHINGTON By R. W. Tabor, V. A. Frizzell, Jr., J. T. Whetten, R. B. Waitt, D. A. Swanson, G. R. Byerly, D. B. Booth, M. J. Hetherington, and R. E. Zartman INTRODUCTION Bedrock of the Chelan 1:100,000 quadrangle displays a long and varied geologic history (fig. 1). Pioneer geologic work in the quadrangle began with Bailey Willis (1887, 1903) and I. C. Russell (1893, 1900). A. C. Waters (1930, 1932, 1938) made the first definitive geologic studies in the area (fig. 2). He mapped and described the metamorphic rocks and the lavas of the Columbia River Basalt Group in the vicinity of Chelan as well as the arkoses within the Chiwaukum graben (fig. 1). B. M. Page (1939a, b) detailed much of the structure and petrology of the metamorphic and igneous rocks in the Chiwaukum Mountains, further described the arkoses, and, for the first time, defined the alpine glacial stages in the area. C. L. Willis (1950, 1953) was the first to recognize the Chiwaukum graben, one of the more significant structural features of the region. The pre-Tertiary schists and gneisses are continuous with rocks to the north included in the Skagit Metamorphic Suite of Misch (1966, p. 102-103). Peter Misch and his students established a framework of North Cascade metamorphic geology which underlies much of our construct, especially in the western part of the quadrangle. Our work began in 1975 and was essentially completed in 1980. -

HIKING Fall Is Prime Time to Hit NW Trails

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 • VOLUME 107 • NO. 5 MountaineerE X P L O R E • L E A R N • C O N S E R V E HIKING Fall is prime time to hit NW trails INSIDE: 2013-14 Course Guide, pg. 13 Foraging camp cuisine, pg. 19 Bear-y season, pg. 21 Larches aglow, pg. 27 inside Sept/Oct 2013 » Volume 107 » Number 5 13 2013-14 Course Guide Enriching the community by helping people Scope out your outdooor course load explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. 19 Trails are ripe with food in the fall Foraging recipes for berries and shrooms 19 21 Fall can be a bear-y time of year Autumn is often when hiker and bear share the trail 24 Our ‘Secret Rainier’ Part III A conifer heaven: Crystal Peak 27 Fall is the right time for larches Destinations for these hardy, showy trees 37 A jewel in the Olympics 21 The High Divide is a challenge and delight 8 CONSERVATION CURRENTS Makng a case for the Wild Olympics 10 OUTDOOR ED Teens raising the bar in oudoor adventure 28 GLOBAL ADVENTURES European resorts: winter panaceas 29 WEATHERWISE 37 Indicators point to an uneventful fall and winter 31 MEMBERSHIP MATTERS October Board of Directors Elections 32 BRANCHING OUT See what’s going on from branch to branch 46 LAST WORD Innovation the Mountaineer uses . DISCOVER THE MOUNTAINEERS If you are thinking of joining—or have joined and aren’t sure where to start—why not set a date to meet The Mountaineers? Check the Branching Out section of the magazine (page 32) for times and locations of informational meetings at each of our seven branches.