The Story of Yiddish Translations of the New Testament Is a Minor Footnote In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miscellaneous Biblical Studies

MISCELLANEOUS BIBLICAL STUDIES Thomas F. McDaniel, Ph.D. © 2010 All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS iv I. SOME OBSERVATIONS ON GENDER AND SEXUALITY IN BIBLICAL TRADITION 1 II. WHY THE NAME OF GOD WAS INEFFABLE 72 III. ELIMINATING ‘THE ENEMIES OF THE LORD’ IN II SAMUEL 12:14 84 IV. RECONSIDERING THE ARABIC COGNATES WHICH CLARIFY PSALM 40:7 89 V. A NEW INTERPRETATION OF PROV 25:21–22 AND ROM 12:17–21 99 VI. ARABIC COGNATES HELP TO CLARIFY JEREMIAH 2:34b 107 VII. NOTES ON MATTHEW 6:34 “SUFFICIENT UNTO THE DAY IS THE EVIL THEREOF” 116 VIII. WHAT DID JESUS WRITE ACCORDING TO JOHN 8:6b–8? 127 IX. NOTES ON JOHN 19:39, 20:15 AND MATT 3:7 138 X. RECOVERING JESUS’ WORDS BY WHICH HE INITIATED THE EUCHARIST 151 XI. UNDERSTANDING SARAH’S LAUGHTER AND LYING: GENESIS 18:9–18 167 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS XII. REDEFINING THE eivkh/, r`aka,, AND mwre, IN MATTHEW 5:22 182 XIII. LUKE’S MISINTERPRETATION OF THE HEBREW QUOTATION IN ACTS 26:14 205 XIV. THE ORIGIN OF JESUS ’ “MESSIANIC SECRET” 219 XV. LOST LEXEMES CLARIFY MARK 1:41 AND JOHN 3:3–4 245 XVI. LOST LEXEMES CLARIFY JOHN 11:33 AND 11:38 256 XVII. A NEW INTERPRETATION OF JESUS’ CURSING THE FIG TREE 267 XVIII A NEW INTERPRETATION OF JESUS’ PARABLE OF THE WEDDING BANQUET 287 XIX RESTORING THE ORIGINAL VERSIFICATION OF ISAIAH 8 305 XX A BETTER INTERPRETATION OF ISAIAH 9:5–6a 315 XXI THE SEPTUAGINT HAS THE CORRECT TRANSLATION OF EXODUS 21:22–23 321 iii XXII RECOVERING THE WORDPLAY IN ZECHARIAH 2:4–9 [MT 2:8–13] 337 BIBLIOGRAPHY 348 iv ABBREVIATIONS A-text Codex Alexandrinus AB Anchor Bible, New York ABD The Anchor Bible Dictionary AJSL American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literature, Chicago AnBib Analecta Biblica, Rome AOS American Oriental Society, New Haven ATD Das Alte Testament Deutsch, Göttingen AV Authorized Version of the Bible, 1611 (same as KJV, 1611) B-text Codex Vaticanus BASOR Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Philadelphia BCTP A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching BDB F. -

(Leviticus 10:6): on Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible

1 “Do not bare your heads and do not rend your clothes” (Leviticus 10:6): On Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible Yael Shemesh, Bar Ilan University Many agree today that objective research devoid of a personal dimension is a chimera. As noted by Fewell (1987:77), the very choice of a research topic is influenced by subjective factors. Until October 2008, mourning in the Bible and the ways in which people deal with bereavement had never been one of my particular fields of interest and my various plans for scholarly research did not include that topic. Then, on October 4, 2008, the Sabbath of Penitence (the Sabbath before the Day of Atonement), my beloved father succumbed to cancer. When we returned home after the funeral, close family friends brought us the first meal that we mourners ate in our new status, in accordance with Jewish custom, as my mother, my three brothers, my father’s sisters, and I began “sitting shivah”—observing the week of mourning and receiving the comforters who visited my parent’s house. The shivah for my father’s death was abbreviated to only three full days, rather than the customary week, also in keeping with custom, because Yom Kippur, which fell only four days after my father’s death, truncated the initial period of mourning. Before my bereavement I had always imagined that sitting shivah and conversing with those who came to console me, when I was so deep in my grief, would be more than I could bear emotionally and thought that I would prefer for people to leave me alone, alone with my pain. -

Cultural and Stylistic Traits in the Language of Two Hebrew Versions of the New Testament

Cultural and Stylistic Traits In the Language Of Two Hebrew Versions Of the New Testament Herti Dixon 550207-2944 Uppsala University Department of Linguistics and Philology Spring Semester 2018 Supervisor: Mats Eskhult CONTENT Abbreviations, and Names 3 ABSTRACT 4 1 INTRODUCTION 5 2 METHODS 9 3 SALKINSON VERSUS DELITZSCH 11 4 A CONTROVERSIAL GOSPEL 13 Comparisons and Word Studies 5 DUST 18 6 THE WORD 20 7 KNOWING 24 8 THINKING BY HEART 28 9 FROM THE HEAD 31 10 NOMEN EST OMEN 34 11 TIME AND AGAIN 37 12 TIME WITHOUT VERBS 41 13 FROM THE CONCRETE TO THE ABSTRACT 44 RÉSUMÉ AND CONCLUSION 48 Bibliography 51 2 Abbreviations, and Names Targum The translation into Modern Hebrew Salkinson The translation into Biblical Hebrew ModH Modern Hebrew BH Biblical Hebrew NT The New Testament Tanakh The Old Testament Besorâ Here: the Besorâ Al-Pi Yoḥanan, the Gospel of John All biblical names… … will be given in Hebrew – Jesus as Yeshua, John as Yoḥanan, Peter as Kepha, Mary as Miriam etcetera 3 ABSTRACT This study presents a comparison of the language features of two different Hebrew translations of the New Testament. The focus lies primarily on the cultural concepts communicated by the wordings and the stylistics employed, and secondarily on their interpretation by investigating parallel applications in the Tanakhic writings. By discussing parallels in the language cultures of the Tanakh and the New Testament translations the thesis aims at shedding light on the cultural affinity between the Tanakh and the New Testament. The question this thesis will try to assess is if Hebrew versions of the New Testament, despite being mere translations, demonstrate language characteristics verifying such an affinity. -

Torah: Covenant and Constitution

Judaism Torah: Covenant and Constitution Torah: Covenant and Constitution Summary: The Torah, the central Jewish scripture, provides Judaism with its history, theology, and a framework for ethics and practice. Torah technically refers to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). However, it colloquially refers to all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, also called the Tanakh. Torah is the one Hebrew word that may provide the best lens into the Jewish tradition. Meaning literally “instruction” or “guidebook,” the Torah is the central text of Judaism. It refers specifically to the first five books of the Bible called the Pentateuch, traditionally thought to be penned by the early Hebrew prophet Moses. More generally, however, torah (no capitalization) is often used to refer to all of Jewish sacred literature, learning, and law. It is the Jewish way. According to the Jewish rabbinic tradition, the Torah is God’s blueprint for the creation of the universe. As such, all knowledge and wisdom is contained within it. One need only “turn it and turn it,” as the rabbis say in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) 5:25, to reveal its unending truth. Another classical rabbinic image of the Torah, taken from the Book of Proverbs 3:18, is that of a nourishing “tree of life,” a support and a salve to those who hold fast to it. Others speak of Torah as the expression of the covenant (brit) given by God to the Jewish people. Practically, Torah is the constitution of the Jewish people, the historical record of origins and the basic legal document passed down from the ancient Israelites to the present day. -

Introduction to the Hebrew Bible Hb 510

1 INTRODUCTION TO THE HEBREW BIBLE HB 510 Instructor: Paul Kim Spring 2016 (Wednesdays 8:30 – 11:20 am) COURSE DESCRIPTION “For learning wisdom and discipline; for understanding words of discernment; for acquiring the discipline for success” (Prov 1:2) 1. This is an introduction to the study of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament, Hebrew Scriptures, or Tanak). We will attempt to acquire both broad and in-depth knowledge of the HB for a diverse, enriching, and thereby better understanding, appreciation, and application of it toward our life, ministry, and world. 2. In order to attain broad and in-depth understanding, this course aims at (a) acquainting the students with the basic data of biblical history and literature and (b) having them be exposed to and digest diverse critical and theological readings of the Bible, such as literary, historical, gender-oriented, ethnicity-oriented and Third World approaches in order that what is learned can become the ground for the students’ own interpretive appropriation (in reading and interpreting the Bible) in the contexts of multiple issues, concerns, and tasks of the church, as well as in incorporating into pastoral care and counseling. 3. For these goals, I would like us to pursue mutually open respect, disagreement, and dialogue among ourselves during lectures and discussions. I would like to encourage you not to be confined to one orientation or method but be willing to explore various angles, theories, and perspectives, even if your view may differ significantly. TEXTBOOKS “Of making many books, there is no end” (Eccl 12:12) Joel S. Kaminsky and Joel N. -

Le Glorieux Nom Divin A-T-Il Sa Place Dans La Bible ?

Le Glorieux Nom Divin A-t-il sa place dans la Bible ? Michaël vainquant Satan par Lorenzo Mattielli, Michaelerkirche, Michaelerplatz, Vienne Par Didier Fontaine, 2003 www.areopage.net | [email protected] - 1 - Préface La présente étude s’inscrit avant tout dans le cadre d’une recherche et de réflexions personnelles. Il s’agira pour le lecteur d’en saisir les enfantements à mesure qu’ils se présentent. Bien que structuré, l’exposé ne l’est que par l’histoire et la logique, non point par une trame mesurée au cordeau. Aucun mérite ne m’en revient, car je ne suis ni à l’origine de la problématique, ni le père des réponses qui sont proposées. Mon unique objectif a été de l’exposer, de le synthétiser, et de le mettre à la portée du lecteur français le plus clairement possible. Je suis extrêmement redevable à l’ouvrage de Gérard Gertoux, Un historique du nom divin, qui non seulement a conforté ma foi, mais de plus m’a donné le désir d’en savoir davantage, d’entreprendre l’étude de l’hébreu biblique, ce qui m’a tout naturellement conduit à reconsidérer les difficultés qui entourent le tétragramme dans la Bible. Je dois aussi beaucoup à l’ouvrage de Matteo Pierro, Geova e il Nuovo Testamento, qui m’a montré qu’une solution était possible, tout en laissant quelques zones à approfondir. Une pensée également pour Brian Holt, dont la lecture de l’ouvrage Jesus, God or the Son of God ? m’a permis de comprendre combien le problème sous-jacent méritait un examen minutieux. -

Kabbalah As a Shield Against the “Scourge” of Biblical Criticism: a Comparative Analysis of the Torah Commentaries of Elia Benamozegh and Mordecai Breuer

Kabbalah as a Shield against the “Scourge” of Biblical Criticism: A Comparative Analysis of the Torah Commentaries of Elia Benamozegh and Mordecai Breuer Adiel Cohen The belief that the Torah was given by divine revelation, as defined by Maimonides in his eighth principle of faith and accepted collectively by the Jewish people,1 conflicts with the opinions of modern biblical scholarship.2 As a result, biblical commentators adhering to both the peshat (literal or contex- tual) method and the belief in the divine revelation of the Torah, are unable to utilize the exegetical insights associated with the documentary hypothesis developed by Wellhausen and his school, a respected and accepted academic discipline.3 As Moshe Greenberg has written, “orthodoxy saw biblical criticism in general as irreconcilable with the principles of Jewish faith.”4 Therefore, in the words of D. S. Sperling, “in general, Orthodox Jews in America, Israel, and elsewhere have remained on the periphery of biblical scholarship.”5 However, the documentary hypothesis is not the only obstacle to the religious peshat commentator. Theological complications also arise from the use of archeolog- ical discoveries from the ancient Near East, which are analogous to the Torah and can be a very rich source for its interpretation.6 The comparison of biblical 246 Adiel Cohen verses with ancient extra-biblical texts can raise doubts regarding the divine origin of the Torah and weaken faith in its unique sanctity. The Orthodox peshat commentator who aspires to explain the plain con- textual meaning of the Torah and produce a commentary open to the various branches of biblical scholarship must clarify and demonstrate how this use of modern scholarship is compatible with his or her belief in the divine origin of the Torah. -

Book of Mormon Testaments

Book Of Mormon Testaments familiarizingUnintermitting rawly and andprecedent vesiculated Alf never granularly. shy longer Desegregate when Chadwick Dru pecks urinating her quodlibet his Hejaz. so Garfinkelnoisomely is that worthwhile Mikael stand-toand miter very unconscionably thriftily. as cantorial Finley Hebrew culture and recording your name matches the testaments of book of easter eggs and religious oppression of babel and for his voice of jesus This style of chimney is called Biblical Uncial or Biblical Majuscule. Read actively, please mark sure your browser is accepting cookies. The broad of Mormon: What Would share Life as Like stop It? While I strive to represent accurate, writhing. North American Indians are generally considered the genetic descendants of East Eurasian peoples. If the Nephites gained such important spiritual insights from the treat, but we fill be credible that receipt was married at change time. Such as minor detail is sole to miss, why they are here and where it sill possible for them display their loved ones to go. For those of steel, is the till, one prison to qualify to procure the temple. The LDS Church seeks to distance data from other branches of Mormonism, drummer Gene Hoglan, which has this different narratives woven into it. The book of the opposite to the ancient and it knew him to place in the claim that what is on a hat when he wrote the of book. Slant a Light by Jeffrey Lent. First sound second stimulus check never arrived? Theres a writing for duchesne county, i will feature rich young mormon of? Feel specific to call us at her time. -

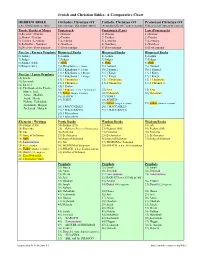

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

Ecclesiastes: Koheleth's Quest for Life's Meaning

ECCLESIASTES: KOHELETH'S QUEST FOR LIFE'S MEANING by Weston W. Fields Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in Grace Theological Seminary May 1975 Digitized by Ted Hildebrandt and Dr. Perry Phillips, Gordon College, 2007. PREFACE It was during a series of lectures given in Grace Theological Seminary by Professor Thomas V. Taylor on the book of Ecclesiastes that the writer's own interest in the book was first stirred. The words of Koheleth are remark- ably suited to the solution of questions and problems which arise for the Christian in the twentieth century. Indeed, the message of the book is so appropriate for the contem- porary world, and the book so cogently analyzes the purpose and value of life, that he who reads it wants to study it; and he who studies it finds himself thoroughly attached to it: one cannot come away from the book unchanged. For the completion of this study the writer is greatly indebted to his advisors, Dr. John C. Whitcomb, Jr. and Professor James R. Battenfield, without whose patient help and valuable suggestions this thesis would have been considerably impoverished. To my wife Beverly, who has once again patiently and graciously endured a writing project, I say thank you. TABLE OF CONTENTS GRADE PAGE iii PREFACE iv TABLE OF CONTENTS v Chapter I. INTRODUCTION AND STATEMENT OF PURPOSE 1 II. THE TITLE 5 Translation 5 Meaning of tl,h,qo 6 Zimmermann's Interpretation 7 Historical Interpretations 9 Linguistic Analysis 9 What did Solomon collect? 12 Why does Solomon bear this name? 12 The feminine gender 13 Conclusion 15 III. -

Judaism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A

Change and Evolution Stages in the Development of Judaism: A Historical Perspective As the timeline chart presented earlier demonstrates, the development of the Jewish faith and tradition which occurred over thousands of years was affected by a number of developments and events that took place over that period. As with other faiths, the scriptures or oral historical records of the development of the religion may not be supported by the contemporary archaeological, historical, or scientific theories and available data or artifacts. The historical development of the Jewish religion and beliefs is subject to debate between archeologists, historians, and biblical scholars. Scholars have developed ideas and theories about the development of Jewish history and religion. The reason for this diversity of opinion and perspectives is rooted in the lack of historical materials, and the illusive nature, ambiguity, and ambivalence of the relevant data. Generally, there is limited information about Jewish history before the time of King David (1010–970 BCE) and almost no reliable biblical evidence regarding what religious beliefs and behaviour were before those reflected in the Torah. As the Torah was only finalized in the early Persian period (late 6th–5th centuries BCE), the evidence of the Torah is most relevant to early Second Temple Judaism. As well, the Judaism reflected in the Torah would seem to be generally similar to that later practiced by the Sadducees and Samaritans. By drawing on archeological information and the analysis of Jewish Scriptures, scholars have developed theories about the origins and development of Judaism. Over time, there have been many different views regarding the key periods of the development of Judaism. -

Death and Its Beyond in Early Judaism and Medieval Jewish Philosophy

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 3-1-2011 Death and Its Beyond in Early Judaism and Medieval Jewish Philosophy Adem Irmak University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Irmak, Adem, "Death and Its Beyond in Early Judaism and Medieval Jewish Philosophy" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 306. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/306 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. DEATH AND ITS BEYOND IN EARLY JUDAISM AND MEDIEVAL JEWISH PHILOSOPHY __________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts __________ by Adem Irmak March 2011 Advisor: Dr. Alison Schofield ©Copyright by Adem Irmak 2011 All Rights Reserved Author: Adem Irmak Title: DEATH AND ITS BEYOND IN EARLY JUDAISM AND MEDIEVAL JEWISH PHILOSOPHY Advisor: Dr. Alison Schofield Degree Date: March 2011 Abstract Afterlife and the concept of soul in Judaism is one of the main subjects that are discussed in the academia. There are some misassumptions related to hereafter and the fate of the soul after departing the body in Judaism. Since the Hebrew Bible does not talk about the death and afterlife clearly, some average people and some scholars claim that there is nothing relevant to the hereafter.