AIUK 13 (Mount Stewart, County Down)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

18_121726-bindex.qxp 4/17/09 2:59 PM Page 486 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Ardnagashel Estate, 171 Bank of Ireland The Ards Peninsula, 420 Dublin, 48–49 Abbey (Dublin), 74 Arigna Mining Experience, Galway, 271 Abbeyfield Equestrian and 305–306 Bantry, 227–229 Outdoor Activity Centre Armagh City, 391–394 Bantry House and Garden, 229 (Kildare), 106 Armagh Observatory, 394 Barna Golf Club, 272 Accommodations. See also Armagh Planetarium, 394 Barracka Books & CAZ Worker’s Accommodations Index Armagh’s Public Library, 391 Co-op (Cork City), 209–210 saving money on, 472–476 Ar mBréacha-The House of Beach Bar (Aughris), 333 Achill Archaeological Field Storytelling (Wexford), Beaghmore Stone Circles, 446 School, 323 128–129 The Beara Peninsula, 230–231 Achill Island, 320, 321–323 The arts, 8–9 Beara Way, 230 Adare, 255–256 Ashdoonan Falls, 351 Beech Hedge Maze, 94 Adrigole Arts, 231 Ashford Castle (Cong), 312–313 Belfast, 359–395 Aer Lingus, 15 Ashford House, 97 accommodations, 362–368 Agadhoe, 185 A Store is Born (Dublin), 72 active pursuits, 384 Aillwee Cave, 248 Athlone, 293–299 brief description of, 4 Aircoach, 16 Athlone Castle, 296 gay and lesbian scene, 390 Airfield Trust (Dublin), 62 Athy, 102–104 getting around, 362 Air travel, 461–468 Athy Heritage Centre, 104 history of, 360–361 Albert Memorial Clock Tower Atlantic Coast Holiday Homes layout of, 361 (Belfast), 377 (Westport), 314 nightlife, 386–390 Allihies, 230 Aughnanure Castle (near the other side of, 381–384 All That Glitters (Thomastown), -

254 the Belfast Gazette, 31St July, 1964 Inland Revenue

254 THE BELFAST GAZETTE, 31ST JULY, 1964 townlands of Castlereagh and Lisnabreeny in the Armagh County Council, 1, Charlemont Place, County of Down (hereinafter referred to as "the Armagh. Castlereagh substation"). Down County Council, Courthouse, Downpatrick. 2. A double circuit 275 kV tower line from the Co. Down. 275/110 kV transforming substation to be estab- Belfast County Borough Council, City Hall, Bel- lished at Tandragee under the No. 11 Scheme, fast, 1. 1962, to the Castlereagh substation via the north Antrim Rural District Council, The Steeple, side of Banbridge, the south east side of Dromore Antrim. and the west side of Carryduff. Banbridge Rural District Council, Linenhall Street, 3. A double circuit 275 kV tower line from the Banbridge, Co. Down. 275/110 kV transforming substation within the Castlereagh Rural District Council, 368 Cregagh boundaries of the power station to be established Road, Belfast, 6. at Ballylumford, Co. Antrim, under the No. 12 Hillsborough Rural District Council, Hillsborough, Scheme, 1963, to the Castlereagh substation via Co. Down. the west side of Islandmagee, the north side of Larne Rural District Council, Prince's Gardens, Ballycarry, the south east side of S'traid, the east Larne, Co. Antrim. side of Hyde Park, the east and south east sides Lisburn Rural District Council, Harmony Hill, of Divis Mountain, the west side of Milltown and Lisburn, Co. Antrim. the south side of Ballyaghlis. Tandragee Rural District Council, Linenhall 4. Two double circuit 110 kV lines from the Castle- Street, Banbridge, Co. Down. reagh substation to connect with points on the existing double circuit 110 kV line between the Electricity Board for Northern Ireland, Danes- Finaghy and Rosebank 110/33 kV transforming fort, 120 Malone Road, Belfast, 9. -

Irland Zählt Zu Den Schönsten Reisezielen Europas

Irland zählt zu den schönsten Reisezielen Europas. Scheinbar immergrüne Landschaften wechseln sich mit den kargen Felsformationen im BurrenGebiet und der reizvollen ConnemaraRegion ab. Die Rei Irland se führt auch immer wieder an den „Wild Atlantic Way“ und damit zu den spektakulärsten Küstenab schnitten des Landes: dem Ring of Kerry, den Cliffs of Moher und dem Giant´s Causeway. Die „Grüne Wiesen, Klippen, Pints und Kreuze: Insel“ ist gleichermaßen ein Hort der Kultur. Ein „Mile failte“ auf der Grünen Insel langes keltischchristliches Erbe prägte Land und Leute und spiegelt sich in zahllosen, jahrhunderte alten Ausgrabungen, Kirchen und Klosterruinen im ganzen Land wider. Ein besonderer Höhepunkt der Reise ist außerdem der Besuch des Titanic Museums in Belfast, in dem Sie nicht nur mehr über das wohl bekannteste Schiff der Welt, sondern auch über die Menschen und das Leben in dieser Zeit, erfahren! Highlights Reizvolle Städte Belfast, Galway und Cork Unterwegs am Wild Atlantic Way: Irlands schönste Küsten Ulster: Facettenreiches Nordirland Rock of Cashel Irland 12 Tag 4 Letterkenny – Sligo – Connemara – Galway Teils der Strecke des „Wild Atlantic Ways“ folgend, führt unsere Rei se durch Donegal, den wildromantischen Nordwesten Irlands. Über Sligo gelangen wir zum Küstenort Westport an der Clew Bay. Hier ragt der 753 m hohe Croagh Patrick, der „heilige Berg Irlands“, un vermittelt und weithin sichtbar aus dem Küstenvorland auf. Die Fahrt durch die Region Connemara zeigt uns eine kontrastreiche und ur sprünglich anmutende Landschaft, die von Seen, Mooren, Felsen, tief eingeschnittenen Buchten und kahlen Bergkegeln geprägt wird. In weiten Teilen nur sehr dünn besiedelt, wirkt die Connemara bis weilen wie ein mystisches Naturparadies. -

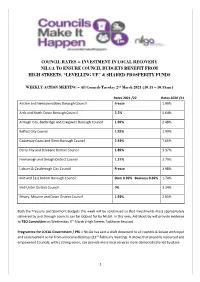

Action Points from NILGA OB Meeting 2Nd March 2021

COUNCIL RATES = INVESTMENT IN LOCAL RECOVERY NILGA TO ENSURE COUNCIL BUDGETS BENEFIT FROM HIGH STREETS, “LEVELLING UP” & SHARED PROSPERITY FUNDS WEEKLY ACTION MEETING – All Councils Tuesday 2nd March 2021 (10.15 – 10.55am) Rates 2021 /22 Rates 2020 /21 Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council Freeze 1.99% Ards and North Down Borough Council 2.2% 5.64% Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council 1.99% 2.48% Belfast City Council 1.92% 1.99% Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council 2.49% 7.65% Derry City and Strabane District Council 1.89% 3.37% Fermanagh and Omagh District Council 1.37% 2.79% Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council Freeze 3.98% Mid and East Antrim Borough Council Dom 0.99% Business 0.69% 1.74% Mid Ulster District Council 0% 3.24% Newry, Mourne and Down District Council 1.59% 2.85% Both the Treasury and Stormont Budgets this week will be scrutinised so that investments most appropriately delivered by and through councils can be lobbied for by NILGA. In this vein, Ald Moutray will provide evidence to TEO Committee on Wednesday 3rd March (High Streets Taskforce Session). Programme for LOCAL Government / PfG – NILGA has sent a draft document to all councils & Solace with input and endorsement so far from all local authorities (22nd February meeting). It shows that properly resourced and empowered Councils, with a strong vision, can provide more local services more democratically led by place. 1 Economy - In May 2021, NILGA Full Members will be invited to an event to look at the new economic environment and councils’ roles in driving enterprise locally. -

Cottage Ornee

Survey Report No. 30 Janna McDonald and June Welsh Cottage Ornée Mount Stewart Demesne County Down 2 © Ulster Archaeological Society First published 2016 Ulster Archaeological Society c/o School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology The Queen’s University of Belfast Belfast BT7 1NN Cover illustration: Artist’s impression of the Cottage Ornée at Mount Stewart, County Down. J. Magill _____________________________________________________________________ 3 CONTENTS List of figures 4 1. Summary 5 2. Introduction 9 3. Survey 15 4. Discussion 17 5. Recommendations for further work 29 6. Bibliography 29 Appendix Photographic record 30 4 LIST OF FIGURES Figures Page 1. Location map for Mount Stewart.......................................................................... 5 2. View of monument, looking west……….............................................................6 3. Mound, looking south-east....................................................................................7 4. The Glen Burn, to the south of the site, looking east………................................7 5. Quarry face to the north-west, looking south………………………....................8 6. View of the north wall, looking south-east…………............................................9 7. Photogrammetry image of north wall....................................................................9 8. Mount Stewart house and gardens……................................................................11 9. Estate map (Geddes 1779)…………………………............................................11 10. OS -

Councillor B Hanve

Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council Dr. Theresa Donaldson Chief Executive Island Civic Centre, The Island, Lisburn, BT27 4RL Tel: 028 9250 9451 Email: [email protected] www.lisburncity.gov.uk www.castlereagh.gov.uk Island Civic Centre The Island LISBURN BT27 4RL 26 March 2015 Chairman: Councillor B Hanvey Vice-Chairman: Councillor T Mitchell Councillors: Councillor N Anderson, Councillor J Baird, Councillor B Bloomfield, Councillor P Catney, A Givan, Councillor J Gray, Alderman T Jeffers, Councillor A McIntyre, Councillor T Morrow, Councillor J Palmer, Councillor L Poots, Alderman S Porter, Councillor R Walker Ex Officio Presiding Member, Councillor T Beckett Deputy Presiding Member, Councillor A Redpath The monthly meeting of the Environmental Services Committee will be held in the Chestnut Room, Island Civic Centre, The Island, Lisburn, on Wednesday, 1 April 2015, at 5.30 pm, for the transaction of business on the undernoted agenda. Please note that hot food will be available prior to the meeting from 5.00 pm. You are requested to attend. DR THERESA DONALDSON Chief Executive Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council Agenda 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Minutes of the Environmental Services Committee meeting held on 11 March 2015 4. Report from Director of Environmental Services 1. Sub-Regional Animal Welfare Arrangements 2. Rivers Agency – Presentation on Flood Maps on Northern Ireland 3. Bee Safe 4. Dog Fouling Blitz 5. Service Delivery for the Environmental Health Service 6. Relocation of the Garage from Prince Regent Road 7. Adoption of Streets under the Private Streets (NI) Order 1980 as amended by the Private Streets (Amendment) (NI) Order 1992 8. -

Comber Historical Society

The Story Of COMBER by Norman Nevin Written in about 1984 This edition printed 2008 0 P 1/3 INDEX P 3 FOREWORD P 4 THE STORY OF COMBER - WHENCE CAME THE NAME Rivers, Mills, Dams. P 5 IN THE BEGINNING Formation of the land, The Ice Age and after. P 6 THE FIRST PEOPLE Evidence of Nomadic people, Flint Axe Heads, etc. / Mid Stone Age. P 7 THE NEOLITHIC AGE (New Stone Age) The first farmers, Megalithic Tombs, (see P79 photo of Bronze Age Axes) P 8 THE BRONZE AGE Pottery and Bronze finds. (See P79 photo of Bronze axes) P 9 THE IRON AGE AND THE CELTS Scrabo Hill-Fort P 10 THE COMING OF CHRISTIANITY TO COMBER Monastery built on “Plain of Elom” - connection with R.C. Church. P 11 THE IRISH MONASTERY The story of St. Columbanus and the workings of a monastery. P 12 THE AUGUSTINIAN MONASTERY - THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY, THE NORMAN ENGLISH, JOHN de COURCY 1177 AD COMBER ABBEY BUILT P13/14 THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY IN COMBER The site / The use of river water/ The layout / The decay and plundering/ Burnt by O’Neill. P 15/17 THE COMING OF THE SCOTS Hamiltons and Montgomerys and Con O’Neill-The Hamiltons, 1606-1679 P18 / 19 THE EARL OF CLANBRASSIL THE END OF THE HAMILTONS P20/21 SIR HUGH MONTGOMERY THE MONTGOMERIES - The building of church in Comber Square, The building of “New Comber”. The layout of Comber starts, Cornmill. Mount Alexander Castle built, P22 THE TROUBLES OF THE SIXTEEN...FORTIES Presbyterian Minister appointed to Comber 1645 - Cromwell in Ireland. -

Belfast MIPIM 2020 Delegation Programme

Delegation Programme Tuesday 10th March 09:00 Belfast Stand 10:00 - 10:45 Belfast Stand 11:00 – 11:45 Belfast Stand 12:00 - 14:00 Belfast Stand Opens Belfast Potential: Perfectly Positioned Belfast: City of Innovation - Investor Lunch Where Ideas Become Reality Tea, Coffee & Pastries Suzanne Wylie, Chief Executive, Belfast City Council By Invitation Only Speakers Scott Rutherford, Director of Research and Enterprise, Queen’s University Belfast Thomas Osha, Senior Vice President, Innovation & Economic Development, Wexford Science & Technology Petr Suska, Chief Economist and Head of Urban Economy Innovation, Fraunhofer Innovation Network Chair Suzanne Wylie, Chief Executive, Belfast City Council 14:15 – 14:55 Belfast Stand 15:00 – 15:45 Belfast Stand 16:00 Belfast Stand 18:00 Belfast Stand Sectoral focus on film and Our Waterfront Future: Keynote with Belfast Stand Closes Belfast Stand Reopens creative industries in Belfast Wayne Hemingway & Panel Discussion On-stand Networking Speakers Speakers James Eyre, Commercial Director, Titanic Quarter Wayne Hemingway, Founder, HemingwayDesign Joe O’Neill, Chief Executive, Belfast Harbour Scott Wilson, Development Director, Belfast Harbour Nick Smith, Consultant, Belfast Harbour Film Studios James Eyre, Commercial Director, Titanic Quarter Tony Wood, Chief Executive, Buccaneer Media Cathy Reynolds, Director of City Development and Regeneration, Belfast City Council Chair Stephen Reid, Chief Executive, Ards and North Down Borough Nicola Lyons, Production Manager, Northern Ireland Screen Council Chair -

The Private Gardens of Dublin

The Irish Rover A Tour Around Ireland’s Finest Gardens Two departures available: June 25 – July 2, 2015 (depart USA on June 24) August 13 – 20, 2015 (depart USA on August 12) This tour is arranged in collaboration between Hidden Treasures Tours and Brightwater Holidays of Scotland. Hidden Treasures Tours has collaborated with Brightwater Holidays on all UK tour since 2007. The tour leader will be a botanical expert that leads this tour annually for Brightwater Holidays. A tour in Ireland promises a rich feast of horticultural excellence, with memorable and beguiling gardens, enthusiastic and skilful owners and an ever-changing backdrop of lush green hills, fertile fields and glittering seascapes. Our north to south journey is packed full of gems yet relaxed and unhurried, taking in the very best that the Emerald Isle has to offer. We begin in Northern Ireland on the shores of Strangford Lough, whose sub-tropical micro-climate lends itself particularly well to the creation of lush and exotic gardens. Nowhere is this more evident than at the dazzling and idiosyncratic garden of Mount Stewart, truly one of the great gardens of the world. We also visit romantic Rowallane and atmospheric Castle Ward. We move on to Dublin where we meet June Blake, a passionate plantswoman who grows a unique mix of bamboos, ornamental grasses and perennials. The unmissable Dillon Garden features of course, along with Hunting Brook, with its fusion of prairie and tropical planting; Killruddery, a historic garden that still retains much of its original 17th century style; the Italianate seaside garden at Corke Lodge and Powerscourt, one of Ireland’s most famous gardens with magnificent vistas over the surrounding countryside. -

Ulster-Scots

Ulster-Scots Biographies 2 Contents 1 Introduction The ‘founding fathers’ of the Ulster-Scots Sir Hugh Montgomery (1560-1636) 2 Sir James Hamilton (1559-1644) Major landowning families The Colvilles 3 The Stewarts The Blackwoods The Montgomerys Lady Elizabeth Montgomery 4 Hugh Montgomery, 2nd Viscount Sir James Montgomery of Rosemount Lady Jean Alexander/Montgomery William Montgomery of Rosemount Notable individuals and families Patrick Montgomery 5 The Shaws The Coopers James Traill David Boyd The Ross family Bishops and ministers Robert Blair 6 Robert Cunningham Robert Echlin James Hamilton Henry Leslie John Livingstone David McGill John MacLellan 7 Researching your Ulster-Scots roots www.northdowntourism.com www.visitstrangfordlough.co.uk This publication sets out biographies of some of the part. Anyone interested in researching their roots in 3 most prominent individuals in the early Ulster-Scots the region may refer to the short guide included at story of the Ards and north Down. It is not intended to section 7. The guide is also available to download at be a comprehensive record of all those who played a northdowntourism.com and visitstrangfordlough.co.uk Contents Montgomery A2 Estate boundaries McLellan Anderson approximate. Austin Dunlop Kyle Blackwood McDowell Kyle Kennedy Hamilton Wilson McMillin Hamilton Stevenson Murray Aicken A2 Belfast Road Adams Ross Pollock Hamilton Cunningham Nesbit Reynolds Stevenson Stennors Allen Harper Bayly Kennedy HAMILTON Hamilton WatsonBangor to A21 Boyd Montgomery Frazer Gibson Moore Cunningham -

Absenteeism in Northern Ireland Councils 2008-09

Absenteeism in Northern Ireland Councils 2008-09 REPORT BY THE CHIEF LOCAL GOVERNMENT AUDITOR 11 December 2009 This report has been prepared under Article 26 of the Local Government (Northern Ireland) Order 2005. John Buchanan Chief Local Government Auditor December 2009 The Department of the Environment may, with the consent of the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland, designate members of Northern Ireland Audit Office staff as local government auditors.The Department may also, with the consent of the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland, designate a local government auditor as Chief Local Government Auditor. The Chief Local Government Auditor has statutory authority to undertake comparative and other studies designed to enable him to make recommendations for improving economy, efficiency and effectiveness in the provision of services by local government bodies and to publish his results and recommendations. For further information about the work of local government auditors within the Northern Ireland Audit Office please contact: Northern Ireland Audit Office 106 University Street BELFAST BT7 1EU Telephone:028 9025 1100 Email: [email protected] Website: www.niauditoffice.gov.uk © Northern Ireland Audit Office 2009 Contents Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 Scope of the report 4 Main findings 5 REPORT 9 Absenteeism within councils 10 Absenteeism for the sector as a whole 19 Causes of absence in councils 28 Absenteeism policies in councils 32 Absenteeism targets in councils 34 Absenteeism data in councils -

HI15 Pass Word Template

10 BIRR CASTLE GARDENS 33 GIANT’S CAUSEWAY 56 POWERSCOURT GARDENS AND SCIENCE CENTRE VISITOR EXPERIENCE €2 OFF ADULT GARDEN ADMISSION 10% OFF ADMISSION NOT VALID FOR CASTLE TOURS 34 GLASNEVIN CEMETERY MUSEUM 57 ROS TAPESTRY 11 BLARNEY CASTLE & GARDENS 20% DISCOUNT ON COMBINED MUSEUM & TOUR TICKET 20% OFF ADMISSION 10% DISCOUNT WITH ONE FULL PAYING ADULT 35 THE GUILDHALL 58 RUSSBOROUGH 12 BOYNE VALLEY FREE ADMISSION TWO FOR ONE 13 BUNRATTY CASTLE & FOLK PARK 36 GUINNESS STOREHOUSE 59 SAINT PATRICK’S CATHEDRAL 10% OFF ADMISSION & 10% DISCOUNT ON SHOP 10% OFF ADMISSION €1 OFF ADULT ADMISSION PURCHASES 37 HOUSE OF WATERFORD CRYSTAL 60 SHANNON FERRIES 14 THE BURREN CENTRE & TWO FOR ONE 10% OFF WITH ONLINE BOOKINGS THE KILFENORA CÉILÍ BAND PARLOUR 38 IRISH NATIONAL STUD & GARDENS 61 SKIBBEREEN HERITAGE CENTRE 20% OFF ADMISSION TWO FOR ONE 20% OFF EXHIBITION 15 BUTLERS CHOCOLATE EXPERIENCE 39 THE JACKIE CLARKE COLLECTION 62 SMITHWICK’S EXPERIENCE KILKENNY SPECIAL OFFER Includes free 100g Butlers Chocolate bar FREE ADMISSION 10% OFF ADULT ADMISSION 16 CAHERCONNELL STONE FORT 40 JEANIE JOHNSTON TALL SHIP & 63 STROKESTOWN PARK And Sheep Dog Demonstrations EMIGRANT MUSEUM TWO FOR ONE 10% OFF ADMISSION Adult Admission 20% OFF ADMISSION 64 THOMOND PARK STADIUM 17 CASINO MARINO 41 JOHNNIE FOX’S PUB TWO FOR ONE 18 CASTLETOWN HOUSE 10% DISCOUNT ON HOOLEY NIGHT 65 TITANIC BELFAST 19 CLARE MUSEUM 42 THE KENNEDY HOMESTEAD & 10% OFF ADMISSION FREE ADMISSION EMIGRANT TRAIL 66 TOWER MUSEUM 10% OFF ADMISSION 20 THE CLIFFS OF MOHER TWO FOR ONE 43 2015 VISITOR EXPERIENCE KILBEGGAN DISTILLERY EXPERIENCE 67 TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN TWO FOR ONE ON ADULT ADMISSION AND SELF-GUIDED SPECIAL OFFER 10% DISCOUNT IN THE CLIFFS VIEW CAFÉ 10% OFF PURCHASES OF €50 OR MORE IN THE LIBRARY SHOP TOURS ONLY 21 COBH HERITAGE CENTRE 68 TULLAMORE D.E.W.